As I wrote last Friday, China is caught in an economic Catch-22: its economy desperately needs stimulus measures to ward off the pernicious effects of structural deflation, and its economy needs a stable yuan to sustain its export economy.

It turns out it managed to get neither.

After fighting for months to keep the yuan stable, Beijing was finally forced to bow to the inevitable and allow the yuan to depreciate further against the dollar.

Chinese authorities have kept the yuan in a vise-like grip for four months, but now signs are emerging that they are ready to allow the currency to weaken.

The onshore yuan on Friday slipped beyond the 7.20 per dollar line that had mostly held since November. The decline sent ripple effects across Asian markets, accelerating losses in some regional currencies and weighing on sentiment toward China-linked assets.

And by “depreciate”, I really mean “crash”. After Beijing gave up the ghost on the yuan China’s currency plunged to its lowest level against the dollar in four months.

This was not the outcome Beijing wanted. Based on currency and money flows within the Middle Kingdom, Beijing has been doing everything it could to prevent this outcome, and it could not do enough.

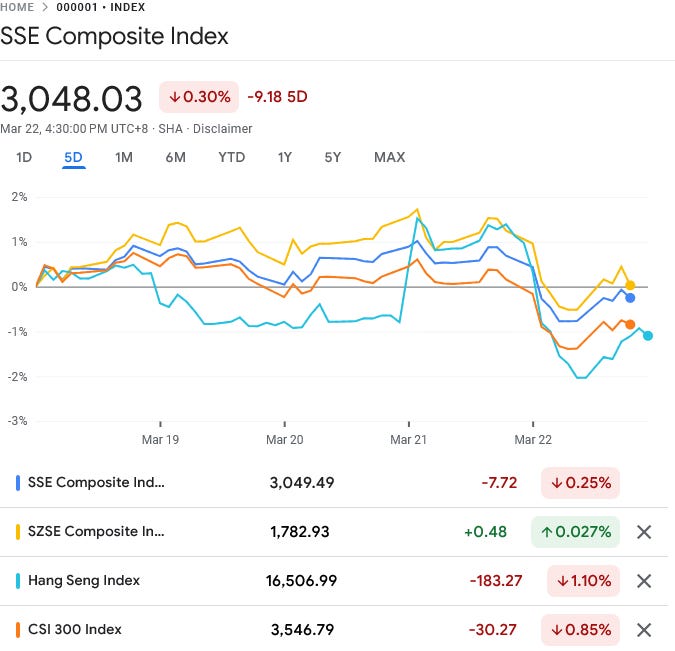

What is noteworthy about Friday’s yuan collapse is that it came after Beijing apparently mounted a mostly successful intervention in Chinese stock markets. In the same period when the PBOC was not giving out any hints of stimulus, the stock market actually managed to stay above water.

