One of the greatest rewards writing this Substack brings me are the stimulating comments and observations made by readers, both here and on various social media.

I received one such comment the other day in an X/Twitter chat room in response to my article on the Russian Central Bank’s recent interest rate hikes, and the question I posed at the end.

The return of inflation is a stark reminder of an essential question about war that Putin must daily confront regarding Ukraine: how much Russian treasure is he prepared to expend to achieve the war’s objectives?

To this a Twitter user (who shall remain anonymous, as this was not in a public forum) replied:

If not ALL but most of it!!! Putin will not let NATO and US coalition invade his Country!!! Which might be the next case scenario likely to happen if Biden sends Troops over there, as alleged!!

This begs the question: could NATO invade Russia? More precisely, was or is NATO planning or preparing an imminent invasion of Russia?

While there will (and should be) ongoing debate over NATO policy towards Russia, actual military invasion itself becomes largely a question of numbers and logistics: are there troops in position to launch an attack? Are there sufficient supplies and material stockpiled to sustain the attack?

Without delving into the policy questions, it is still instructive to examine those questions of numbers and logistics, for they can tell us how imminent any threat perceived by Vladimir Putin from NATO was and is.

I will begin this analysis with an important disclaimer: This is not an exploration of whether or not either the US or NATO should support Ukraine in this conflict, nor is it addressing either real or imagined political flaws within Ukraine itself nor even of Russia. Regardless of the accuracy of Putin’s perceptions of an imminent NATO threat of invasion, arguments for or against supporting Ukraine encompass far more than mere troop numbers and deployments. I am not addressing such questions here, and I am far from certain there is a suitable framework for me to address such questions here.

As I have said in multiple comments and on Substack Notes, what I want to see in Ukraine is peace. I want to see Russian and Ukrainian soldiers both not fighting and not dying. I want to see an end to attacks both on Ukrainian cities and on Russian cities. Regardless of the politics, the reality of any war is that blood is being shed. My desire is that no more blood be shed.

With my stance on Ukraine hopefully made clear, let us begin by examining the troop numbers that have been reported as the size of Russia’s invasion force in February, 2022. The level of success Russia has enjoyed in capturing Ukrainian territory arguably gives us a framework for gauging how many troops would be needed to invade going the other way, into Russia.

Estimates vary, but the number of Russian troops which crossed Ukraine’s border on February 24 appears to have been between 150,000 and 200,000 troops altogether.

Estimates of Russian troop numbers in Ukraine have ranged from anywhere between 100,000 and 200,000 in recent weeks.

Ukraine's defence minister, Oleksiy Reznikov has put Russian forces surrounding the country at 149,000, while President Volodymyr Zelenskiy estimated the figure at around 200,000, in addition to thousands of combat vehicles, which include an estimated 2,840 battle tanks, outnumbering Ukraine’s armoured capability by three to one.

Reznikov’s estimate is in line with US calculations of around 150,000 Russian troops massed on Ukraine’s borders before the invasion began on Thursday. Russia keeps a static border presence of around 35,000 military personnel on the Ukraine frontier, from a total standing army – the Russian Ground Forces - of 280,000 active duty personnel. Overall, Russia maintains the fifth-largest armed forces in the world, with over one million active personnel and two million reservists split between the various branches, which includes air force, navy, space forces, strategic missile forces, airborne and special operations forces.

This range is consistent with prior reporting in 2021 regarding the buildup of Russian forces near the border with Ukraine, which in November some assessments indicated there were some 115,000 troops poised for attack.

“Renewed conflict in Ukraine would pose an immediate challenge to NATO, and Putin is likely betting on a disorganized and patchwork response,” private intelligence firm The Soufan Center wrote in an analysis note late Monday.

It assesses Moscow has mobilized as many as 115,000 Russian forces as a part of the campaign to intimidate Ukraine. Russia has also employed other forms of pressure on Kyiv and its allies, including weaponizing its energy reserves, which, according to Soufan, foreshadows “a difficult several months in Western Europe as winter approaches.”

Thus, on the high side Russia invaded Ukraine with approximately 200,000 troops. Those 200,000 troops succeeded in seizing by April a large swath of eastern Ukraine, after which their efforts began to stall.

