Jay Powell At Jackson Hole: The Fed May Or May Not Raise Rates, Or Maybe They Won't

Powell Had A Lot Of Words, But Not A Lot To Say

Does Jay Powell understand the economic forces he pretends to manage?

No. If there was any lingering doubt about his competence he removed that with his rambling mostly content-free speech the Fed’s annual Jackson Hole Symposium last week1.

Powell began by taking undeserved credit for bringing inflation down from a high of 9.1% down to July’s 3.3%.

The ongoing episode of high inflation initially emerged from a collision between very strong demand and pandemic-constrained supply. By the time the Federal Open Market Committee raised the policy rate in March 2022, it was clear that bringing down inflation would depend on both the unwinding of the unprecedented pandemic-related demand and supply distortions and on our tightening of monetary policy, which would slow the growth of aggregate demand, allowing supply time to catch up. While these two forces are now working together to bring down inflation, the process still has a long way to go, even with the more favorable recent readings.

Of course, July was also the month that inflation moved up again after declining for months. Powell missed that bit of nuance (along with many others) completely.

Nevertheless, Powell pledged to continue his impotent strategy on inflation until the year on year rate magically wandered down to inflation’s holy grail, 2%.

Turning to the outlook, although further unwinding of pandemic-related distortions should continue to put some downward pressure on inflation, restrictive monetary policy will likely play an increasingly important role. Getting inflation sustainably back down to 2 percent is expected to require a period of below-trend economic growth as well as some softening in labor market conditions.

Left unclear was whether the Fed would or would not be raising the federal funds rate again going forward.

Much of what Powell said was focused on the trends within the Core Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index (Core PCEPI).

On a 12-month basis, core PCE inflation peaked at 5.4 percent in February 2022 and declined gradually to 4.3 percent in July (figure 1, panel B). The lower monthly readings for core inflation in June and July were welcome, but two months of good data are only the beginning of what it will take to build confidence that inflation is moving down sustainably toward our goal. We can't yet know the extent to which these lower readings will continue or where underlying inflation will settle over coming quarters. Twelve-month core inflation is still elevated, and there is substantial further ground to cover to get back to price stability.

As far as this goes, Powell is correct. Core inflation as measured by the PCEPI less food and energy is trending down at the moment.

Within Powell’s view of things, that factory gate prices are showing a trend towards deflation in the future most likely would be taken to mean that inflation will keep coming down.

However, this view is challenged at least partially by the reality that oil prices have recently stabilized at a higher trading band than they have had previously this year.

While the OPEC+ production cuts appear to have stabilized oil at a higher price for now, there is at the moment little price pressure in either direction. Prices are not likely to rise much, but are set to remain high at least for now.

Coupled with a trend towards stagflation throughout the global economy, this suggests that inflation, while it has come down and may come down a little more, is not likely to drift down much more than it already has. Output may decline (and likely will in a variety of industries) but prices are not going to trend down with them.

Powell does not seem to see any of these evidences of future stagflation lurking just around the next corner, and thus he seems to be fairly optimistic about future inflation trends.

