In my last article, I highlighted the importance of information in combating the emerging disease COVID-19, also known as "coronavirus". For any person coping with this disease, either on a personal level or as part of a larger organization, information is the best tool for organizing resources, establishing action plans, and making appropriate preparations.

Priority number one must always be "gather more data", and priority number two must always be "share all data."

Priority number three must always be "keep data current."

Several events of the past few days have served to highlight the importance of gathering and sharing information, as well as providing more current data that must be acknowledged.

Washington State: Coronavirus Takes Hold

Snohomish County in Washington State took center stage in the COVID-19 pandemic narrative last week, with the detection of coronavirus case "of unknown origin". As the individual had no known travel history to one of the disease epicenters, he had presumably acquired it in the community--but where and from whom was a mystery.

“It’s concerning that this individual did not travel, since this individual acquired it in the community,” Washington state health officer Dr. Kathy Lofy told reporters Friday. “We really believe now that the risk is increasing.”

As might be expected, this news touched off a considerable amount of anxiety in the area, as people took to social media to express their concerns and vent their frustations.

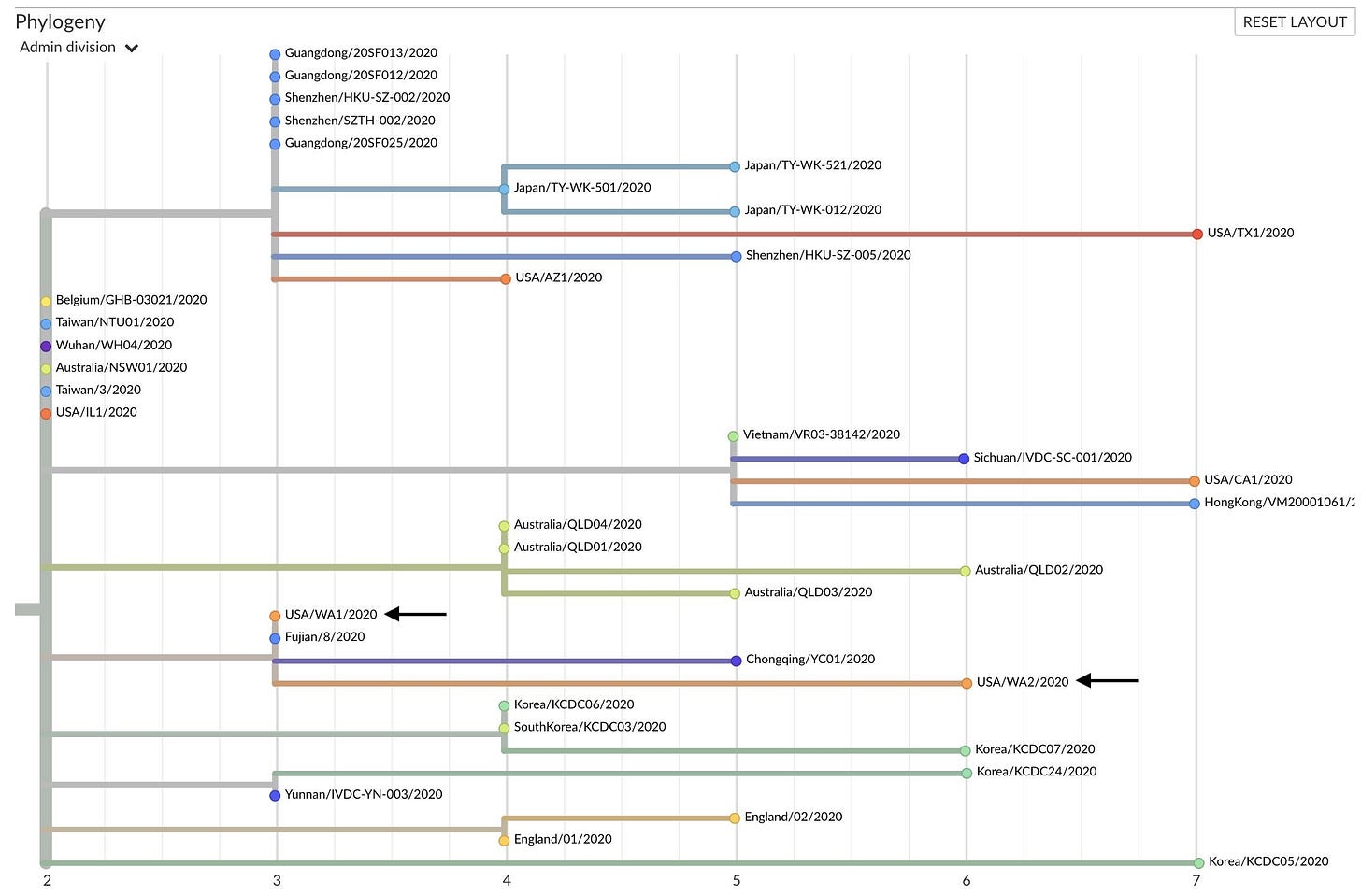

One of the most disturbing aspects of the Snohomish County infection was the apparent genetic similarity to the first COVID-19 case in Washington State, generally termed WA1 (with the new infection being WA2).

An inference was put forward that local endemic transmission--i.e., "community spread"--had been taking place since the first patient in the state had brought the disease back from China. Moreover, if that were true, it would indicate there were a considerable number of COVID-19 carriers in that part of the state, each of whom could infect others, spreading the disease far and wide.

The legacy media dutifully began hyping the phrase "community spread" almost immediately, completely ignoring the reality that, at the time, community spread had not been established. A single case of unknown origin does not establish endemic transmission. Disease spread always requires at least two people: one to give the disease and one to get the disease.

