Corporate media has a strange notion of “slowing inflation”.

In the July Personal Income and Outlays Report, the PCE Price Index rose at both the headline and core levels, and corporate media defines that as “slowing inflation.”

From the preceding month, the PCE price index for July increased 0.2 percent (table 9). Prices for goods decreased 0.3 percent and prices for services increased 0.4 percent. Food prices increased 0.2 percent and energy prices increased 0.1 percent. Excluding food and energy, the PCE price index increased 0.2 percent. Detailed monthly PCE price indexes can be found on Table 2.4.4U.

From the same month one year ago, the PCE price index for July increased 3.3 percent (table 11). Prices for goods decreased 0.5 percent and prices for services increased 5.2 percent. Food prices increased 3.5 percent and energy prices decreased 14.6 percent. Excluding food and energy, the PCE price index increased 4.2 percent from one year ago.

Yet Reuters framed these inflation numbers this way:

U.S. consumer spending accelerated in July, but slowing inflation strengthened expectations that the Federal Reserve would keep interest rates unchanged next month.

In reality, what appears to be slowing is disinflation. With PCE upticks at both headline and core levels for July, the potential that inflation has “bottomed out” has to be considered. If inflation has bottomed out, the Fed will find itself having to either enact draconian rate hikes or jettison its inflation strategy altogether, as it will have failed to bring the inflation down to the Fed’s Holy Grail of 2% year on year.

Let’s focus first on the part from Reuters about “consumer spending accelerated”.

Specifically, in July personal consumption expenditures rose $144.6 billion, while disposable income barely increased, rising only $7.3 billion.

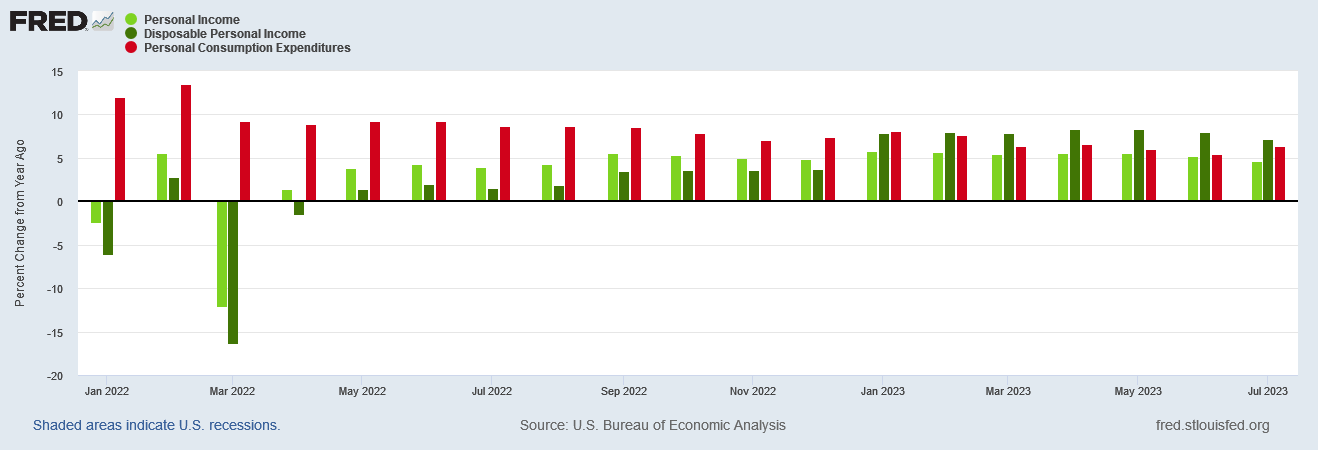

July was the second straight month of accelerating personal consumption expenditures and decelerating personal income and disposable personal income.

Even viewed year on year, July marked a continuation of a trend of slowing growth in nominal personal and disposable personal income, with personal consumption expenditures slowing just a little bit more.

A bit of context: over the longer term, the data is somewhat more encouraging. Disposable personal income in 2023 is generally rose faster than in 2022, and personal consumption expenditures generally rose slower, which makes 2023 a better year than 2022. However, within 2023 that positive trend appears to have peaked and is heading down again.