Without taking into account disparities in the combat capabilities of Russian vs NATO military formations, as well as the disparities that have almost certainly existed between Russian and Ukrainian forces, one can argue with substance that Russia attacked with too few men. One can plausibly assess that Russia should have attacked with many times that 200,000 initial troop strength in order for Russia to conquer and hold most or all of Ukraine. If 200,000 Russian troops was only sufficient to occupy and hold the eastern part of Ukraine, with more Russian forces deployed to the invasion force Russia arguably could have at the very least occupied more of Ukraine.

Given that Russia is many times larger than Ukraine, it is almost certain, therefore, that NATO would need many times more than 200,000 troops if it wished to prosecute an invasion of Russia from Ukraine.

We also have some historical confirmation of this, for when Nazi Germany launched Operation Barbarossa and invaded Russia, some 3 million German Soldiers were involved1.

On June 22, 1941, over 3 million German troops invade Russia in three parallel offensives, in what is the most powerful invasion force in history. Nineteen panzer divisions, 3,000 tanks, 2,500 aircraft, and 7,000 artillery pieces pour across a thousand-mile front as Hitler goes to war on a second front.

We can therefore safely assume that a NATO invasion of Russia would require a similar number of troops—3 million.

Immediately this begins to present a numbers problem for the premise of an imminent NATO invasion of Russia. NATO’s member countries all told can field a total fighting force of approximately 3.5 million men, according to NATO’s Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe2.

If NATO were to invade Russia, it would most likely require the entire troop strength of every member nation combined. That’s a fairly drastic level of military commitment, particularly as it would then strain the defense postures of those nations against threats from other sources besides Russia.

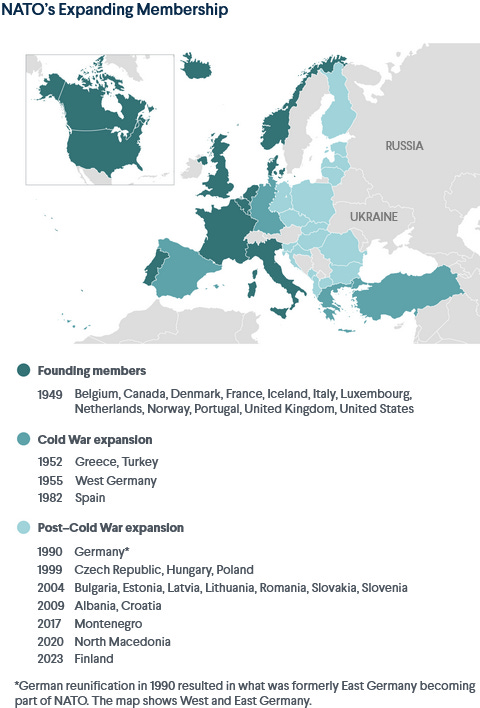

We should pause here to note that such a commitment is by no means impossible, nor is it necessarily implausible as an hypothetical. NATO exists, first and foremost, as an alliance to deter potential Russian aggression in Europe. That was the animating idea behind the alliance when it was crafted in 19493.

In this regard, one could plausibly argue the NATO alliance was, at least during the Cold War, a strategic success4.

For over seven decades, NATO has endured, even as the common foe that it was organized against—the Soviet Union—disappeared. It successfully protected its members against Soviet aggression; no NATO member was ever attacked by the Soviet Union.

The extent to which such a threat was realistic will forever be a matter of historical conjecture. If one presumes Russian invasion of Europe was inevitable, then the NATO alliance arguably becomes a deterrent force that has forestalled such invasion. However, as such an invasion has never actually occurred, the actual deterrent effect of NATO is inherently problematic. Earth has never been invaded by space aliens, yet one would hardly claim that the US Space Force is one of the reasons why!

Yet this perceived threat of Russian aggression in Europe must be acknowledged, because that perceived threat is what has informed NATO policy and posture since its inception, and, as a consequence, has gone on to inform Russia’s perceptions of NATO as an anti-Russian alliance (which, to be fair, it is). More on this point later.

While an all-out invasion of Russia by NATO is never outside the realm of strategic possibility, however, the strategic reality is that the bulk of NATO’s 3.5 million potential troops are not deployed anywhere where an invasion of Russia can be started.

