Europe, led by Germany, could be facing an existential crisis catalyzed by the ongoing energy crisis.

Businesses, particularly heavy industry, need access to energy in order to operate. Because of the energy crisis, an increasing number of industrial firms are choosing to shut down rather than pay increasingly unaffordable energy costs.

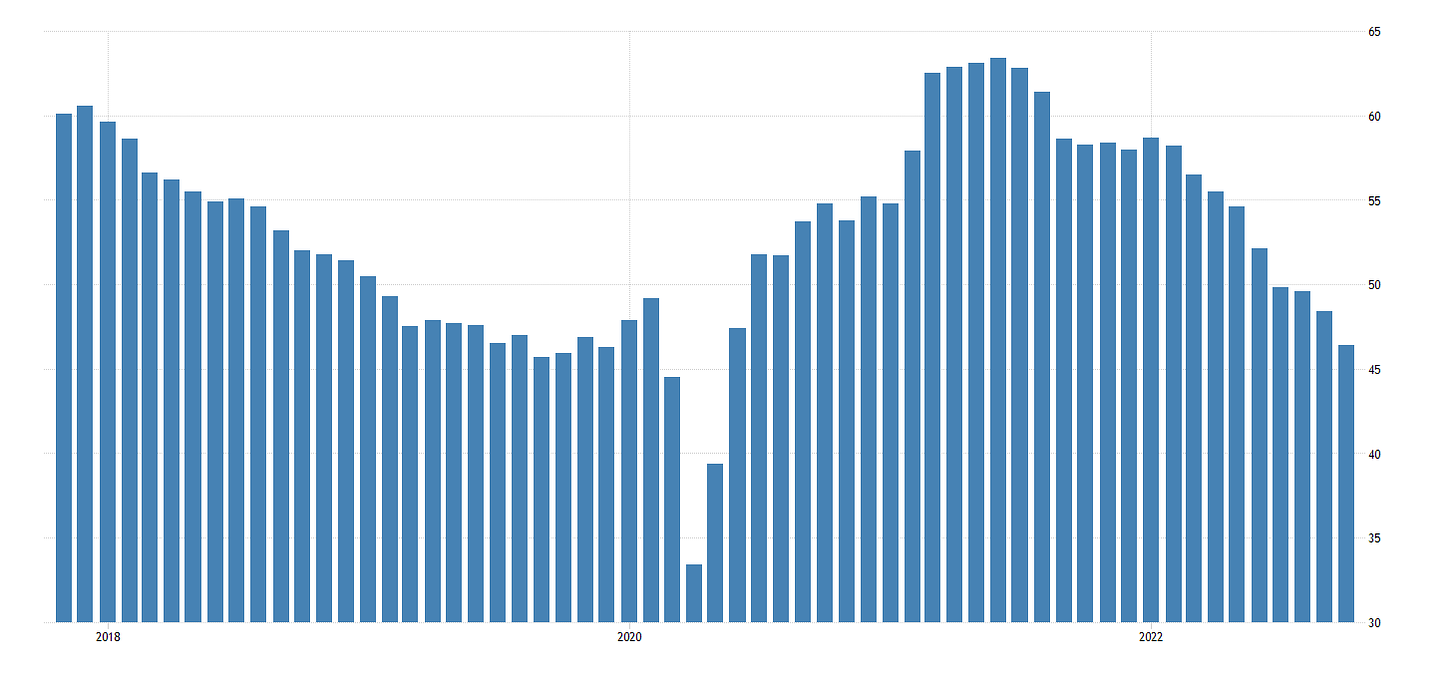

That the European Union is heading for a recession is now quite clear to anyone watching the indicators. The latest there—eurozone manufacturing activity—fell to the lowest since May 2020.

The October reading for S&P Global’s PMI also signaled a looming recession, falling on the month and being the fourth monthly reading below 50—an indication of an economic contraction.

Yet the challenge is not merely one of a downturn in the economic cycle. There are increasing signs that the damage to EU industry will be more or less permanent, with companies shuttering operations, never to restart them.

Germany Has No Ready Substitute For Russian Natural Gas

In what has to be the most extreme example of economic shortsightedness imaginable, Germany is leading the way in Europe’s burgeoning economic crisis due to the simple fact that they have never developed viable alternatives to cheap natural gas from Russia, natural gas that has been effectively shut off due to the Russo-Ukrainian War and the resultant economic sanctions laid up on Russia.

Almost 80 years later Vladimir Putin might achieve some of what Morgenthau, whose parents were both born in Germany, had in mind. By weaponising the natural gas on which Germany’s mighty industrial base relies, the Russian president is eating away at the world’s fourth-biggest economy and its third-biggest exporter of goods. It doesn’t help that at the same time, Germany’s largest trading partner, China, which bought €100bn ($101bn) of Germany goods last year, including cars, medical equipment and chemicals, is in the midst of a severe slowdown, too. A national business model built in part on cheap energy from one autocracy and abundant demand from another faces a severe test.

