The Federal Reserve’s Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) surprised exactly no one when it announced another 25bps increase to the federal funds rate yesterday afternoon.

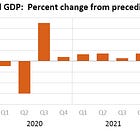

Economic activity expanded at a modest pace in the first quarter. Job gains have been robust in recent months, and the unemployment rate has remained low. Inflation remains elevated.

The U.S. banking system is sound and resilient. Tighter credit conditions for households and businesses are likely to weigh on economic activity, hiring, and inflation. The extent of these effects remains uncertain. The Committee remains highly attentive to inflation risks.

The Committee seeks to achieve maximum employment and inflation at the rate of 2 percent over the longer run. In support of these goals, the Committee decided to raise the target range for the federal funds rate to 5 to 5-1/4 percent. The Committee will closely monitor incoming information and assess the implications for monetary policy. In determining the extent to which additional policy firming may be appropriate to return inflation to 2 percent over time, the Committee will take into account the cumulative tightening of monetary policy, the lags with which monetary policy affects economic activity and inflation, and economic and financial developments. In addition, the Committee will continue reducing its holdings of Treasury securities and agency debt and agency mortgage-backed securities, as described in its previously announced plans. The Committee is strongly committed to returning inflation to its 2 percent objective.

This was exactly what just about everyone expected the Federal Reserve would do.

After its most aggressive interest rate hikes in 40 years, the Federal Reserve on Wednesday is expected to approve a final quarter-point increase and signal a long-awaited pause, economists say.

Now the question becomes “what will break now?” We probably already have some idea—unfortunately.

Suffice it to say, I do not share Jay Powell’s rosy outlook on the economy.

The reality is that the economy barely expanded at all, and that the US economy along with the rest of the world economy is mired in an economic slowdown cum stagflationary recession.

Additionally, as Powell’s prepared statement for the press conference following the announcement illustrates, he is completely misreading the jobs situation.

The labor market remains very tight. Over the first three months of the year, job gains averaged 345,000 jobs per month. The unemployment rate remained very low in March, at 3.5 percent.

He amplified his misunderstanding later on in response to a question involving the Federal Reserve’s “full employment” mandate.

Q: How does the other side of the mandate, the jobs side, once you get from 3 percent, going from 3 to 2, how does the other side of the mandate balance?

MR. POWELL: I think they—you know, they will both matter equally at that point. Right now, you have a labor market that’s still extraordinarily tight. You still got 1.6 job openings, even with lower job openings numbers, for every unemployed person. We do see some evidence of softening in labor market conditions, but overall you’re near a 50-year low in unemployment. Wages—you all will have seen the wage number from late last week, or whenever it was. And, you know, it’s a couple percentage points above what would be—what would be consistent with 2 percent inflation over time.

So we do see some softening. We see new labor supply coming in. These are very positive developments. But the labor market is very, very strong. Whereas inflation is, you know, running high, well above our—well above our goal. And right now, we need to be focusing on bringing inflation down. Fortunately, we’ve been able to do that so far without unemployment going up.

As Powell made clear in his Jackson Hole speech last August, he views the job market as a principal contributor to inflation.

However, the data on that is mixed, as is the Fed’s approach to addressing labor imbalances.

What Powell (and many others) fail to notice is that, despite the high number of job openings, hiring trends have not shifted up or down outside of a relatively steady range since before the pandemic and the 2020 government-ordered recession.

With such a complete misread of the jobs situation, it comes as no surprise that Powell’s policy choices are similarly misdirected.

Yet if Powell’s policy of hiking the federal funds rate will not “correct” the labor imbalances, what will the policy impact?

One thing the rate hike will not do is raise interest rates more broadly. The market has already spoken on that, with only the 3-Month Treasury yield logging any gains yesterday.

The 1-Year, 2-Year, and 10-Year yields all dropped.

Wall Street’s aversion to higher interest rates remains very much intact, the Fed Open Market Committee be damned.

One trend that may be reasonably expected to continue is the rise in the use of the Fed’s overnight reverse repurchase facility, which has become a guaranteed return for most money market funds.

Because the interest paid through the reverse repo window is driven by the federal funds rate, reverse repo operations just became that much more attractive for money market funds.

The reverse repo market is one of the primary reason the country’s banks are hemorrhaging deposits since the Fed’s rate hike strategy began.