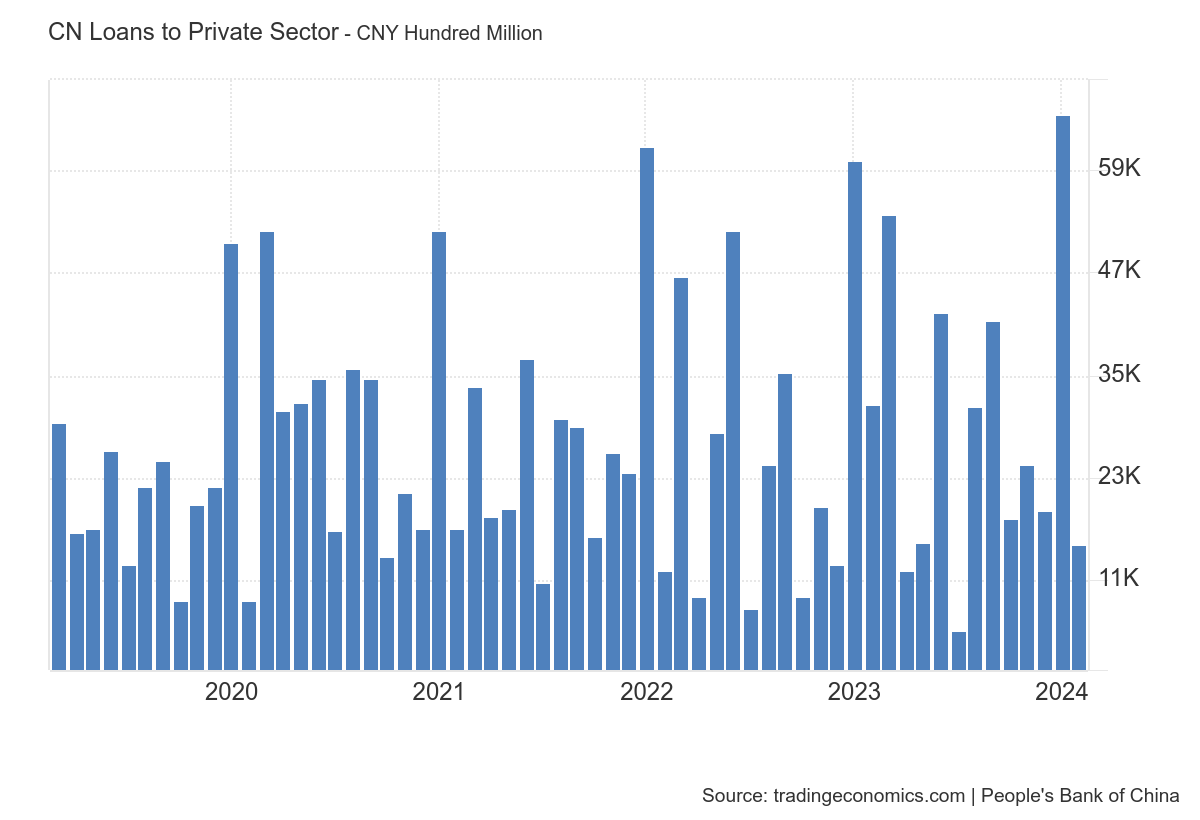

There may be a reason for this. At a time when net new yuan loans are down, loans to China’s non-banking financial institutions when through the roof.

Net new yuan bank loans to China’s nonbanking financial institutions in February surged to the highest level since July 2015, a sign that some of the loans could have been used by state-backed investors to prop up the stock market, according to analysts.

The loans reached 404.5 billion yuan ($56.9 billion) last month, more than 23 times the amount in February 2023 and the highest since July 2015, when the reading was 886.4 billion yuan, central bank data show. In contrast, net new yuan loans in total in February dropped almost 20% year-on-year.

Historically, when this happens, Beijing is funneling money to select institutions to plow it back into the stock market to prevent a market meltdown.

In both February 2024 and July 2015, government-backed companies increased their holdings of stocks and equity-focused mutual funds in a bid to lift the stock market out of a slump, suggesting that state-buying could explain the spikes in new nonbanking loans, analysts said.

“Historical data show that the only time that new yuan loans to nonbanking financial institutions showed a sharp increase similar to that in February was in July 2015, when China Securities Finance Corp. Ltd. (CSF) expanded financing to boost stock market liquidity,” Guotai Junan Securities Co. Ltd. analysts wrote in a recent report, estimating that similar activities supported the increase in nonbanking loans in February.

