Central Banks Keep Raising Rates, Inflation Keeps Not Responding

Reality Is Winning Over Theory. Again

The Bank of England has joined the European Central Bank and the Federal Reserve in raising key interest rates 25bps yet again, in a neverending bid to quash high consumer price inflation.

The Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) sets monetary policy to meet the 2% inflation target, and in a way that helps to sustain growth and employment. At its meeting ending on 10 May 2023, the MPC voted by a majority of 7–2 to increase Bank Rate by 0.25 percentage points, to 4.5%. Two members preferred to maintain Bank Rate at 4.25%.

Once again, the “prevailing wisdom” is that raising interest rates will tighten monetary policy, which will bring down inflation.

Yet the BoE has raised its Bank Rate 12 times and the UK’s inflation rate is among the highest in Europe.

Do interest rates curtail inflation or not?

Despite the prevailing wisdom, the data suggests the answer is “not”—at least, not directly and not exclusively. When we look at the data for the US and the Federal Reserve, the relationship between interest rates and inflation quickly gets murky and imprecise. Yet understanding this relationship is essential if one is to properly gauge whether central banks are either timely or appropriate in their interest rate manipulations.

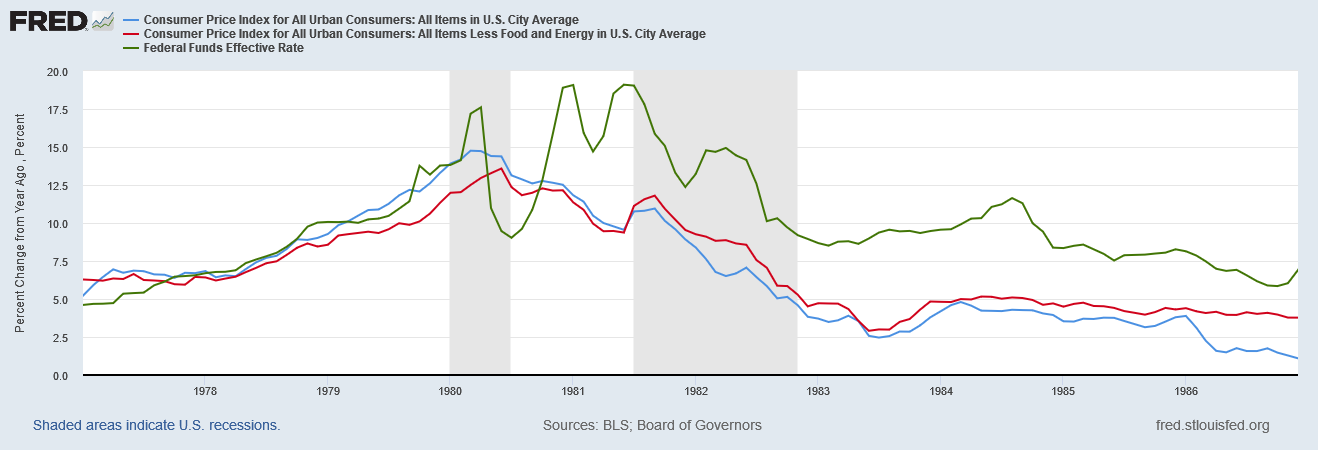

A direct albeit imprecise relationship is discernible between bank rates such as the BoE Bank Rate and the Federal Reserve’s Federal Funds Rate and inflation rises and falls. We can see that just by looking at the US CPI data vs the Federal Funds rate.

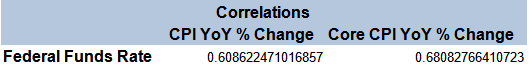

When we calculate the correlation coefficients, we find that there is a substantial correlation, although with ample room for other influences as well.

However, there is a distinct problem with this correlation—it is a positive correlation. The prevailing wisdom says the relationship is an inverse one.

Overall, interest rates and the rate of inflation in an economy usually have what we like to call an ‘inverse’ relationship. Summer Raye, a business journalist at Britstudent and Write My X, noted, “For the most part, when interest rates are particularly low, the economy will grow. This is because people will borrow more money, there will be more economic activity, and the economy will grow and expand over this period of time.” However, when interest rates are high, people (and businesses) will stop borrowing and choose to save money, meaning economic activity as a whole will take a nosedive. Because of this principle, inflation will decrease when interest rates are high, and increase when they are low; and this is all due to the fact that interest rates are a big influence on economic activity. The Federal Reserve has in the past used this inverse relationship as a crude tool to dampen inflation after they have increased the money supply. The FED does this by raising the aforementioned FED Funds Rate.

