Inflation Rises, Inflation Falls, Stagflation Stays

Has Inflation Become Embedded In Global Economy?

When the July Consumer Price Index Summary came out, the “experts” all agreed consumer price inflation was under control—even though it wasn’t.

Contrary to the Federal Reserve, the Biden Regime, and the corporate media, inflation is far from being under control. It is for now lower than it has been, but that is all that may be said about consumer price inflation in the US. It certainly cannot be said with confidence that consumer price inflation will be lower tomorrow than it is today—we may find the exact opposite to be the case.

However, while the official narrative on inflation in the United States is one of a successful Federal Reserve campaign against high consumer price inflation, elsewhere inflation has been the problem that has never truly gone away.

Economists are raising their price gains forecast in India for the year after retail inflation last month hit a 15-month high and exceeded market expectations due to a surge in food prices.

Similarly, Norway’s central bank raised its key interest rates 25bps to 4%, in an effort to mimic the Federal Reserve on fighting inflation through higher interest rates.

Norway's central bank raised its benchmark interest rate by 25 basis points (bps) to 4% today to curb inflation, as widely expected, and said it would likely hike again in September.

Today's hike had been expected by all 31 economists polled by Reuters, and a majority of poll participants predicted the rate would hit a peak of 4.25% by the end of the third quarter, in line with the central bank's projection.

And yet we are also presented with unmistakable signs of not just disinflation but potential deflation within the United States.

Meanwhile deflation is becoming the norm for China.

As I have commented before, when deflationary and inflationary pressures coexist within an economy, including the global economy, the result is a fair depiction of what has come to be called “stagflation”—where economic decline and stagnation occurs even as consumer prices remain elevated.

If stagflation is becoming the economic norm across the globe, are we looking at a period of structurally high consumer price inflation? Is some level of consumer price inflation becoming “baked in”, rendering it impervious to central bank manipulations?

There are signs that this is indeed the case.

This stagflationary thesis comes to us courtesy of Jean Boivin and Alex Brazier of the BlackRock Investment Institute.

“Our base case is that the economy broadly flatlines for another year as the full impact of high interest rates comes through and consumers exhaust their pandemic savings,” Jean Boivin, head of the BlackRock Investment Institute, and his deputy head, Alex Brazier, wrote in an Aug. 14 blog post.

A stagnant economy is slightly better than a shrinking one, but Boivin and Brazier noted that if their prediction is correct, the economy will have essentially “flatlined” for two and a half straight years. “That would be the weakest such period in the postwar era outside the Global Financial Crisis,” they explained, referring to the financial meltdown caused by the subprime mortgage crisis in 2008.

There is a particular irony in my citing Wall Street “experts” and speaking of their thesis favorably. However, when there is independent data which comports with that thesis, it does not matter who says it or where they reside. If the logic is sound and the data reliable that is all that matters.

Their thoughts on this topic deserve serious scrutiny. The data supports them.

The core of their stagflation prediction is their view of the declining labor force participation in this country—they view the labor force participation decline as largely a matter of the US population aging.

The population has been ageing. As the Growing older chart below shows, the adult population is steadily rising, but an increasing share of it is now over 64: the point at which many people typically leave the labor force by retiring.[i]

That means a bigger share of the adult population is not in the labor force – which explains the downward trend in the overall participation rate since 2010. It also accounts for most of the 1.1 percentage point drop in the participation rate since the pandemic started: we estimate almost 70% of it. See the green line on the Almost all down to ageing chart below.

Looking at a breakdown of the labor force participation metrics, there does appear to be some substance to this.

