Is China Moving Ahead In Global Race To The Bottom?

Spike In Loan Growth Does Little To Improve Economic Picture In The Middle Kingdom

The global nature of the current recession was underscored this past week by China’s deteriorating economy. Proving that even centrally planned and managed economies are not immune to inflation, China’s inflation rate rose to 2.5%, the highest level since July of 2020.

Inflation Distorting China’s Economic Outlook

While a 2.5% inflation rate looks small next to the levels being experienced here in the US and elsewhere, it is still more than double the inflation rate in July of 2021, and nearly three times the inflation rate logged just this past January.

In China, as elsewhere, the true impacts of inflation are less in its overall level and more in the distorting effect it has on prices throughout the economy. June marked the third consecutive month food price inflation rose, and at 2.9% is the highest it has been since September of 2020. Given China’s recent history of food price disinflation, the reversal into inflation is a significant and most unwelcome turnaround.

At the same time, China’s core inflation rate has been much more steady, hovering between 0.9% and 1.3% since early last year.

Inflation The Old Fashioned Way—By Printing Money

The cause of China’s rapidly rising inflation is not hard to divine, as it coincides with an equally rapid expansion of bank lending, which came in well above forecasts and expectations.

Banks extended CNY 2.8 trillion in new yuan loans in June. Economists had forecast lending to rise to CNY 2.4 trillion from CNY 1.89 trillion in May.

Total social financing, a broad measure of credit and liquidity in the economy, rose to CNY 5.2 trillion from CNY 2.8 trillion, data showed.

Total social financing, a measure of credit and liquidity, almost doubled from May.

The rise in lending is of a piece with China’s looser monetary policies, resulting in China’s M1 money supply expanding in June by nearly 3 CNY trillion.

Monetary Stimulus Used To Inflate A Shrinking Economy

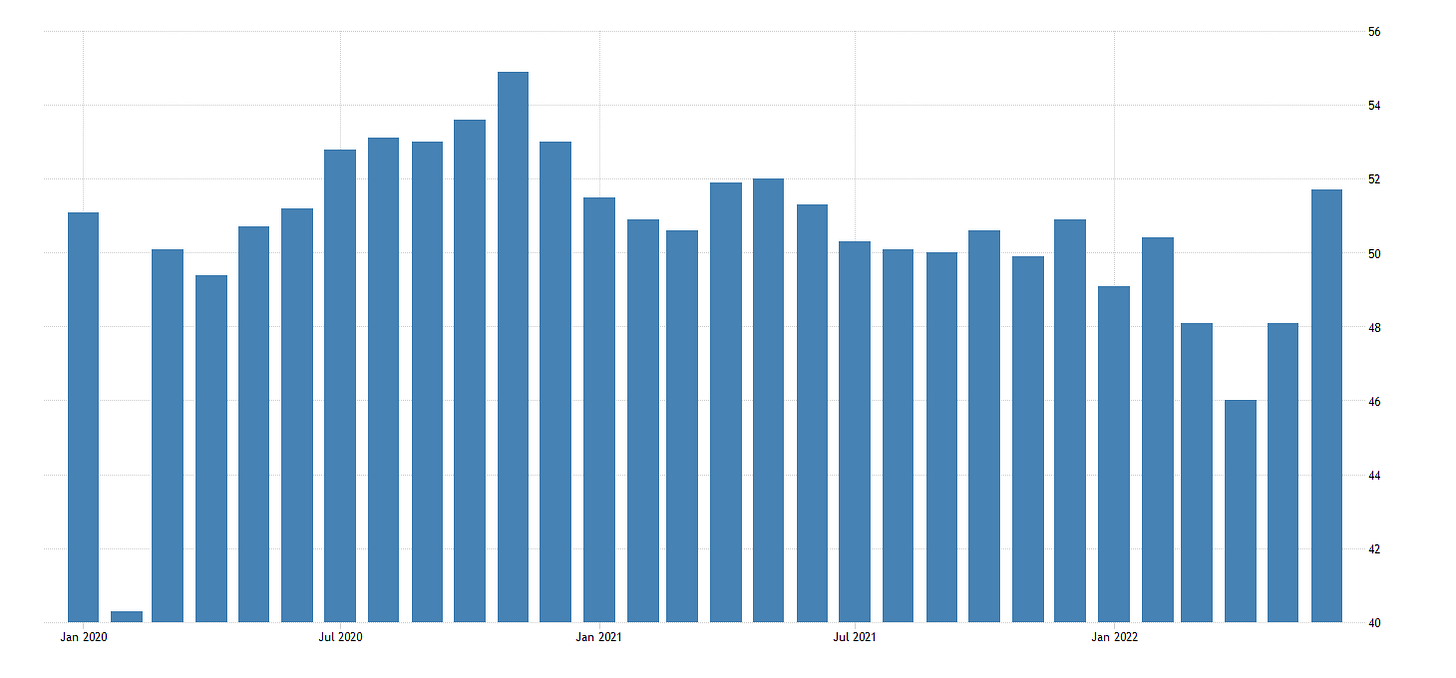

The goal of China’s recent bouts of monetary stimulus has been simple: to re-inflate a contracting economy. Arguably, there has been some modest success, as June saw both the services and manufacturing PMI figures, as well as the composite number, climb back above 50 (expansion). However, that success has been uneven, as the manufacturing number improvement was somewhat muted, rising only to 51.70.

