Has Winter Arrived For Inflation?

We Have Price Stability. Now We Need Wage And Income Growth

In a continuation of the theme for December’s CPI data, winter is either still coming for consumer price inflation, or winter is arriving.

That is the top level takeaway from the Bureau of Economic Analysis’ October and November Personal Income and Outlays report, which saw little overall change in consumer price inflation.

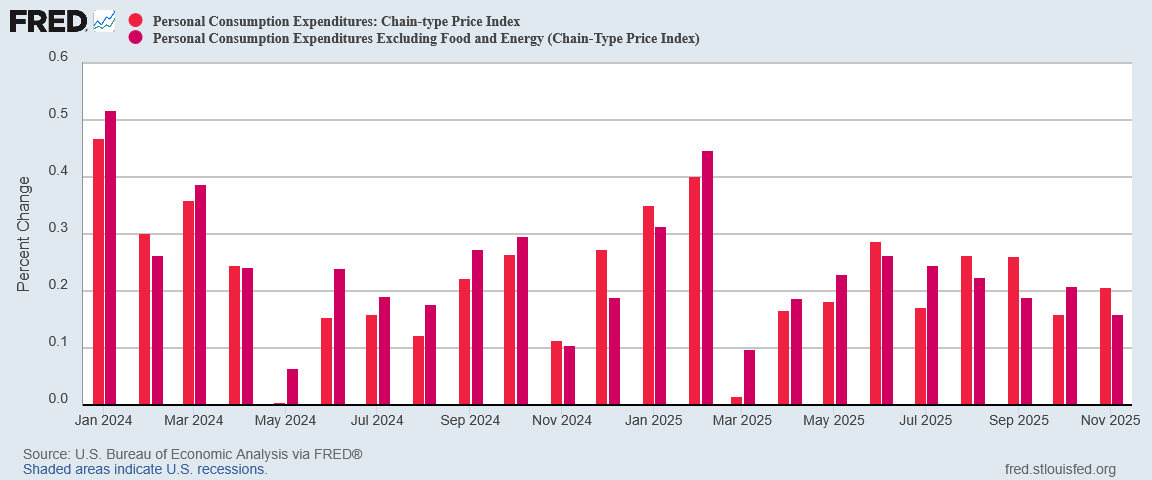

From the preceding month, the PCE price index increased 0.2 percent in both October and November. Excluding food and energy, the PCE price index also increased 0.2 percent in both months. (Refer to “Technical Notes” below for information on how BEA imputed missing BLS October prices.)

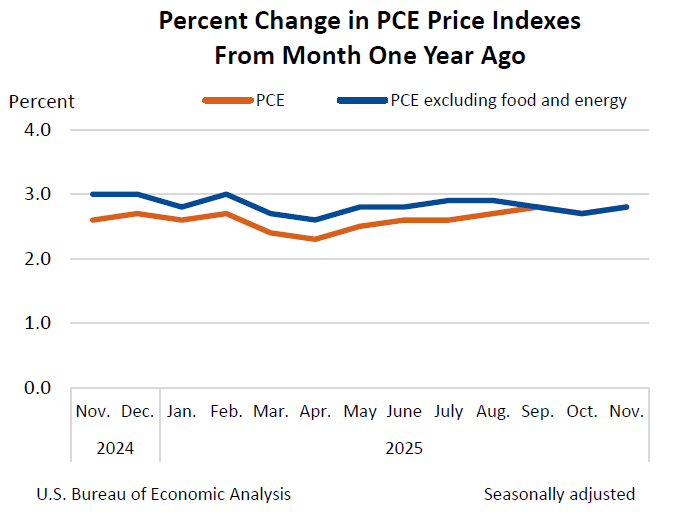

From the same month one year ago, the PCE price index increased 2.7 percent in October, followed by an increase of 2.8 percent in November. Excluding food and energy, the PCE price index also increased 2.7 percent followed by an increase of 2.8 percent.

There was not a lot of change in either the headline or core inflation rates, with both ending in November just slightly lower than where they were in September.

September was another month when the PCE report largely mirrored the earlier Consumer Price Index data. October and November were continuations of that pattern.