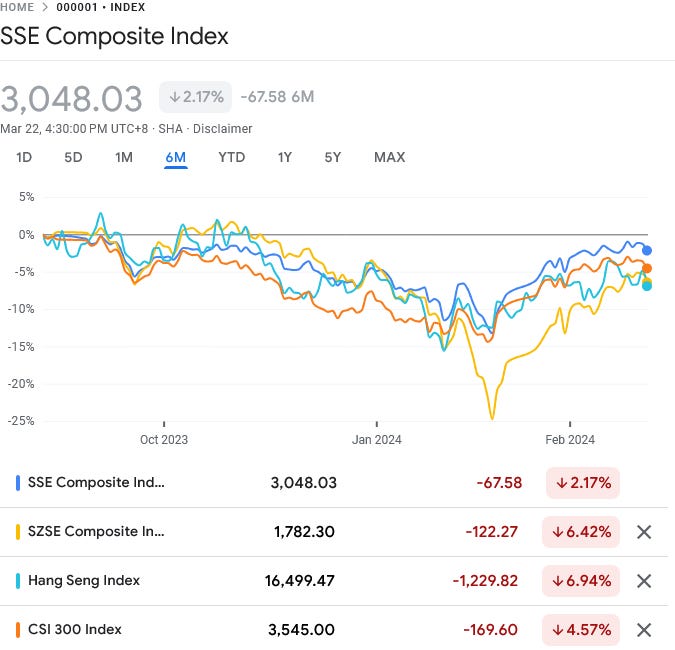

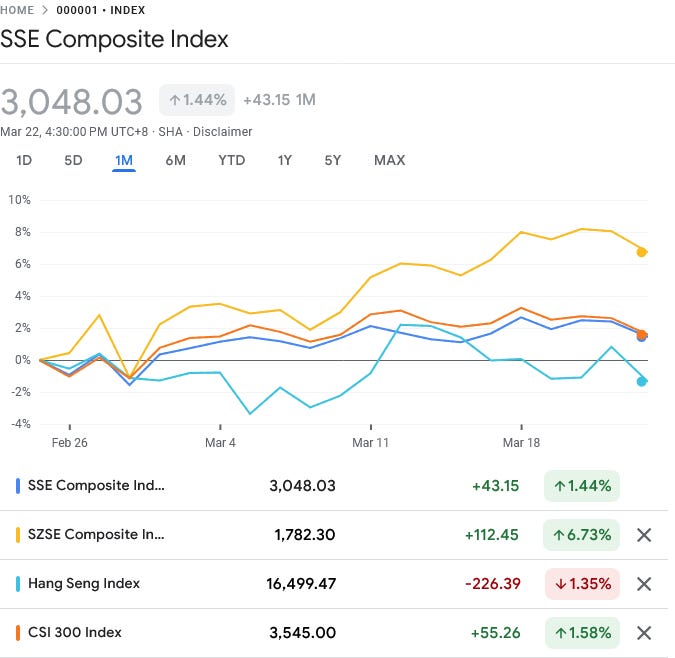

Why did Beijing do this? One reason may be that, at the beginning of the year, the SZSE Composit index collapsed, only to stage a miraculous comeback through last Firday.

All China’s indices had a bad start to the year, but the SZSE had a spectacularly bad time of it. Then it recovered throughout February, not just regaining the lost ground the others had done but all the ground that it had lost relative to China’s other indices.

The result? The SZSE index outperformed the others by several multiples.

However, Beijing’s support came at a price.

While loans to non-banking financial institutions soared, loans to other types of entities collapsed. On the surface, the People’s Bank of China’s decisions to tighten the money supply played a primary role in this.

One possible consequence of the PBOC’s dichotomous moves is arguably a decrease in new yuan loan growth. In February new yuan loan growth printed at a level below that of February 2023.

While there is historically a significant drop off in new yuan loan growth between January and February in any given year, that this year’s drop off left new yuan loans printing below there they were a year ago means that corporate media is likely correct that this is a sign of the Chinese economy contracting even further.

The story is even more stark when one considers China’s level of total social financing, which posted an even steeper drop month on month than new yuan loan growth

While year on year loans to the private sector are still up significantly, February’s drop off compared to January’s stellar increase is a pretty dramatic and not very welcome turnaround.

However, the non-bank financial institution data suggests there was more at play than just a tighter money supply.

Yet even if the data is being read correctly, that Beijing ordered a massive stock market intervention, it may also prove to be the case that, between draining liquidity from the banking system while directing loans for the purpose of propping up the stock market, Beijing managed to squelch its own efforts to stimulate the economy with more credit impulse.

