The price of oil is too low.

With Brent Crude currently sitting some 27% above its January, 2019 price range, and West Texas Intermediate sitting 37% above its January, 2019, price range, readers may quite reasonably believe I have lost what little sanity I ever possessed. And I may have!

In this bit of madness there is a bit of method, however, and that method is this: oil prices are failing to measure up to repeated projections of demand growth. The anticipated demand for oil keeps failing to materialize.

Why might that be?

We begin by considering the demand forecasts from the beginning of this year, such as the International Energy Agency’s forecast from its January Oil Market Report:

Global oil demand is set to rise by 1.9 mb/d in 2023, to a record 101.7 mb/d, with nearly half the gain from China following the lifting of its Covid restrictions. Jet fuel remains the largest source of growth, up 840 kb/d. OECD oil demand slumped by 900 kb/d in 4Q22 as weak industrial activity and weather effects lowered use, while non-OECD demand was 500 kb/d higher.

This forecast marked a belief that oil demand would return to the levels of growth recorded during 2021, when total world demand for oil rose by nearly 7mb/d.

The IEA also anticipated that the majority of this demand growth would come from Asia—and from China in particular.

The preeminent driver of 2023 GDP and oil demand growth will be the timing and pace of China’s post-lockdown recovery – a variable surrounded by even more uncertainty than usual following December’s sudden policy U-turn. However, China’s persistently dim macro-economic outlook, characterised by rising unemployment, a slump in factory output and a deepening property crisis

precludes a bigger upward revision.

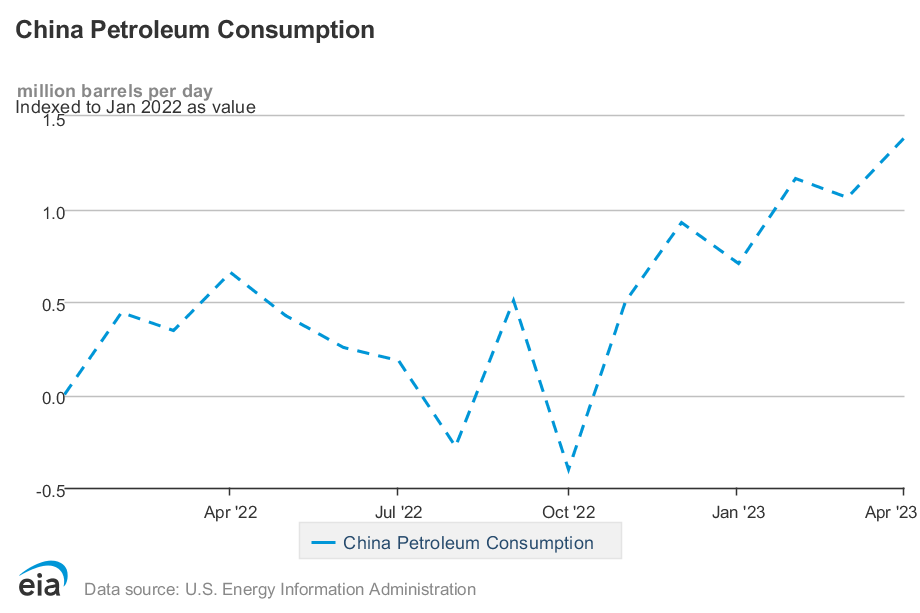

Even the US Energy Information Agency forecast significant growth in China’s energy demand.

World demand growth has been forecast by the EIA as being largely powered by China’s demand growth.

With total world oil consumption for all of 2023 forecast to be 1.9% of January 2023 models, even just a straight linear trend in growth should have resulted in Brent Crude being priced at around $81.74/bbl, and West Texas Intermediate should have been priced at around $77.37/bbl.

As of yesterday’s close, Brent Crude is priced at $76.61/bbl, and West Texas Intermediate is priced at $72.73/bbl.

What happened? Why is the price of oil not rising in line with demand growth forecasts?

