There is no shortage of optimistic news regarding China’s “rebounding” economy, and its coming contributions to a stagnating global economy mired in recession.

Britain’s The Guardian offers up a stellar example of corporate media cheerleading for China, projecting that China’s economy is “predicted” to power global oil demand through the remainder of 2023.

Global demand for oil this year is on track to rise to a record 101.9m barrels per day as China leads an economic surge among developing nations, the world’s leading energy body has forecast.

The International Energy Agency’s predicted daily average for 2023 is 2m bpd higher than last year’s figure.

This prediction produced a whopping $0.50/bbl in the price of Brent Crude at the time.

Certainly China has the potential to be globally impactful, if its economy is in fact rebounding and recovering from the Zero COVID policies of the past couple of years.

Is its economy rebounding? The data gives a rather muddled picture at best.

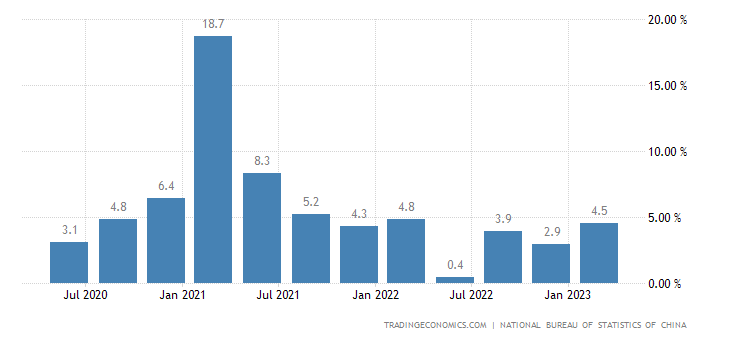

At first glance, China’s economy would seem to be growing significantly, and a “rebound” is very much the right way to describe things. A quarterly GDP growth rate of 2.2% for Q1 of 2023 on its face definitely seems to be how one would anticipate an economic rebound.

On an annualized basis, the reported growth in China’s GDP appears even better, at 4.5%.

Very much in line with China’s just-released Q1 GDP numbers is China’s also just-released monthly retail sales figures, which showed a year on year increase of 10.6%.

Meanwhile, China’s industrial production was reported to have risen by 3.9%—the most since October of last year.

These are without a doubt strong signs of economic growth and recovery. By themselves, they paint a picture of a China economy that is definitely on the rebound and is definitely expanding.

However, we have at least two problems with these economic figures.

The first is that China is notorious for fudging and outright lying about their economic data, and there is more than a little chance that the extremely good news for Q1 of 2023 may be more of the same.

China announced its massive economy grew by 4.5% in the first quarter. It rebounded from the setback created by the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the data from China’s National Bureau of Statistics may be too good to be true.

Recently, Barron’s covered a study from Yale and China’s Fudan University. The conclusion regarding the GDP data was that “the evidence is very clear that the numbers have been manipulated.”

If Beijing is cooking the books, then China’s economy very likely did not grow by an annualized rate of 4.5%, or even a quarterly rate of 2.2%, during Q1 of 2023.

The second problem is that an expanding Chinese economy would almost certainly show up as a significant increase in global demand for oil, and the necessary telltale signs of such an increase are simply not there.

While the production cut announcements by OPEC+ at the end of March did produce a momentary rise in the price of oil, both Brent Crude and West Texas Intermediate, two benchmark oil prices, have largely moved sideways since those initial rises, with declines in recent days eliminating all of last week’s gains..

If we take a longer view of oil prices, we see that even with the recent rises in oil prices, these two benchmark blends failed to break out of a trading band that goes back as much as six months more or less.

China may yet lift global oil demand, but so far in 2023, that demand is not showing up as an upward trend in oil prices. There still is no sustainable upward pressure on oil prices—i.e., there is no sustained increase in global oil demand.

At the same time, China’s coal production is rising.

This correlates well with the increase in electricity production through the end of 2022.

(Note: China’s National Bureau of Statistics does not report January and February data for many metrics).

We must acknowledge that increasing electricity production is consistent with economic growth in China.

However, we must also acknowledge that electricity production in China fell to 71,7292GwH during the month of March from its last reported level of 75,7850GwH.

While March 2023 electricity generation was significantly greater than March 2022—just as December 2022 was a marked improvement over December 2021—the longer term pattern suggests that electricity generation in China will decline over the next couple of months before surging later in the summer

This pattern, much like most of corporate media’s forecasting, promises significant demand increases during the latter half of the year. While that is an optimistic forecast, it is still just a forecast—it is an anticipation of future economic growth, not a reflection of current economic growth.

Moreover, other data is not quite so optimistic.

