You Can't Push A String

The Federal Funds Rate Is A Weak Means For Pushing Up Interest Rates

Over the past year, Wall Street analysts and economists have become something akin to latter-day Kreminologists, only instead of reading the tea leaves and parsing every little comment to divine the inner machinations of Soviet Russia, they spend their days parsing every comment by a Federal Reserve President or the Fed Chairman himself Jerome Powell to divine the future interest rate machinations of the Federal Reserve.

Just last week former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers, in an interview on Bloomberg’s “Wall Street Week”, suggested that the Federal Reserve would have to push interest rates even higher than the currently forecast “terminal rate” of 4.6% to corral inflation.

“I’m moving upwards my view on the possibilities for the terminal rate,” Summers told Bloomberg Television’s “Wall Street Week” with David Westin, referring to the end-point for the Fed’s rate-hiking campaign. “It’s not what I would expect but it would not surprise me if the terminal rate reached 6 or more,” he said.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell and his colleagues on Wednesday boosted their target for the federal funds rate to a 3.75% to 4% range. Powell said in his press conference that policymakers may need to lift the rate past the 4.6% level that was referenced in the Fed’s September projections for next year -- though he stopped short of specifying any new peak.

There are two problems with Summers theory, however: 1) Interest rates are not moving at all in connection with inflation at the moment; and 2) can the Federal Reserve even get the “terminal rate” to 6%?

Consumer Price Inflation Is Marching To Its Own Drum

What neither Wall Street nor the Federal Reserve wishes to acknowledge, consumer price inflation, as measured by the Consumer Price Index, has been very much marching to its own drum, without regard to changes in interest rates.

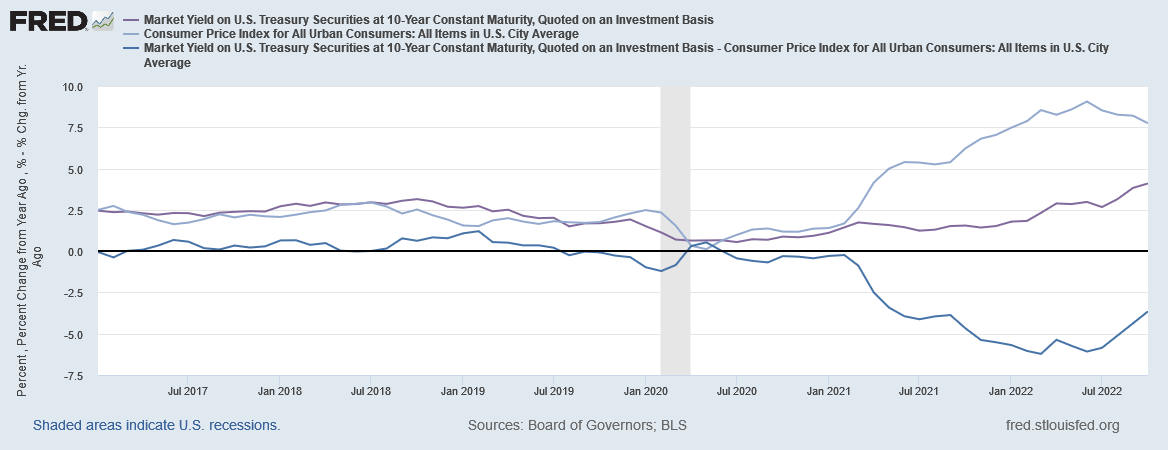

Even as inflation began heating up starting in January of 2021, the yield on 10 Year Treasuries did not change much, with the result that real yields1 on the 10 Year Treasury went from slightly negative to extremely negative.

Most notably, the real yield on the 10 Year Treasury did not begin rising back towards zero until July, well after the first rate hikes had been announced by the Federal Reserve.

The reason for this plunge in real yields during 2021 is not hard to fathom. As inflation rose, nominal yields did not—certainly they did not rise in proportion to the rise in inflation.

In January 2021, the nominal yield on the 10 Year Treasury was 1.11%, and inflation stood at 1.40%. By February of this year, one month before the first Fed rate hike, the nominal yield had risen to 1.83%, while inflation had risen to 7.87%. In other words, interest rates had risen by 64.9%, while inflation had risen by 462.1%.

