The real estate crisis that began with the collapse of China’s largest developer Evergrande has taken an unusual and potentially calamitous turn. During the past week, homebuyers in over 230 projects—most unfinished—in some 86 cities are engaging in a “mortgage boycott”, refusing to make any further payments on unfinished pre-sold homes where construction is stalled due to developer funding issues.

In the past week, buyers of more than 230 properties in 86 cities have joined together to collectively refuse to make mortgage payments for unfinished, pre-sold units unless construction resumes, according to real-time updates on software development platform Github under the “WeNeedHome” project.

This collective action on the part of frustrated homebuyers exposes China’s banking system to fresh strains as unpaid mortgages fall into default.

It exposes more financial weakness and is set to affect already-shaken confidence in the system, according to independent economist Hong Hao.

“Banks will have to write down loans, affecting their capital sufficiency and lending ability, at a time when bank lending is most needed to sustain growth,” said Hong.

Could Not Come At A Worse Time

As I noted earlier in the week, China’s economy is already feeling the strain of its loose money and looser credit policies, both geared towards stimulating an economy that is already starting to contract.

With total social financing having nearly doubled in the past month, rising defaults at China’s banks threaten to put a strain on their liquidity at a time when they can least afford it.

A growing local banking crisis in Henan province, where depositors at several local and regional banks have been unable to withdraw any of their funds for over two months is compounding the problem—making it significant enough for China’s banking regulators to feel compelled to issue a number of statements designed to offer up reassurances that Beijing has matters well in hand.

Zhao Qingming, a veteran financial economist, told the Global Times on Thursday cases like the Henan village banks' default show that financial risks often break out in a concentrated way in certain regions, but they are unlikely to extend into large-scale systematic risks.

"The loan provision rate by domestic large and medium banks, mostly above 150 percent and sometimes even 300 or 400 percent, are generally enough to cover non-performing loans or other risks," Zhao said.

Bringing The Property Bond Defaults Onshore

However, risks seem to be growing, with yet another large developer, Shimao Group, defaulting on a dollar bond interest payment.

Shanghai-based Shimao Group failed to pay the interest and principal on a $1 billion bond due Sunday, according to a company filing to the Hong Kong stock exchange. The bond had no grace period for the principal, according to its offering document.

The lack of a grace period for the principal means Shimao Group went immediately into formal default on that bond issuance, adding to the growing list of “offshore” defaults on bonds sold to overseas investors outside of China.

For the most part, the financial fallout from China’s collapsing property bubble has been concentrated among overseas investors. 2022 has been remarkable in that most corporate bond defaults in China have been among its portfolio of offshore bonds.

However, that disparity appears to be largely the result of onshore bondholders having relatively fewer recourse options and thus are more compelled to give developers more flexibility in meeting bond and debt repayment obligations.

…the onshore calm is mostly the result of borrowers’ ability to force debt reprieves such as repayment delays and debt swaps on creditors who face a less efficient legal system to protect their interests. Many local bondholders find themselves trapped in a cycle of seemingly endless maturity extensions with little room to negotiate, partly as authorities encourage such compromises so as to preserve social and economic stability.

That flexibility may now be reaching its limits. Evergrande—”patient zero” in China’s property bubble collapse—is facing a potential onshore default, as local creditors have rejected an extension request on an onshore bond repayment.

Holders of a puttable yuan-denominated bond from the firm’s main onshore unit Hengda Real Estate Group Co. rejected a plan to further extend payment past a July 8 deadline by six months, according to a Shenzhen stock exchange filing Monday. The company had held a meeting last week to seek creditor approval, but more than 90% of the voting holders rejected the proposed extension.

Hengda said in a reply to a Bloomberg News query that it’s still actively seeking to talk with holders of the yuan bond. The creditors’ rejection of a proposed extension to the bond payment period won’t affect Hengda’s operations and risk disposal, the company said. The firm added that its operations have been improving recently, and said it will step up efforts in homebuilding and delivery to support the bond repayment.

It is against this backdrop of rising risk of onshore defaults that China’s “mortgage boycott” crisis has appeared, and could threaten to squeeze Chinese banks and creditors from both ends, as developers and homeowners alike default on an increasing amount of property-related debt.

Focusing On China’s Weak Local Banking Regulations

The growing “mortgage boycott” is coming on the heels as well of a local banking crisis in Henan province, where several local “village” banks have been summarily shuttered—leaving depositors unable to access their funds for months.

For months, rural savers have taken to the streets in Zhengzhou, Henan province, to demand their money after finding that their deposits had been frozen since April 18 at four banks – Yuzhou Xinminsheng Village Bank, Shangcai Huimin County Bank, Zhecheng Huanghuai Community Bank and New Oriental Country Bank of Kaifeng.

The protests subsequently escalated to a violent clash on Sunday. Protesters were surrounded by local police and were recorded being beaten by unidentified men in white shirts.

While the exact mis-steps and mistakes of the affected banks remains unclear, what seems unmistakable is that the crisis arose in part because of lax regulatory enforcement by local banking regulators—at least, that is the prevailing narrative.

Relevant regulatory authorities have evidently been asleep at the switch when it comes to oversight of village banks in Henan, Dong Ximiao, chief researcher at the Zhongguancun Internet Finance Institute, told the Global Times on Thursday.

It seems that the sporadic occurrence of risk incidents involving Henan village banks over recent years, albeit many of these cases isolated to specific localities, hasn't prompted local regulatory authorities into sufficient and timely actions to address the loopholes in the first place until the recent incidents draw public attention, Dong said.

