Counter-Narratives: Why The Sunny Optimistic Market Propaganda Is Wrong

Beware Of Narrow Perspectives And Unchecked Assumptions

Readers of this Substack know I have been asserting the US economy is already in recession for quite some time, and that high inflation diminishes actual economic output, making inflation an indicator of recession, not growth.

However, the preferred narratives as propagated by the corporate media cling to the same “the economy is strong” thesis loved by the Federal Reserve, so that even notional media “outsiders”—putatively independent bloggers and analysts—are pushing this thesis, which media portals such as “RealClearMarkets” then promote alongside the corporate media. While it is intuitively obvious that I disagree with these other media voices, it is important to critically examine their arguments now and again to understand why I do not share their view of things.

Are Retail Sales Doing Well?

Fisher Investments is one of the non-corporate media regulars on RealClearMarkets, and one that is definitely drinking the “economy is strong” KoolAid. Beyond their authorship of the analysis piece to which I am directly rebutting here, I have no direct knowledge of the firm and no interest or agenda beyond rebutting just this one analytical piece.

The particular focus of their analysis is the current trend for retail sales in this country, reported monthly by the corporate media, which to them is justification for a resumption of the “bull market” in stocks.

Retail sales resumed growing in August, following July’s (downwardly revised) -0.4% month-over-month slide with a 0.3% rise.[i] That rise was subject to big positive skew from autos and big negative skew from gas stations—both influenced mainly by price movements. But those canceled each other out, as retail sales excluding autos and gas stations also rose 0.3% m/m.[ii] Headline retail sales also rose 9.1% y/y, which—as many noted—outpaced August’s year-over-year inflation rate, implying sales continue to eke out some growth on an inflation-adjusted basis.[iii] Mind you, that is overly simplistic considering properly deflating retail sales would require squaring up the month-over-month sales growth and inflation rates in dozens of small categories, but the observation is interesting all the same.