Nor is this merely the provincial view of specialty blogs and newsletters. Time Magazine advances largely the same thesis on interest rates vs inflation.

Why does the Fed increase interest rates?

In short, the Fed hopes its rate hikes will temper demand for consumer goods and services by making it more expensive to borrow money.

The philosophy is that if goods and services become too pricey, less people will buy them, and sellers will have to lower their prices to retain customers. For example, a car dealership may be forced to slash the price on a new car if potential buyers are unwilling to pay the extra interest rates for auto loans.

Again, if businesses cut prices because people are limited in their spending by curtailed credit, the result is an inverse relationship, which the data clearly does not show.

Moreover, if we zero in on a particular decade—e.g., the one from 1977 through 1986 bracketing Volcker’s battle with inflation—we see the correlation is very strong at first, and then breaks down during the Volcker Recessions.

We are still seeing, however, a direct relationship and not an inverse relationship.

Overall, the correlation in the decade surrounding the Volcker Recessions is weaker between the federal funds rate and the year on year percent change in the Consumer Price Index across the entire timespan.

If we look at the period between 1977 and 1979, the correlation is extremely strong.

This would seem to suggest that raising interest rates actually causes inflation—a complete negation of the prevailing wisdom. The alternative interpretation is that rising inflation pushes the federal funds rate higher, which makes the prevailing wisdom entirely irrelevant, as it casts inflation as the driver of the federal funds rate, which would undermine its utility as a driver of inflation or inflation reduction.

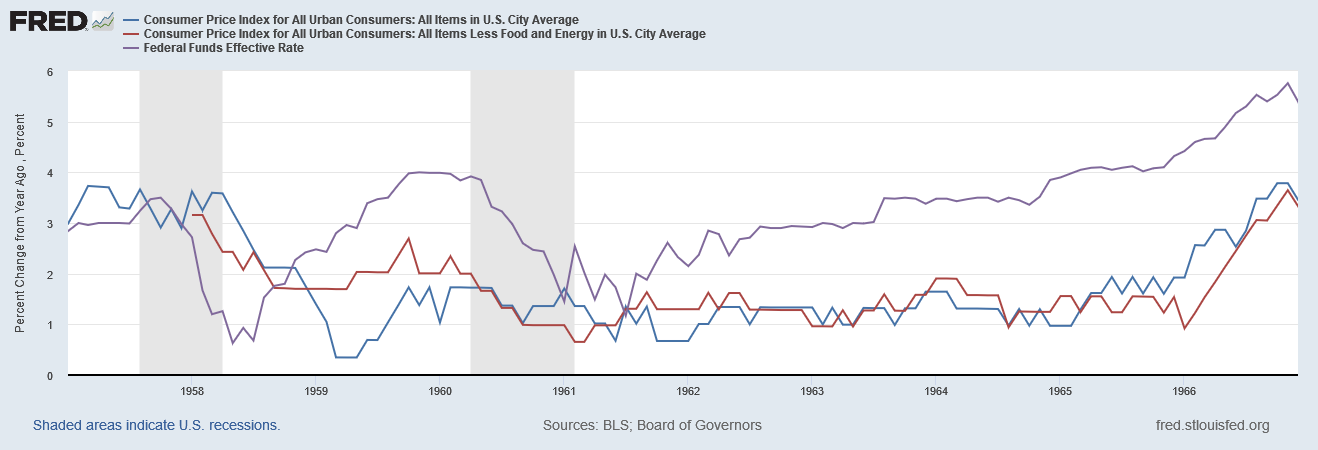

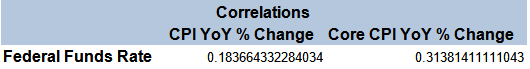

When we examine the previous decade, 1957-1966, we see a very weak direct relationship between the Federal Funds Rate and consumer price inflation.

This is confirmed when we look at the correlation coefficients for this period.

Either the “prevailing wisdom” is wrong, or we have wrongly stated that prevailing wisdom. The lack of a strong inverse correlation does not admit of any other possibility.

If we venture away from media sites, however, we begin to see a slightly different depiction of the relationship between interest rates and inflation. For example, Investopedia describes the relationship thus1:

Inflation and interest rates tend to move in the same direction because interest rates are the primary tool used by the Federal Reserve, the U.S. central bank, to manage inflation.

Going by this explanation, while rising inflation rates generally prompt the Fed to raise the federal funds rate, the timing and the degree of that increase are entirely arbitrary decisions by the Federal Open Market Committee. This sets up a circular set of expectations, in which inflation is acknowledged as an indirect driver of the federal funds rate, which in turn presumably exerts increasing downward pressure on inflation the higher it goes.

