Oil Prices Found Their Floor, And Now Their Ceiling

Will OPEC+ Cut Production Further?

The good news in oil markets for this past Friday was that oil closed up 1%.

The bad news is that throughout the week prior oil prices had been sliding, leaving oil prices down for the week.

Oil prices rose about 1% on Friday on signs of slowing U.S. output, but both crude benchmarks also ended their longest weekly rally of 2023 on mounting concerns about global demand growth.

The week before I noted how oil had finally found a floor price, and speculated that a ceiling might not be far off.

Now we know that the ceiling has for now been reached.

The ceiling effect is not merely because oil prices have trended down for a week. There are also signs that oil buying patterns have been particularly price-sensitive, and where some countries were buying and stockpiling oil, rising oil prices are now leading them to tap their inventories.

As is the habit in more or less free markets, rising prices have made oil less attractive, and are presenting their own downward pressure on demand. This price-driven downward demand pressure joins a raft of other downward pressures, which includes China’s steadily deteriorating economic condition.

OPEC is once again on the backfoot, and will soon have to decide if further production cuts are needed or advisable to protect oil prices.

When Brent Crude closed on August 9 at $87.55/bbl, it had reached its highest closing price all year.

West Texas Intermediate similarly enjoyed closing at its 2023 high. Until last Friday, however, the trend ever since has been down, and further down.

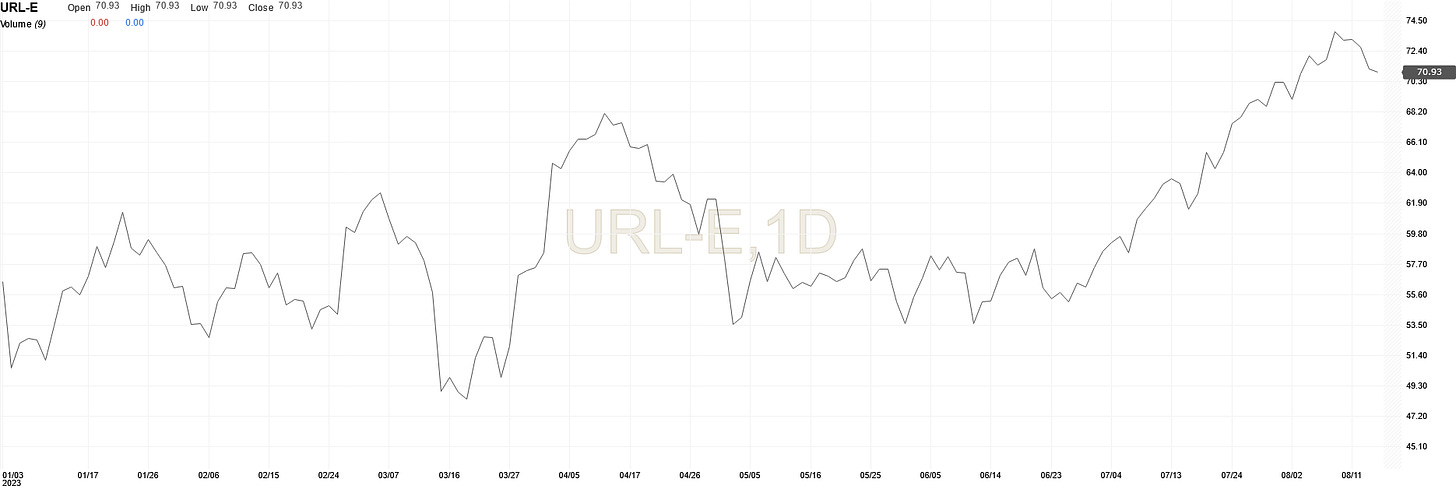

Even Russia’s benchmark Urals crude, which blew apart the EU/NATO price cap weeks ago, is trading well above previous 2023 prices.

At first glance, therefore, one is tempted to conclude that the OPEC and Russia production cuts “worked”.

But did they? Consider how the market has moved.