Exactly how German did not foresee the inevitable consequences of suddenly ostracizing their primary energy supplier is a question that will have to wait for a different article. What is crucial at the moment is that Germany has been attempting to substitute low-cost Russian natural gas with high-cost US liquified natural gas (LNG).

Germany is signing long-term contracts for U.S. LNG to save itself, though it will have to find a place to put it all. For this reason, they will have to build new terminals to handle those shipments quickly.

Without sufficient LNG terminals, there is an upper bound to how much LNG Germany can effectively buy, regardless of what the demand for LNG is.

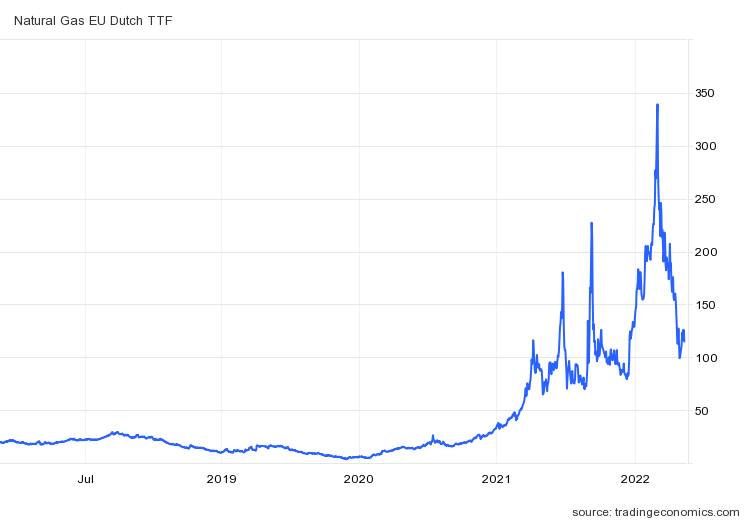

Yet it is important to realize also that the Russo-Ukrainian War is only the latest supply shock to hit European natural gas supplies, and while natural gas prices today are roughly double what they were in November of 2021, in November of 2021 natural gas prices were four times what they were in November of 2020. Natural gas prices in Europe, as measured by the TTF Gas prices (listed in euros per Megawatt hour of electricity generated) have increased 800% at least in the past two years.

The sharp rise in natural gas prices in 2021 makes the EUs unpreparedness for the consequences of isolating their primary natural gas supplier in 2022 particularly mystifying, given that they had already seen major price spikes in the previous year.

Energy Costs Are The Most Noticeable Problem, But Not The Only Problem

Germany’s economic woes are compounded by more than just energy costs. Labor costs are already high and likely to rise even higher.

Big multinational companies often have factories in other countries where energy is cheaper. But many, including basf, with its vast city-sized complex in Ludwigshafen, nevertheless continue to produce a lot at home. Even if costs of raw materials moderate, as some have begun to, and the government comes to the rescue with energy-related support, as it has vowed, cost pressures will not disappear. In particular, companies are bracing for a brutal round of annual wage negotiations with Germany’s powerful unions. Those between ig Metall, Germany’s biggest union, and employers in the mighty car industry, are about to kick off. “The ig Metall will not accept anything below an 8% increase,” predicts Ferdinand Dudenhöffer of the Centre Automotive Research, a think-tank.

In addition, the EU regulatory environment has grown increasingly tight and unfriendly to business, making the relocation of major industrial facilities outside of Europe increasingly attractive.

Yet it is worth noting that the energy crisis was not the only reason for BASF’s plans to shrink its presence at home and grow abroad. Increasingly tighter EU regulation was also a factor behind this decision, Brudermueller said.

Other industries also seem to have problems with new EU regulations. The trade body for the steel and aluminum industries, which have also suffered significantly from the energy cost inflation, recently proposed that the EU takes a gradual approach with its new Cross-Border Adjustment Mechanism, also known as the import carbon tax.

In Germany especially, EU regulations purporting to combat “climate change” are working principally by driving out business. In addition to BASF decamping to China, Arcelor Mittal is closing two steel mills in Germany.

The regulatory burden is having impacts across the economic spectrum, not only exacerbating the energy crisis but making its economic fallout more permanent damage.

A tenth of Europe’s crude steel production capacity has already been idled, according to estimates from Jefferies. All zinc smelters have curbed production, and some have shut down. Half of the primary aluminum production has shut down as well. And in fertilizers, 70 percent of factories have been idled because of the energy shortage.

Chemical plants are also curbing their activities, ferroalloy furnaces are going cold, and plastics and ceramics manufacturing is shrinking as well.

