In hindsight, that Britain’s Labour Party won a landslide victory in the United Kingdom’s latest elections is less remarkable than it might first seem.

From the pig’s breakfast the Tories made of Brexit to the serial hypocrisies of COVID restrictions disregarded by the party leadership, to the horrendous “mini-budget” that made absolutely no sense whatsoever, it would have been a most amazing act of political resurrection had the Conservatives managed to remain in power.

The Labour Party has won a landslide victory in the UK general election, sweeping into power after 14 years of Conservative rule on the back of a wave of public disillusionment.

Party leader Keir Starmer took over as prime minister on Friday after King Charles III formally asked him to form a new government, with the politician promising the British public he would steer the country towards “calmer waters.”

Starmer, 61, begins his term with what is one of the biggest parliamentary majorities in British history and is expected to introduce a program of far-reaching reforms.

We should be cautious about presuming, however, that Labour has a sweeping mandate for root-and-branch reform of the British government. What looks large on the outside becomes considerably smaller upon closer inspection.

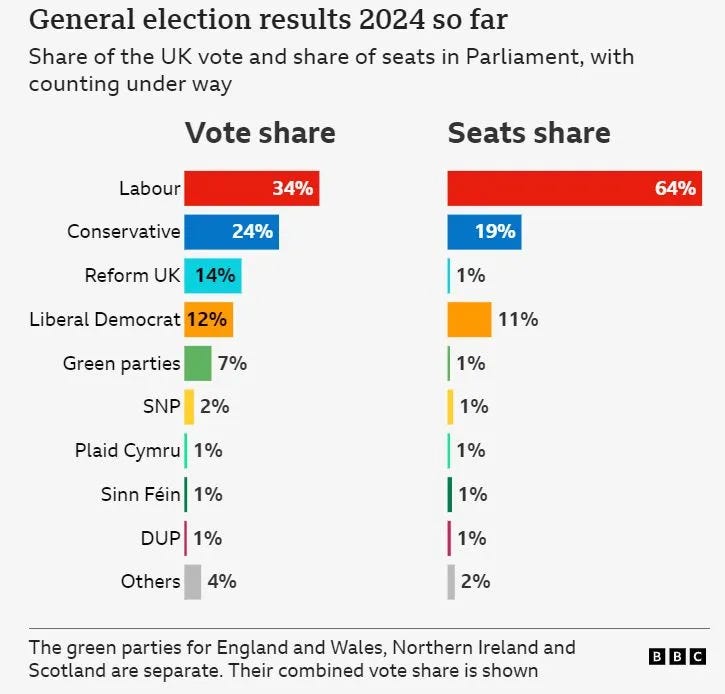

While Labour took an astoninshing majority in the House of Commons, winning 64% of the available seats, Labour’s actual share of the popular vote was little more than half that.

Indeed, if Labour’s election win is a mandate for anything it is a mandate for greater devolution and more localized government within the UK.

Britain gives us yet another reason for keeping government small and highly localized.

Labour won 34% of the popular vote in the UK, yet has 64% of the seats in the House of Commons.

It is not hard to fathom why: at the district level, Britain uses the same “first-pass-the-post” model as the United States. Thus 34% of the popular vote nationwide can “win” 64% of the districts simply by having the most votes in those districts.

Which equates to less of a mandate to govern than the professional political class wants to admit.

Indeed, there is speculation already that Nigel Farage’s insurgent Reform Party played the spoiler in a number of districts by splitting the conservative vote. That is a credible speculation. If the Reform Party votes are combined with the Conservative Party votes, that vote total exceeds what Labour received.

The Conservatives would not be entirely out of bounds to ascribe their election defeat primarily to the presence of the Reform Party.

At the same time, we must remember staggering number of scandals the Conservatives have endured during their long years in charge.

There was Theresa May’s complete inability to put together a comprehensive Brexit agreement for the United Kingdom’s exit from the European Union, having three separate agreements being shot down in Parliament.

Members of Parliament have rejected for a third time Prime Minister Theresa May's Brexit deal, the withdrawal agreement she sealed with the EU to take the UK out of the bloc.

Despite the result being closer than the previous two rejections, MPs still voted it down by 344 to 286, a majority of 58.