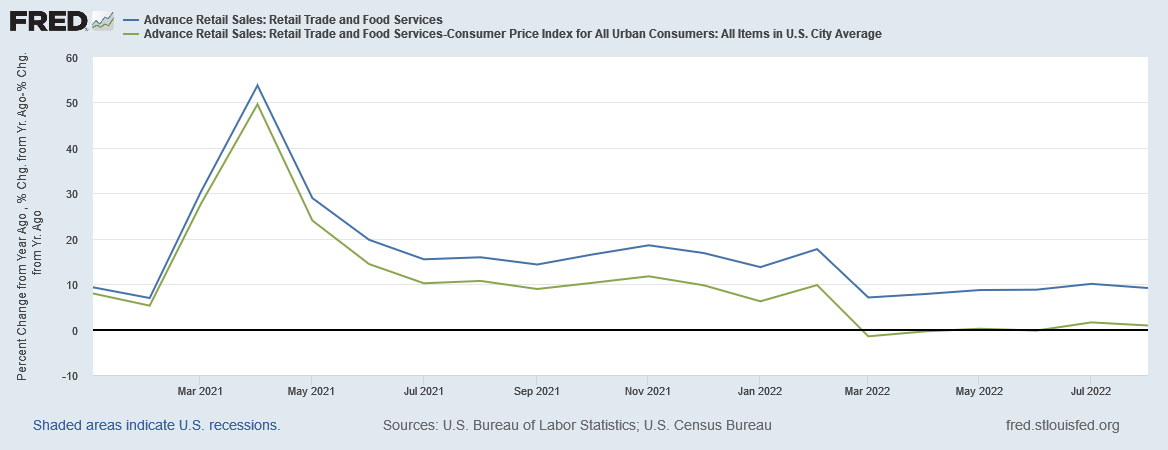

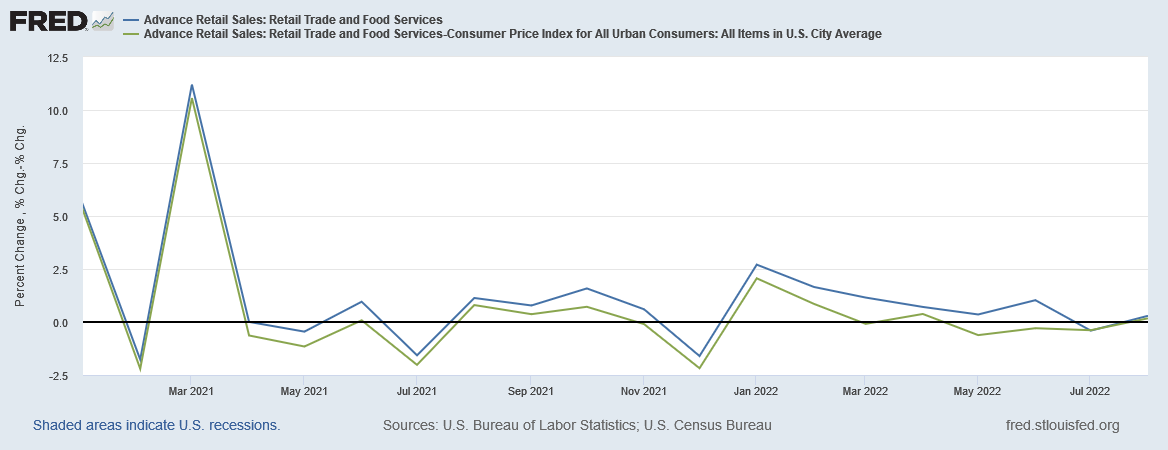

While their key facts on retail sales are notionally true, the failure to include the impact of ongoing inflation is an egregious omission. If one subtracts out inflation, retail sales have seen approximately zero year on year growth since March of this year, as inflation has taken a larger and larger bite of inflation out of the retail sales figure.

Even month on month, inflation has eliminated any retail sales gains from March onward.

Refusing to incorporate inflation effects into an analysis of retail sales is simply naive and unrealistic. Worse, Fisher Investments actually implies that inflation isn’t impacting retail sales in discussing the August numbers.

Not because it was a cheerful observation—rather, in typical pessimism-of-disbelief fashion, most of Thursday’s commentary didn’t offer positive reasons why inflation wouldn’t be eroding spending on goods and food service. Articles didn’t tout strong demand, nor did they express relief that falling gas prices are freeing up more of people’s money for discretionary spending. Rather, much of the coverage centered on timing: Not only is August back-to-school month, which boosts sales of clothing and school supplies, but it is also typically when stores will slash prices in order to make room for holiday season inventory. Accordingly, pundits credited deep discounting for sales’ seeming resilience, implying that the only reason consumers are buying more is that they are raiding clearance sales in order to pinch pennies.

Turning apparent sales growth over the past six months into zero growth is most assuredly an erosion in actual spending. People are not buying more, merely paying more, and the data clearly illustrates that.

This glaring omission reduces this “analysis” to yet more media propaganda pretending that everything is hunky dory in the US economy.

About Inflation

That inflation is solely an issue of money and nothing else has become an almost religious principle among many economists, and Scott Grannis, retired Chief Economist from Western Asset Management is no exception, who ignores all exogenous supply shocks and lays the whole of the rise in inflation at the feet of a profligate federal government.

Above all, I can't emphasize enough that this inflation flare-up was not caused by a Fed policy error: it was caused by the federal government's attempt to soften the blow of Covid lockdowns with massive, deficit-financed transfer payments that inflated the money supply. That mistake ended over a year ago, and M2 money supply growth has since decelerated significantly. So the fundamental reason for our current inflation has long since begun to fade in importance.

The data, however, does not support this thesis even a little. To the extent that the raw data (not seasonally adjusted) shows any trend at all, deficit spending by the Federal government has largely declined since July of 2020, while inflation has increased.

If government deficits were driving inflation, an increase in inflation should correlate to an increase in deficits, not a decrease.