Given that China’s “village banks” make up approximately 36% of all banking institutions in China, and carry some 29% of all banking assets in China, any expansion of the Henan crisis to other village banks, or a rise in loan defaults that precipitate liquidity and funding crises at these same banks, would add significant stress to China’s overall banking and credit system. The banks are already posing a growing challenge to China’s banking regulatory systems.

A Perfect Storm Of Crises?

While the mortgage boycott and Henan’s village bank crisis are notionally small events focused on the smallest of China’s banks, their coincidental timing also overlaps with a raft of poor economic news for China overall:

The average price of newly built homes in China declined by 0.5% Year-on-Year, the second straight month of declines, which itself was the culmination of a steady slowing of price growth extending back over a year.

Industrial capacity utilization declined during the second quarter, the weakest performance since the second quarter of 2020, just as China was emerging from its first series of lockdowns.

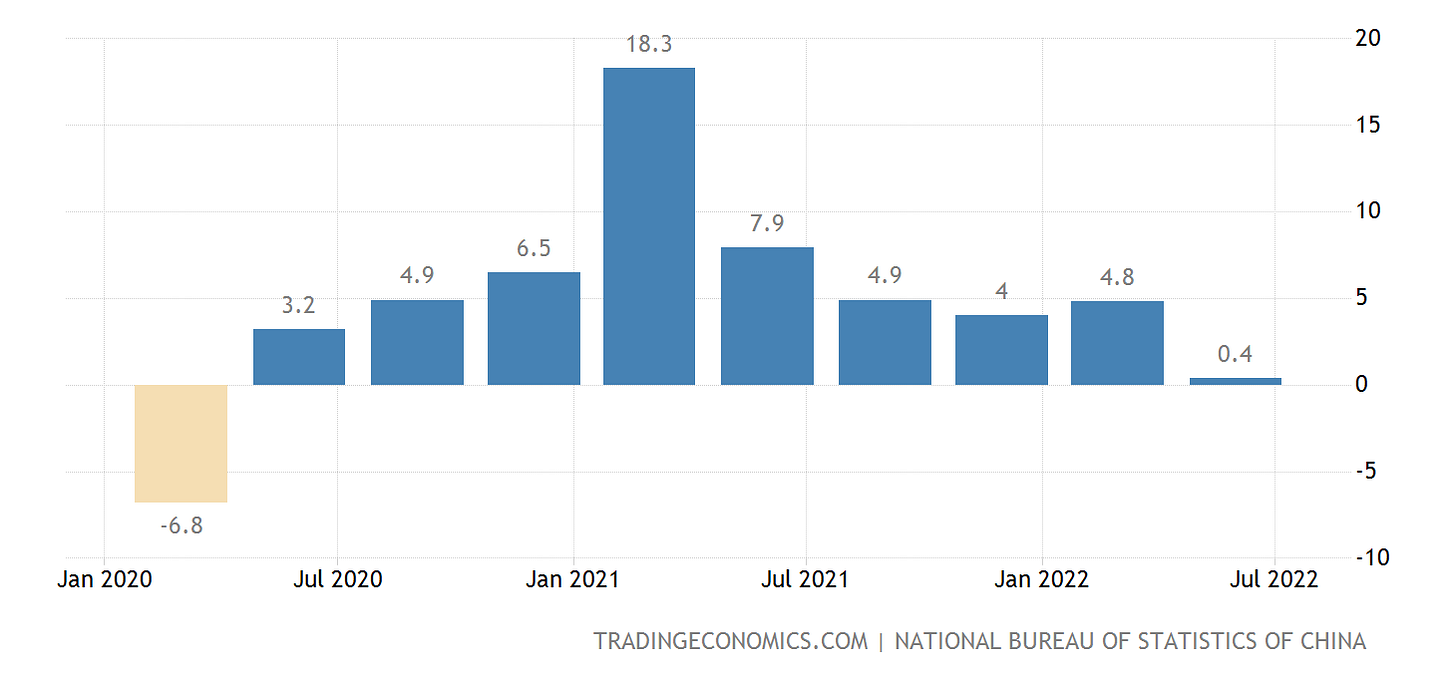

China’s annual GDP growth rate was just 0.4% during the second quarter, the weakest performance since the first quarter of 2020, when much of the country was in lockdown.

During the second quarter, China’s GDP actually contracted by 2.6%, the first quarterly decline since that first quarter of 2020.

It is worth noting that these contractions occurred even as China successively doubled total social financing and credit throughout the quarter—an epic failure of monetary stimulus.

Will the mortgage boycott metastasize into a broader onshore banking crisis in China? It is far too soon to answer that question with anything besides speculation.

However, the growing mortgage boycott highlights the extent of both the economic and societal impacts being felt from the collapse of China’s real-estate sector. The failure of developers to complete housing projects at all (let alone on time) is leaving many Chinese homebuyers without the properties they indebted themselves to acquire. Not only does this inspire movements such as the mortgage boycott, which can in turn impact the banks which are the holders of those debt instruments, but the rising discontent among the Chinese people threatens to upend China’s vaunted political and societal stabilities—just months before the Chinese Community Party’s 20th Congress, at which President Xi Jinping is widely expected to secure an unprecedented 3rd term in office.

China’s mortgage boycotts and village bank defaults are tiny reminders that the structural financial flaws laid bare by Evergrande’s collapse have not been resolved and are steadily getting worse, not better. China’s real estate bubble continues to deflate, and it has a long way to go before it has collapsed fully. Whether China will still have a functioning economy or a stable polity at the end of that process is very much an open question.

"financial risks often break out in a concentrated way in certain regions, but they are unlikely to extend into large-scale systematic risks."

So the crisis has been "contained", eh? -- LOL