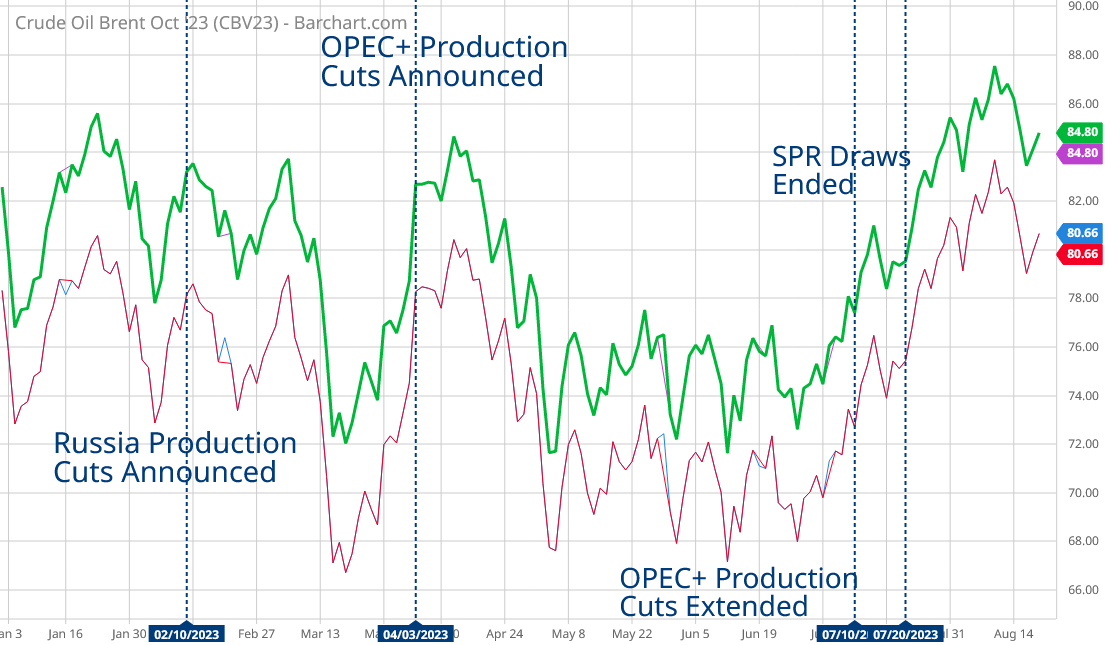

Roughly a month after Russia announced its production cuts, oil prices including Urals crude dropped to a 2023 low.

Barely a week after OPEC announced its production cuts, oil prices peaked, with Brent Crude posting its highest 2023 closing price before August 9 at $84.65/bbl.

Oil prices would remain low for the next two and half months before starting its latest upward trend on June 27. OPEC and Russia extended their production cuts on July 10, and the Biden Regime ended drawdowns from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve on July 20. Roughly three weeks after that, oil hit its new ceiling price of $87.55/bbl and then moved down.

Removing oil capacity from production, thus shrinking oil supply, finally had the effect of not allowing oil prices to drift any lower than they already were, but the extent to which the production cuts have pushed oil prices up is somewhat problematic.

Arguably, Yevgeny Prigozhin’s aborted coup in Russia had more impact in pushing up global oil prices.

Whatever the cause, something besides OPEC and Russian oil production cuts appears to have played a role in boosting oil prices starting.

Similarly, OPEC and Russian oil production cuts have reached the extent of the upward price pressures they have brought to bear. With these dynamics being displayed by market prices for oil, we do well not to overstate the influence the production cuts have had on oil prices. The production cuts have certainly exerted an upward price influence, but last week we saw the extent of their influence.

One fact delimiting the influence the production cuts could have on oil prices has been the extent to which the significant variance between Brent and Urals crude has negatively impacted Saudi (OPEC) oil revenues.

Although Saudi Arabia and Russia are working together to extend production cuts and maintain oil prices, the latter’s extended grasp of the market share given its narrower options is working against the kingdom.

Russia can export to essentially six major consumers, with Turkey, India and China being the major three, said Bey, which impacts Saudi Arabia’s future revenues.