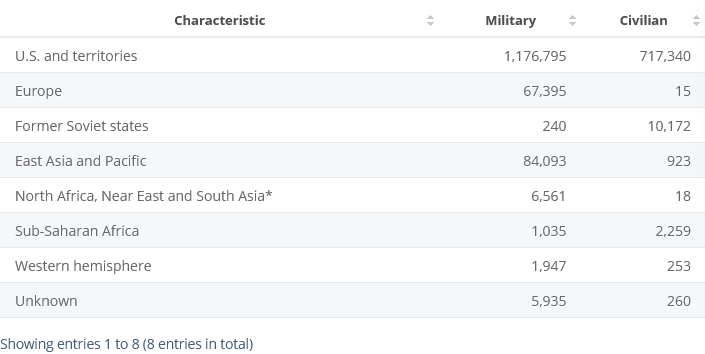

By far the largest military component of NATO forces is the United States military, with some 1.3 million personnel available.

However, prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine the number of US troops in Europe was reported as being approximately 74,000.

Around 74,000 U.S. military personnel are stationed in Europe today, according to the U.S. Congressional Research Service, but not all are active-duty troops.

Germany hosts some 36,000 U.S. troops, Italy around 12,000, Britain some 9,000, Spain some 3,000 and Turkey 1,600. The United States also rotates about 4,500 troops through Poland but they are not stationed permanently. Many of these forces can be deployed on behalf of NATO.

Even if one added all troops from all other NATO members, the presence of just 74,000 US troops leaves NATO troop strength well short of 3 million.

Moreover, most European military forces are not currently deployed in any coordinate posture either to invade Russia or to repel an invasion of NATO territory by Russia.

According to Reuters, in January 2022, there were a total of about 4,000 troops deployed in Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia, and Poland, to act as a sort of “tripwire” against a Russian invasion.

In Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia and Poland, NATO has about 4,000 troops in multinational battalions, backed by tanks, air defences and intelligence and surveillance units.

Described by NATO as combat-ready, the light force presence is designed as a trip wire that would trigger reinforcements in the event a Russian incursion.

In the event of a Russian invasion of the Baltic states, these battalion sized forces presumably would be immediately reinforced or told to retreat, depending on the situation on the ground.

A further force of 4,000 multinational troops is stationed in Romania, in addition to an unspecified number of US troops deployed there. This likely would be another tripwire configuration.

NATO also maintains a 40,000-strong rapid response force. This force ostensibly is to give NATO immediate-response capability to emergent crises anywhere in the world5.

The NRF has the overarching purpose of being able to provide a rapid military response to an emerging crisis, whether for collective defence purposes or for other crisis-response operations.

The NRF gives the Alliance the means to respond swiftly to various types of crises anywhere in the world. It is also a driving engine for NATO’s military transformation.

The NRF provides a tangible demonstration of NATO’s cohesion and commitment to deterrence and collective defence. Each NRF rotation has to prepare itself for a wide range of tasks. These include contributing to the preservation of territorial integrity, making a demonstration of force, peace-support operations, disaster relief, protecting critical infrastructure, and security operations. Initial-entry operations are conducted jointly as part of a larger force to facilitate the arrival of follow-on troops.

On top of the tripwire deployments and the NRF, NATO also has some 3,500 troops on peacekeeping missions in Kosovo. In the event of a military crisis affecting Europe, these troops could likely also be utilized.

Based on these numbers, just prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, NATO could immediately field roughly 125,000 troops to counter a Russian invasion or to launch an invasion of Russia.

In the immediate aftermath of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, US troop strength was increased, and by the beginning of March was over 100,000.

The additional US troops increases the immediately deployable troops within NATO to 151,500.

By March of 2022, then, NATO had prepared formations of roughly the same total size as the formations Russia used to invade and occupy only a portion of Ukraine.

Both before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and after, there has been no reporting to suggest that NATO had assembled or is assembling an invasion force with which to attack Russia.

This last point is important, because it provides valuable context for assessing Putin’s prepared statement both announcing and justifying the invasion of Ukraine as a “special military operation.”

In the opening paragraphs of his February 24, 2022 address, Putin spoke of NATO’s eastward expansion as a security threat to Russia.

I will begin with what I said in my address on February 21, 2022. I spoke about our biggest concerns and worries, and about the fundamental threats which irresponsible Western politicians created for Russia consistently, rudely and unceremoniously from year to year. I am referring to the eastward expansion of NATO, which is moving its military infrastructure ever closer to the Russian border.