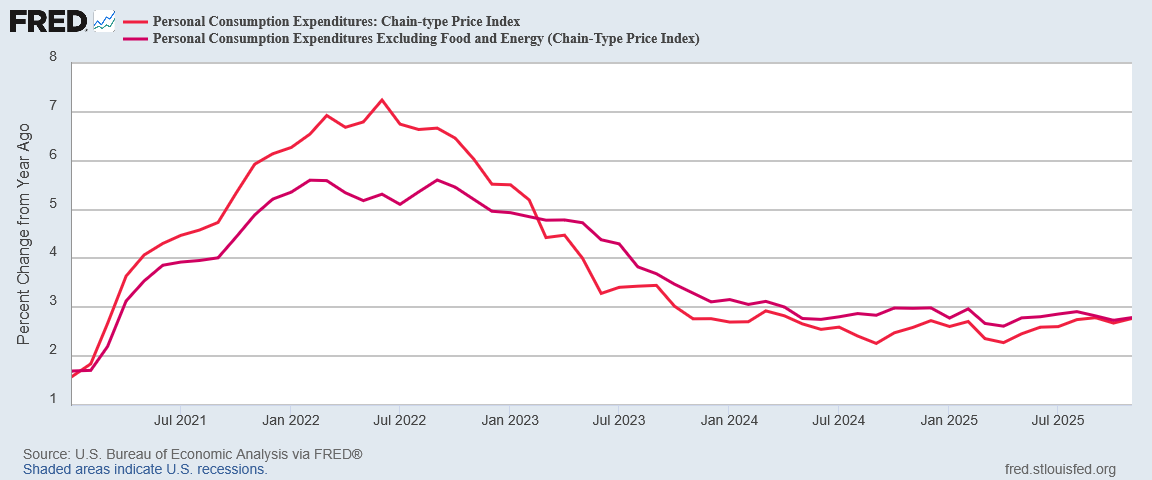

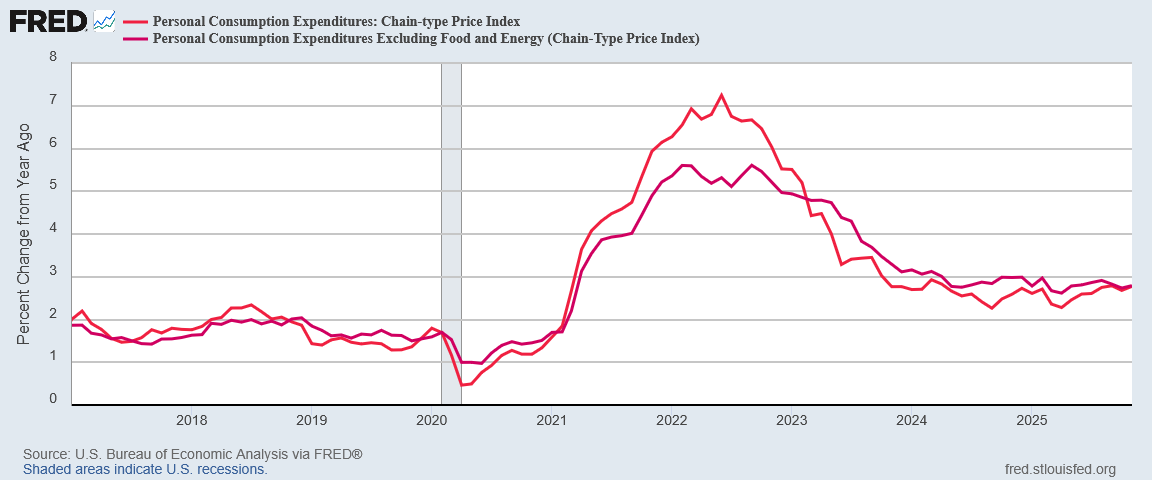

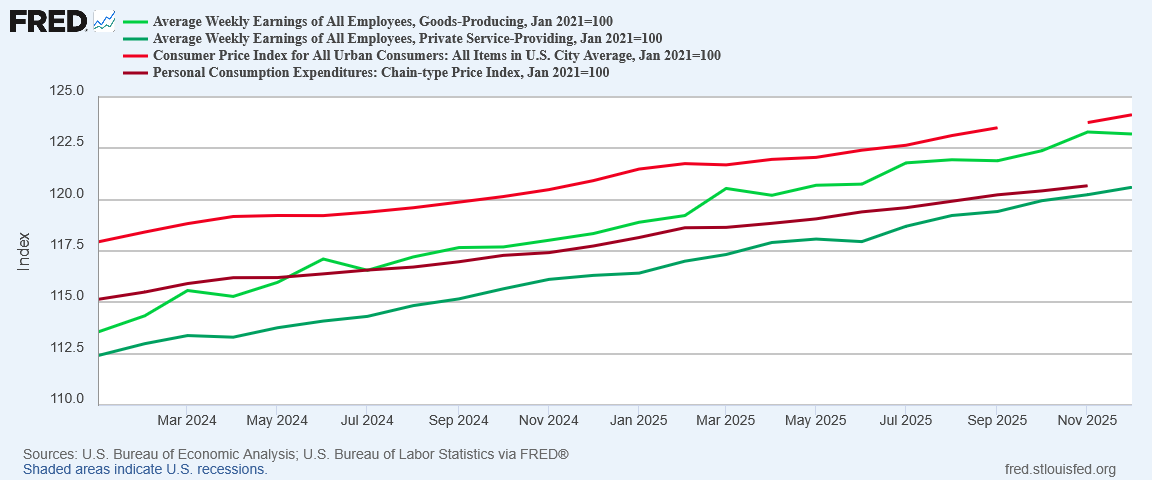

While this lack of change is disappointing to those who are hoping that inflation will eventually reach the Federal Reserve’s “holy grail” figure of 2% year on year, inflation stabilizing even in a 2.5%-3% range, slightly higher than it was before the COVID Pandemic Panic in 2020. If wages should rise faster than 3% year on year, prices across the board will gradually become more affordable.

With headline and core inflation metrics all showing that a long-term equilibrium inflation rate has been reached, we appear to be moving into an economic phase where inflation concerns should begin to fade, and wage concerns take on increased significance. We appear to be moving into an inflation “winter”, where other cost concerns such as wages take on greater prominence vis-a-vis inflation.

The good news is that prices are stable.

The challenge is that wages and income need to grow in 2026. Whether President Trump’s policies will rise to that challenge will be the question for the coming weeks and months.

Inflation Has Been Stable