The vote came on Friday 29 March - the date originally set for the UK to leave the EU.

That blow came after Ms. May weathered a no-confidence vote by her own party backbenchers the previous year.

Two months after her Brexit negotiations went up in flames, she resigned as Prime Minister.

Mrs May had been struggling to get parliamentary support for the legislation needed to implement the deal she had agreed with the EU on how the UK would leave the bloc.

Her deal was rejected three times by Parliament. Efforts to find a compromise with the opposition Labour Party also failed.

On Tuesday, Mrs May made another attempt to convince members of parliament (MPs) to support her EU Withdrawal Agreement Bill - by offering a vote on whether to hold a second referendum, if the bill was passed.

The offer was designed to attract support from Labour MPs - but enraged many Brexit-supporting Conservatives.

Members of her cabinet began openly opposing the bill, while party members called for her to resign.

Ms. May was followed by the irascible Boris Johnson, whom the media wasted no time in comparing (unfavorably, of course) to Donald Trump.

At a time of polarization and political chaos, the United Kingdom and the United States are about to be led by two remarkably similar figures. On Tuesday, Britain's ruling Conservative Party elected Boris Johnson as their leader by an overwhelming margin, sending him to No. 10 Downing Street. He will take office on Wednesday.

Like Trump, Johnson is a larger-than-life populist who has made controlling immigration and restoring his nation's standing in the world key issues in recent years. (Unlike Trump, he is given to speaking in Latin, making ancient historical allusions and has written a biography of Winston Churchill).

There would be, however, one signature difference: The attacks on Donald Trump time and again proved to be media and Deep State confabulations.

Boris Johnson, on the other hand, was beset with more mundane accusations of corruption.

But after a week in which No. 10 tried to block sanctions against an MP who broke lobbying rules, Westminster insiders and voters alike have begun to ask if this government has finally pushed its carefree approach to the rules too far.

Downing Street was forced into an embarrassing U-turn after opposition parties refused to cooperate in efforts to spare former Cabinet minister Owen Paterson from a proposed 30-day suspension for an “egregious” breach of parliament’s code on paid lobbying.

Paterson himself resigned as an MP after it became clear how badly ministers had misjudged the mood of the public and parliament, but there was near-universal bafflement at how the government had allowed itself to be dragged into the affair in the first place.

Yet if Boris Johnson was corrupt, his short-lived successer Liz Truss was simply inept, as her disastrous “mini-budget” quickly proved.