Another bit of context: the prior month adjustments to the PCE data are significant, with disposable income shrinking by $22 billion in June and expenditures expanding $14 Billion just on revisions alone—meaning June was much worse than first presented.

Small wonder consumer price inflation per the PCEPI ticked up: people succeeded in bidding up prices—i.e., catalyzed the inflation mechanism.

Expenditures accelerating and income decelerating is almost guaranteed to result in inflation—and it has.

July also marks another worrisome trend: the divergence between headline and core inflation for both the PCEPI and the CPI.

Headline inflation for both indices is converging at a lower number, even as both indices are converging at the core level.

With core inflation per the PCEPI not having shifted much in 2023, we are looking at a structurally—and potentially long term—rate of inflation. Should that happen, the Fed will no longer be able even to pretend its rate hike strategy has had much impact on inflation.

Consider the impact of the divergence trend just over the past year: even during a largely disinflationary period, prices per both the PCEPI and the CPI rose roughly 3% since June of 2022 (when inflation peaked), while in both indices less food and energy prices rose approximately 5%.

Another indication of “embedded” inflation not amenable to monetary manipulations: From December, 2022 through May of this year, core inflation per the PCEPI barely changed, and in the core CPI the decrease in inflation slowed dramatically.

In both indices the primary driver of disinflation over the past year has been energy price disinflation and deflation—the energy subindex on both following an almost identical track

The larger the impact of energy price deflation on the overall price indices, the smaller the amount of disinflation in the respective core indices. Energy price deflation has thus masked fairly minimal progress in reducing core inflation, whether one looks at the CPI or the PCEPI.

Given that the Fed focuses more on the core inflation rate, owing to the inherently more volatile nature of energy prices, virtually all of the progress on reducing inflation has come in the one area where such progress is almost guaranteed to be “transitory”. Irony abounds.