It is a fact that over the past 30 years we have been patiently trying to come to an agreement with the leading NATO countries regarding the principles of equal and indivisible security in Europe. In response to our proposals, we invariably faced either cynical deception and lies or attempts at pressure and blackmail, while the North Atlantic alliance continued to expand despite our protests and concerns. Its military machine is moving and, as I said, is approaching our very border.

There is some truth in this. Russia has consistently opposed the addition of former Warsaw Pact countries in the NATO alliance. One does not need to be a military strategist to understand why: adding Warsaw Pact countries to NATO moves the frontier between an avowedly anti-Russian alliance and Russia ever closer to Moscow6.

Russia has insisted many times that, during the denouement of the Soviet Union, NATO and US leaders had pledged not to expand NATO eastward.

Russian officials say that the U.S. government made a pledge to Soviet leaders not to expand the alliance’s eastern borders, a commitment they say came during the flurry of diplomacy following the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and surrounding the reunification of Germany in 1990. Proponents of this narrative often cite the words that U.S. Secretary of State James A. Baker said to Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev in February 1990, that “there would be no extension of NATO’s jurisdiction for forces of NATO one inch to the east.” They say the United States and NATO have repeatedly betrayed this verbal commitment in the decades since, taking advantage of Russia’s tumultuous post-Soviet period and expanding the Western alliance several times, all the way to Russia’s doorstep in the case of the Baltic states.

Unsurprisingly, US and NATO leaders remember these discussions differently, and interpret Baker’s words far more narrowly.

However, no matter what the intent behind those words then, there is no denying that Russia since has viewed NATO expansion as an ongoing threat against Russian integrity and Russian sovereignty. When Clinton spoke openly of NATO expansion in 1993, Russia’s then-President Boris Yeltsin was quite displeased, and warned NATO of the inevitable geopolitical consequences of such an expansion.

Yeltsin warned Western leaders at a conference in December of that year that “Europe, even before it has managed to shrug off the legacy of the Cold War, is risking encumbering itself with a cold peace.”

Yet while Russia even before Putin viewed NATO expansion as a threat, and even as an existential threat, it has never been characterized even by Putin in his February 24, 2022 speech as an imminent threat. In that speech, Putin spoke of NATO and US military actions against Serbia and in the Middle East. However, Putin also characterized the diplomatic exchanges between Russia and the US/NATO in December 2021 as focused on “European security and NATO non-expansion.”

Despite all that, in December 2021, we made yet another attempt to reach agreement with the United States and its allies on the principles of European security and NATO’s non-expansion. Our efforts were in vain. The United States has not changed its position. It does not believe it necessary to agree with Russia on a matter that is critical for us. The United States is pursuing its own objectives, while neglecting our interests.

This assessment is broadly consistent with Russian statements made in the fall of 2021 when there was growing concern within Europe about Russia’s military buildup along the Ukrainian border.

“Russia is not going to attack anyone,” Dmitry Peskov, a spokesman for Russian President Vladimir Putin, told reporters Tuesday morning, according to a translation of his remarks. “It’s not like that.”

He added, however, that Russia remains “deeply concerned about provocative actions of the Ukrainian Armed Forces on the line of contact” as well as “preparations for a possible military solution to the Donbas problem.”

Peskov’s comments come amid widespread concern in Western capitals that Russia is mobilizing for an invasion of its former Soviet-era satellite state. American intelligence officials have reportedly briefed their European counterparts about the potential for military action against Ukraine. And the top military intelligence official in Kyiv said earlier this week he believes Russia is positioned to invade at some point before the end of January.

These statements would be reiterated at high-level talks between the US and Russia in January, 2022.

Top U.S. and Russian diplomats said they had constructive talks Monday in Geneva, but they did not achieve a breakthrough in their attempt to defuse tensions regarding the Russian troop buildup on the Ukraine-Russia border.

Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov emerged from the nearly eight hours of talks and declared, "There are no plans or intentions to attack Ukraine." He went on to say, "There is no reason to fear some kind of escalatory scenario."

What we are to make of these statements—and, indeed, of the entirety of the eleventh-hour diplomatic efforts prior to the invasion of Ukraine—is itself a topic for discussion. The significance of them here is that they support a context for Putin’s speech announcing the “special military operation” as addressing largely a long-term strategic threat perceived by Russia from NATO, centered largely on potential further expansion of NATO by adding Ukraine. What they do not provide is a context for Putin’s speech that suggests a NATO or Ukrainian force was mobilizing to invade Russia proper in the fashion that Russia was mobilizing the troops that would cross the border into Ukraine on February 24, 2022.