When inflation peaked in June at 9.05%, the nominal yield on the 10 Year Treasury had risen to 2.83%. Starting from January 2021, that works out to a 150% rise in interest rates and a 546.4% rise in inflation.

This was after the Fed raised the Federal Funds Rate twice.

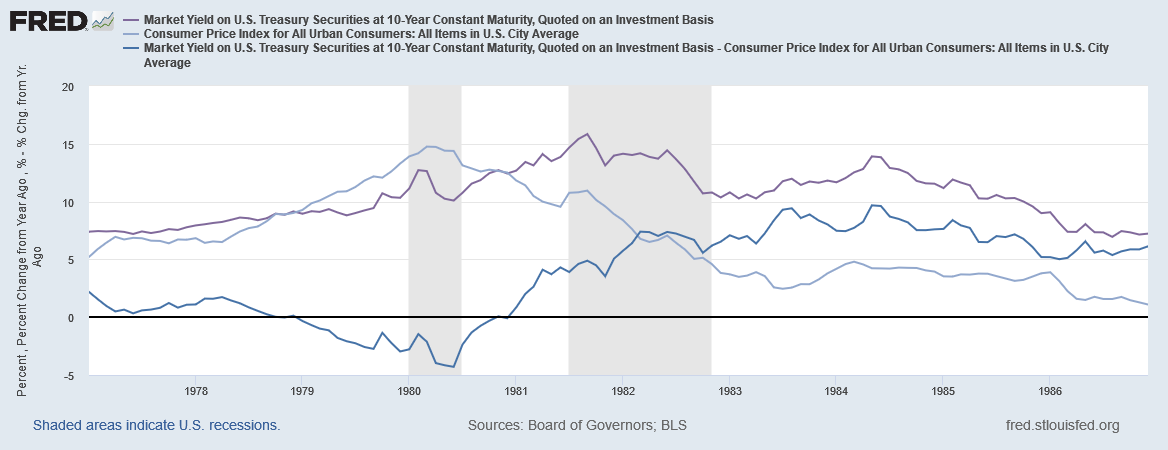

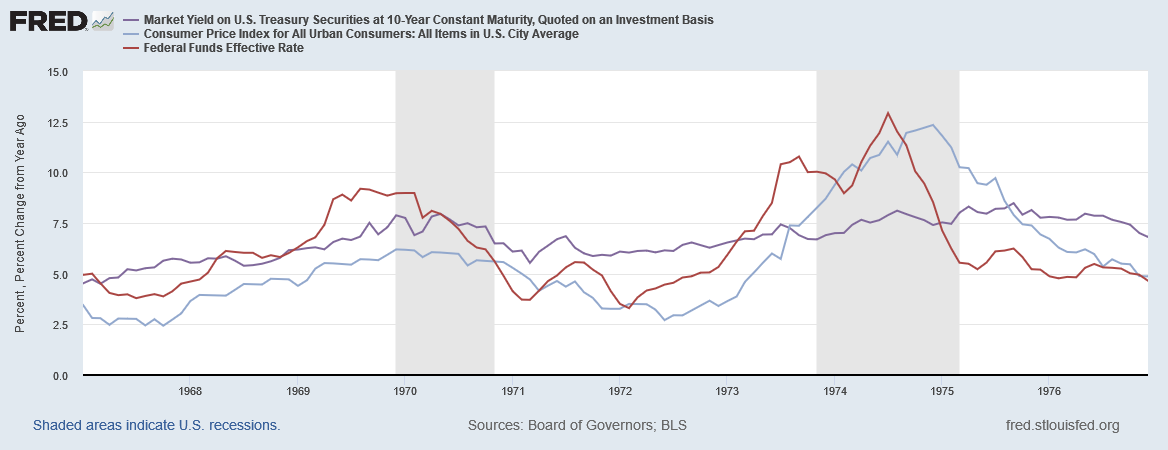

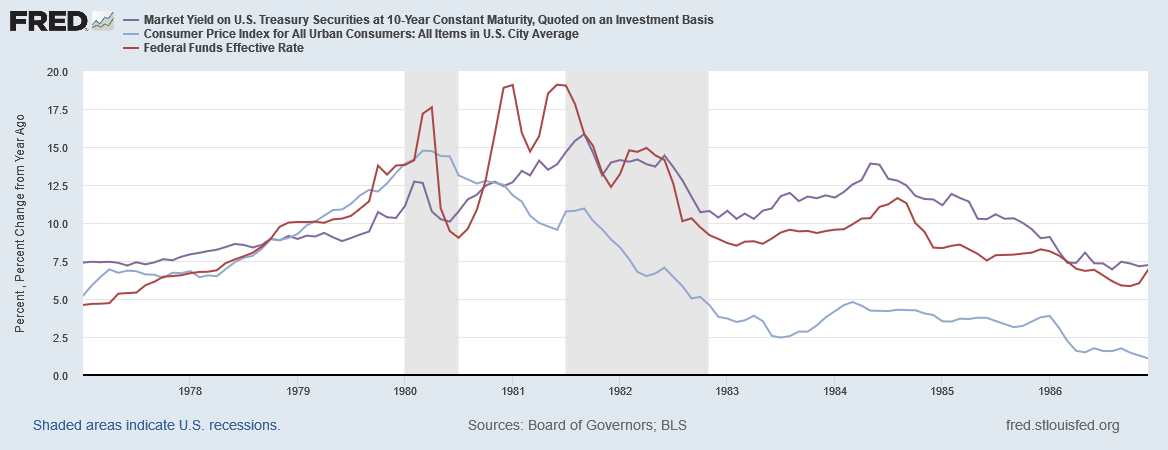

Nor is this an isolated case. Just prior to the Volcker rate hikes starting in 1979, inflation also moved without much regard for interest rates. In April of 1978, consumer price inflation printed at 6.5%, and the nominal yield on the 10 Year Treasury printed at 8.24%. During the first phase of the Volcker Recession, inflation would peak in March of 1980 at 14.77%, while