However, the expectation that an increased federal funds rate would exert downward pressure on inflation necessarily implies that, at some point, the effective relationship between the federal funds rate and inflation beomces an inverse one: the higher the federal funds rate goes, the lower inflation should go. Even if that relationship is not constantly present, there should be a rate level where the federal funds rate does become a downward driver on inflation.

Yet, looking again at the CPI and federal funds rate data over time, that is not at all what is presented.

As the correlation coefficients prove, there is a weak to moderate direct relationship between inflation and the federal funds rate. There is not an inverse relationship between the two either displayed or reliably calculated—in some periods the correlation coefficients are weakly negative and inother periods they are weakly or moderately positive. At no point does the data point conclusively to a level of the federal funds rate above which it forces inflation to be lower.

If anything, inflation is more likely a driver of the federal funds rate at all levels—as inflation moves higher the federal funds rate moves higher, and as inflation moderates, so, too, does the federal funds rate. If that is the relationship between inflation and the federal funds rate then the federal funds rate is completely meaningless as a tool for controlling inflation.

Former Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke in 2004 offered up this explanation of why we are seeing a weak direct and not inverse relationship between the federal funds rate and inflation2:

The current funds rate imperfectly measures policy stimulus because the most important economic decisions, such as a family's decision to buy a new home or a firm's decision to acquire new capital goods, depend much more on longer-term interest rates, such as mortgage rates and corporate bond rates, than on the federal funds rate. Long-term rates, in turn, depend primarily not on the current funds rate but on how financial market participants expect the funds rate and other short-term rates to evolve over time. For example, if financial market participants anticipate that future short-term rates will be relatively high, they will usually bid up long-term yields as well; if long-term yields did not rise, then investors would expect to earn a higher return by rolling over short-term investments and consequently would decline to hold the existing supply of long-term bonds. Likewise, if market participants expect future short-term rates to be low, then long-term yields will also tend to be low, all else being equal. Monetary policy makers can affect private-sector expectations through their actions and statements, but the need to think about such things significantly complicates the policymakers' task (Bernanke, 2004). In short, if the economy is like a car, then it is a car whose speed at a particular moment depends not on the pressure on the accelerator at that moment but rather on the expected average pressure on the accelerator over the rest of the trip--not a vehicle for inexperienced drivers, I should think.

In other words, the relationship between the federal funds rate and the rate of inflation is highly problematic—exactly as the data shows. Setting the federal funds rate is as much about managing inflation expectations as it is about directly inhibiting the rise of consumer price inflation. The Federal Reserve tweaks with interest rates as much to persuade people something is being done about inflation as to actually influence consumer price inflation trends.

The role of sentiment in both understanding and predicting economic activity (including inflation changes) is a significant but often underappreciated one.

This is a primary reason why it is important to note how Wall Street reacts to the actions and commentaries of the Federal Reserve, as well as to note the various metrics of Main Street sentiment (e.g., the University of Michigan Survey of Consumer Sentiment). What people think and feel about their economic condition is a primary driver of future economic behavior.

The role of sentiment is also crucial in understanding how Paul Volcker’s efforts to constrain money supply growth in the early ‘80s were and still are viewed as successful even though they failed completely. Volcker’s view of how to combat inflation was simple: slow money supply growth by hiking interest rates3.

“By emphasizing the supply of reserves and constraining the growth of the money supply through the reserve mechanism, we think we can get firmer control over the growth in money supply in a shorter period of time,” Volcker told the assembled reporters. “But the other side of the coin is in supplying the reserve in that manner, the daily rate in the market…is apt to fluctuate over a wider range than had been the practice in recent years” (Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis 1979a).

As a result of the new focus and the restrictive targets set for the money supply, the federal funds rate reached a record high of 20 percent in late 1980. Inflation peaked at 11.6 percent in March of the same year. Meanwhile, the new policy was also pushing the economy into a severe recession where, amid high interest rates, the jobless rate continued to rise and businesses experienced liquidity problems. Volcker had warned that such an outcome was possible soon after the October 6, 1979, FOMC meeting, telling an ABC News program that “some difficult adjustments may lie ahead,” (Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis 1979b). With the economy now facing a recession, it is perhaps not surprising that the Fed came under widespread public criticism.

Ironically, by pushing this strategy Volcker was guilty of what Milton Friedman termed the “interest rate fallacy”—that higher interest rates presume tighter monetary policy4.

After the U.S. experience during the Great Depression, and after inflation and rising interest rates in the 1970s and disinflation and falling interest rates in the 1980s, I thought the fallacy of identifying tight money with high interest rates and easy money with low interest rates was dead. Apparently, old fallacies never die.