The available contexts of Putin’s speech leave us without any substantive basis to presume that NATO was planning an imminent invasion of Russia proper in early 2022. Based on Putin’s own words, the nature of the threat perceived by Russia was the constant ongoing threat of having an avowedly anti-Russian alliance moving ever closer to the Russian heartlands. As Putin himself stated in his speech, “the situation for Russia has been becoming worse and more dangerous by the year.”

Could NATO invade Russia? Of course it could. It has the military manpower and arguably the logistics infrastructure for an undertaking that massive.

Would NATO have invaded Russia at some point, but for the war in Ukraine? While in the immediate term the answer is almost certainly “no”, would that answer hold true looking forward into the next decade? That we cannot say—again, NATO has always been at its heart an alliance organized against Russian power projection westward.

Was NATO on the verge of invading Russia in the winter and spring of 2022? Certainly Putin did not appear to believe this, nor did the rest of the Kremlin leadership, based on their statements at the time. Their articulated focus at the time was on the ongoing conflict in Ukraine’s Donbas, which, although populated with ethnic Russians, is still Ukraine sovereign territory, not Russia. Ukraine using its military to suppress separatists efforts in the Donbas is by definition an internal Ukrainian matter.

Nor, based on reporting, can we conclude that NATO was or is building up troops in preparation for a NATO invasion of Russia. According to Statista, the total number of US military troops in “former Soviet states” at the end of 2022 is 240.

This aligns with the characterizations given by the Pentagon of US active-duty personnel in Ukraine in November of last year:

The Pentagon has confirmed active-duty U.S. military are deployed inside Ukraine and have “resumed on-site inspections to assess weapon stocks”. This is Air Force Brigadier General Pat Ryder.

Brig. Gen. Pat Ryder: “My understanding is that they would be well far away from any type of front line actions, we are relying on the Ukrainians to do that, we are relying on other partners to do that. … We’ve been very clear there are no combat forces in Ukraine, no U.S. forces conducting combat operations in Ukraine, these are personnel that are assigned to conduct security cooperation and assistance as part of the defense attaché office.”

While the actual purpose and mission of those personnel are can be debated (240 personnel could very easily be a covert operations force), the reported numbers are not of the size needed to plausibly mount any form of sustained attack on Russia proper.

NATO is quite capable of invading Russia. NATO might be quite willing to invade Russia. NATO might even be planning to invade Russia at some point. No one should pretend that is an implausible scenario; it is anything but.

However, there is no substantive basis to presume NATO is going to invade Russia “today”. There is no substantive basis to presume NATO is poised to invade Russia in 2023. The troop strengths in Ukraine and in eastern Europe are simply not being reported in the numbers needed for such an invasion to take place.

There might be an invasion in 2025 or 2026, or perhaps in late 2024, but there is little reason to believe an invasion of Russia will happen in 2023. There was even less reason to suppose an invasion of Russia was about to happen in 2022.

History.com Editors. Germany Launches Operation Barbarossa—the Invasion of Russia | June 22, 1941 | HISTORY. 21 June 2021, https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/germany-launches-operation-barbarossathe-invasion-of-russia.

Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe. The Power Of NATO’s Military. https://shape.nato.int/page11283634/knowing-nato/episodes/the-power-of-natos-military.

Masters, J. What Is NATO? 7 July 2023, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/what-nato.

Council On Foreign Relations. NATO: The World’s Largest Alliance. 17 July 2023, https://world101.cfr.org/understanding-international-system/conflict/nato-worlds-largest-alliance.

NATO. NATO Response Force. 27 July 2023, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_49755.htm.

Masters, J. Why NATO Has Become a Flash Point With Russia in Ukraine. 20 Jan. 2022, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/why-nato-has-become-flash-point-russia-ukraine.

As always, I appreciate your facts and sources...and while reading this, there were all kinds of red flags popping up in my mind about the strategy of the evil people in charge behind the scenes, just waiting for us to deploy the majority of our resources to fight Russia, so that they can give the green light to China to invade Taiwan and have a few other countries melt down in a world War scenario...although I hope that it doesn't happen...it's ripening...ugh!

Well reasoned and sourced. With that said, Russia would like nothing better than to address it's fundamental lack of a land bridge to Kaliningrad. Short of nuclear war, it might come to that, I think this is as fundamental as capturing Crimea.