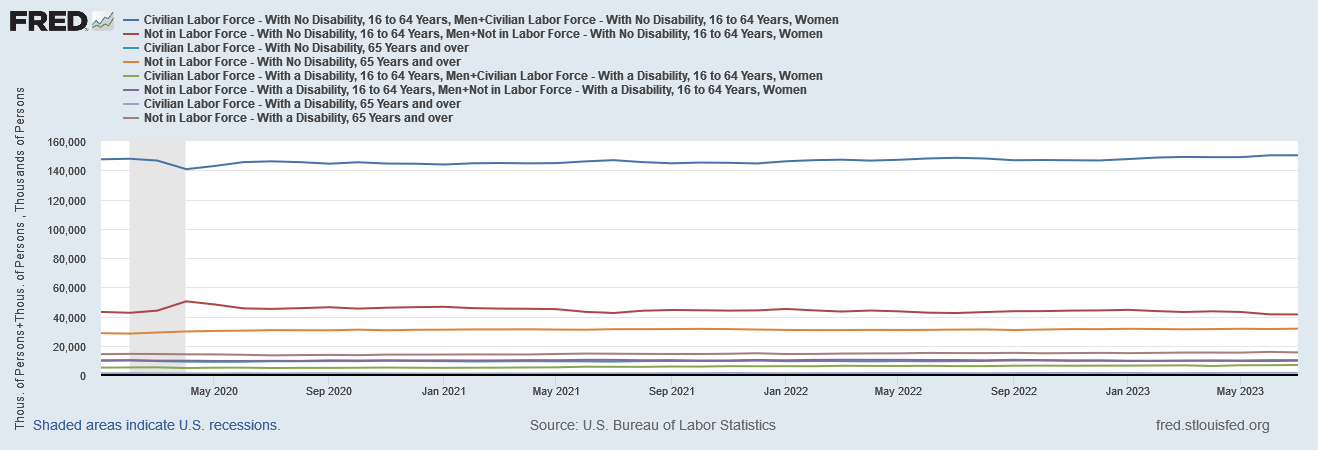

Even looking at the basic numbers themselves, on an unadjusted basis the greatest decline in civilian labor force during the Pandemic Panic Recession was among men and women with no disability between the ages of 16 and 64. The greatest increase during the recession was those not in the labor force for that same demographic.

If we index the demographic cohorts to the start of the Pandemic Panic Recession, we see that men and women, 16 to 64, with no disability rose 1.6% as a part of the labor force by July, 2023, while the portion of that same demographic not in the labor force declined by 2.6%.

However, that part of the labor force 65 and over with no disability declined 1.8% by July, 2023.

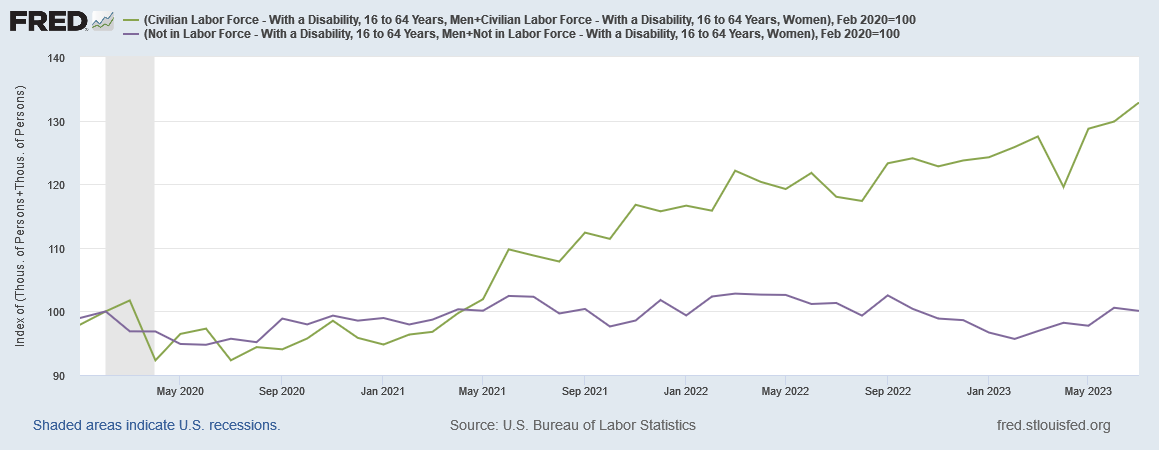

If we focus on the 16 to 64 with no disability cohort, we see that the growth among those not in the labor force exceeded the growth of that cohort in the labor force virtually without interruption until about May of this year.

