Factory Gate Inflation Eases, But Not Enough

Future Inflation May Slow, But Not Enough To Allow The Fed Their Cherished Rate Cuts

Is there a glimmer of hope that inflation will ease soon?

Possibly. The Producer Price Index for March printed significantly less inflation than for February.

The Producer Price Index for final demand rose 0.2 percent in March, seasonally adjusted, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today. Final demand prices moved up 0.6 percent in February and 0.4 percent in January. (See table A.) On an unadjusted basis, the index for final demand increased 2.1 percent for the 12 months ended in March, the largest advance since rising 2.3 percent for the 12 months ended April 2023.

The March increase in the index for final demand is attributable to a 0.3-percent rise in prices for final demand services. In contrast, the index for final demand goods edged down 0.1 percent.

The sharp drop in factory gate price rises month on month does suggest that future consumer price inflation may be about to ease—remember, the Producer Price Index is largely seen as a precursor to the Consumer Price Index, and inflationary trends in the PPI are frequently reflected in the CPI after a few months.

What will please the Wall Street “experts” and their cheerleaders in corporate media is that the year on year inflation rate came in below their forecast.

The Labor Department said Thursday that its producer price index — which measures inflationary pressure before it reaches consumers — rose 2.1% last month from March 2023 , biggest year-over-year jump since April 2023. But economists had forecast a 2.2% increase, according to a survey of forecasters by the data firm FactSet.

Yet while the reported inflation rate was below what was forecast, at 2.1% year on year the increase in factory gate prices is still printing too high for the Federal Reserve to feel comfortable they have enough cover to lower the federal funds rate. Inflation continues to confound what the Fed has says it would like to do regarding interest rates. The Fed’s “Holy Grail” of trimming the federal funds rate is steadily being pushed farther and farther out of reach.

The Fed’s problem is, on the surface, fairly simple and straightforward: Inflation is just not moving quickly towards the all-important 2% year on year threshold.

It is the Fed’s belief that, at 2% inflation year on year, the economy will then be stable enough to support trimming the federal funds rate down towards the “neutral” rate of interest, where interest rates neither stimulate nor suppress the economy.

The neutral rate of interest (also called the long-run equilibrium interest rate, the natural rate and, to insiders, r-star or r*) is the short-term interest rate that would prevail when the economy is at full employment and stable inflation: the rate at which monetary policy is neither contractionary nor expansionary. It is a function of the economy’s underlying characteristics and is not set by the Federal Reserve. It’s usually discussed in real terms, that is, with inflation subtracted out. The neutral rate cannot be observed directly; it can only be estimated.

The ultimate endpoint of the Federal Reserve’s interest rate policies is that market interest rates and the federal funds rate should converge at this ephemeral “neutral” rate of interest. Unfortunately for the Fed (and everyone else), there is no way to objectively measure the neutral rate of interest, and there is more than a little dispute over what that rate actually is.

As early as July of 2022, former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers was highly critical of the Federal Reserve’s estimate of where the neutral rate lay, judging the Fed’s estimate was far too low.

“Jay Powell said things that, to be blunt, were analytically indefensible,” Summers said on Bloomberg Television’s “Wall Street Week” with David Westin. “There is no conceivable way that a 2.5% interest rate, in an economy inflating like this, is anywhere near neutral.”

Summers was referring to Fed Chair Jerome Powell’s assessment on Wednesday that, with the latest interest-rate hike, the central bank had already reached a “neutral” setting -- where it’s neither stoking nor restraining consumer prices. Powell also said that the Fed “broadly feels that we need to get policy to, at least, to a moderately restrictive level,” past neutral.

Perhaps partially in response to critics such as Summers, over time the Fed has slowly raised its guesstimate for the neutral rate of interest.

As the Fed maintained its long-run inflation projection at its 2% target, this implies a slight increase in what policymakers deem to be the neutral real rate of interest, or 'R-star', to 0.6% from 0.5%.