The primary takeaway from the headline PCE inflation data is the stabilization trend. Year on year, neither headline nor core inflation rates have moved much recently.

While 3% is definitely higher than 2%, both headline and core inflation have been hovering in a range approximately bounded by 2.5% on the low end and 3% on the high end.

We see a similar trend month on month, where the changes have been in a definitive shrinking trend for most of the year, which has been itself a resumption of a longer-term downward trend since the beginning of 2024.

With smaller month on month changes, the year on year inflation trend has flattened out. The year on year rate is on a higher plane than it was prior to the COVID Pandemic Panic, but the stability is clearly present.

While a lower inflation rate would be undeniably preferable, the lack of major volatility, even at a higher year on year percentage rate, is at least somewhat encouraging.

Energy Is Up, Food Is Down

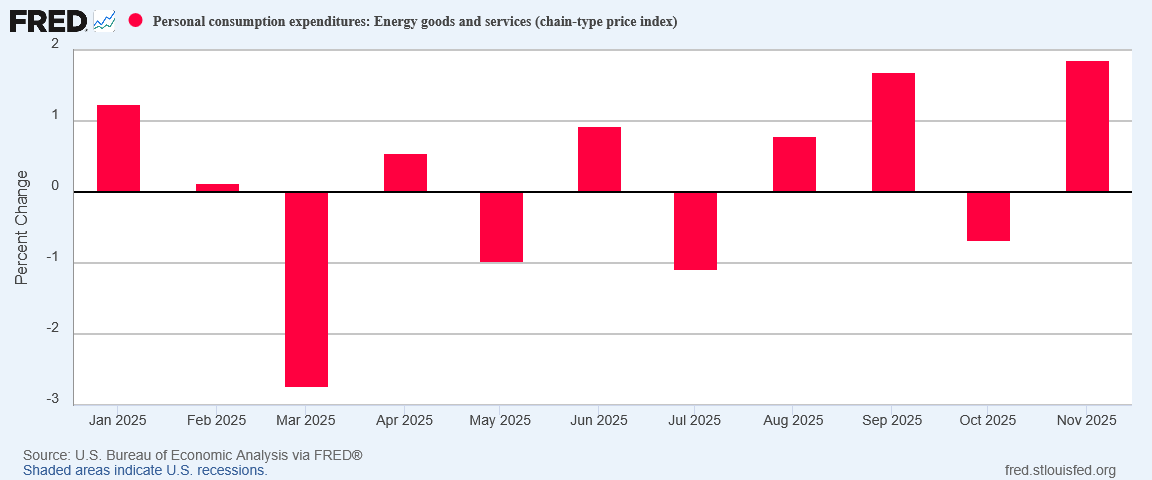

In what is perhaps the clearest sign of the geopolitical times, energy price inflation is one area that did advance in November, despite retreating in October.

