These Signals Aren't Just Mixed. They're Completely Scrambled.

The Surrealism Is Not Yet Done

The past 10 days have been “chaotic” in banking and finance, to put it mildly.

The madness began with the surprise liquidation of Silvergate Capital:

Crypto-focused lender Silvergate said it is winding down operations and will liquidate the bank after being financially pummeled by turmoil in digital assets.

“In light of recent industry and regulatory developments, Silvergate believes that an orderly wind down of Bank operations and a voluntary liquidation of the Bank is the best path forward,” it said in a statement Wednesday.

The bank’s plan includes “full repayment of all deposits,” it said.

It quickly reached a zenith with the equally surprising seizure of Silicon Valley Bank by California state regulators and the FDIC.

Silicon Valley Bank has been seized by financial regulators after a run on deposits tipped the bank into collapse, in the largest US bank failure since the Great Recession in 2008.

California state regulators shuttered the bank on Friday, and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) immediately took control of the bank's $209 billion in assets and $175.4 billion in deposits.

The bank based in Santa Clara, California had been the 18th largest bank in the US, and primarily catered to the tech startups and wealthy entrepreneurs of Silicon Valley.

By comparison, the seizure of Signature Bank of New York was almost an afterthought.

We are also announcing a similar systemic risk exception for Signature Bank, New York, New York, which was closed today by its state chartering authority. All depositors of this institution will be made whole. As with the resolution of Silicon Valley Bank, no losses will be borne by the taxpayer.

In the space of five days, the leading “crypto bank” closed its doors for good while the FDIC processed the second and third largest bank failures in US history.

With three significant bank failures in rapid succession, one can almost forgive the corporate media for throwing around words like “contagion” and fretting that the entire banking system is on the precipice.

Shares of U.S. regional banks slumped on Monday, led by sharp losses in First Republic Bank as news of fresh financing failed to assuage fears of possible bank contagion following the collapse of SVB Financial Group and Signature Bank.

San Francisco-based First Republic has been able to meet withdrawal demands with the help of additional funding from JPMorgan Chase, the mid-cap lender’s executive chair, Jim Herbert, told CNBC.

His reassurance did little to keep the stock afloat. There were multiple trading halts as shares tumbled, last down 67% at $28.05.

Even tech-centric Wired indulged in some apocalyptic hyperventilation.

The second- and third-order impacts of startups hitting financial trouble or just slowing down could be more pernicious. “When you say: ‘Oh, I don’t care about Silicon Valley,’ yes, that might sound fine. But the reality is very few of us are Luddites,” Kunst says. “Imagine you wake up and go to unlock your door, and because they’re a tech company banking with SVB who can no longer make payroll, your app isn’t working and you’re struggling to unlock your door.” Perhaps you try a rideshare company or want to hop on a pay-by-the-hour electric scooter, but can’t because their payment system is provided by an SVB client who now can’t operate.

Yes, the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank was presumably the first in a chain of events culminating in the collapse of the Internet and civilization as we know it.

Or…not.

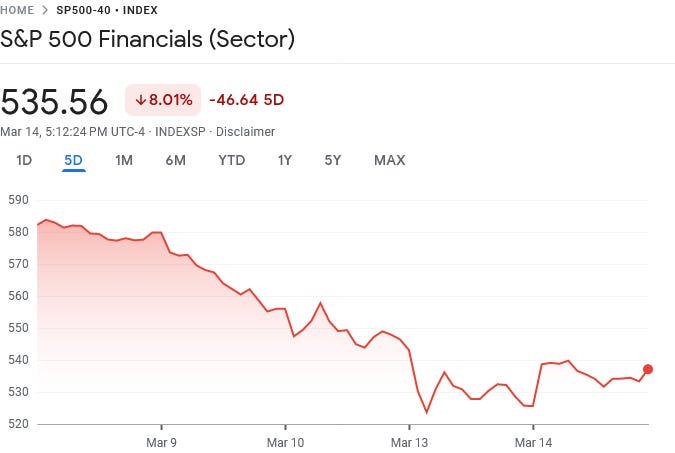

While Monday (March 13) was a stock market bloodbath, just one trading day later saw a stabilization and even recovery in the S&P 500 Financials Index.