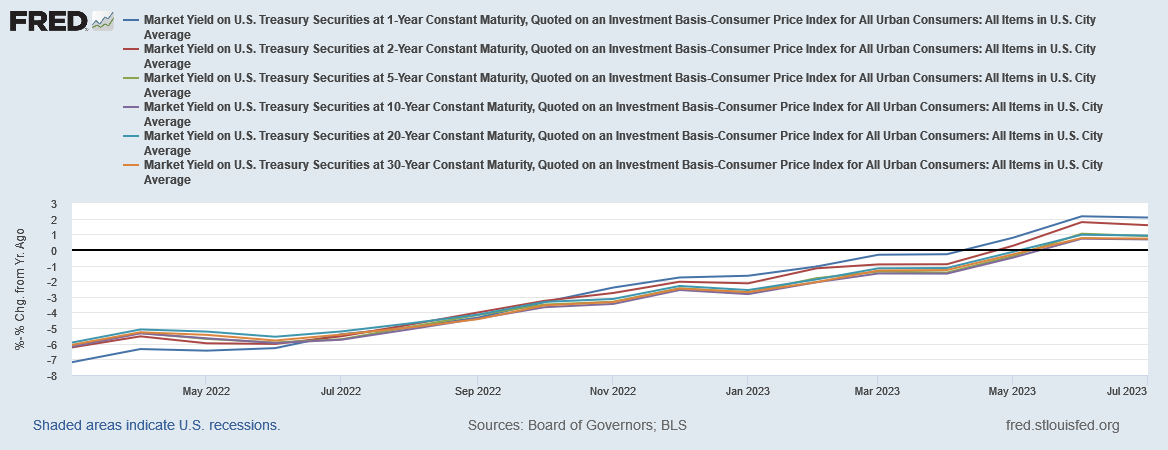

Restrictive monetary policy has tightened financial conditions, supporting the expectation of below-trend growth.5 Since last year's symposium, the two-year real yield is up about 250 basis points, and longer-term real yields are higher as well—by nearly 150 basis points.6 Beyond changes in interest rates, bank lending standards have tightened, and loan growth has slowed sharply.7 Such a tightening of broad financial conditions typically contributes to a slowing in the growth of economic activity, and there is evidence of that in this cycle as well. For example, growth in industrial production has slowed, and the amount spent on residential investment has declined in each of the past five quarters (figure 4).

But we are attentive to signs that the economy may not be cooling as expected. So far this year, GDP (gross domestic product) growth has come in above expectations and above its longer-run trend, and recent readings on consumer spending have been especially robust. In addition, after decelerating sharply over the past 18 months, the housing sector is showing signs of picking back up. Additional evidence of persistently above-trend growth could put further progress on inflation at risk and could warrant further tightening of monetary policy.

Powell appears to believe the Fed will successfully achieve a “soft landing” for the US economy, but he is not grasping that while economic output may be coming down, prices are not always following suit. In particular, PCE measured consumer price inflation for services has only trended down marginally since the beginning of the year, even as consumer price inflation for goods has slipped into outright delation.

Thus while we see growth in industrial production trending down along with a decline in capacity utilization…

This is a straight up stagflationary mix, where we see continued high prices in some areas and falling prices in others, even as overall economic output recedes.

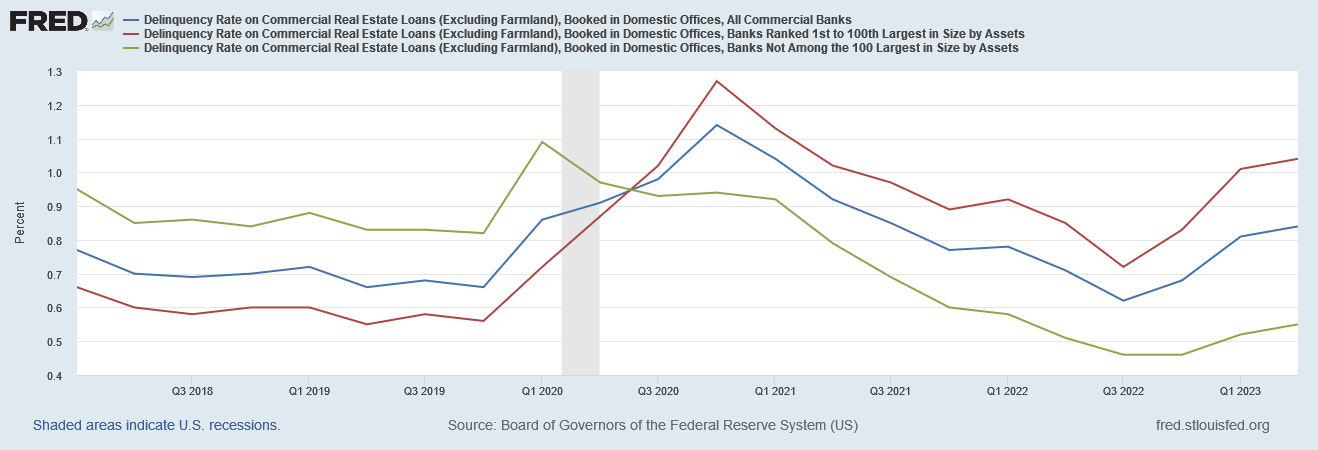

Powell also failed to comment on the potential debt and liquidity crisis lurking around commercial real state in this country. However, despite his silence on the topic, defaults on commercial real estate loans rose again in the second quarter of this year.

This trend is especially worrisome as it is concentrated among the larger banks in the US.

As if to confirm that there is a crisis brewing in commercial real estate, exchange traded funds focusing on mortgage backed securities have lost some 20% of their value just since the start of 2023.