More people ended up on the sidelines than ended up working. This is a pattern that is antithetical to economic growth and prosperity. This is the pattern that has prevailed for most of the time since the Pandemic Panic Recession notionally “ended”.

Intriguingly, among workers with disabilities, those with disabilities in the labor force grew much faster than those not in the labor force since the start of the Pandemic Panic Recession.

In fact, by far the biggest relative increase among these demographic cohorts was men and women, 16 to 64, with a disability, who were part of the labor force. That cohort increased by 32.8% since the start of the Pandemic Panic Recession.

People over 65 with a disability saw the second largest relative increase at 17.1%

Readers may remember earlier this year I discussed an apparent correlation between mRNA inoculation adverse events and the increase in disabilities within the workforce.

From that correlation we can also, based on these trends, begin to extrapolate some of the broader societal costs of the mRNA inoculations. An inoculation which results in greater levels of disability in and out of the labor force is one that is toxic not just to the person, but to the whole of the economy. If subsequent research should prove out the correlations previously established, the mRNA inoculations will be well and truly damned.

Regardless of the actual cause of the increase in disabled workers, the increase itself impacts worker productivity and overall output (the presumption being, of course, that the presence of a disability negatively affects worker productivity). That we have such an increase suggests an added constraint on economic growth.

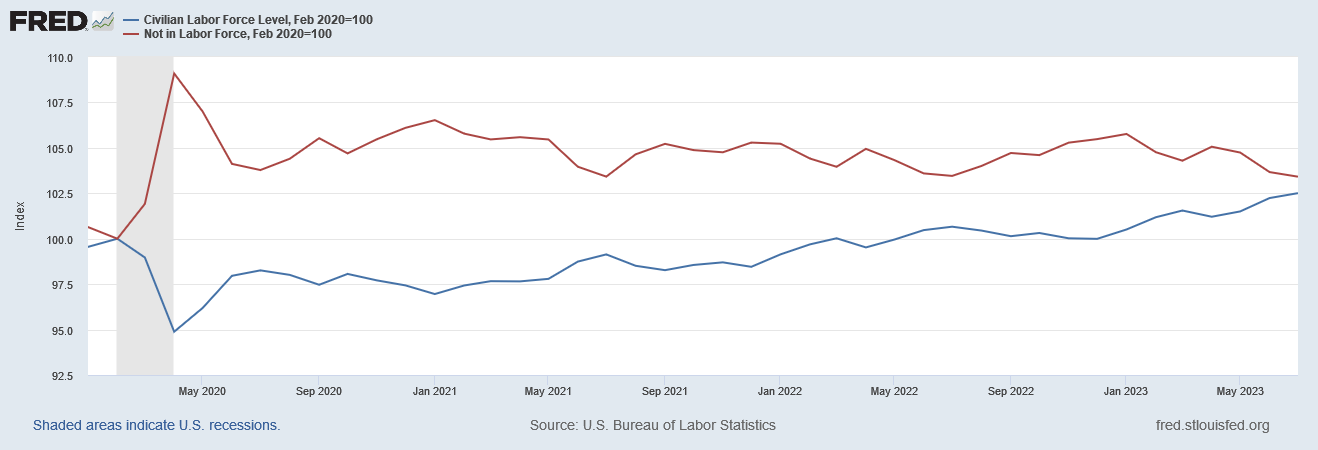

In the aggregate, when we look at the broad unadjusted labor force participation numbers, we see that the labor force in the US has grown since the start of the Pandemic Panic Recession by 2.5%, but that cohort of the civilian population not in the labor force has grown by 3.4%.