Even the S&P 500 Banks Index did better.

By the end of trading on Monday, most bank run fears had subsided, and by yesterday even the regional banks which had led the markets down just 24 hours earlier were leading the markets back up again.

Shares of regional banks posted big gains on Tuesday as they regained their footing after huge losses in the previous session, but volatility continued in the sector following the demise of Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank and Silvergate Capital in the past week.

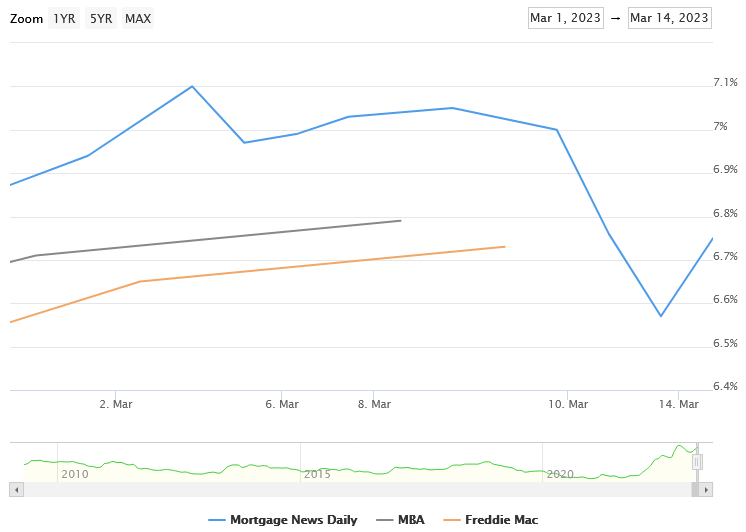

Even mortgage rates, which had plunged on Friday and again on Monday recovered somewhat, with the 30-Year mortgage rising to 6.75%.

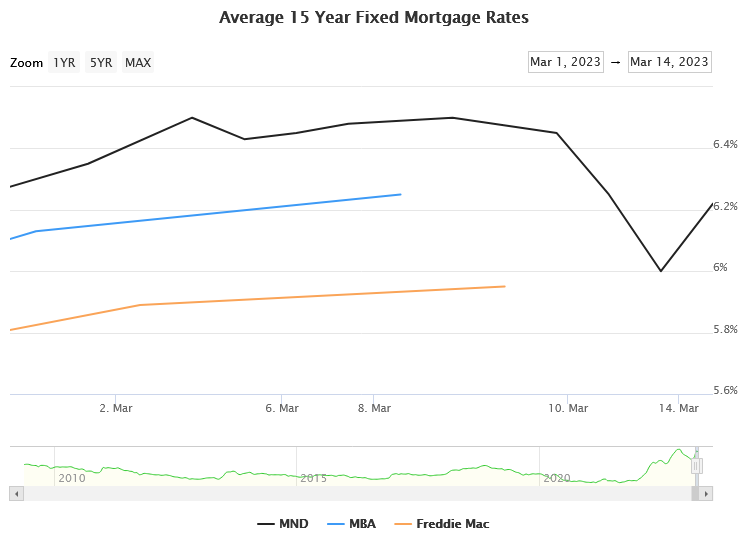

For its part the 15-Year mortgage recovered by a similar relative margin.

Adding to Tuesday’s good news was the Bureau of Labor Statistics releasing the Consumer Price Index Summary for February, showing that consumer price inflation had retreated.

The Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U) rose 0.4 percent in February on a seasonally adjusted basis, after increasing 0.5 percent in January, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today. Over the last 12 months, the all items index increased 6.0 percent before seasonal adjustment.