With a volatile situation likely still simmering in Iran, and President Trump’s recent regime change flex in Venezuela, we should not be surprised that energy is reflecting much of that volatility.

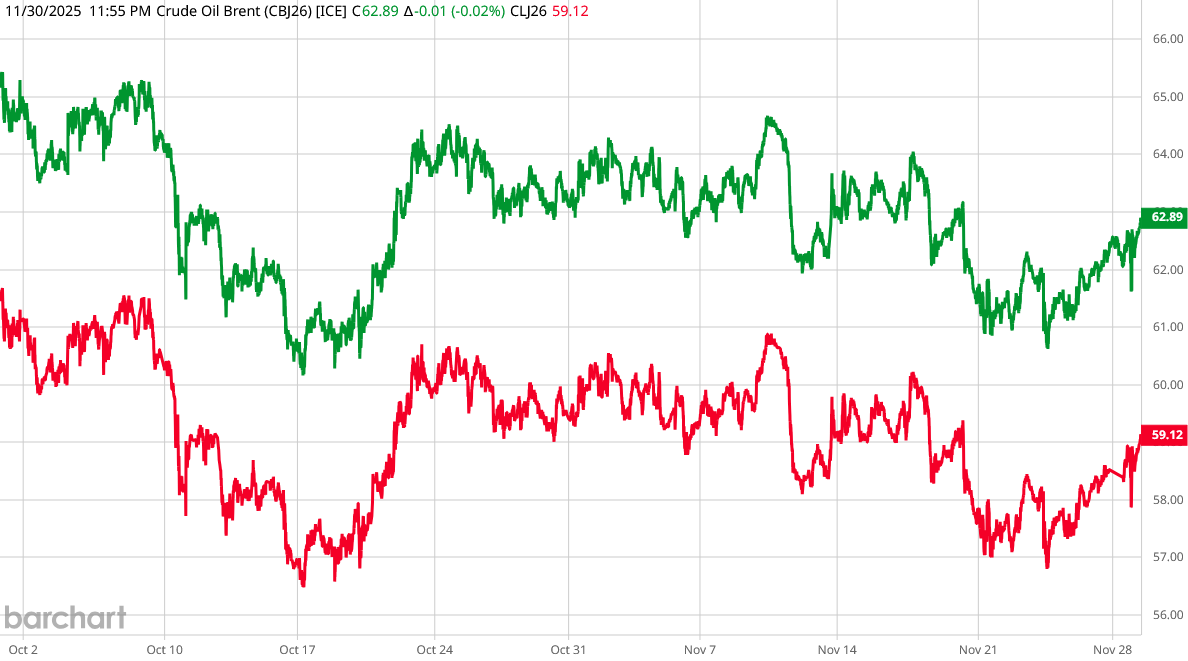

We see some of that volatility just in the benchmark prices for Brent and West Texas Intermediate crude, where prices dropped significantly in both October and November, only to recover again relatively quickly.

Will rising benchmark oil prices result in greater overall energy price inflation? They may.

