Officially, China’s economy is well on the way to recovery. Prices are stable, employment was stable, and production is improving.

This is quite literally the CCP’s official narrative for the Chinese economy as of November 2023.

In November, under the strong leadership of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CPC) with Comrade Xi Jinping at its core, all regions and departments strictly implemented the decisions and arrangements made by the CPC Central Committee and the State Council, adhered to the general principle of pursuing progress while ensuring stability, and fully and faithfully applied the new development philosophy on all fronts. All regions and departments accelerated efforts to foster a new development pattern, took solid steps to promote high-quality development, endeavored to expand domestic demand, optimize structure, boost confidence and fend off risks. As a result, the macro-control policies continued to show effects, production and supply increased steadily, market demands kept improving, employment and prices were generally stable, people’s well-being was robustly and effectively guaranteed, transformation and upgrades were advanced solidly, and the national economy further consolidated its good momentum of recovering and turning for the better.

How lucky the Chinese people are to have such perceptive and agile stewards of the Chinese economy watching over them!

Oh…wait…we must look also at the data—those pesky facts again.

When we do look at the data, this little narrative of the CCP starts to look more than a little delusional. Prices are only stable because they are stagnant, and employment is stable because no improvement on unemployment has been realized in the past few months (and we no longer know the true state of youth unemployment as Beijing declines to release those numbers).

The narrative says growth. The data says not. Which one do you think I am going to trust first even from China? Which one should you trust?

How bad is China’s data? On the surface, not that bad. Industrial production did rise 6.6% year on year, the largest increase since February of 2022, per China’s National Bureau of Statistics.

While the NBS Composite Purchasing Manager’s Index (PMI) edged down in November, it remained above 50 (expansion territory).

Fixed Asset Investment did grow by 2.9% for the second month in a row, according to the NBS data.

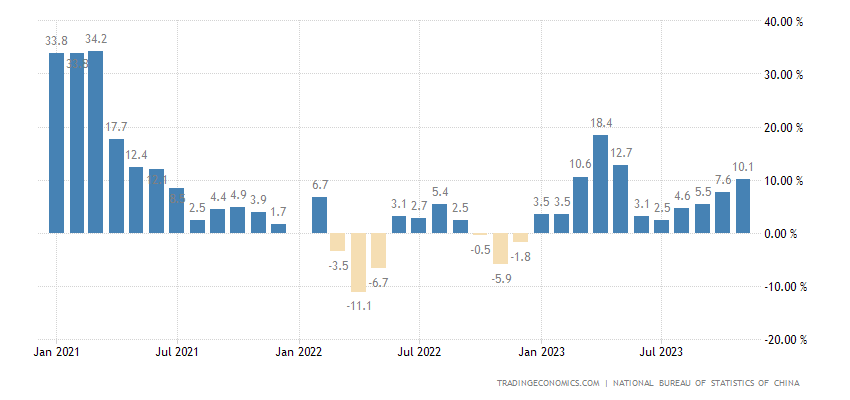

Retail Sales printed a 10.1% increase year on year in November, 2.5 percentage points higher than October per the NBS.

Broadly speaking, these are good numbers. Where is the problem?

One of the major caveats we must apply to these nominally good numbers is one of context. Last year China was just emerging from the horrors of Zero COVID, which had a suppressive effect on consumption as well as a lot of industrial production. Posting large gains from that low threshold is not exactly a challenge, as was noted last week in the Wall Street Journal:

But the headline numbers for industrial and retail sales growth—which shot up to 6.6% and 10.1%, respectively—are heavily distorted by comparison with last November, when China’s Covid-19 lockdowns became much worse. On a month-on-month, seasonally adjusted basis, retail sales actually declined slightly, for the first time since July.

That’s right, month on month retail sales are actually down for November.

Additionally housing prices are still in decline, with November being their fourth straight month in the negative.

Falling housing prices is hardly a sign of a robust economy, particularly one with as large a real estate sector as China’s.