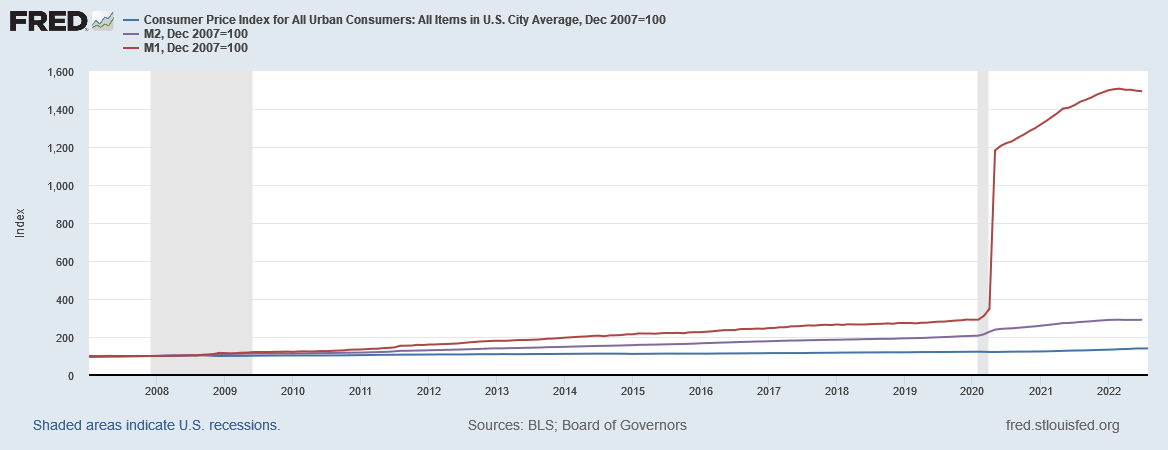

This is further reiterated by the lack of clear correlation between the growth of the money supply and the rise of inflation. While the Fed greatly expanded the M1 money supply in early 2020, inflation did not show up at a meaningful level until the following year, and kept rising even as the rate of money supply growth returned to prior historical levels.

Moreover, if we index the Consumer Price Index, the M1 money supply, and the M2 money supply to the onset of the 2007-2009 recession, to view simply the magnitude of changes in each, we do not see any corresponding shifts in the CPI to match the 2020 increase in the M1.

This is not to say that federal deficits are not a problem, nor that money supply growth is devoid of inflationary pressures, but rather to point out that the relationships reflexively claimed by the “experts” between deficit spending and inflation, or money supply growth and inflation, in the current situation simply are not there. Neither deficits alone nor money supply growth alone can suffice as an explanation for the current trend of rising year on year consumer price inflation.

This lack of demonstrable correlation between inflation and both federal deficits and money supply growth moots the entirety of Scott Grannis’ analysis, and reduces it also to mere media propaganda, propaganda that ignores very real potential inflationary pressures lying ahead.

Understanding Economic Performance Requires Data, Not Narrative.

When a narrative’s key assumptions are not backed by supporting evidence, that narrative must be viewed with suspicion. That is true in economics just as it is true in any other field of intellectual endeavor (e.g., public health policy and epidemiology).

We do not have to presume that deficit spending has no influence on inflation to acknowledge that the data points to another primary cause for rising consumer prices since early 2021. We should not pretend that rising inflation does not distort and ultimately erode retail sales even as nominal numbers rise.

To understand what is unfolding within the US economy, as well as the overall world economy, we should look at the data, at all the data, and see what relationships are demonstrably there as well as the expected relationships that are not demonstrably there. Only then can we be in a position to translate knowledge of the data to an understanding of what actually is happening, not what prior theory and “prevailing wisdom” argues should be happening.

When theory fails to measure up to reality, always go with reality until theory is able to catch up.

One should expect something of a lag after a big pile of money is borrowed into existence (spring of 2020) before it affects prices. 12-18 months strikes me as about right.

Of course the spending spree by the FedGov is by no means the only thing that has contributed to the inflationary pressures we're seeing now. There are still plenty of supply-chain issues, and in a relatively free market, when things are in short supply, goods go to the highest bidder. My own business has paid 5-10 times the normal price for certain semiconductors from the secondary market on a couple of occasions. We didn't like it very much, but it beat the alternative, which would have been to tell our own customers that we have no finished product available for them. I've not raised my prices, but I think I'll likely have no choice early next year.