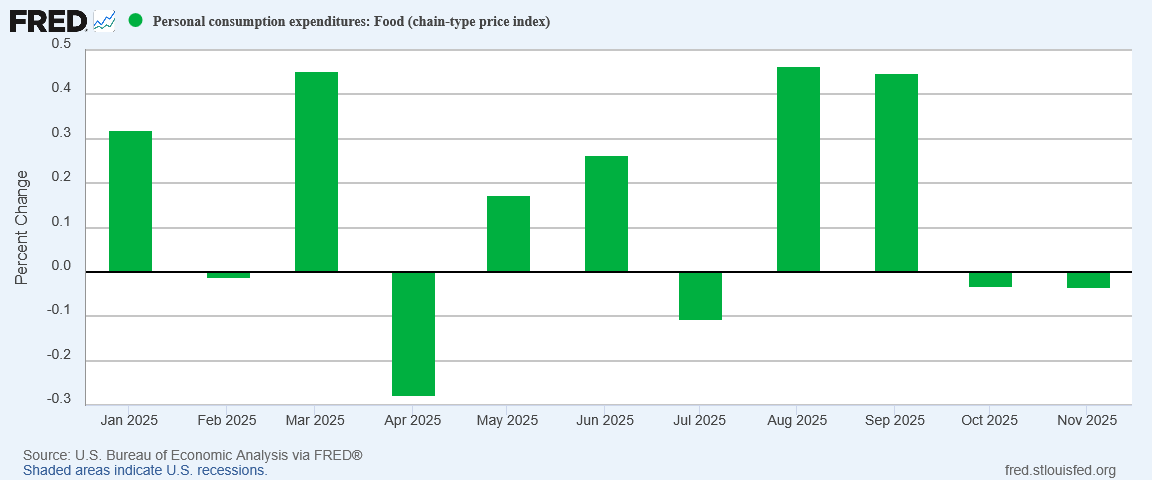

Yet if energy is showing more volatility, food—the other price sector excluded from core inflation metrics because of instability—is showing less volatility month on month for October and November.

Falling food prices would definitely help build a winning “affordability” narrative for the Trump Administration. For the past two months, the PCE Price Index data is showing exactly that deflationary trend in food prices.

As a general rule, energy and food prices are the most volatile, which is why they are excluded from the core inflation rate. From a perspective of emphasizing “affordability”, the diminished volatility that we are seeing in energy and food prices is undeniably encouraging.

