Just a few days ago, I pondered the possibility that China was sliding into a period of deflation, stagnation—in nearly every regard a replay of Japan’s “lost decade”.

On Tuesday and Wednesday, China’s latest data on export and import volumes was released as well as inflation, and gave what is very likely the final answer on the question: Deflation has landed in China, and is steadily creeping throughout the economy.

The Chinese economy is expected to have slipped into deflation amid signs of a faltering post-pandemic recovery, according to market forecasters.

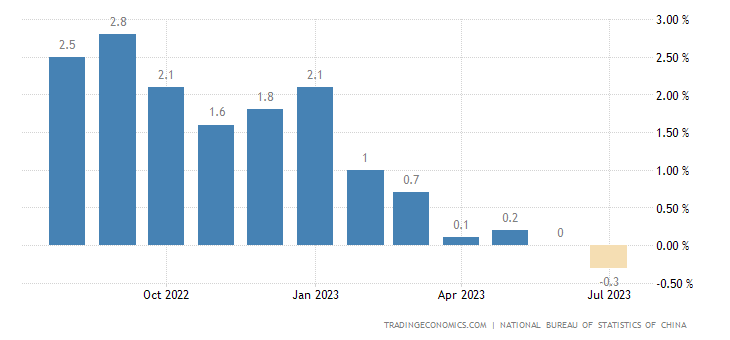

Chinese consumer price inflation data is due to be released on Wednesday, and a Reuters poll of economists suggests it will show that prices fell by 0.4% year-on-year in July, having been flat on an annual basis in June.

That would be China’s first negative inflation reading since early 2021, when prices were weaker as the Covid-19 pandemic hit demand, and pork prices fell.

That Tuesday prediction was nearly spot on, as China’s consumer price inflation data showed that prices did indeed fall 0.3% year on year:

Month on month, China’s consumer prices avoided their sixth consecutive monthly decline, rising 0.2% from June.

Ultimately, this outcome has been inevitable for quite some time. After a brief deflation episode in early 2021, consumer price inflation rose in China, peaking in September 2022 at 2.8%. Inflation has been trending down ever since.

Having reached the zero bound, the next step of going negative—of tipping into outright deflation—was, all things considered, a foregone conclusion.

Additionally, China’s Producer Price Index declined 4.4% in July—worse than the expected 4.1%, and the tenth straight monthly decline.

Producer prices generally presage future movements in consumer prices. China is facing a significant deflationary price pressure because of its persistently declining PPI.

This is no small deflation signal. This is a loud blaring “DEFLATION!” klaxon, and its sounding over the Chinese economy.

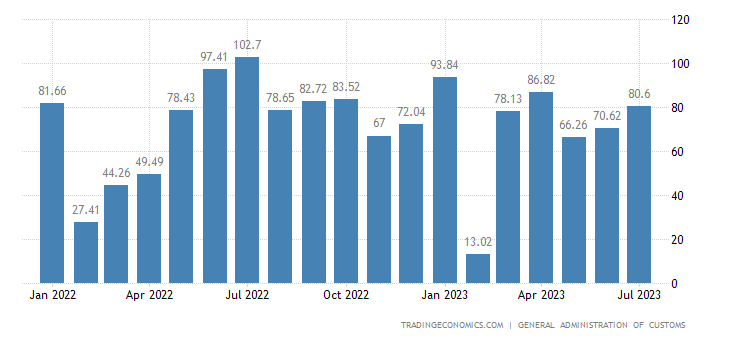

Nor was the CPI data the only bad news China has received. On Tuesday, it published its latest data on exports and imports—and both declined in July by double digits.

China’s exports plunged by 14.5% in July compared with a year earlier, adding to pressure on the ruling Communist Party to reverse an economic slump.

Imports tumbled 12.4%, customs data showed Tuesday, in a blow to global exporters that look to China as one of the biggest markets for industrial materials, food and consumer goods.

The export decline was the third consecutive such decline.