The seasonally adjusted labor force data shows an even greater disparity, with the labor force growing by 1.6% but those not in the labor force growing by 5%.

The United States may not be facing the same demographic collapse that China is, but constraints upon the growth of the labor force invariably are constraints on the growth of the economy. Right now, the US economy is clearly constrained. So long as there are impediments to pulling those not in the labor force back into the labor force, the US economy will remain constrained, with reduced potential for increased output and economic growth.

We see some confirmation of this economic constraint in the weekly unemployment data. Readers will recall that the Federal Reserve has stated multiple times that an objective of its federal funds rate hikes has been to increase unemployment in this country.

Yet when we look at the unemployment data side by side with those interest rate rises, we do not see any impact whatsoever of interest rates on employment.

Whatever else is shapes employment in this country at the moment, the Federal Reserve’s rate hikes are not one of those forces.

Yet if the unemployment metrics are impervious to interest rate hikes, we must also consider to what else they might be impervious. Once again we are confronted by the inability of the US economy—of “Bidenomics”—to pull workers off the sidelines and back into the labor force. Once again we are confronted by the reality that the population cohort not in the labor force is growing faster than the population cohort in the labor force.

If workers are not being pulled back into the labor force, regardless of age or disability, then unemployment rates are going to remain low—but that low unemployment rate becomes for that reason a constraint upon employment. Most new entrants to the workforce are going to be counted as unemployed first, until they land a job. With fewer new entrants to the workforce there are fewer new entrants to the ranks of the unemployed.

Consequently, if workers are not pulled off the sidelines the labor force is prevented from growing—and so is the economy.

With an effective although presumably artificial constraint upon the labor force, we begin to see the outlines of how we get deflationary and inflationary pressures coexisting within the economy: as the labor force is a constraint upon economic growth, it pushes the economy towards stagnation.

Yet that same constraint does not operate equally upon consumption. Even people not in the labor force will still consume to some degree, and the growth of that population cohort thus becomes an inflationary pressure within the economy. Regardless of income or wealth levels, any increase in any aggregate population by definition is an increase in aggregate demand.

There are indications that similar confluences of deflationary and inflationary pressures are occurring in other parts of the world as well. While Norway is grappling with inflation still being too high, throughout much of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development consumer price inflation is on the decline. There are distinct trends of disinflation year on year throughout the OECD.

Viewed month on month, we see a similar easing trend on inflation as we move through 2023.

Yet even though inflation is trending down in most parts of Europe, it remains stubbornly high throughout Europe.

Even with deflationary pressures in the US, we also see that core inflation has been particularly intractable, and is still considerably higher than headline inflation.

With inflation remaining high even with the onset of identifiable deflationary pressures in the global economy, we also see more confirmation of what I have pointed out before: central bank rate hikes have been ineffective at confronting consumer price inflation, not just in the US, but everywhere.

If there is a single coordinated theme throughout the world’s economies, it clearly must be “stagflation”. Whether in China, or Japan, or Europe, or the US, economies broadly are in decline.

Yet time after time, particularly outside of China, prices are not in decline. Even as economic output is being constrained, some prices are not adapting to match. Consumer prices are going up….and staying up, even as economic output declines. Deflationary pressures are not eliminating inflationary pressures, nor vice versa.

We can see some of the reasons why this happens in labor force demographics. We have at once scarcity of unemployed people and a surplus of people not in the labor force. There are of course other factors at play (to analyze them all would require a book, not an article!), but the overarching trend is that the world’s economies are operating under various constraints pulling in divergent directions—some push prices up, others push output down.

This is the crux of what stagflation is: divergent forces acting on the economy simultaneously. Think of it as deflation and inflation happening together.

This is what not just the US economy but the global economy is experiencing—sustained, and likely to be prolonged, stagflation.