“There is probably some concern from Saudi Arabia’s standpoint that long term, the market share on average that they would normally have might actually start to decline, or at least be peaking,” he added, as Russia becomes more protective of its customers during its restricted state.

On January 3, Urals crude traded at a discount of $23.37/bbl to Brent crude. By April 3, when OPEC announced its production cuts, that discount had slid to $18.04/bbl, with Brent trading at $82.69/bbl. That discount held when Brent crude bottomed out on June 12 at $71.63/bbl. By August 9, when Brent peaked, that discount was down to $13.82/bbl.

Russia has benefited the most from the recent price increases, so much so that Russia increased its export levy on oil. Beginning in September, Russian oil producers will pay into the state coffers roughly $2.92/bbl, an increase of approximately 25%.

The export duty is just one of several levies paid by the country’s oil industry and accounts for a fraction of total petroleum revenue as Russia completes a multi-year tax reform. Moscow is gradually shifting the tax burden to oil production, away from shipments abroad, and plans to abolish the export duty in 2024.

Still, the hike of the duty in the U.S. dollars — combined with a weaker ruble — should help offset Russia’s lower overseas sales of crude in September while boosting budget revenues. The Russian currency has been the third-worst performing among its emerging-market peers this year, falling 25% against the dollar.

While Russia has been successfully siphoning off oil sales from Saudi Arabia, there are indications that the deep discount to Brent crude has been a primary factor in this, and as the discount has eroded, so has the attractiveness of Urals crude.

Last week, after oil prices peaked, Pakistan opted to suspend its imports of Russian oil, citing quality concerns.

The South Asian country blamed the quality of Russian crude for suspending the imports. It noted the refining process of Russian oil yielded more furnace oil than petrol. Refineries in Pakistan have also reportedly refused to process any more Russian crude.

The refineries found that Russian crude oil was producing 20% more furnace oil than Arabian crude. Russian oil also yielded less kerosene and jet fuel for ships and hence was deemed less profitable for Pakistan, reports said.

It was reported earlier this month that Pakistan's ports were finding it harder to handle the large vessels that depart from Russia with crude, while vessels from Middle Eastern countries were easier to handle.

Intriguingly, as Russian oil prices have risen, Greek tanker operators, who are the most significant tanker fleet moving Russian oil, have curtailed their involvement in that trade.

But now Greek-operated tankers are cutting their volumes of Russian crude after the price of Urals surpassed the US$60/bbl price cap for the first time in July. According to Argus Media, Greek tanker operators, who control more than one-third of tankers which have been lifting Russian crude post-ban, cut volumes of Russian crude by 482,000 bbls in July, with current volumes good for 35% of all cargoes compared to 45% in June. With Russian crude now more costly, Chinese buyers are increasingly turning elsewhere which further disincentivizes Greek operators from remaining in the Russian trade due to the complications of remaining sanctions-compliant.

The reaction of Greek tanker operators confirms reports that China is choosing for now to draw down its built-up oil inventories rather than purchase oil.

China, the world's top crude importer, is drawing on record inventories amassed earlier this year as refiners scale back purchases after OPEC+ supply cuts drove global prices above $80 a barrel, traders and analysts said.

Chinese refiners, led by Sinopec and PetroChina, have built a supply buffer using massive storage capacity constructed over the past decade that gave buyers flexibility to boost purchases when prices are low and cut back when oil becomes expensive.

Simply put, China (and very likely India, another major purchaser of Russian oil in particular) was quite willing to purchase significant amounts of oil well above its immediate demand in order to build up a stockpile against the day when prices would rise again. Now that day has arrived, and China is leveraging that stockpile to minimize its exposure to high oil prices.

While the IEA has gushed frequently about “record oil demand”, a significant portion of that presumed demand has been driven by the desire to stockpile oil against future price hikes.

Yet China’s current economic problems, coupled with a weakening global economic outlook, are now starting to weigh on future oil demand, so that even the IEA is trimming its demand forecast for 2024:

With the post-pandemic rebound running out of steam, and as lacklustre economic conditions, tighter efficiency standards and new electric vehicles weigh on use, growth is forecast to slow to 1 mb/d in 2024.