Goods And Services Also Showing Little Change

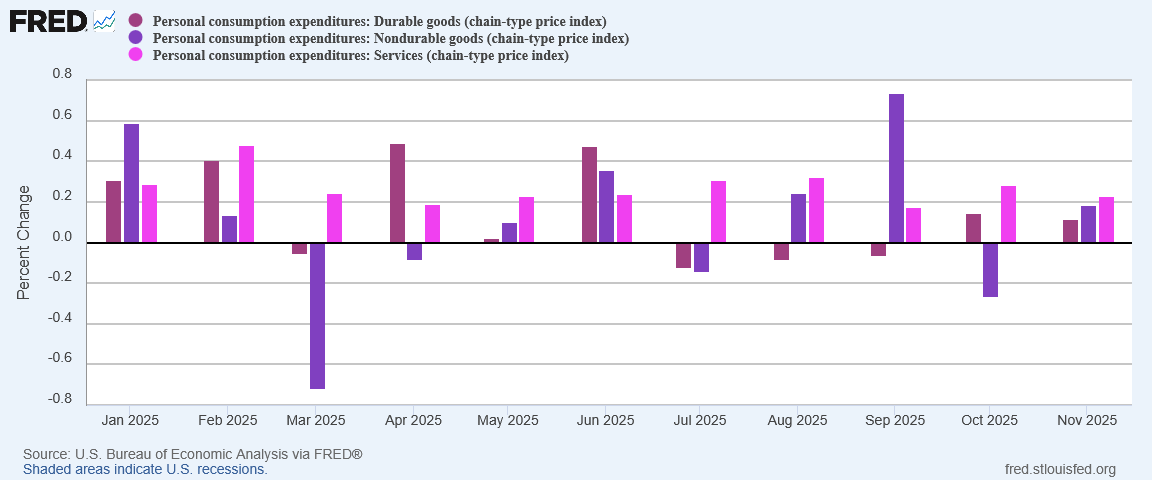

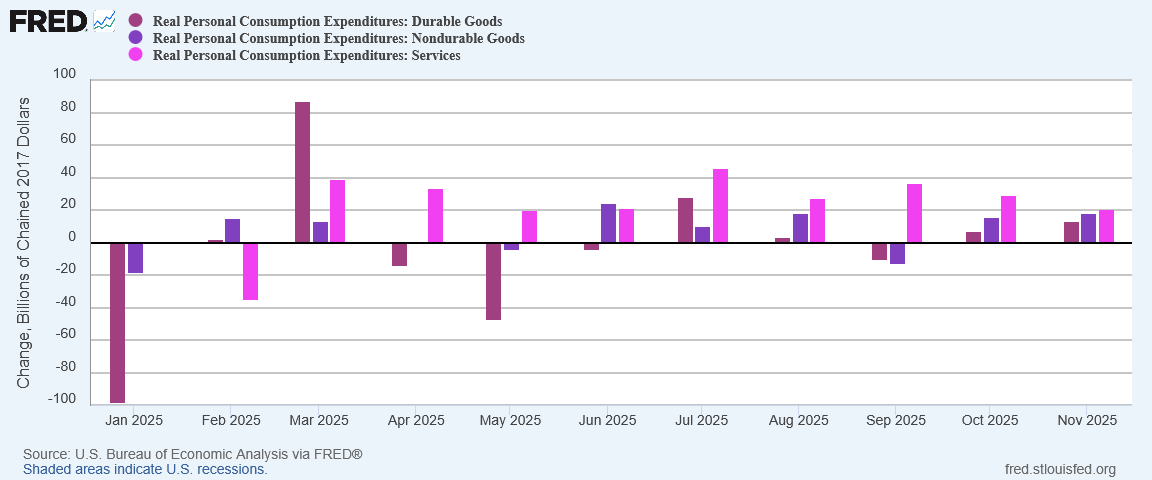

The stabilization trend is apparent even when we drill into core inflation metrics and start scrutinizing goods and services.

Month on month, November saw some of the smallest changes in goods and services prices.

While durable goods are showing an uptick in inflation after several months of printing deflation, the magnitude of the increases are smaller than they were at the beginning of 2025.

Non-durable goods are likewise showing smaller changes in November than they did at the beginning of 2025.

Services have been printing smaller changes month on month for most of the year.

The one aspect of this diminishing volatility in goods and services inflation which is a potential cause for concern is that there is also diminishing volatility in consumption levels month on month as well.

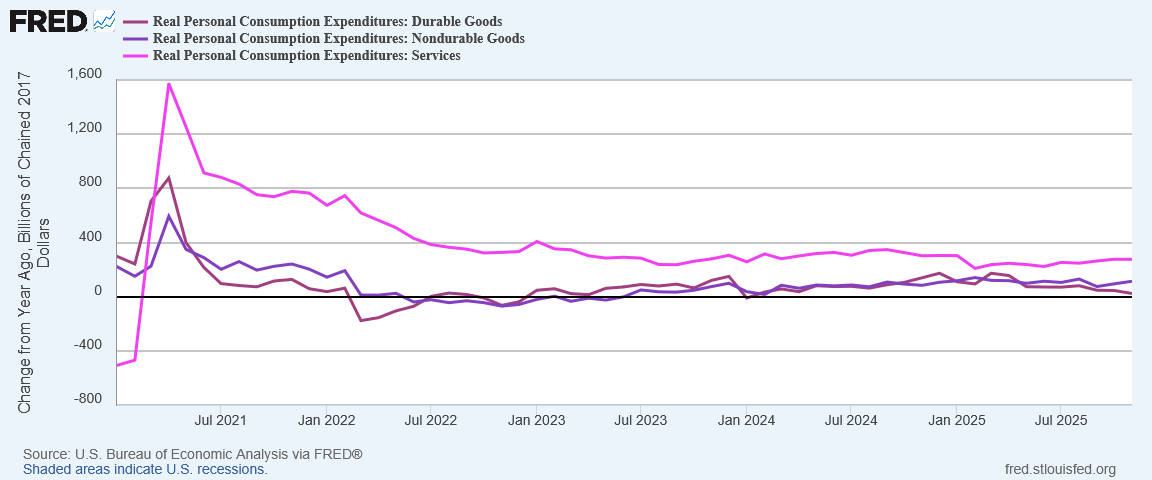

That flattening of the trend line extends to year on year comparisons as well.

Does the flattening out of consumption growth trends portend a lack of future economic growth? Is this a stagflation or even a deflation signal forming?

That possibility cannot be dismissed, particularly with the year on year changes in goods consumption slipping uncomfortably close to zero, making future declines in consumption expenditures not just possible but increasingly probable.