While the Fed has been marginally successful in drawing down its balance sheet, bank deposits have declined even more—and we must note that a decline in bank deposits was not an observed phenomenon when Paul Volcker raised the federal funds rates back in the early 1980s.

In fact, the present rate cycle is the first time bank deposits in the aggregate have actually declined.

This is a rather disturbing difference between the Volcker era and today—and is by itself reason for the Fed to take a step back and reconsider what it is doing with its rate hike strategy.

At the very least, we may presume that the decline in bank deposits will continue after today’s rate hike. Even without the reverse repo facility, there are simply too many easy alternatives to bank deposits with vastly greater interest rates—as Apple has proven with widespread adoption of its savings account product since its introduction at the end of April.

The 4.15% return Apple offers on the savings account it floated along with Goldman Sachs Group, Inc. is more than the 3.90% return Goldman offers for its in-house high-yielding savings account under the Marcus consumer brand.

By ignoring the deposit outflows, the Fed is guaranteeing they will continue.

Will the Fed’s rate hikes bring down inflation? Certainly there are those analysts who think so.

Over the last 30+ years, every time Fed Funds (blue) were raised above the levels of core sticky inflation (orange), policy turned out to be restrictive enough to cool inflationary pressures back to 2% or below.

Unfortunately, reliance on this presumed pattern falls victim to the classic logical fallacy post hoc ergo propter hoc—”after this, therefore because of this.” When we look more closely at the trends involving consumer price inflation and the federal funds rate, the asserted correlation quickly becomes questionable.

If we look at various inflation gauges and overlay shifts in the federal funds rate during the Volcker Recessions, we see the federal funds rate was higher than the consumer price inflation rate before the rate hikes.

Simply pushing the rate above the rate of inflation can’t have brought inflation down if the federal funds rate was already above the inflation rate.

If we look at the ten years prior to the Volcker Recessions, we again see the federal funds rate above the rate of inflation even when that rate was increasing.

The view that pushing the federal funds rate above that of consumer price inflation restricts monetary policy enough to push inflation down also fails to account for why inflation didn’t take off when the federal funds rate went below the rate of inflation after the 2008 Great Financial Crisis and related recession.

The influence of the federal funds rate on inflation—regardless of which inflation metric is selected—is simply too problematic to conclude that getting the rate up to a certain level will itself produce a downward pressure on inflation.

This is the fatal flaw in the Federal Reserve strategy for reining in consumer price inflation. The strategy presupposes that raising the federal funds rate will catalyze a series of interest rate rises, which will in turn impact spending, which will in turn impact inflation. This is how Richmond Fed President Tom Barkin summarized the strategy last summer.

Barring an unanticipated event, I see rising rates stabilizing any drift in inflation expectations and in so doing, increasing real interest rates and quieting demand. Companies will slow down their hiring. Revenge spending will settle. Savings will be held a little tighter. At the same time, supply chains will ease; you have to believe chips will get back into cars at some point. That means inflation should come down over time — but it will take time.

Unfortunately for the Fed, the markets have had interest rate ceilings beyond which rates have not risen, thus unraveling the entire strategy.

Without more interest rates rising than just the federal funds rate, goosing the federal funds rate can have no influence on consumer price inflation. Since last November, the federal funds rate has been a problematic tool for pushing interest rates up broadly.

The only thing pushing up the federal funds rate has done reliably is drain deposits from the banking system. This latest federal funds rate hike is likely to continue that process. We have three grim examples of how that ends.

The Federal Reserve is not going to break the back of consumer price inflation with its rate-hike strategy. Instead, it will break the banking system yet again—and again, and again, and again.

And that will lead to "digital money" in which we all will bank with GOOGLE or some similar on-line entity which will be controlled ultimately by China. At least the little "people."

Or, the alternative is Nuclear War.

“But because the human ego is loathe to admit it’s been duped, many patriotic Democrats will continue allowing themselves to be led like sheep into the closing noose of the hammer and sickle. By the time they realize what happened, it will be too late.”

—John Eidson

You make a very persuasive argument for the Fed’s recent policy decisions not working. But now it’s too late, they’re between a rock and a hard place, and as the economy tanks and banks fail, they are going to come under great pressure to ‘fix’ it. I don’t see any good options left for them. Do you see a course that could remedy all the problems, or has that horse not only left the barn but ran screaming down the road?