Some of these businesses might choose to eventually relocate to a place with cheaper and more widely available sources of energy, contributing to the deindustrialization process in Europe. As for the best candidate for this relocation, according to some observers, it is the United States, with its abundant gas reserves, rising production, and friendly investment climate.

Europe’s economic crises are in no small measure the result of self-inflicted injuries, courtesy of the EU regulatory superstate.

Europe Is Reducing Its Energy Consumption By Being Closed For Business

While the EU has succeeded in reducing its energy consumption in recent months, the reality is that it has done so at the expense of both current and future industrial operations.

EU Manufacturing PMI has been in contraction territory for four months as of this writing, with the contraction getting steadily worse each month.

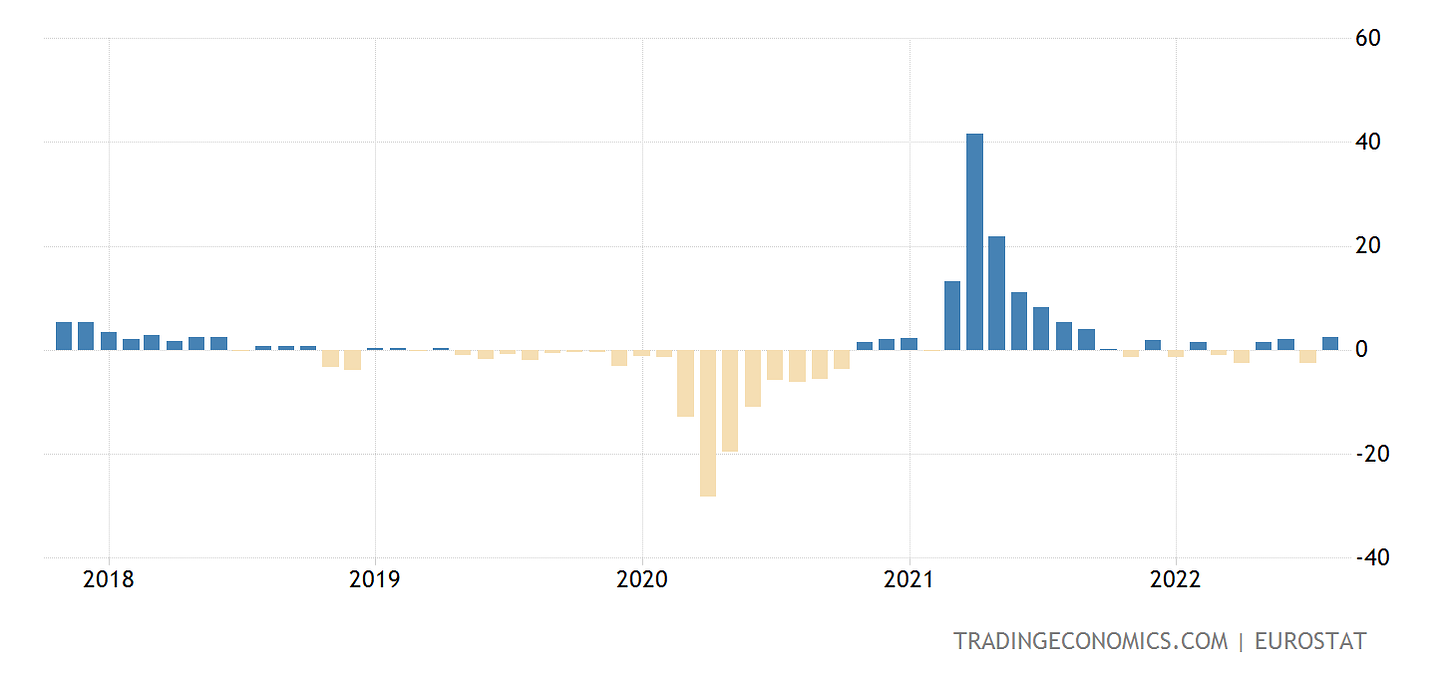

While EU industrial production has had some months of positive output, 2022 has so far been an on-again/off-again cycle where one month of positive output is followed by one or two months decreasing output.

Having suffered a year of decline before the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns in 2020, the last thing European industry needs is yet another year of declining and contracting industrial output, and yet it is about to endure exactly that.

Previously, I have observed how the energy crisis for Europe is a crisis of change, that it is being challenged to find new sources of energy and new ways to fuel its industries.

However, if current trends continue, there is a grave risk for European industry that, far from adapting to the energy shortage, European industry will be ended because of it.

Seems to be fulfilling a globalist (no smoke) pipe dream?

"Germany is leading the way in Europe’s burgeoning economic crisis due to the simple fact that they have never developed viable alternatives to cheap natural gas from Russia"

Gosh, who could possibly have foreseen this?

Oh wait, someone did. But the Germans laughed at him.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FfJv9QYrlwg