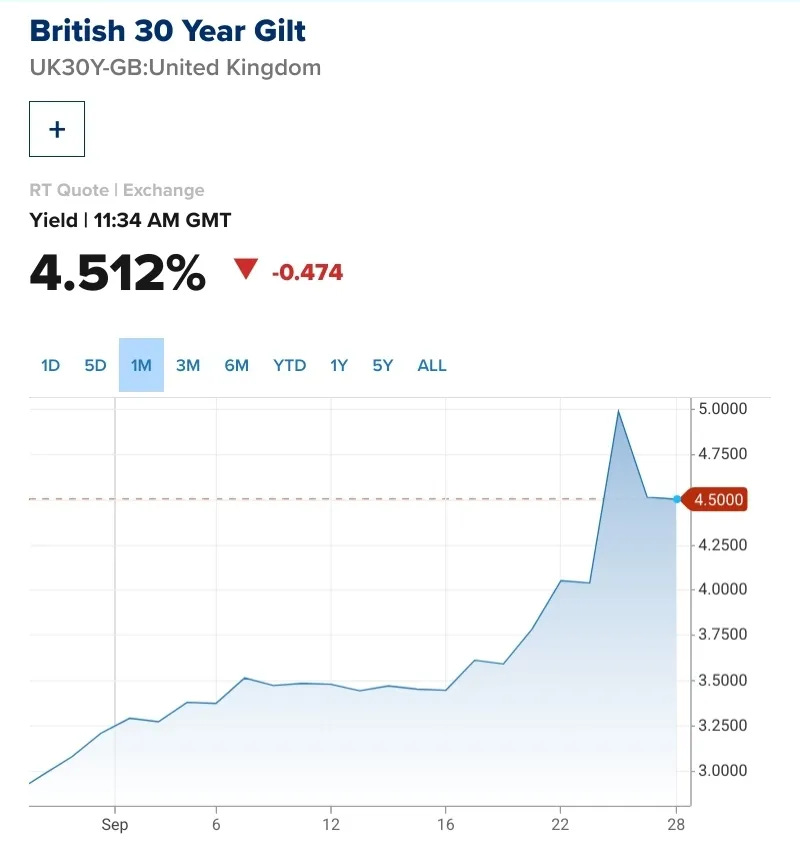

Britain has been through the wringer since September’s mini-budget. Not only was Kwasi Kwarteng’s not-so-mini plan the trigger for a domestic financial crisis and raising mortgage costs for millions, it lit the blue touchpaper for his political downfall and that of his close friend, Liz Truss.

It was all supposed to be so different. Truss had spent the summer promising to cancel the rise in national insurance and corporation tax in the Conservative leadership race. Those pledges, plus the popular energy price freeze, would have been plenty for the new government to announce in the supposedly stripped-back tax and spending event.

How bad was that mini-budget? Bad enough that it very nearly collapsed Britain’s pension funds as yields on long-dated gilts skyrocketed, forcing the Bank of England to intervene directly in the marketplace to stabilize yields and bail out exposed pension funds.

Shortly after that debacle, Liz Truss was gone.

What was not gone were the scandals, as her successor Rishi Sunak would soon find out.

Britain’s ruling Conservatives believed the ethics scandals which dogged Boris Johnson’s premiership would finally be consigned to the history books when they ousted him as leader last year.

It hasn’t quite turned out that way.

The investigation announced on Monday into the tax affairs of Conservative Party Chairman Nadhim Zahawi followed a series of damaging allegations about the historic conduct of senior ministers in Rishi Sunak’s administration which have left Tory MPs fearing further public backlash.

Indeed, the serial corruption scandals seemed to be a repeat of those which brought down the Conservatives the last time, after Margaret Thatcher’s long tenure at 10 Downing Street.

“It’s got the feel of a 1997 defeat coming,” they said, in a reference to Tony Blair’s historic Labour victory over Conservative John Major after a series of revelations about corruption and misconduct among Tory MPs.

Indeed, looking back to the 1990s is unlikely to provide much reassurance for Sunak’s party. Like Sunak, Major had pledged to root out sleaze in the party, but voters decided they wanted rid of him anyway.

Are the Conservatives headed into the political wilderness for the foreseeable future?

Possibly—or possibly not.

At least one media commentator in Britain is of the opinion that Labour’s Keir Starmer is not likely to be any better than the Conservatives, and might even be worse.

How is he likely to govern? A former lawyer with a bland rhetorical style and a tendency to modify his policies, Mr. Starmer is accused by critics on the left and right alike of lacking conviction. He is labeled an enigma, a man who stands for nothing, with no plans and no principles. His election manifesto, which The Telegraph hailed as “the dullest on record,” appears to confirm the sense that he is a void and that the character of his administration defies prediction.

But a closer look at Mr. Starmer’s back story belies this narrative. His politics are, in fact, relatively coherent and consistent. Their cardinal feature is loyalty to the British state. In practice, this often means coming down hard on those who threaten it. Throughout his legal and political career, Mr. Starmer has displayed a deeply authoritarian impulse, acting on behalf of the powerful. He is now set to carry that instinct into government. The implications for Britain — a country in need of renewal, not retrenchment — are dire.

While Starmer has promised root-and-branch reform, only time will tell if he can deliver.

We should recall that the Democrat control of Congress and the White House lasted but two years, from 2009 through 2010. For all the hype and hope of the Democrats ushering in a new era of progressive dominance, they completely failed to achieve any lasting realignment of the electorate.

Finally, something must be said about the electorate that produced these results. According to national exit polls, 2010 voters broke almost evenly in terms of their 2008 presidential votes; indeed, given the normal tendency of voters to "misremember" past ballots as being in favor of the winner, this may have been an electorate that would have made John McCain president by a significant margin. Voters under 30 dropped from 18 percent of the electorate to 11 percent; African Americans from 13 percent to 10 percent, and Hispanics from 9 percent to 8 percent. Meanwhile, voters over 65, the one age category carried by John McCain, increased from 16 percent of the electorate to 23 percent.