nominal yields on the 10 Year Treasury would peak a month earlier at 12.64%. That is a 53.4% rise in interest rates, but a 127.2% rise in inflation over the same period.

Note again that the peak came after former Fed Chair Paul Volcker began hiking the Federal Funds Rate hoping to choke off inflation with high interest rates.

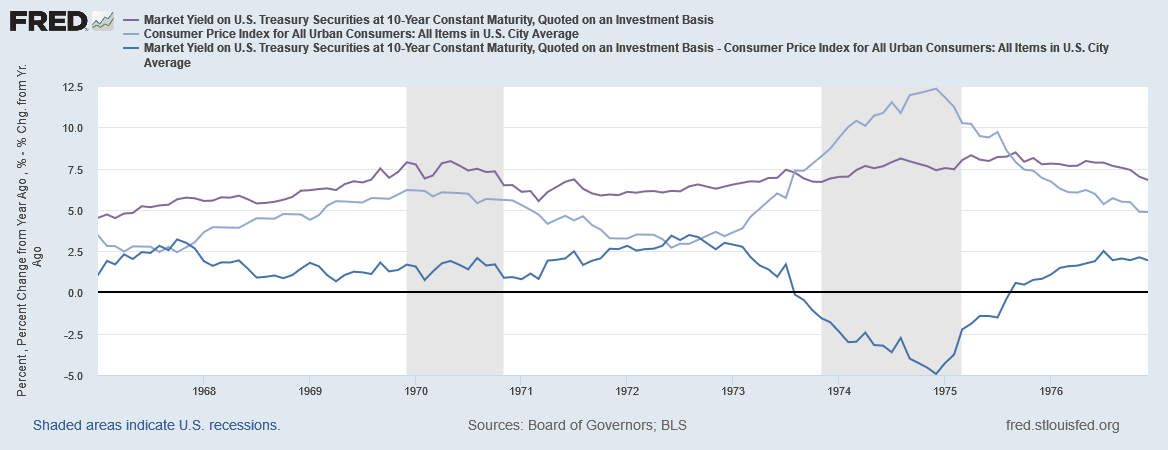

Going back to the 1974 recession, when inflation surged above the nominal yield for the 10 Year Treasury, the same pattern plays out. Starting with inflation’s low point in June of 1972, when inflation stood at 2.7%, the nominal yield on the 10 Year Treasury was 6.15%. Inflation would peak in December of 1974 at 12.34%, but the nominal yield actually peaked 4 months earlier at 8.11%.