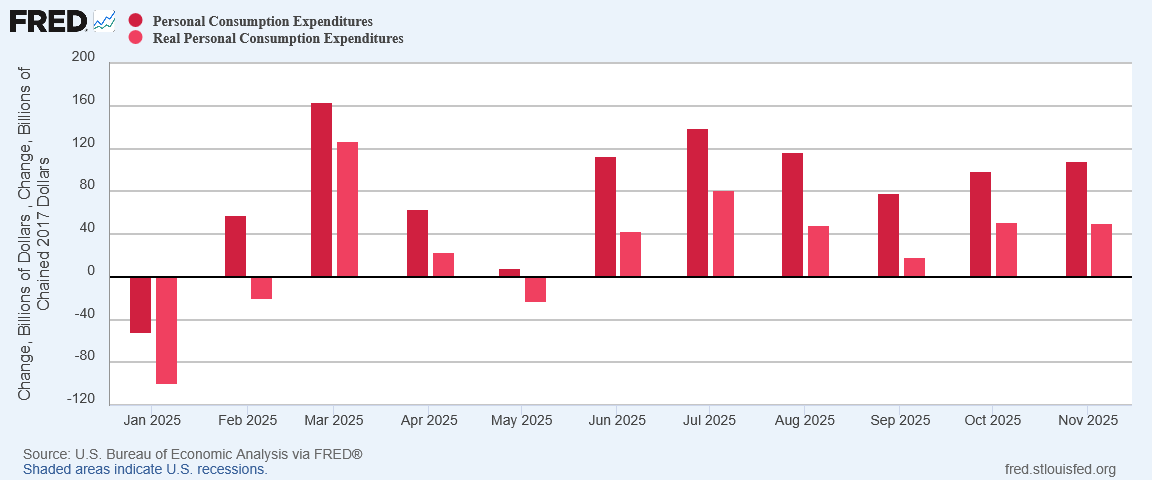

The stagflation concern is raised again when we consider that inflation rates are a larger portion of increases in nominal consumption levels relative to real consumption changes.