A quick survey of both M1 and M2 money supply growth vs the federal funds rate shows that high rates do not automatically mean low growth and low rates do not automatically mean high growth.

Volcker fed the American public a line of BS and got away with it. He persuaded people to have different expectations about where inflation was headed next. He succeeded in shifting Americans’ inflation expectations, and that shift in sentiment helped bring inflation back under control.

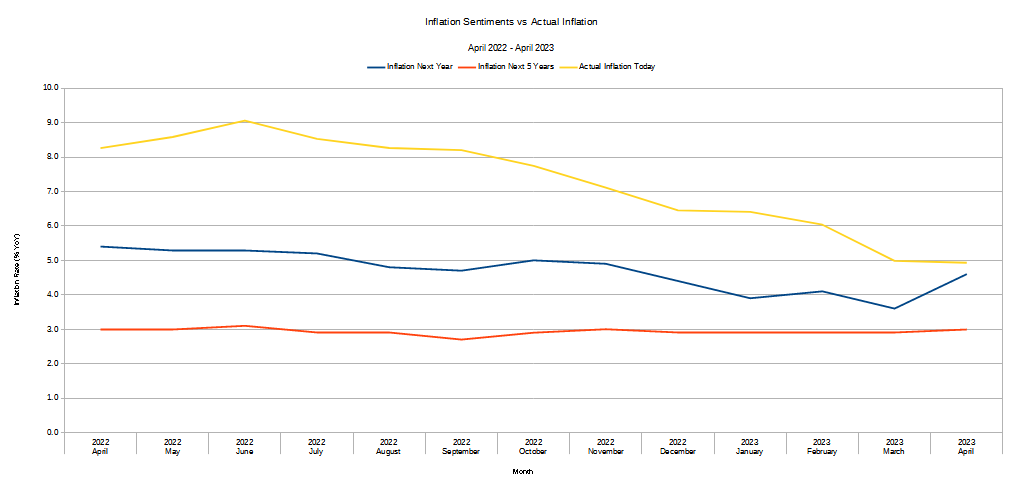

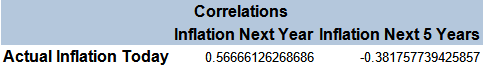

That role of Main Street sentiment is relevant even today. When we compare current inflation expectations as surveyed by the University of Michigan with the observed rates of inflation exhibited in the Consumer Price Index, we see a reasonably strong correlation between near term inflation expectations and actual observed inflation today.

The correlation coefficients confirm this relationship—and even show it to be stronger than the relationship between inflation and the federal funds rate.

University of Michigan economist Richard Curtin terms this confluence of expectations and outcomes on inflation “inflationary psychology”—and speculates that it is a powerful inflation driver.

This situation has been termed “inflationary psychology.” Consumers purposely advance their purchases in order to beat anticipated future price increases. Firms readily pass along higher costs to consumers, including the future cost increases that they anticipate. That’s what happened in the last inflationary age, which started in 1965 and ended in 1982: Expected inflation became a self-fulfilling prophecy. Many commentaries assert that the current situation is nothing like the situation faced in 1978-80. That’s true, but irrelevant. The more apt comparison would be to the five to ten years prior to that period, when inflation had not yet reached crisis levels. Government officials claimed they had the policy tools that could easily reverse inflation, just as they claim now.

Curtin concludes that an “aggressive” policy works because it reshapes these expectations and defuses the self-fulfilling aspects of inflationary psychology.

Much more aggressive policy moves against inflation may arouse some controversy. Nonetheless, they are needed. Adam Smith’s legendary invisible hand describes how individuals acting in their own self-interest can create unintended benefits for the entire society. Unfortunately, the country now faces the potential for an inflationary hand that can transform self-interested decisions into losses for the entire economy.

Following this logic, Volcker’s rate hikes in the early ‘80s “worked” not because they directly tamped down inflation or restrained money supply growth—the data shows they did neither—but because they proved to a cynical public that the Fed was “serious” about restraining money supply growth and tamping down inflation, and thus moderated their own inflation expectations, which in turn moderated inflation.

Volcker’s Kabuki theater over inflation “worked” simply because Volcker succeeded in making people believe it would work.

By the same token, Powell’s Kabuki theater over inflation is not working because people aren’t believing him—I certainly do not believe him!