At the same time, bank deposits are down year to date across the whole of the US banking sector.

While bank deposits have largely stabilized recently, what they have not done is recover to their prior levels. The banking situation may not be getting worse, but neither is it getting better.

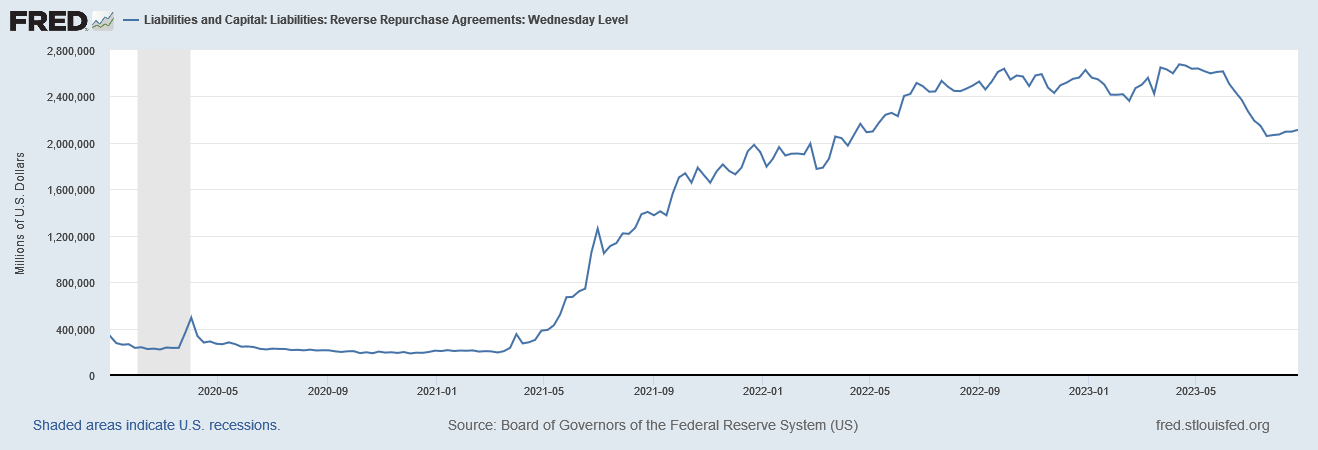

Additionally, with much of that bank money moving into the Fed’s reverse repo market while chasing yield, the ingredients for a fresh liquidity crisis are all there.

If a liquidity crisis does erupt, Powell will quickly find himself in a political position where he will be forced into trimming rates regardless of where inflation is at—and that will likely push inflation back up again. Powell’s Jackson Hole speech makes no mention of these potential crises nor of the likely fallout should they arise.

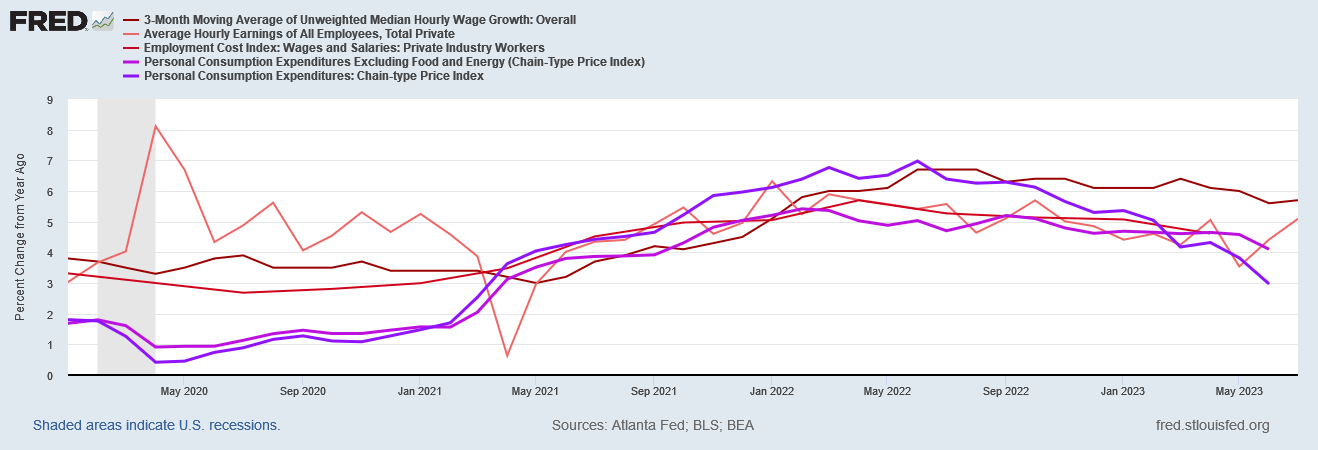

Of course, for Powell, one bright spot was that workers are getting less now.