These are all normal midterm numbers. But because of the unusual alignment of voters by age and race in 2008, they produced a very different outcome, independently of any changes in public opinion. Indeed, sorting out the "structural" from the "discretionary" factors in 2008-2010 trends will be one of the most important tasks of post-election analysis, since the 2012 electorate will be much closer to that of 2008. That's also true of the factor we will hear most about in post-election talk: the "swing" of independents from favoring Obama decisively in 2008 to favoring Republicans decisively this year. Are these the same people (short answer: not as much as you'd think), or a significantly different group of voters who happened to self-identify as independents and turned out to vote?

Starmer will have to display an uncommon vision of British governance if he is to prevent the Labour Party from suffering a similarly short tenure at 10 Downing Street.

What the Labour Party win does tell us is that voters everwhere are increasingly fed up with the status quo within their governments. The perception that those who govern are increasingly out of touch with their constituents is the common theme that connects the UK’s embrace of left-wing Labour and France’s cozying up to Marine LePen and the French far-right.

While France has one of the world’s biggest economies and is an important diplomatic and military power, many French voters are struggling with inflation and low incomes and a sense that they are being left behind by globalization.

Le Pen’s party, which blames immigration for many of France’s problems, has tapped into that voter frustration and built a nationwide support network, notably in small towns and farming communities that see Macron and the Paris political class as out of touch.

Such a global political trend is what perhaps should give Democrats their greatest concern over Joe Biden’s most recent (and most embarrasing) display of dementia. While the media is having the expected feeding frenzy over Biden’s obvious infirmities, as we saw on Wednesday, when a slew of Democrat governors met with Biden at the White House and emerged to give him a vote of confidence.

But let us remember also that Biden's cognitive decline is nothing new. For many of us, the newsworthy part of Biden's debate collapse was that corporate media found it newsworthy after having dismissed so many earlier exemplars of his declining mental health. For many of us, Biden's clear cognitive deficits have been part of every political issue during his term.

Biden’s dementia—which has now been conceded by even the White House staff—makes every issue that much worse for Joe Biden. Biden’s dementia makes him appear un-Presidential on every issue.

Let us also remember that, regardless of Biden's obvious infirmities, the Democrats do not have a clear alternative available.

Consequently, not much has actually changed. Biden had an historically bad debate with Donald Trump, and everyone knows it. The Democrats are probably screwed going into the November election—bigly.

Don't assume that impacts what the Democrats believe.

The one thing that absolutely gives Donald Trump his greatest credibility as a Presidential candidate is Joe Biden’s demonstrable unfitness for the Oval Office. Biden’s obvious infirmity all at once magnifies all of his Administration’s policy shortcomings while confirming even for the non-partisan voter the magnitude of political corruption at work in the Democrats’ now-failed “lawfare” strategy to prevent Donald Trump from even participating in the election.

Biden’s dementia is proof of the absolute corruption and mendacity of his administration.

This is the political backdrop against which the Democrats must not only prevail against Donald Trump but also somehow craft a credible mandate to govern this country for another four years.

If voter sentiment in the US mirrors that of voter sentiment in the UK and voter sentiment in France, the Democrats are well and truly screwed—bigly.

The reality for the Democrats is there may be no stopping the train wreck that appears to be happening within Joe Biden’s campaign for re-election.

If that is the case, Donald Trump will return to the Oval Office next January—for better or worse.

Very true.

It's not a vote for Labour but a vote for change, and with First Past the Post there was no other choice.

What a wealth of interesting insights here! The MSM today has trumpeted the Labour Party’s win as if it was confirmation that the American voters would likewise vote towards the Left this year. Of course, Peter shows us the data proving that no, the Conservatives lost more because of votes lost to the Reform Party than votes lost to Labour.

I would love to hear more about Farage in future posts, Peter. It’s difficult for people in one country to understand the politics in another; we lack cultural and historical context to interpret correctly. So I’m wondering if Farage is heading up a political movement more similar to Le Pen’s, or to MAGA, or to something unique to Great Britain. Is the Reform Party surging in growth, or just a disenchanted blip? Please keep us posted, especially before America’s Election. Trends in Europe can be harbingers of cultural and political shifts here at home, as you well know. Thanks!