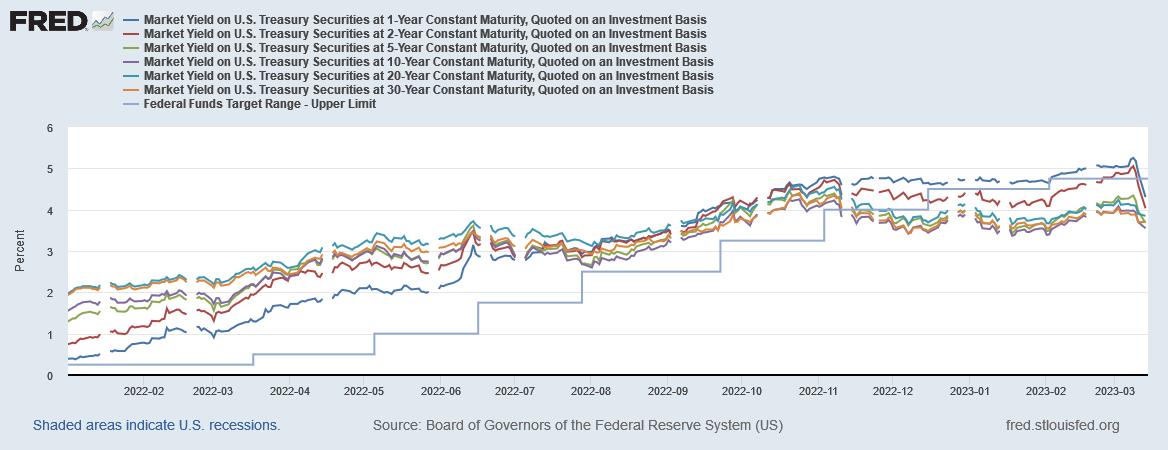

However, not everything rebounded and more or less reversed Monday’s losses. Treasury yields in particular failed to recover much, although the 2-Year Treasury, 5-Year Treasury, and 10-Year Treasury all at least stabilized.

Even though yields did not drop dramatically on Tuesday, by the end of the day yields remained between half a percentage point and a full percentage point lower than when the market hysterics began. The market panic of the past several days has made a complete wreck of the Fed’s interest rate hikes, with yields stabilizing where they were in the middle of last September, when the Federal Funds rate was a 150 bps lower than it is now.

As dramatic as the tectonic shifts in the financial terrain have been, it is far too soon to know with any degree of confidence what the practical impacts of these shifts will be—although there are no end of commentators in both the alternative and corporate media pontificating about exactly those practical impacts.

The Wall Street Journal saw a crisis in banking confidence arising from the inevitable decline in fair market values from legacy assets from before the Fed started hiking rates.

But the failures culminated in liquidity crunches that have drawn focus to the long-term bonds that some banks bought in the pandemic-driven deposit surge. Those are proving problematic because a sharp rise in interest rates as part of the Fed’s effort to fight inflation means that longer-term bonds bearing lower interest rates can’t be sold without recognizing a loss that can hit capital.

“There is a lack of confidence in parts of the system right now,” said Jason Goldberg, an analyst at Barclays.

Bloomberg reported that Moody’s Investor Service was placing six regional banks on review for a possible downgrade in their creditworthiness.

Moody’s Investors Service placed First Republic Bank and five other US lenders on review for downgrade, the latest sign of concern over the health of regional financial firms following the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank.

Western Alliance Bancorp., Intrust Financial Corp., UMB Financial Corp., Zions Bancorp. and Comerica Inc. were the other lenders put on review by Moody’s. The credit rating company cited concerns over the lenders’ reliance on uninsured deposit funding and unrealized losses in their asset portfolios.

Yet even the usually iconoclastic ZeroHedge was reporting that many analysts saw these same banks as a good risk/reward prospect.

First Republic Bank jumped as much as 63% for its sharpest intraday gain ever, following a record Monday drop, while PacWest Bancorp surged 64% and Western Alliance Bancorp rose 53%. Meanwhile, bigger banks such as Bank of America and Citigroup also advanced. Meanwhile, Charles Schwab rallied as much as 18% after Ron Baron told CNBC earlier in the day that he had bought stock on Monday as it plunged.

Regional bank stocks “represent one of the best risk/reward in many years” in the wake of the rout, Baird analyst David George wrote in a Tuesday note, saying that "extreme fear and negative sentiment” have been driving the selloff, but “we believe the risk of contagion is generally low and believe investors should take advantage of weakness to add exposure to the group.” The view was echoed yesterday by Bill Ackman who tweeted that small banks are an "incredible bargain".