These were small changes, particularly to the longer run projection, but they could be significant.

Collectively, they show the Fed recognizes that policy needs to be tighter for longer in the post-pandemic world to get inflation back down to target and keep it there. Seven Fed officials now see a neutral rate of 2.9% or higher, compared with four in December.

Fundamentally, the longer consumer price inflation remains above 2%, the higher the Fed’s estimate on the neutral rate of interest is going to be.

The longer consumer price inflation remains higher than the Fed’s 2% target, the greater the likelihood that the Fed’s “higher for longer” stance on interest rates shifts into “higher forever.”

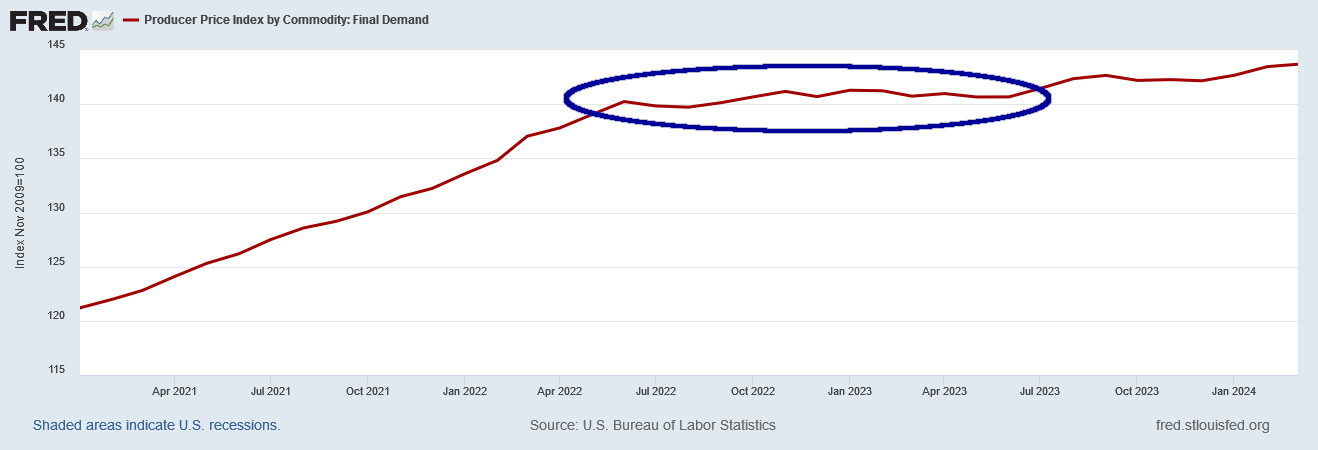

As we can see when we look at the seasonally adjusted PPI chart itself, factory gate prices were largely stable between June of 2022 and June of 2023.

Since then, factory gate prices have shown two small rising trends with a brief interlude of deflation in between.