That’s a 31.9% increase in interest rates against a 357% increase in inflation.

While “this time” is different in many ways, one way in which “this time” is the same as prior periods of inflation is that inflation does not pay much attention to interest rates, nor vice versa.

How, then, does Larry Summers conclude at pushing interest rates to 6% will have the desired impact on inflation? Inflation has disregarded a 6% interest rate level before. There is every reason to believe it could do so again. There is no reason to assume a 6% interest rate will corral inflation.

Treasury Yields Don’t Always Mind The Federal Funds Rate

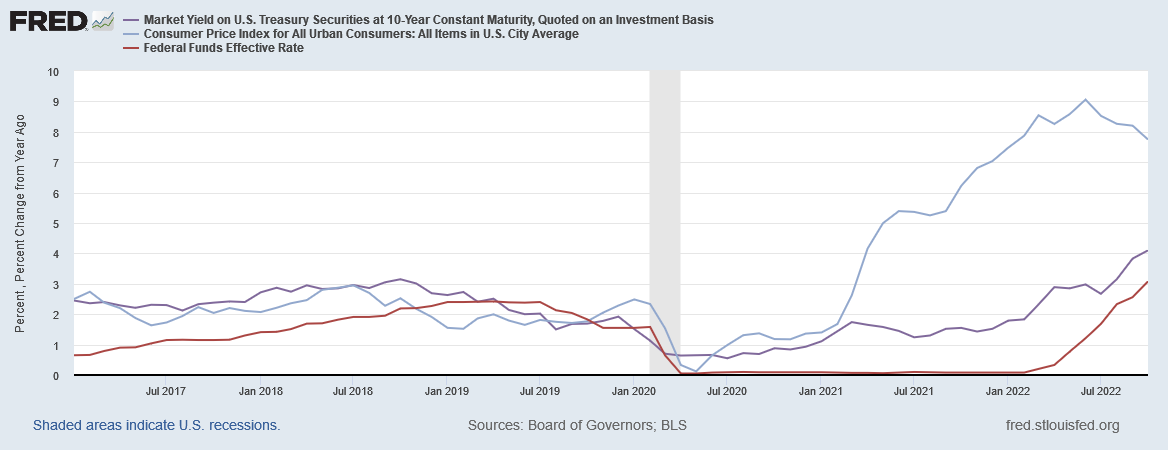

Not only do inflation rates do as they please no matter what the interest rate is, interest rates in the form of Treasury Yields tend to follow the Federal Funds Rate only slightly.

We should be mindful that Treasury Yields do react to Federal Funds rate hike announcements. We see that demonstrated every time the Fed hikes rates—immediately thereafter Treasury Yields move up.

But we should also remember that, as shown above, the 10 Year Treasury yield rose 64.9% between January 2021 and February 2022 without any boost from the Federal Funds rate.

As of October, before the last Federal Funds rate hike, the Federal Funds rate was 3.08%, whereas in February, it was at 0.08%. That is a three thousand seven hundred fifty percent rise in the Federal Funds rate.

Yields on 10 Year Treasuries in October printed at 4.1%. Rising up from February’s 1.11% yield is an increase of only 269.4%.

That is not exactly the kind of impact on interest rates one expects the Federal Funds rate to have—i.e., minimal at best.

Even though the absolute increase in the Federal Funds rate of ~3% is more or less matched by the absolute increase in the 10 Year Treasury yield, it is quite possible that is merely coincidental. Certainly we do not see a similar tracking of absolute interest rate hikes betweeen the Federal Funds rate and the 10 Year Treasury yield during the 1974 recession example.

In June of 1972, the Federal Funds rate stood at 4.46%, and would peak just before treasury yields in July of 1974, printing at 12.92%. That is a relative increase of 189.7% and an absolute increase of 8.46% in the Federal Funds rate. Remember, during that episode yields rose 31.9% in relative terms, which was 1.96% in absolute terms.