The most obvious part of the answer is that oil production has kept pace with demand. While global oil demand had been forecast at 101.72 million bbl/d at the end of 2022, global oil production was not far off the pace at 100.7 million bbl/d, and actual demand came in below production at 99.9 million bbl/d.

Where there is rising production, rising demand is not going to exert upward price pressure.

However, contrary to the forecasts from January, we also have not been seeing rising demand. According to IEA estimates, total world oil demand peaked in the third quarter of 2022 at 100.7 million bbl/d, and dropped to 99.6 million bbl/d for the first quarter of 2023—a demand decline of over 1 million barrels per day.

Against the backdrop of actual demand the OPEC+ production cuts at the beginning of April are confirmed to be the defensive manuever I assessed them to be at the time.

While the corporate media hyperfocused on the narrative that the Saudi decision was a plus for Putin and Russia while being a negative everywhere else, and that this must be due to waning US influence in the Middle East, the reality is likely far more mundane: the OPEC+ nations need to produce less oil if they want to see higher prices per barrel. The production cut is more about a growing glut in oil than it is any geopolitical power game between Saudi Arabia, Russia, and the United States.

Oil demand fell by more than a million barrels per day during the first quarter of 2023. In response OPEC+ announced production cuts of more than a million barrels per day. On the surface this would be a reasonable response in order to support the price of oil.

Only it has failed to do even that.

When Saudi Arabia announced the production cuts on April 2nd, Brent Crude was priced at around $79.47/bbl, and West Texas Intermediate was priced around $75.57/bbl. Even factoring in last week’s recovery in oil prices, Brent Crude and WTI are both approximately $3/bbl below the price in place immediately prior to the production cut announcement.

If market price is the market’s assessment of current and future demand, the oil markets are not exactly optimistic about oil demand as we move through the second quarter of 2023.

Nor is it just the price of oil that is telling us that demand has been weaker than forecast. Saudi Arabia’s oil revenues also lead to that conclusion.

Oil revenues fell by 3% to 179 billion riyals in the first three months of the year on lower crude prices.

This fall in oil revenue was sufficient for the Saudi government to run a rare deficit of 2.91 billion riyals ($770 million) for the first quarter of 2023.

Moreover, China’s industrial statistics, as I have noted several times previously at this point, have been weaker than anticipated.

The Caixin Manufacturing PMI in China fell into contraction territory during April, dropping to 49.5 from 50 in March, continuing a long-term downward trend from its post-pandemic peak in the fall of 2020.

This was confirmed by China’s National Bureau of Statistics, which calculated the manufacturing PMI for China in April at 49.2. Again, the April 2023 mark was a continuation of a downward trend since late 2020.

Even the non-manufacturing PMI from the NBS showed a marked downturn in April, even though in March it had reached a post-pandemic high.

Even electricity production, although up, showed only an incremental gain over March output in previous years.

This is hardly the economic “reopening” that many had anticipated in December at the end of the Zero COVID protocols. Even the financial analysis site Motley Fool noted how China had so far underperformed market expectations.

Western companies were no doubt licking their lips as Beijing began to drop its stringent zero-covid policies late last year. But five months into 2023, and it's clear the post-pandemic era's sleeping giant is still hitting the snooze button.

It takes no great skill with economics or finance to see that if China’s growth is needed to power the bulk of world economic growth, and China’s growth is proving to be problematic, then world economic growth—and world oil demand by implication—will also be problematic.

Strangely enough, despite the lackluster economic performance of China thus far in 2023, and despite the weakening prices of oil, a good many economists are still forecasting Brent Crude will reach $90/bbl or even $100/bbl by the end of this year.

An April survey of economists and analysts by Reuters showed strong consensus on Brent Crude achieving an average price of $87.12/bbl for the year.

Oil prices will pick up pace towards $90 a barrel over the course of this year as production cuts by OPEC+ and rebounding China demand shield against a deteriorating economic backdrop in the West, a Reuters poll showed on Friday.

A survey of 40 economists and analysts forecast Brent crude would average $87.12 a barrel in 2023, up from the $86.49 consensus in March and current levels of around $78. The global benchmark has averaged around $82 per barrel so far this year.