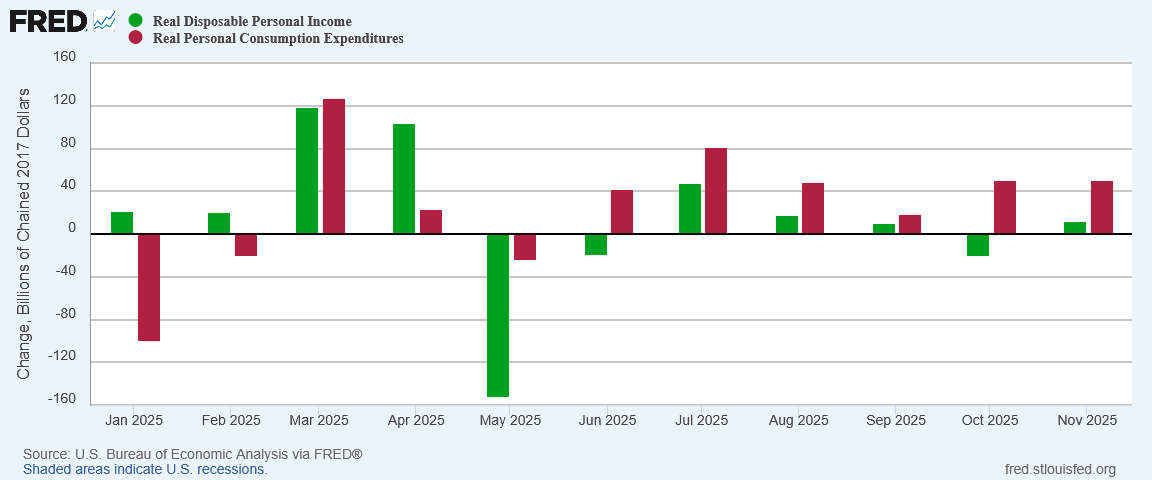

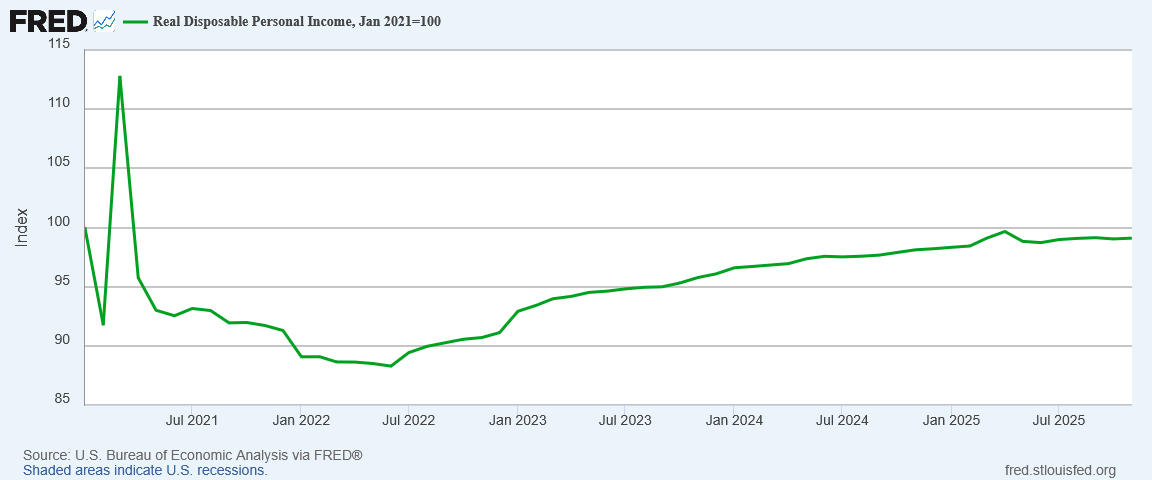

Further fueling these concerns is the fact that consumption continues to outpace disposable income.

When there is minimal change in disposable income levels, volatility in consumption levels is going to be likewise constrained.

That is the one downside in the Personal Consumption Expenditures data: relative to inflation wages have lost a little ground.

This concern is driven home by the reality that Real Disposable Personal Income remains below its January 2021 levels, and did not show any significant growth in 2025.

Without significant growth in Real Disposable Personal Income, President Trump’s economic “Golden Age” will not be felt by the broad swath of wage-earners and consumers in this country.

Winter Has Arrived For Consumer Prices?

While wage growth and disposable income growth are very real concerns, there is no denying that this latest inflation data from the BEA offers further confirmation that we are seeing broad price stability in this country.

In a different political climate, the Federal Reserve would be taking victory laps over this reality, as price stability is one of the Fed’s primary objectives with monetary policy.

In a different political climate, the Federal Reserve would also be more willing to admit that President Trump’s Liberation Day tariffs have not resulted in elevated inflation rates, despite the repeated insistence from many economic “experts” that tariff-driven inflation was just around the corner.

However, while the degree to which the two are intertwined will forever be a source of debate among different schools of economic thought, the reality of the US economy is that, while consumer prices have stabilized, real disposable income has also reached something of a plateau. If there is to be meaningful economic growth in this country, real disposable personal income has to grow. That did not happen in 2025, and that’s a problem.

Does that mean that the US is heading into a stagflation scenario, and perhaps another “lost decade” of minimal or sub-par economic growth? That possibility cannot be dismissed. Perversely, inflation and volatility are also indicators of a certain amount of dynamism in an economy, which is necessary if there is to be any significant economic growth.

Still, the reality of the data at present is that we are not seeing inflation heating up at all, let alone significantly. Inflation is cooling and not heating up. Whether that means winter is still coming for inflation or that it means winter is actually here depends largely on how far one wishes to carry the metaphor.

For the Trump Administration, that broad price stability is an established norm is both a blessing and a challenge. The blessing is, of course, that there is broad price stability. The challenge is that, without disrupting that price stability too much, real disposable personal incomes need to be pushed upward, if only to get them back to where they were in January 2021.

President Trump’s economic policies have not focused on wages or real disposable personal income thus far. Hopefully, that will change in 2026. Wage and income growth against a backdrop of price stability would bring President Trump’s vision of an economic “Golden Age” closer to more Americans.

Price stability is very much the good news to come out of the Personal Incomes and Outlays report.

Wage and income growth is the challenge embedded in that report for 2026.

Thank you for a grounded view, Peter. There are three other factors regarding wage and personal income growth that I have not heard discussed much in recent times.

One is that the percentage of the population dependent upon government assistance has soared during my lifetime. Their personal income increase is only a small amount which doesn’t really keep up with inflation. The second factor is that the majority of Boomers have retired now, and their Social Security increases likewise don’t completely keep up with inflation. (The government “says” it indexes for inflation, but sorry, the additional $32 per month I’m getting is NOT cutting it at the grocery store!)

The third factor is that close to half of the Boomers have not retired in a good financial position. I don’t know what the current percentage is, but the figure I heard several years ago was that 45% of Boomers have not saved anywhere close to enough in order for them to retire. And I mean, they cannot retire, and have to continue to work at least part time in order to just pay food and rent. The reality is that those Boomers who inherited money or who were quite financially successful can retire, but the rest are struggling with making ends meet.

So these factors will complicate Trump’s Golden Age goals. It’s going to be very hard to increase the standard of living for a huge percentage of the American population. Peter, can you see any solutions to this? (If so, the White House will be calling you soon!)