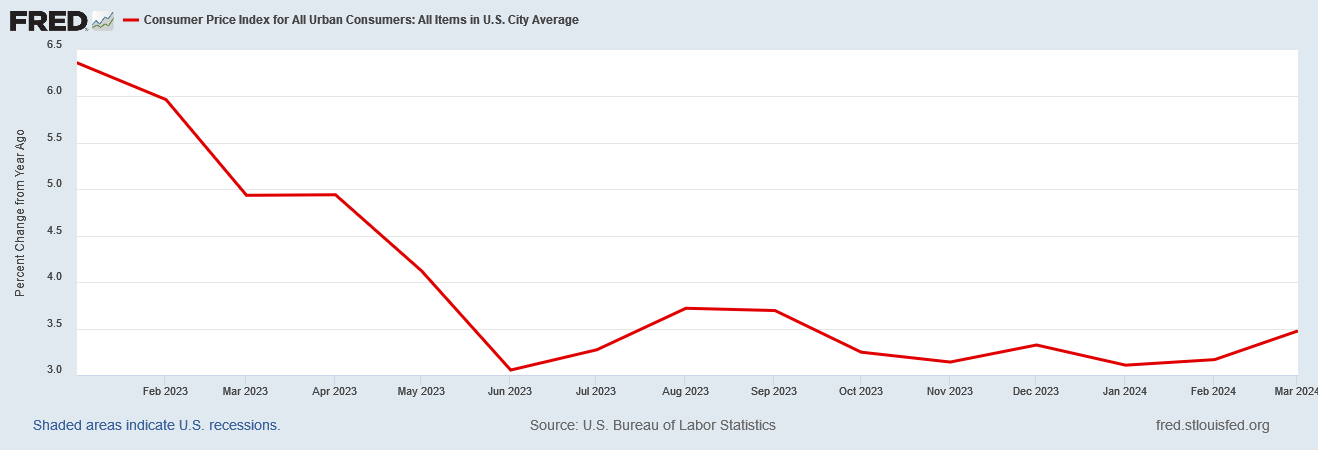

While consumer prices have been consistently rising, we still see indications of the same inflection points as we do for factory gate prices.

These inflection points in the consumer price index chart show when inflation turned to disinflation and vice-versa.

Thus, if factory gate prices are rising in March, we may reasonably expect consumer prices to rise sometime between March and May or perhaps June. With factory gate prices rising, there is little doubt that inflation is not done with us yet. Factory gate prices suggest that consumer price inflation rates are likely to increase over the next couple of months before trending downward once again.

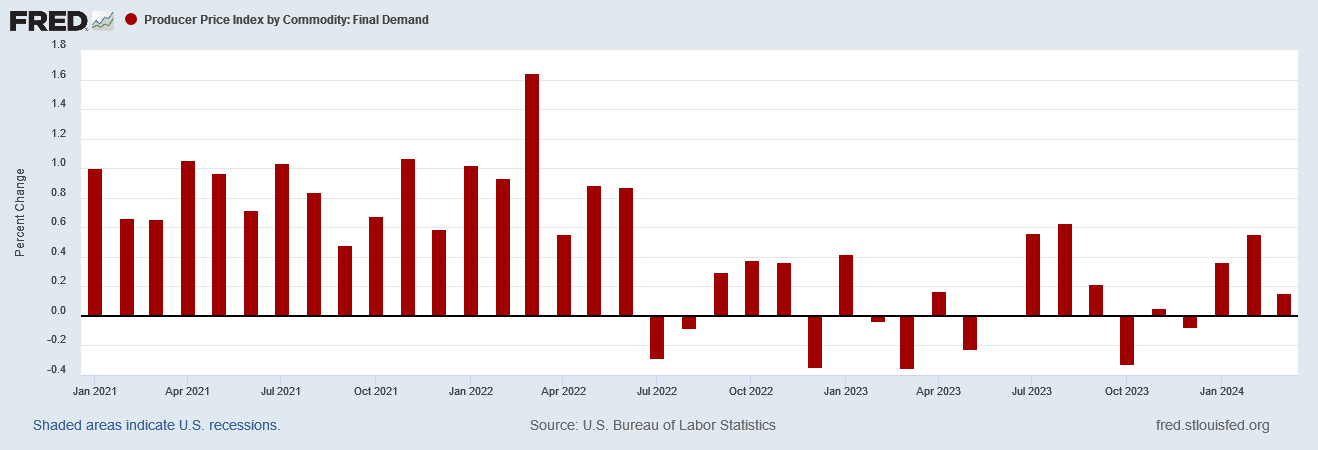

When we look at the month on month inflation rates for factory gate prices, one thing we see quickly is that factory gate inflation all but evaporated in June of 2022.

However, beginning in July of 2023, we again see a period of factory gate inflation, followed by factory gate deflation, followed by factory gate inflation, which at three months’ duration each are more definitive trends than prior months back to June of 2022.

This is a strong signal that factory gate inflation is heating up again—and that means consumer price inflation is going to be heating up even more.