For its part, Goldman Sachs continues to push its forecast of $100/bbl by April of next year.

Despite the sharp declines experienced by oil prices in recent weeks, Goldman Sachs (NYSE:GS) reiterated its forecast for Brent prices at $95 dollars by December 2023 and at $100 for April 2024.

Supply deficits are expected to surge in the second half of the year, the firm predicts.

Even the IEA is anticipating that world oil demand will rise to 100.8 million bbl/d during this second quarter of 2023, and rise another 2 million bbl/d during the third quarter.

While such increases in demand are always possible, the market prices are not reflecting such increased levels of demand at the present time, and the longer oil prices remain below the average forecast for the year, the higher oil prices will have to rise during the latter portion of the year in order for the average price estimates to hold true.

The hill oil has to climb to keep the forecasts is getting steeper, not shallower.

That oil demand is getting tangled up in central bank interest rate hikes shows just how steep that hill is getting.

Crude oil and gasoline prices Thursday settled mixed, with crude falling to a 5-month low. A stronger dollar Thursday weighed on energy prices. Crude oil prices also fell on concern that the ongoing U.S. banking turmoil and the Fed's rate hikes will slow the economy and energy demand. The Fed raised interest rates by 25 bp Wednesday, and the ECB raised rates by +25 bp Thursday and signaled more rate increases are coming. Crude prices rebounded from their worst levels on signs of strength in Chinese fuel demand.

The fear that continued rate hikes by either the Fed or the ECB will further depress the global economy are fairly widespread, despite the desires of Goldman Sachs, et al, to think optimistically about Chinese and global oil demand.

That Russian Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Novak is working the media trying to jawbone oil prices up also shows how steep that hill is getting.

Oil has been slumping due to concerns about the economy as U.S. politicians discuss ways to avoid a debt default, and investors anticipate more rate hikes globally. Prices were also affected by U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen's statement that the government could run out of money within a month, the ongoing contraction in the manufacturing sector, and signs of emerging cracks in the labor market. Additionally, concerns about diesel demand and weakening prospects from the world's two largest economies, China and the U.S., contributed to the decline in oil prices.

Yet the optimism persists, despite its growing irrationality. Research firm Wood Mackenzie in late March was still clinging to a growth model for oil demand that had China alone supplying 40% of the global demand.

“A return to normal mobility in China is the single biggest demand driver, accounting for 1.0 million barrels per day (b/d) of the 2.6 million b/d increase this year,” a team of analysts led by vice president Massimo Di Odoardo said in the report, laying out its base case scenario. That means 38.5% of global oil demand recovery would come from China.

In part this forecast rests on the presumption that China’s reopened economy will grow 7% in 2023, even though Wood Mackenzie believes China will achieve that level of growth through infrastructure spending.

In its high-growth scenario, the firm expects Chinese officials will turn to measures to stimulate the economy by boosting infrastructure spending, which it forecasts will raise construction growth by more than 10% in 2023.

Yet what is being ignored in such an assessment is that stimulus measures are applied when “normal” economic growth is found wanting. Thus, if China does follow through with a raft of government stimulus projects, it will not be because the economy is doing well but because the economy is doing poorly. Stimulus spending by Beijing means China’s economy is at best barely growing and at worst significantly weakening, which makes the 7% GDP growth estimate not just optimistic but extravagantly so.

As much as the financial press frets about a “possible” recession sometime in 2023, the reality of the data continues to be that the recession is here and is getting deeper. The reality of oil markets is that they are reacting to the global economy’s weakness, not its ever-hope-for strength.

The reality of oil prices is that they are a bellwether for where the global economy is headed—and where the global economy is currently headed is down and not up. The reality of oil prices is that, for the global economy to be heading up any time soon, oil prices are far too low.

"I could stand $1.68 a gallon and a mean tweet."

-John Rich

Thanks Peter - another article meeting the timely what's top of our minds topics! How does our US govt use of (or need to replinish) our oil reserves (is there a law or mandate about how and when we replinish?) Play here?