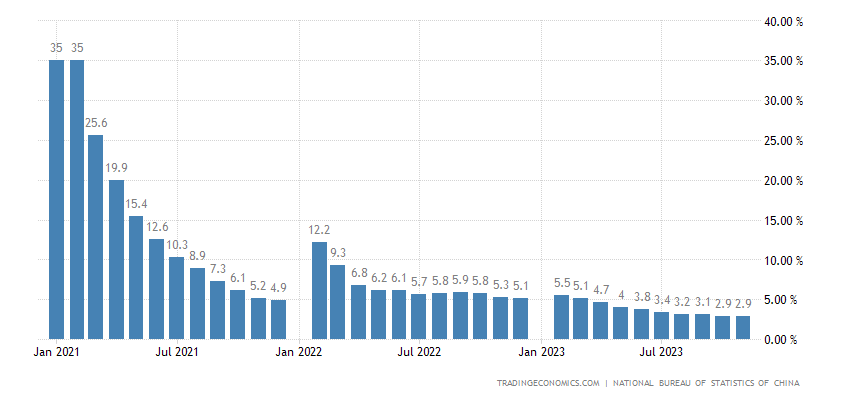

Moreover, China’s “stable” unemployment is still at 5%—there has been no improvement in the official number per the NBS in three months.

For context, China’s lowest unemployment rate post COVID was 4.9% in the fall of 2021. If anything, this is an indicator China’s unemployment rate has bottomed out and may very well rise in coming months.

It also bears noting that China is still suppressing its youth unemployment data, which it last reported in June when it had risen to an eye-popping 21.3%.

At best we may infer that youth unemployment has not improved significantly if at all since that last report.

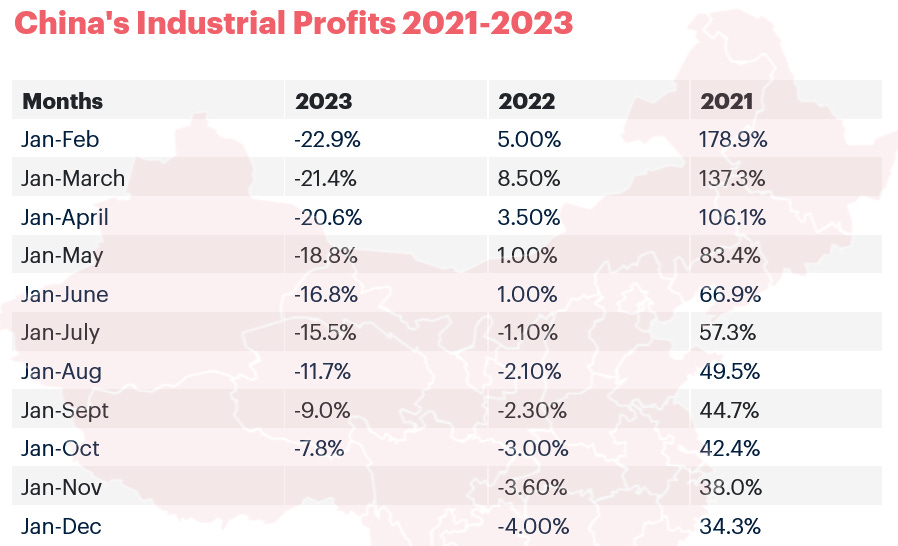

More telling is the sobering reality that China’s businesses have been posting declining profits all year, and for a good part of 2022 as well.

Shrinking corporate profits cut very much against the grain of a narrative of economic growth. Economic growth implies larger profits, not smaller ones. With profits shrinking since July of 2022, the clear implication is that China’s economy has been contracting for about that long.

As much as Beijing wants to put out a positive economic narrative, the official data keeps getting in the way. So apparent are the deficiencies in the data that even corporate media is finding itself unable to overlook them, as well as most China analysts.

“This data indicates that China’s economy clearly slowed down in the fourth quarter,” said Larry Hu, chief China economist at Macquarie Capital.