If the rates of inflation are increasing, the Fed would need a compelling economic logic for a stimulative rate cut before it could rationally proceed with trimming rates.

That inflation is threatening to heat up again is presenting Wall Street with a conundrum: what if inflation simply never gets back down to 2%? Could inflation become structural at around 3%?

Yes.

The latest data raises two different possibilities. One is that the Fed’s expectation that inflation continues to move lower but in an uneven and “bumpy” fashion is still intact—but with bigger bumps. In such a scenario, a delayed and slower pace of rate cuts is still possible this year.

A second possibility is that inflation, rather than on a “bumpy” path to 2%, is getting stuck at a level closer to 3%. Without evidence that the economy is slowing more notably, that could scrap the case for cuts altogether.

“Underlying inflation is down. We have made progress. Frankly, we’ve made more progress than I would have expected a year ago,” said Jason Furman, a Harvard University economist. “But we’ve made less progress than anyone was hoping for three months ago.”

Structural consumer price inflation at around 3% is looking quite credible, especially since year on year consumer price inflation per the CPI has broadly bottomed out just above 3%.

Even “core inflation” is showing signs of having bottomed out at ~3.76% over the past two months.

Even the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge, the PCEPI, cannot quite get down to 2%, although it has gotten closer than the CPI has.

These are not absolute proofs of a structurally embedded rate of consumer price inflation, but the data does suggest that there may be a “floor” to inflation rates—and that is not any sort of good news.

If consumer price inflation has become structural, then the Fed will never be able to reduce the federal funds rate without sparking more runaway inflation such as we saw in 2022. The federal funds rate—and even market interest rates—would be effectively fixed at around 5.25-5.5% indefinitely.

Readers may recall that I speculated on this very scenario last fall.

With oil prices having found both a floor and a ceiling price recently, in the aftermath of the OPEC+ production cuts, it is difficult to envision energy price deflation continuing for very much longer. If Saudi Arabia and Russia follow through with their commitment to extend their production cuts past September, it is even possible that energy price inflation could return, amplifying core consumer price inflation and sending both core and headline rates up again.

With energy prices stabilizing and even moving higher, we are very likely seeing a “bottoming out” of the disinflation of the past year. If this proves to be the case, the July increases in headline inflation (and in PCE core inflation) will not be the last.

The inflation data since I wrote that has largely confirmed that speculation—we have seen an effective “bottoming out” of consumer price inflation per the CPI, and with energy prices on the rise in a major way, we are now seeing consumer price inflation starting to heat up again.

The PPI is largely reinforcing this view of the data.

If this trend continues, not only will there not be a rate cut in June as had previously been anticipated, but the Federal Reserve may find itself compelled to actually raise the federal funds rate. That is Larry Summers’ take on the current state of inflation.

Former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers said Wednesday the March CPI report raises the odds that the Fed will hike rates.

“You have to take seriously the possibility that the next rate move will be upwards rather than downwards,” Summers said in a Bloomberg TV interview Wednesday.

Summers was one of a handful of economists who correctly argued back in 2021 that inflation wasn’t transitory, as Fed officials had categorized it, and rather was more widespread and would prove to not be temporary.

If this trend continues, even Wall Street will have to acknowledge that the Fed has no real control over interest rates and monetary policy, and certainly has no control over what happens next to inflation.

If this trend continues, whatever the Fed does next will only make the outlook for the US economy that much worse.

Winning is not an option for the Federal Reserve. Not in this economy.

"Top Economists Including Barack Obama’s Treasury Secretary Discover the Real Inflation Number Under Biden Reached 18% and Is Still Hovering at a 40-Year High"

https://www.thegatewaypundit.com/2024/04/top-economists-including-barack-obamas-treasury-secretary-discover/

Is this realistic.

At some point I would be interested in you considering an in depth look at inflation as a de facto tax to address our national tax. Including how it is largely regressive in nature.