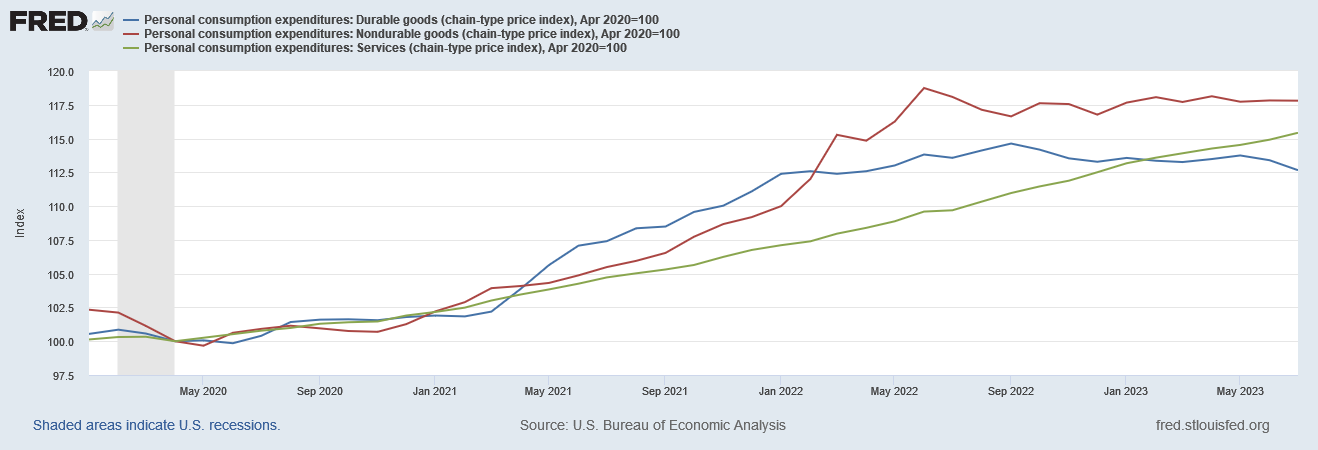

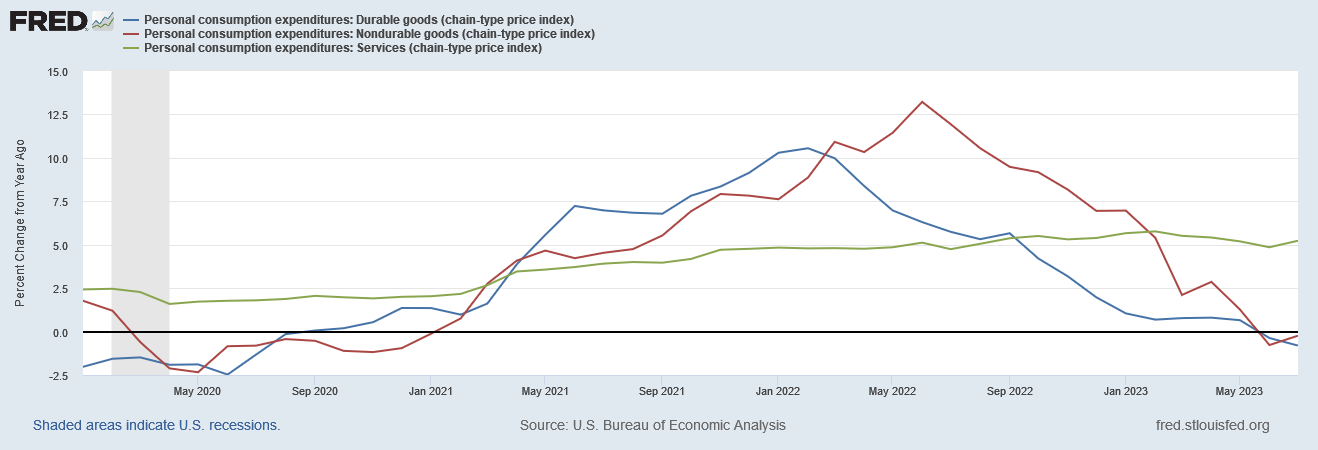

Delving into the PCE Price Index further, we see another dynamic that works to frustrate the Fed’s goal of 2% inflation: Virtually nothing has altered the rate of increase in service prices since the end of the Pandemic Panic Recession, while the prices for both durable and non-durable goods have largely plateaued since June of last year.

As a direct result of this, service price inflation has been rising steadily since the end of the recession, even as goods price inflation has risen, peaked between February and June of last year, and has flipped to outright deflation over the past two months.

The Fed’s interest rate strategy has had zero impact on service price inflation, which is now a dominant factor in consumer price inflation as measured by the PCEPI.

What we are seeing in this is that service prices are driving inflation while goods prices are actually producing mild deflation.

Remember, deflation and inflation concurrently equals stagflation, and that is exactly what the PCEPI has been showing for the past year.

These stagflationary trends in prices have some rather disquieting impacts on overall personal income and outlays as well. Because service price inflation has continued unchecked since 2020, personal outlays have grown considerably faster than both personal incomes and personal disposable incomes.

Since the official end of the Pandemic Panic Recession, personal disposable income has risen just over 5%, personal income has risen 8.6%, while personal outlays have risen 53%.

Unsurprisingly, as a result of these growth dynamics, personal savings since the end of the recession has cratered, and practically disappeared.

This has been the real impact of inflation since the Pandemic Panic Recession: people’s savings are being steadily eroded and erased—and that will set the stage for a new economic crisis of some kind. The best way to catalyze an economic shock is to remove the buffers, and personal savings is a vital buffer against economic shocks on Main Street.