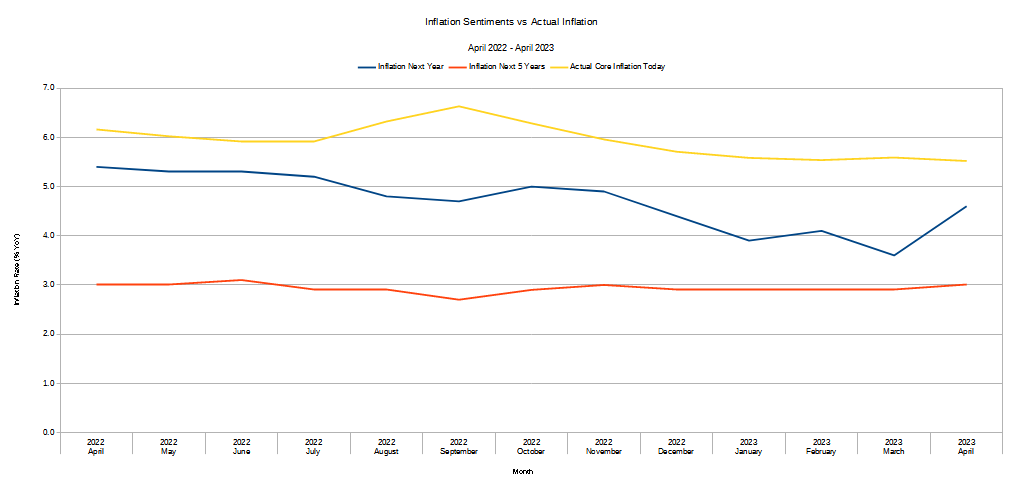

Part of Powell’s credibility problem may stem from the intractable nature of core consumer price inflation, which in addition to being less than responsive to the Federal Reserve’s interest rate manipulations is also less responsive to consumer expctations, as the UMich consumer sentiment data shows.

The influence of consumer expectations is noticeably weaker over core inflation than over headline inflation rates. Again correlation coeeficients bear this out.

It is quite possible that the intractability of core inflation has begun shaping consumer sentiment to expect more rather than less inflation. The recent uptick towards expecting higher inflation rather than lower inflation certainly suggest that.

This confluence of expectation and outcomes also serves to illuminate the unpleasant reality that more consumers are living paycheck to paycheck today than in the recent past.

While this is undoubtedly a reflection in part of higher prices due to inflation, it is still an expression of the reality that people are spending more of their income—more or less up to their entire income—and saving less. Without assessing the precise cause-and-effect dynamic, we may safely conclude that much.

The simple reality of consumer spending that the increase among consumers living paycheck to paycheck in the US aligns well with recent consumer price inflation increases.

Thus we see a primary reason why central banks are failing to bring inflation under control: people do not believe them. Whether that lack of credibility is a belief that they are not serious about resolving high consumer price inflation or a belief that their methods will not work, or perhaps even that their methods will favor the few and disfavor the many, the end result is the same: central bankers are not being taken seriously.

Paul Volcker was taken seriously by both Wall Street and Main Street. Jay Powell is not taken seriously by either Wall Street or Main Street. The ECB’s Christine Lagarde is not taken seriously.

When Andrew Bailey of the Bank of England prattles on about the need to “stay the course”, I for one certainly do not take him seriously!

Central bankers everywhere have manipulated and mismanaged their respective remits to the point where they are simply no longer credible figures. Whether one regards them as malign actors in furtherance of a hidden agenda or simply inept incompetents greatly overmatched by the tasks they have been given, the prevailing sentiment worldwide is that whatever central bankers say is likely at odds with reality.

No longer can they get away with pushing the interest rate string and trust that consumers will be persuaded by their show of “effort” enough to moderate their spending and thus cool inflation down for them. That message is just not adequate any more.

With neither facts and data nor credibility on their side, central bankers and their pet theories about how inflation can be contained are being repeatedly gobsmacked by the reality of a consuming public that no longer believes them or the things they say.

This is always how it goes: whenever theory stands at odds with reality, reality wins. Every time.

Folger, J. “What Is the Relationship Between Inflation and Interest Rates?”, Investopedia. 5 May 2022, https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/12/inflation-interest-rate-relationship.asp.

Bernanke, B. “The Logic of Monetary Policy.” 2 Dec. 2004, https://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/speeches/2004/20041202/default.htm. Remarks by Governor Ben S. Bernanke Before the National Economists Club, Washington, D.C.

Medley, B. Volcker’s Announcement of Anti-Inflation Measures. 22 Nov. 2013, https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/anti-inflation-measures.

Friedman, M. “Reviving Japan.” Hoover Digest, Apr. 1998, https://www.hoover.org/research/reviving-japan. Reprinted from the Wall Street Journal, December 17, 1997, from an article entitled "Rx for Japan: Back to the Future."