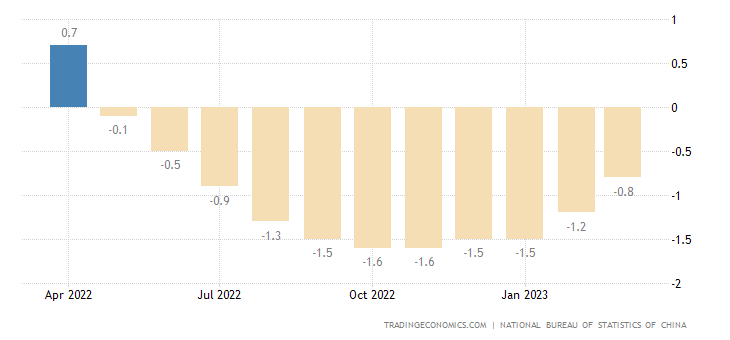

For March, China’s National Bureau of Statistics reported China’s Producer Price Index dropped year on year by 2.5%.

This was the sixth straight monthly decline, and the largest such decline. Just as with consumer price inflation, negative values for the change in the producer price index is more consistent with a cooling and slowing economy, rather than an expanding one.

This decline in producer prices dovetails with recent reports of declining hourly wages in Shenzhen, driven largely by Foxconn’s efforts to slow Apple’s ongoing plans to move more capacity out of China to other countries such as India.

Foxconn Technology Group, Apple’s largest contract manufacturer, has slashed hourly rates for workers at its Shenzhen campus amid a supply chain shift away from China.

The iPhone maker’s facility in China’s southern technology hub was offering rates of 19 to 20 yuan (US$2.76 to US$2.90) per hour this week for smartphone assembly line and component production roles, according to three local hiring agents. This was down from the same period last year, when Foxconn was offering 22 to 26 yuan for the same jobs, according to job posts from agencies.

Falling wages is rarely something that accompanies significant economic expansion.

Additionally, while overall unemployment in China fell last month, youth unemployment has been rising.

Even as China saw its economic engine churn out surprising growth during the year’s first quarter, a rising unemployment rate among young adults offered them little respite in an uneven post-Covid recovery.

It also reflects how authorities must strike a balance when rolling out supportive policies to get China back on its feet following three difficult years of lockdowns and shutdowns.

As with any industrialized economy, China absolutely must put its young people to work in order for there to be any semblance of future economic prosperity. Only labor today can produce wealth tomorrow.

Similarly consistent with economic decline rather than economic expansion, China’s newly built housing price index also declined year on year, for the 11th straight month.

Although the decline was the smallest decline since June of last year, which could indicate housing prices are finding a floor, it is still a significant decline and one which seems poised to extend into next month, which would mean that prices on China’s new homes will have declined year on year for a full year.

This ongoing decline in the housing market is similarly a signal of recession rather than growth. It certainly is not the result one would expect from a “rebounding” economy.

However, not all indicators for the housing market are negative. While year on year housing price changes are negative, month on month figures have been positive for the past three months.

A bottoming out of the housing markets would be a rare bit of good luck for Chinese developers, which have been dealing with the after effects of a deflating property bubble.

It should be noted that Bloomberg is projecting real estate investment in China will fall by 3% this year.

Bloomberg Economics’s base case is for property investment to fall 3% this year compared to 2022. Other economists forecast investment to remain flat or record growth in the low single digits this year — a reversal from last year’s 10% contraction, due to new government policies to support the sector.

Whether housing investment will recover this year is one of the main uncertainties for China’s economy. Real estate investment fell 5.7% in the first two months of the year compared with the same period in 2022, according to official data.

If there is to be a rebound in the Chinese economy, it seems unlikely that it will involve China’s real estate markets.

In that same projection, Bloomberg notes that the 3% figure presumes government interventions to support the housing market. If the government does not intervene China’s GDP growth would become a contraction.

Without any policy response, the downturn would be even more grim: GDP would increase just 1.9% this year, followed by a 0.4% contraction next year, the economists wrote. In that scenario, the property crisis would spill over into global markets. The VIX index would jump 10 points, in line with 2015 when China’s stock market collapse and currency devaluation sent shock waves around the world.

Elsewhere, the South China Morning Post reported that real estate investment in China declined by nearly 6% year on year during Q1.

Investment in property development in China declined in the first quarter of 2023, extending a year-long slump as developers backed off on new-home construction despite a jump in sales, indicating that recovery for the vast and economically crucial market remains fitful.

Property development investment dropped 5.8 per cent year on year to 2.6 trillion yuan (US$377.8 billion) in the first quarter, slightly worse than a 5.7 per cent loss recorded during the first two months, according to data released by the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) on Tuesday. Residential investment was 1,976.7 billion yuan, a decrease of 4.1 per cent.

While China’s housing markets arguably are starting to recover, there is still enough ongoing turmoil within those markets to make robust growth in that economic sector a somewhat less than probable outcome. If China is to experience significant economic growth this year, it is unlikely to come from housing.