That success is even further diluted by recent reverses on the Chinese stock markets, which saw over two months of steady gains peter out by the beginning of July, as the markets began surrendering much of those gains.

Nor has the monetary stimulus conferred any advantage over the US, as the yuan and the dollar continue their recent sideways dance on forex markets.

While the official GDP numbers are not due out until Friday, a Bloomberg survey of economists are projecting a slowing annual GDP growth rate for the second quarter, and possibly even a quarterly contraction in GDP.

The economy’s performance in the second quarter was likely the weakest since an historic contraction in the first three months of 2020 when the pandemic first hit. Economists predict GDP likely grew 1.2% in the second quarter from a year ago, down from 4.8% in the first three months of the year. On a quarterly basis, GDP likely shrank 2%.

Far from bringing about robust economic growth, China’s increases in private sector loans, in total social financing, and in the overall money supply have at best delayed further economic contraction. There is not a lot of bang to show for the newly created Chinese bucks.

Stimulus Or No Stimulus, Zero COVID Means Zero Growth

A major factor in China’s lukewarm results from its monetary stimulus efforts has been the ongoing fear of fresh COVID-19 lockdowns, as successive variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus manage to return home to China, including the rather more infectious BA.5.

On Monday, local government officials in the city of Shanghai deemed 37 streets to be at medium risk of COVID-19 transmission and one street designated high risk. While city officials have yet to impose an official lockdown, the classification means residents would not be allowed to leave their homes as part of the city’s efforts to curb the spread of the virus, the report said.

The Shanghai government will also conduct PCR tests for all residents living in nine of the city’s 16 districts, according to a statement posted on the social media app WeChat as first reported by the Washington Post.

While Shanghai has yet to announce formal lockdown measures, officials in the city of Wugang, in Henan province, have already announced a 3-day lockdown, confining the city’s 320,000 inhabitants to their homes, with official authorizations needed any travel of any kind.

None of the city's 320,000 people are allowed to set foot outside their homes until midday Thursday, the notice said, adding that basic necessities would be delivered by local authorities.

Residents are not allowed to use their cars without permission and must obtain official authorisation to travel under "closed-loop" conditions in case of emergencies, the notice said.

The city of Zhumadian also announced similar measures for its 7 million residents, although its restrictions are milder.

The lingering effects of the prior “Zero COVID” lockdowns as well as fears of future lockdowns is negating much of Beijing’s efforts at stimulus, with the result that China is almost certain to not be able to achieve the 5.5% growth objective for the economy set by the Chinese Politburo.

Like swatting flies with a shovel, China’s Covid strategy can be effective, but also costly and contentious. It entails locking down apartment blocks, neighborhoods or even whole cities for days or weeks to stamp out even handfuls of cases. As a result, Mr. Xi’s insistence on Covid zero, or “dynamic zero” as Beijing calls it, has cast an unsettling shadow over the country’s economic expectations.

The Chinese government is scheduled to release the main economic data for this year’s second quarter on Friday. According to a survey by Bloomberg, economists expect that the Chinese government will report that gross domestic product grew about 1 percent in the second quarter, compared with a year earlier. That’s a big comedown from the 4.8 percent expansion in the first quarter, and is likely to put the government’s 5.5 percent growth goal for all of this year out of reach.

The one constant in China’s evolving economic outlook: “Zero COVID” still means zero growth.

The Limits Of Stimulus

China’s recent uneven economic performance is another sobering reminder that, even in the most totalitarian of regimes, a government’s ability to influence the economy through stimulus measures remains limited. Merely printing money, or encouraging more loans and generating more private credit and liquidity, only go so far in generating fresh business activity. The CCP can compel the Chinese people to do a great deal, but ordering the economy to grow is proving to be somewhat beyond their capacity; eventually the stimulus measures generate economic toxins such as inflation that overwhelm whatever positive effects are produced.

While the Federal Reserve’s recent pivot to tighter monetary policy carries with it significant societal costs in terms of job loss, unemployment, and suppression of consumer demand (i.e., “demand destruction”), China shows that the alternatives are hardly any better, and are potentially even worse.

If China’s GDP results come in anywhere close to what has been forecast, despite their looser monetary policy, China’s economy is still edging ahead in the global economic race to the bottom. Loose money and stimulus measures do not appear to be winning against persistent forces of contraction (especially fears of more government-ordered lockdowns). With the global economy entering recession, all such government interventions appear destined to ultimately fail.

How can you stimulate an economy, with stimulus, if no one is allowed out of their houses? Do they really buy everything online?