The import decline was the fifth such monthly figure.

In posting these declines, China also saw its trade surplus give up some $22.1 Billion from July, 2022.

Even though the trade surplus has crept up in recent months, the longer macro trend is still down.

Exports down—hard.

Imports down—harder.

Trade surplus down year on year.

Consumer prices down year on year and month on month.

There can be no doubt about this: China has entered a deflationary phase to their economic contraction.

The immediate impact of China’s export and import data on global oil prices was almost immediate, with the weak trade data sending a massive bearish signal through the market, sending prices for both Brent and West Texas Intermediate down upon opening.

While oil prices recovered and even finished Tuesday’s trading eking out a small gain, the decline was still enough to keep Brent Crude from pushing past its most recent peak price until yesterday..

Moreover, Russia’s benchmark Urals crude declined slightly on the China news.

This despite OPEC’s own benchmark, the OPEC Basket blend, inching slightly higher.

There was little doubt that China’s economic news was the catalyst for the decline:

Today's weak Chinese trade news signals weakness in China's economy and is negative for crude demand. China Jul exports fell -14.5% y/y, weaker than expectations of -13.2% y/y and the biggest decline in nearly 3-1/2 years. Also, Jul imports fell -12.4% y/y, weaker than expectations of -5.6% y/y and the biggest decline in 6 months.

Other news of weakness in Chinese crude demand is bearish for prices after government trade data showed China's July crude imports fell -19% m/m to 10.33 million bpd, the smallest volume in 6 months. Also, Vortexa said China's onshore crude inventories have expanded to a record 1.02 billion bbl.

Falling exports and expanding inventories suggest China is not selling either crude oil or refined products at previous sales volumes. Falling imports suggest China is not buying crude oil either—at least not at previous sales volume.

Dampened prospects for China oil demand further reinforces the prospect that benchmark Brent crude and West Texas Intermediate have or will shortly peak, after which price declines could become the prevailing trend.

This, of course, would paint Saudi Arabia and Russia into an awkward corner, where they are compelled to trim production even further just to support current price levels.

The fall in China’s exports also highlights another challenge for Beijing, and for economic policy makers around the world: global demand is simply not there. It certainly is not rising, and it definitely is not rising for Chinese goods.

China’s exports helped prop up its economy during three years of closure to the world but have struggled in 2023 as high global inflation and rising interest rates damped demand for Chinese goods. Exports have declined year on year in each of the past three months, dropping 12.4 per cent in June, when imports also shed 6.8 per cent.

The protracted decline in manufacturing export orders confirms this.

As if to punctuate the global weakness, even China’s ability to export services is shrinking of late.

As the Financial Times notes, this presents its own concerns, as the falling import volumes highlight China’s weak domestic demand and relative inability to growt its economy through domestic consumption.

The fall in imports also highlights how trade concerns are shifting from weaker external demand to the strength of domestic consumption more than half a year after Covid-19 restrictions were lifted.

As a direct consequence of the weakness in both export and domestic demand, China’s quarter on quarter GDP growth has dropped to a barely conscious 0.8% for the second quarter of 2023.

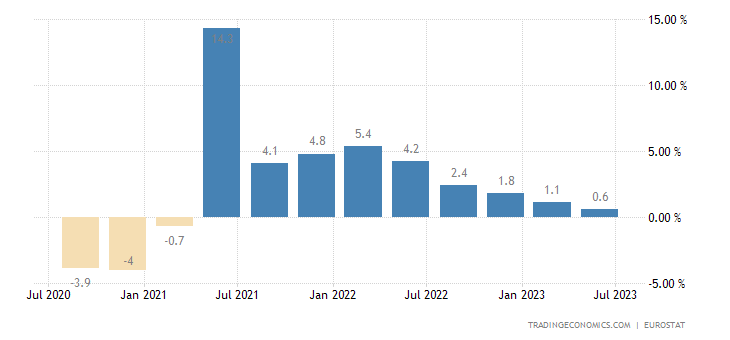

The Euro Area, home to several China trading partners, is showing similar GDP weakness and decline.