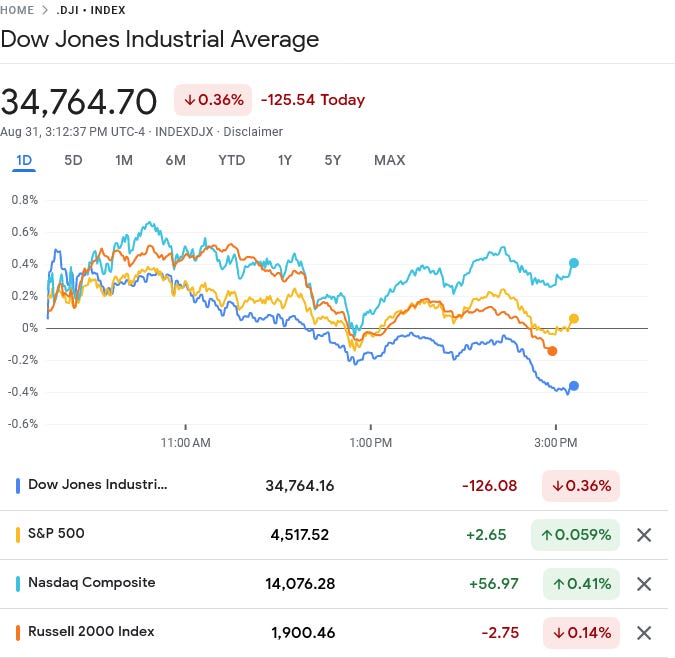

Ironically, Wall Street seems not to be focused on the relative lack of progress on core inflation, as it currently is anticipating the Fed will not raise the federal funds rate at the next FOMC meeting in September, pricing an 88% probability the Fed will hold the line on rates.

This could be a case of the Fed ending hoisted by its own petard, as the corporate media has gone all in on the narrative of the Fed’s rate hike strategy having been a success, and Wall Street has followed along.

Consequently, Wall Street’s reactions to the PCE release by the BEA has been fairly mixed, with the Dow Jones trending down on the day, while the S&P 500 and the NASDAQ have remained in positive territory.

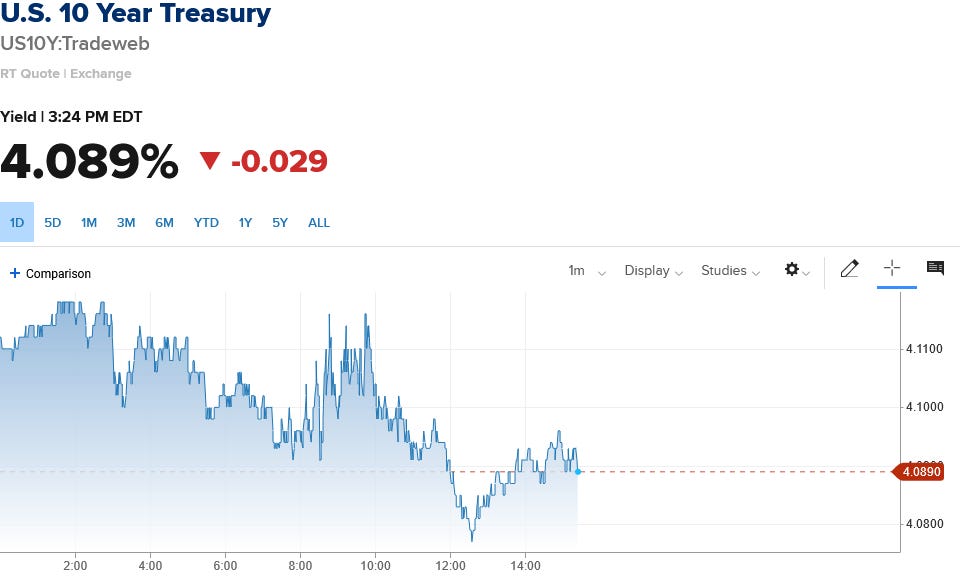

Meanwhile Treasury yields have largely declined on the day, with the 1-Year, 2-Year, and 10-Year Treasuries all trending lower.