What has been growing in China recently is the amount of new debt. Totals for new yuan loans, outstanding yuan loan growth, and total social financing all rose significantly during March.

However, this explosion of new debt is problematic, to say the very least. Debt remains an ongoing concern, with national debt in China growing many times faster than in the United States.

In this line, data acquired by Finbold indicates that as of April 12, China’s national debt amounted to $14.34 trillion, ranking second globally. This value reflects a year-on-year (YoY) increase of $3.81 trillion, or 36.18%, compared to the $10.53 trillion recorded in 2022. The United States, holding the highest national debt globally, has a total of $31.68 trillion, representing a YoY increase of $1.3 trillion or 4.28%, reaching $30.38 trillion. Therefore, China’s national debt has surged almost three times that of the United States in the past 12 months.

One part of China’s overall debt load, the debts owed by local government financing vehicles (LGFV), stands equal to about 48% of GDP.

But there is one more elephant in the room: Borrowings from local government financing vehicles. For years, municipalities have been relying on these off-balance-sheet entities to fund infrastructure and support the local economy. LGFV debt rose to 57 trillion yuan ($8.3 trillion) in 2022, or 48% of China’s gross domestic product, according to estimates from the International Monetary Fund.

Because LGFV debts are so large, and because LFGVs themselves are non-profit (as their purpose is essentially public as opposed to private investment), default risks on what amounts to local government debt is rising, even as yields are not.

Investors are nervous. LGFVs’ ability to service their debt is worse than developers’, in that their mandate is non-profit and to provide public services. The average return on assets among LGFV bonds was only 0.4% in the first half of 2022, according to data compiled from Gavekal Dragonomics. Meanwhile, these 1,800 issuers are not compensating buyers for the risks they take, paying on average only 4.3% interest.

To make matters worse, after the property slump, municipalities may not be in a position to help out their LGFVs even if they wanted to. Before Covid, regional authorities got roughly 20% of their income from land sales. Last year, this important revenue stream tumbled 23%.

So large has the local government debt problem become that some commentators are calling for China to develop a municipal bankruptcy process that would formalize the inevitable debt restructurings many local governments are sure to experience in the relatively near future.

Beijing, meanwhile, has made it clear it will not bail out every local government financing vehicle in a policy known as “every household should look after their own babies”. If local governments are unable to repay debts and Beijing is unlikely to help, it is inevitable that some local governments will go through some form of debt restructuring. In fact, many local governments have already gone through a de facto liquidation process to sell every saleable asset on their hands.

Without any standard procedure or criteria, indebted local governments are scrambling to stay afloat in their own way, and this can in turn hurt business confidence or even affect people’s livelihoods. A much better solution is for China to come up with a proper bankruptcy system.

Yet despite the obvious and growing risks in China’s rising debt pile, Beijing is actively encouraging more debt, more loans, as a means of stimulating the economy—and the reviving property markets in particular.

Mr Zhou Hao, chief economist at Guotai Junan International Holdings, said the authorities need to guide banks to lower mortgage rates significantly to help home buyers and property developers.

The People’s Bank of China (PBOC) unexpectedly lowered the amount of cash banks must keep in reserve in late March, giving lenders more cash to disburse loans.

This need for stimulus borrowing is not at all compatible with a depiction of an energized economy rebounding from Zero COVID.

Is China’s economy really growing? Did it really grow by 2.2% last quarter?

Ultimately, we do not truly know.

Ultimately, it does not really matter.

The real answers—and the real questions—always lie in the details that lurk behind the monolithic headline numbers.

It is within those details that we can see the challenges confronting China, and whether or not how they are responding to those challenges is meeting with any measure of success.

We can tell from Foxconn’s falling wages that the demand for labor is soft, and perhaps softer than is compatible with claimed economic growth of 2.2% for the quarter.

We can tell from declining oil prices that while China’s oil demand might be projected to increase dramatically during the remainder of 2023, it has not yet done so.

We can tell from China’s rising youth unemployment that their demographic challenges have yet to be resolved.

We can tell from China’s encouragement of new home purchases with stimulus and lower interest rates that their real estate markets are still in distress, and that the property bubble is still deflating.

We can tell from China’s rapidly expanding debt load that Beijing is still betting the farm on stimulus measures.

We can tell from all of these things taken together that China’s economic “rebound” is, as has become de rigueur for the media, more a matter of narrative fiction than of empirical fact. We can tell just from the existence of this data that China has more than its share of economic problems

We can tell from this data that if these problems are not resolved, there is a day of reckoning up ahead where the narrative will no longer be of China’s growth but rather of China’s collapse.

Do you think the collapse will be preceded by military action (against Taiwan and/or the U.S.).

You sure don’t see tons of people clamoring to immigrate to China.