This rebalancing has eased wage pressures. Wage growth across a range of measures continues to slow, albeit gradually (figure 6). While nominal wage growth must ultimately slow to a rate that is consistent with 2 percent inflation, what matters for households is real wage growth. Even as nominal wage growth has slowed, real wage growth has been increasing as inflation has fallen.

This growth in real wages, of course, is only there if you measure inflation by the PCEPI.

If you compare wage metrics against the CPI, however, real earnings growth disappears completely for all earnings metrics except three month moving average tracked by the Atlanta Federal Reserve.

Having deluded himself into thinking that real wages are rising then they are not, Powell promptly concludes that the trends in wages is a positive—workers get less money so inflation will have to come down, apparently. As per usual for the Fed, when workers get less, that’s a plus for the economy.

Having stumbled and bumbled through his misunderstanding of the economic realities of the United States, Powell could not say definitively whether the Fed would be pursuing a higher federal funds rate or not.

Two percent is and will remain our inflation target. We are committed to achieving and sustaining a stance of monetary policy that is sufficiently restrictive to bring inflation down to that level over time. It is challenging, of course, to know in real time when such a stance has been achieved. There are some challenges that are common to all tightening cycles. For example, real interest rates are now positive and well above mainstream estimates of the neutral policy rate. We see the current stance of policy as restrictive, putting downward pressure on economic activity, hiring, and inflation. But we cannot identify with certainty the neutral rate of interest, and thus there is always uncertainty about the precise level of monetary policy restraint.

All Powell knows is that real interest rates are now positive. Which they are.

What Powell does not know is if rates are high “enough”. Powell also does not know to what extent demand pressures are involved in inflation, versus supply-side constraints which are immune to rate hikes.

Beyond these traditional sources of policy uncertainty, the supply and demand dislocations unique to this cycle raise further complications through their effects on inflation and labor market dynamics. For example, so far, job openings have declined substantially without increasing unemployment—a highly welcome but historically unusual result that appears to reflect large excess demand for labor. In addition, there is evidence that inflation has become more responsive to labor market tightness than was the case in recent decades.8 These changing dynamics may or may not persist, and this uncertainty underscores the need for agile policymaking.

Thus Powell does not know if interest rate are too high, too low, or just right. When you parse the word salad, he all but says as much outright.

Perversely, Powell managed to find the perfect closing metaphor for his cluelessness:

As is often the case, we are navigating by the stars under cloudy skies. In such circumstances, risk-management considerations are critical. At upcoming meetings, we will assess our progress based on the totality of the data and the evolving outlook and risks. Based on this assessment, we will proceed carefully as we decide whether to tighten further or, instead, to hold the policy rate constant and await further data. Restoring price stability is essential to achieving both sides of our dual mandate. We will need price stability to achieve a sustained period of strong labor market conditions that benefit all.

Think that metaphor through: Powell cannot tell where he is, nor can he tell in what direction he should be moving—and yet he is proposing to steer the US economy through its inflationary shoals. This is supposed to give us confidence in his talent for economic navigation.

In truth, no one should have confidence in Jay Powell’s policy guidance. Even Powell himself does not know where he is going to guide monetary policy next, nor does he know what the next monetary crisis will be. He does not know if he will have to confront resurgent inflation, broad-based deflation, or banks running out of cash. He does not know if Wall Street will pressure him to cut rates sooner rather than later (Vegas odds say it will be sooner). Powell simply does not know.

Which is the overall takeaway from Powell’s Jackson Hole speech: He does not know what’s happening.

Despite all the words he used, that’s all he really said.

Powell, J. H. Inflation: Progress and the Path Ahead. 25 Aug. 2023, https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/powell20230825a.htm.

This idiot, Powell, really does not have a clue. Except that it's bad, very bad, when a nation gives away money they haven't even printed yet, but he won't say that, he won't ever say that.

Hard to respect such “leadership”! Ahhhhhh