“The downturn in property and the private investment did not surprise the market – after all, this is the core headwind Beijing is facing.”

Regardless of how Beijing wants to spin the numbers, the reality of the property investment data is that monthly investment in real estate has been declining since June of 2021.

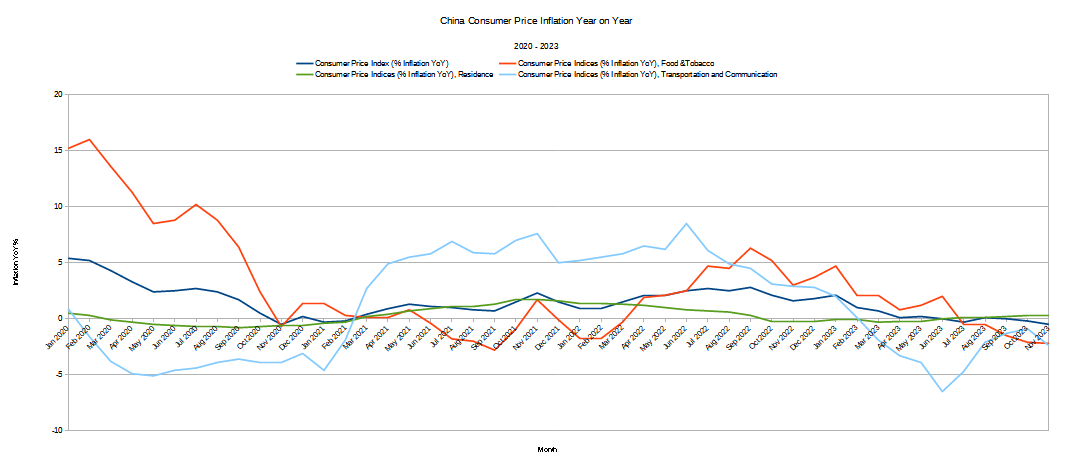

While Beijing wants to spin China’s consumer prices as “stable”, the reality is “deflation”.

In general, and in key areas such as housing, food, and transportation, consumer prices in China have been on the decline since June of 2022.

The month on month percentage declines confirm that prices have been declining broadly since then, and the deflation has spread across sectors during that time.

So drawn out has been the deflation that even the year on year data is printing negative.

While consumers generally apprehend falling prices as a good thing—everyone rationally will choose to pay less rather than more—extended periods of deflation are at least as detrimental to an economy as extended periods of inflation. Deflation distorts demand and can directly suppress demand, as consumers are incented to save and postpone consumption in anticipation of even lower prices later.

This is a particular problem for China, which desperately needs much greater levels of domestic consumption to compensate for declining exports, yet even Beijing’s central economic planners, which met recently to figure out how to goose the economy in 2024, are struggling to find ways to increase domestic consumption.

The meeting, which was hosted by President Xi Jinping, was more “pro-growth” than in previous years, said Larry Hu, chief China economist at Macquarie Group.

With a more “proactive” tone, policymakers may set “4.5-5%” or “around 5%” as the GDP growth target for next year, Hu said, broadly similar to the goal for 2023.

But other analysts questioned whether this level of growth could be achieved without stimulus measures directly targeting consumers, which was not mentioned.

“[There was] no hint for massive consumption support policies,” Citi analysts said Wednesday. “There was no detailed discussion on increasing household income.”

The world’s second largest economy is facing deepening troubles, with weak consumption a major drag.

When even the normally supine corporate media is willing to disregard China’s official economic narrative to this degree, one has to conclude that China’s economy is in very deep trouble!

We do well to remember that a great many China “experts” as well as the corporate media have often genuflected to China as the “coming” economic and geopolitical superpower. Some of them still are willing to do that, talking rather fatuously about China’s “rise”.

Napoleon warned that China was a sleeping giant and the world would shake when it awoke. It has, and accommodating its rise is one this era’s central challenges.