If you take these statistics at face value (I do not recommend doing that!), the United States is one of the few areas where GDP growth is trending positive in 2023.

Thus we see the true macro ramifications of China’s Japanification. China’s economic slowdown is both feeding and is fed by a global economic slowdown. China’s economic doldrums will reverberate through to the United States as well as Europe. There is no part of the globe which is poised to benefit from a deflating Chinese economy.

With a global economic slowdown unfolding right before us, the global economy will not be bailing out China’s economy, nor will China’s economy be bailing out the global economy. With softening global demand, China will have to revive its economy entirely on its own.

This will prove challenging, for China’s normal channels for economic stimulus—regional and local governments, as well as their off-the-books Local Government Financing Vehicles (LGFVs)—are already saddled with too much debt. In many cases, the LGFVs are teetering on the brink of insolvency, with several already in arrears on debt service.

China’s local government financing vehicles are showing more signs of stress, with a record number of them missing payments for a popular type of short-term debt last month.

A total of 48 LGFVs were overdue on commercial paper, which typically carries a maturity of less than a year, up from 29 in June, according to a Huaan Securities Co. report citing data from the Shanghai Commercial Paper Exchange. Their missed payments amounted to 1.86 billion yuan ($259 million), versus 780 million yuan in June.

The prevailing wisdom for the deflationary situation China finds itself in is to enact massive monetary and fiscal stimulus to restart the country’s economic engines. China did this back in 2008, during the Great Financial Crisis, and while it did help revive the economy, it also contributed to the unwieldy debt burdens China and China state enties must address now.

China’s economic trajectory is of great concern for global investors and policymakers who are counting on it to drive global expansion. But, Beijing appears to have run out of ammunition.

Back in 2008, Chinese leaders rolled out a four trillion yuan ($586 billion) fiscal package to minimize the impact of the global financial crisis. It was seen as a success and helped boost Beijing’s domestic and international political standing as well as China’s economic growth, which soared to more than 9% in the second half of 2009.

But the measures, which were focused on government-led infrastructure projects, also led to an unprecedented credit expansion and massive increase in local government debt, from which the economy is still struggling to recover. In 2012, Beijing said it wouldn’t be doing it again. The costs were just too high.

Of course, the prescription for massive monetary and fiscal stimulus presumes that such measures would work. We should note that Japan, under the rubric of “Abenomics”, has for the past several years attempted to do exactly what China needs to do now and restart its economy.

Robust economic growth has not happened in Japan. There is little reason to anticipate that it would happen in China.

There is equally little reason to anticipate that a program of massive monetary and fiscal stimulus would return the US to robust economic growth—and while the US economy is largely seen as grappline with high (but receding) inflation, the reality of the stagflation scenario we are seeing in the US is that deflation and inflation can go hand in hand, as both forms of economic disequilibrium exert distorting forces on relative price levels.

Japan’s woes are becoming China’s woes, and to some degree will become—are already becoming—America’s woes. That which did not work for Japan will not work for China nor will it work for the United States.

That’s a rather scary reality, because the “experts” who notionally claim to be able to address such issues even in this country know only this one approach to economic recovery and rehabilitation. As China’s economy sinks deeper and deeper into a deflationary quagmire, the US economy is sinking into a stagflationary quagmire, yet neither Beijing nor Washington DC have displayed any awareness either of the problem or the very real limitations and consequences of the politically preferred “solution”.

How deep will China’s deflation episode be? How long will it last? Will China endure Japan’s multiple “lost decades”?

There is, of course, no way to know the answers to these questions. What we do know is that China’s path into (and eventually out of) deflation will happen not because of what Beijing will do to combat consumer price deflation but in spite of it.

This is great, considering how hard it is to find credible information about china. World just watches China doing its own thing.