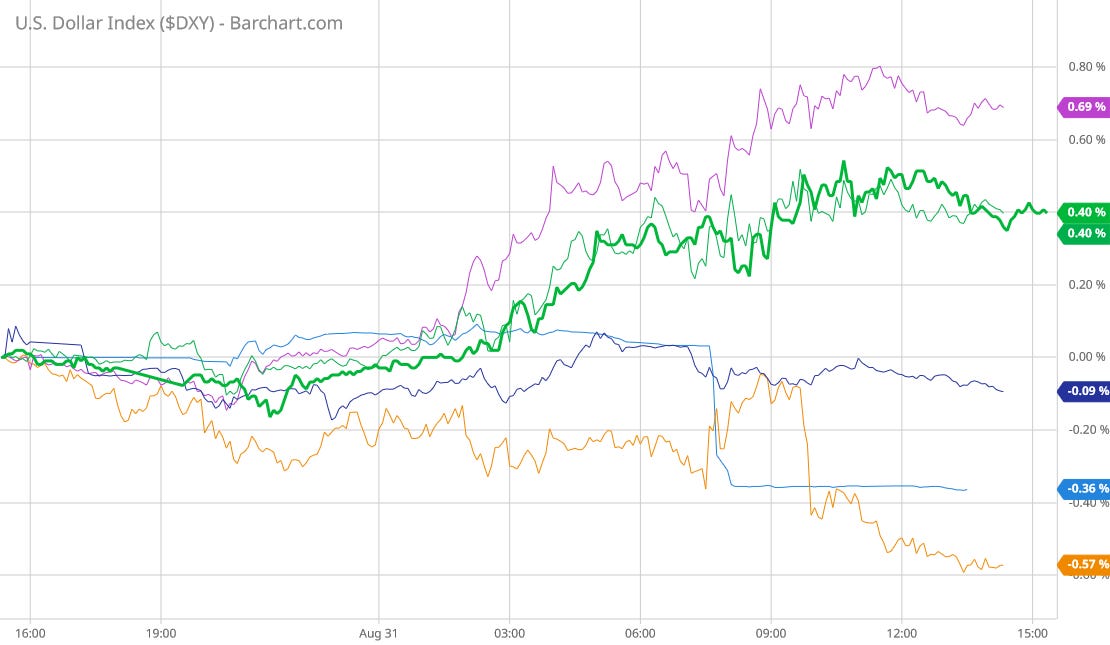

For its part, the dollar has trended mostly higher, posting incremental gains on the euro and the pound sterling, while trending slightly down against the yuan, the yen, and the rupee.

Either the markets fail to realize that the PCE Price Index is signalling higher (and potentially structurally higher) inflation going forward, or they are at peace with consumer price inflation in the 3%-4% range.

While the typical response of the Fed to inflation upticks has been to ramp up the rhetoric and build up expectation of a future rate hike, thus far that expectation has not materialized. Whether that will shift as the date of the next FOMC meeting approaches remains to be seen, but, for now, Wall Street’s reaction to this latest confirmation of ongoing inflation appears to be relatively passive.

This is surprising, because Jay Powell had already doubled down on the 2% inflation objective in his Jackson Hole speech last week.

With the trends visible in the PCE Price Index, not only is 2% inflation not going to happen any time soon, it will be something of a minor miracle of 3% is achieved over the next couple of months, and possibly through the end of the year.

With oil prices having found both a floor and a ceiling price recently, in the aftermath of the OPEC+ production cuts, it is difficult to envision energy price deflation continuing for very much longer. If Saudi Arabia and Russia follow through with their commitment to extend their production cuts past September, it is even possible that energy price inflation could return, amplifying core consumer price inflation and sending both core and headline rates up again.

With energy prices stabilizing and even moving higher, we are very likely seeing a “bottoming out” of the disinflation of the past year. If this proves to be the case, the July increases in headline inflation (and in PCE core inflation) will not be the last.

If inflation does continue to rise, the Fed may very well find itself boxed into a September federal funds rate hike no matter what the prevailing sentiment on the FOMC might be. Perversely, another rate hike will likely not make any difference regarding inflation—the primary drivers of core inflation now have been immune to rate hikes thus far, and there is no reason to believe that has changed.

For all the Fed’s jawboning and rate hikes, inflation is staging a comeback, and it is not done yet. Jay Powell can talk about 2% inflation all he wants, but based on the July PCE report, 2% inflation is not going to happen any time soon.