Even the Volcker rate hikes do not show substantial strength in influencing interest rates. In September 1979, the Federal Funds rate was 11.43% and the nominal yield on 10 Year Treasuries was 9.44%. The Federal Funds rate would ultimately peak in June 1981 at 19.1%, with nominal yields peaking shortly after 15.84% in September 1981.

That is a relative increase in the Federal Funds rate of 67.1%, and an absolute increase of 7.67%. During that period, nominal yields actually came close to matching the Federal Funds rate in terms of a relative increase, at 67.8%, but with an absolute increase of 6.4%.

Looking at the current interest rate situation, from February to June, the Federal Funds rate rose from 0.08% to 1.21%, while the 10 Year Treasury yield rose from 1.11% to 2.98%. That’s a rise of 1.13% in the Federal Funds rate (113bps) to achieve a 1.87% (187bps) rise in Treasury yields.

From June to October, the Federal Funds rate rose to 3.08% while 10 Year Treasuries rose to 4.1%. That’s a 1.87% (187bps) rise in the Federal Funds rate to achieve a 1.12% (112bps) rise in Treasury yields. A larger rise in the Federal Funds rate is accompanying a smaller rise in interest rates.

The Federal Funds rate is at best an extraordinarily “hit or miss” proposition for regulating interest rates. An announced change in the Federal Funds rate does produce a transitory shift in yields, but in between announcements yields can move up and down in response to a variety of other forces.

You Can’t Push A String

Relying on the Federal Funds rate to regulate treasury yields and, by extension, market interest rates broadly, has all the efficacy and smoothness of trying to push a string from one end and expecting it to stay straight. Eventually, enough string bunches up to where you can move it, but relative to the energy needed to move the string pushing it is extremely wasteful.

Taking this year’s rises in both the Federal Funds Rate and 10 Year Treasury Yields, if the absolute rises in the Federal Funds rate continues to result in a similar absolute rise in the 10 Year Treasury yield, the Federal Funds rate has to rise another 2%, or 200bps. That would put the Federal Funds rate at about 5%-5.1%, a total relative rise to where rates started off this year of 6,250%, to achieve a relative rise in yields of ~450%.

However, if the Fed continues to see diminishing returns to rate hikes, to get 10 Year Treasuries up to 6%, the Federal Funds rate will have to rise by quite a bit more—in essence, a replay of the Volcker rate hikes where the Federal Funds rate exceeded Treasury yields for an extended time. While there is insufficient data to establish a precise rate of decay for the Federal Funds rate stimulating Treasury yields, the Fed may very well need to double the Federal funds rate from where it is today, just to push (and then pull) the 10 Year Treasury yield up to 6%. That means a Federal Funds rate of of 7% or even 8% is not at all out of the question.

All that to achieve an impact on interest rates that is problematic at best.

While few will argue that reining in inflation is good monetary policy, that does not make every plan instituted in furtherance of reining in inflation a good plan. At the present time, constantly raising the Federal Funds rate shows no indication of being a productive plan, in that it is having only minimal impact on inflation if even that.

The numbers simply do not support continued rate hikes as a viable inflation-fighting strategy. It is debatable whether continued rate hikes were ever the inflation-fighting strategy the Volcker myth claims that they are.

What is not debatable is that the current Fed strategy on inflation is not working.

“Real Yields” are the nominal yield (stated as an annual percentage rate) less the year on year percent change in the CPI.

I'm not sure pushing on a string is the right analogy. It's like being at the helm of a good-size boat. They don't respond to control inputs instantly, so inexperienced people will almost inevitably over-control them.

Mortgage rates have more than doubled from ~3% to ~7%. This will inevitably cause a decline in housing prices, which has already started, but sellers are stubborn and it will take time before the full effect is apparent. When you have a substantial decline in real estate prices, people who feel well-off now due to all the paper gains/equity they have in their homes will be less inclined to spend money. The same is true the people's 401ks take a hit via a decline in the stock markets. None of this happens instantly, but it will happen, and then the demand side of things will shrink, which will reduce pressure at least some prices.