In another exemplar of economic contagion, the contractions within China’s real estate markets is reducing construction efforts, which in turn is reducing projected demand within China for diesel fuel.

Lower forecasts of Chinese diesel consumption further illustrate the struggles of the world's second-largest economy and oil consumer to regain its footing following the pandemic. With equipment idling as construction slows and dwindling exports curb manufacturing, diesel demand is likely to ebb.

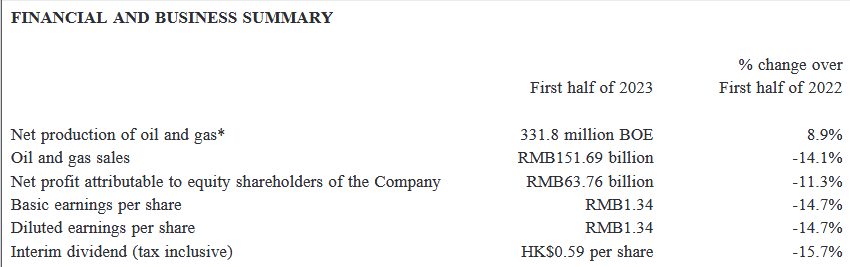

At the same time, China’s own oil producer, CNOOC, has posted double digit profit declines for the first half of 2023 relative to the first half of 2022.

Even though its production of oil and gas was nearly 9% higher than in 2022, net revenues declined. Oil “demand” existed primarily because oil was cheap.

Now that oil is less cheap, demand is proving to be less as well.

While market realities are painting a picture of steady or diminished oil demand going forward, some market analysts, particularly, Goldman Sachs, are clinging to a more optimistic view of oil prices.

Goldman estimates global oil demand rose to an all-time high in July and revised up its 2023 demand forecast to about 500,000 barrels per day.

Goldman Sachs is maintaining its 12-month-ahead forecast of $93 per barrel for Brent crude and $86 in December 2023. Brent crude settled near $85.50 on Monday.

Essentially, the Vampire Squid is choosing to overlook the stockpiling of crude by China, as well as the sales cannabilism between Russia and Saudia Arabia, both of which speak to an environment of decreased, not increased, oil demand.

With the global economic outlook dampening future oil demand, the various pressures described above are far more likely to converge to establish a ceiling on oil prices at around ~$87-$88/bbl. A dramatic change in the global economy and global oil demand will be needed before that ceiling can be breached.

This scenario is reinforced by the reality that global oil production shrank in July by nearly a million barrels per day—and yet prices still peaked August 9. Whatever the extent of upward price pressures on oil by the OPEC+ production cuts has been, that price pressure appears to have reached its maximum influence on August 9.

Which leaves both Russia and Saudia Arabia in a bind. If demand, particularly from China, continues to weaken—a likely scenario, given their recent economic problems—oil prices over the next few weeks and months are almost certain to trend down. $87/bbl might be the ceiling for oil prices, but it is not necessarily where oil prices are going to be most of the time. At the same time, the diminution of the discount on Russian oil is making Russian oil less attractive on the open market, further eroding its revenue position.

OPEC can, of course, issue further production cuts. Yet without an external increase in oil demand, future production cuts are likely to equate with reduced oil revenues all around. The purpose of the production cuts has been to protect oil prices and, by extension oil revenues. Further production cuts might stabilize oil prices, but they would do so at the expense of oil revenues.

It is problematic at the moment whether oil prices will fall much at this juncture. Some further decrease is possible as markets fully digest the recent bits of economic bad news worldwide. Without a significant influx of economic good news, it is difficult to see much upward impetus for oil prices. With the global economy acknowledged to be slowing and weakening, it is far more likely at this point for oil prices to trend down rather than up.

There's a certain satisfaction when the markets decide to agree with me.

https://www.benzinga.com/amp/content/33963274

Regardless of why oil finds its price ceiling, what matters is that it is finding a ceiling. This delimits oil's capacity to influence consumer price inflation as well as various measures of industrial output.