Investors are leery and uncertain about bank stocks, regulators believe several banks are not credit-worthy (i.e., solvent and/or liquid), yet bank stocks themselves are an “incredible bargain” investors should jump on post haste. That is the sum of what the media has divined from these shifts in the financial landscape.

What, therefore, should we make of these shifts? What are these signals telling us, if anything?

One message we can see persistently on display is that the Fed’s interest rate strategy for corralling inflation needs to be significantly adjusted, if not completely rethought. Even though the Federal Funds rate have not changed, yields are back where they were 6 months ago, which will further erode the increasingly problematic capacity of the Federal Funds rate to significantly impact market interest rates.

Nor should we pretend either that the decline in asset value triggered by the Fed’s rate hikes is anything other than the inevitable consequence of the strategy, with the rise in current yields destroying the value of legacy assets, as was noted at the end of February by FDIC Chair Martin Gruenberg, when he pointed out the $620 billion in unrealized losses sitting on the balance sheets of the nation’s banks.

Unrealized losses on available–for–sale and held–to–maturity securities totaled $620 billion in the fourth quarter, down $69.5 billion from the prior quarter, due in part to lower mortgage rates. The combination of a high level of longer–term asset maturities and a moderate decline in total deposits underscores the risk that these unrealized losses could become actual losses should banks need to sell securities to meet liquidity needs.

Regardless of how one feels about government intervention in putatively free markets, there is no avoiding the plain economic reality that those losses were to a degree created with every Federal Funds rate hike. By resetting the value of interest-bearing securities, the Federal Reserve effectively tanked the value of pre-existing assets.

Regardless of whether this was an intended consequence of the Fed’s hiking interest rates to rein in consumer price inflation, the unrealized losses are a direct result of that effort, and so would increase as the Fed raises rates. If and when the Federal Reserve raises rates again, so, too, will it increase those unrealized losses. For the Fed not to acknowledge this while making the issue even worse is simply reckless and irresponsible on their part.

Yet it must also be acknowledged that those losses did not arise overnight. The Federal Reserve has been raising interest rates for a year, and banks have had a year to assess the impact of raising rates on the various assets they hold. As even a quick scan of the Silicon Valley Bank balance sheet shows, the erosion of value in bank-owned interest-bearing securities is a problem that has developed over that year.

That SVB was faced with a liquidity crisis it could no longer conceal with ever-increasing FHLB “emergency” advances and loans is as much SVB’s doing as it is the Federal Reserve’s.

That banks overall are now faced with $620 Billion in unrealized losses on holdings of US Treasuries and other interest-bearing securities is as much a result of their inaction as it is the Federal Reserve’s actions. That banks refuse to acknowledge their role in creating that $620 Billion shortfall, as well as in any further deterioration in the fair market value of their interest-bearing securities is also undeniably reckless and irresponsible—and absolutely counterproductive.

The most disconcerting message we can take away from the surrealism of the past week’s series of banking events, however, is that the surrealism is not yet done.

Consumer price inflation may be cooling off and (slowly) coming down, but it is still at present far higher than the <2% inflation that has been the norm in this country literally for decades. The impetus for the Federal Reserve’s interest rate manipulation strategy has not gone away, nor is it likely to go away any time soon.

The $620 Billion in unrealized losses certainly is not going away any time soon. The value of the securities at the base of that pile of unrealized losses is permanently impaired as a direct result of the Federal Reserve’s rate hikes. Somehow, banks must deal with that shortfall and its impact on their both their balance sheet and their liquidity positions.

The mass panic that produced lethal bank runs may have subsided. The immediate viability of a number of smaller, regional banks might have been secured through the White House’ explicit guarantee of all bank deposits, Yet the root causes of both the mass panic and the disruption within the banking industry it catalyzed have not ended, and will likely only get worse.

We are by no means done with this story. There are many chapters yet to be told. Persistent consumer price inflation guarantees that those additional chapters will soon get told.

Welcome to interesting times.

I appreciate your efforts in rounding up all this data for us! My question is: what is your confidence level in the data itself, relative to your confidence in data given in past eras? Are the regulatory agencies ‘spinning’ the data more these days, just because it has become the government cultural norm? When the government says that inflation has lessened

Am I right in this rather simple line of thinking? If it weren’t for fractional lending, we wouldn’t have any of these problems?