The cruelest irony of all, however, is that Beijing’s interventions in the stock market are the sort of intrusion into the market place which forex traders tend to reward by bidding the currency down—and they most assuredly bid the yuan down against the dollar on Friday, by a massive margin.

So rapidly did the yuan fall on Friday that several state banks were obliged to step in and sell dollars to buy yuan in an effort to staunch the bleeding.

Market sources told Reuters that state banks stepped in subsequently to buy the yuan for dollars. The yuan was at 7.2251 by midday, 257 pips softer than the previous late session close.

What triggered the yuan’s fall? Potentially, a series of small monetary dominoes falling.

The drop in new yuan loans overall (potentially catalyzed by the direction of record amounts of yuan loans to non-bank financial entities) began a whisper campaign coming out of the PBOC that bank reserve requirements were about to be cut in order to stimulate more new yuan loans. Trimming reserve requirements is one way a central bank can increase the pace of money creation. When that rumor began floating around forex markets, traders dumped the yuan, sending it into freefall against the dollar.

While Bejing was successful at stabilizing the yuan after losing roughly half a percentage point against the dollar, the question remains: can the PBOC even think about reducing the reserve requirement?

If the PBOC does not dare reduce the reserve requirement under the circumstances, what becomes of efforts to stimulate loan growth and thus stimulate the economy?

Once again, Beijing is caught in a Catch-22. It can defend the yuan, or it can pump up the stock markets and the economy. It cannot do both.

If it intervenes in the markets, it risks further yuan depreciation. If it defends the yuan, it cannot intervene in the markets, risking further market declines.

To make matters even worse, China has been defending the yuan through policy measures for the past four months—and arguably pursuing monetary policies that are contraindicated for an economy in deflation—and yet the yuan still dropped. The end result is both economic and currency deterioration.

China managed to get the worst of both alternatives, and yet is unlikely to be able to alter that any time soon. The drop in the yuan is almost sure to force Beijing to restrain its stimulus efforts in order to restabilize the yuan at the new lower equilibrium level.

Perversely, restraining the stimulus measures may force Beijing to direct more loans to non-bank financial institutions in order to intervene still more in the stock markets, further distorting loan growth in China, pushing the PBOC to trim reserve requirements, which in turn will push state banks to sell more dollars to defend the yuan.

It is becoming more and more probable that Beijing no longer has any good options for revitalizing the Chinese economy. Every move Beijing might make triggers another unwanted response, forcing Beijing to take a contrarian move that only exacerbates economic conditions.

Only time will tell how long this unenviable downward spiral can continue in China, but the longer it goes on, the less likely it is that China will be able to salvage its economy and pull out in time to avoid complete economic chaos.

https://www.theepochtimes.com/china/foreign-direct-investment-in-china-shrinks-nearly-20-percent-5613673?utm_source=ref_share&utm_campaign=copy

https://www.theepochtimes.com/china/local-government-debt-in-china-soars-to-crisis-levels-5613697?utm_source=ref_share&utm_campaign=copy

Peter, you are a genius in your ability to fully comprehend all of these convoluted financial mechanisms. Me, I’m left with questions. I’ll restrain myself to three.

First, how significant is the RATE of the yuan’s drop on Friday? That is, is this steep and rapid drop going to be seen by world financial markets as a signal to ‘panic’, or are fluctuations of this size and rate normal enough to financiers that they will conduct business as usual?

Secondly, it sounds as though everything Beijing has done to prop up their stock market is artificial- not based at all in market forces of voluntary buy and sell. So, how long do you think this ‘propping up’ can be sustained - months, years, or no historical basis on which to guess?

Thirdly - and you may have no data on which to base an answer for this one - how aware are the average Chinese citizens of the seriousness of this financial decline? Every culture has its quirks that only a native can understand, so I’m hoping that in your research you have encountered Chinese cultural experts who have commented on the average Chinese person’s comprehension of what is unfolding. I’m wondering how ‘clueless’ the culture is, or if they are secretly preparing themselves toward a huge change.

You are priceless, Peter. Thank you!