Given the realities of the data, such perspectives by western financial analysts are simply pro-China propaganda, and are about as useful. At present, China is not rising but receding. Despite Beijing’s claims, the data shows the economy is on many fronts contracting rather than expanding. While China’s population could be a global economic force nonpareil, the reality of China’s low per-capita GDP figures are a structural impediment to greatly expanded domestic consumption.

While China as a country is widely regarded as having the 2nd largest economy in the world based on Gross Domestic Product, because of its large population on a per-capita basis China is well off the pace, ranking 63rd in the world according to the World Bank. For comparison, on a per-capita basis the United States is ranked seventh in the world.

When the individual consumer does not have a lot of money, the individual consumer is not going to be doing a lot of consuming. There is no getting around that economic reality.

This also makes deflation an even bigger problem for China than it would be for some other countries. Deflation’s structural disincentives for individual consumers to consume, multiplied by China’s large population, translates into a significant barrier to increasing consumption.

While official data should always be taken with a grain of salt, especially where China is concerned, there is no escaping that China’s official economic metrics according to their own National Bureau of Statistics paints the Chinese economy in a very bad state. Even if China was massaging the data (and at least some entities within China may very well be doing just that), we can plausibly presume that any fudging of the economic data would be slanted towards making the economy appear stronger rather than weaker. We may therefore with confidence apprehend China’s official data as a “best case”. The reality may be worse than the official data shows, but it is unlikely to be any better.

Such are the limits of government narratives even for totalitarian regimes nominally in command of everything. Just as Canute could not command the tides, neither can the most authoritarian governments on earth command economic realities. Despite what Beijing may say about China’s economy, the data is telling a far different—and far gloomier picture.

Despite the optimism of Beijing’s official narrative on the economy, the world’s number two economy is mired in deflation and stagnation, and is declining rather than expanding. Because China is the world’s number two economy, that does not bode well for the global economy as a whole.

The world is heading into recession, and right now China is leading the way.

You’ve got the data, Mr. Kust, and Beijing’s got nothing but obvious propaganda!

Did you see my comment, around a week ago, about how the ‘lying flat’ phenomenon of China’s youth has evolved to be known as ‘let it rot’? Somewhere around 22% of China’s youth (according to the Wall Street Journal’s article) are dropping out, with many throwing parties to celebrate their decision to ‘let it rot’. To me, this is the most ominous signal of all that China is headed for a long, hard economic stretch.

We’ve seen this scenario before, with the rotting and eventual implosion of the Soviet Union. All through the seventies and eighties, the top dogs in the USSR spouted propaganda about how wonderful and constantly improving life was in their Glorious State. Meanwhile, the alcoholism rate among Soviet males kept soaring - that was their version of ‘let it rot’. It did not end well for their economy.

I remember reading an article in Wired magazine, around twenty years ago, about how business was actually conducted in China. Virtually no one trusted the government, so a Chinese citizen looking to get ahead in life turned to his ‘clan’. There are, as I remember, around twenty major clans who had effectively divided up the business realms amongst themselves. If your clan happened to be the one with the unofficial business ‘leadership’ in Shanghai, or Malaysia, or wherever, then you’d pledge your allegiance to your clan and they would take care of you - so long as you were loyal to the clan’s interests and leaders! It all works along the lines of a Mafia, with plenty of bribes, kickbacks, and graft. You’re kept safe so long as you adhere to your clan’s wishes. This is not a utopia that will inspire youth’s dreams and idealism - the options of an oppressive and corrupt government or a Mafia-like business world. What a choice; no wonder the young want to drop out.

They have a tolerable quality of life, with an apartment and adequate food, but they have little to look forward to and little personal freedom within the ‘system’. It’s very hard to *quantify* the yearning for freedom, the ache for an inspiring world, and the excitement of working toward your dreams, so it’s hard to get *facts* about this. But it’s still *reality*, and China is going to be kicked hard by it!