That error was short-lived, as community spread was unequivocally established later that day, when COVID-19 was detected in a Life Care Center nursing home in neighboring Kirkland County. This quickly became the focal point of reporting on COVID-19 in Washington State, as facilities like Life Care Center have significant concentrations of elderly and infirm residents, the very populations most vulnerable to the severe form of COVID-19 infection.

The detection of coronavirus in the nursing home served to amplify fears that COVID-19 was rampant in the community, and that it had been spreading via "cryptic transmission"--a fancy way of saying COVID-19 supposedly had been infecting people without anyone noticing. As would become apparent, the legacy media once again remained two steps behind the disease, and once again got the trajectory of the disease wrong. There was no "cryptic transmission" of the virus for weeks on end.

How do I know this? I know this because the Washington State Department of Health has established this, through the very mundane but reliable auspices of their Weekly Influenza Update report. I know this because the data tells us this.

A quick review of the Week 8 Report (archived for reference) revealed one interesting trend: emergency room visits for Influenza Like Illness had been declining since the beginning of January. Washington State was not seeing any cryptic transmission certainly into the middle of February--if there had been much transmission of the virus, there would have been an increase in ER visits and subsequent hospitalizations. If people are not going to the ER with "flu-like symptoms", either they are not sick or they are not all that sick. Either outcome--categorically established by the Week 8 report--works against the presumption of widespread cryptic transmission for weeks on end.

I shall reiterate something I have said before: I am not making any comment on the medical aspects of the disease itself. I am looking at the data purely from the perspective of crisis management. People, businesses, and communities are faced with the distinctly non-medical challenge of organizing their various resources in response to this pandemic, and doing so properly means recognizing how and when risks of exposure shift.

Washington State: People Do Get Sick

As it turned out, as the COVID-19 cases began to accumulate people were going to the ER to seek medical treatment. In the Week 9 report, the decline in ER visits in several parts of the state abruptly reversed, including in and around Seattle. At the same time the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases began to rise in Washington, so too did the number of ER visits with Influenza Like Illnesses (ILI).

The significance of the Week 9 rise in ILI visits is that it confirms the lack of cryptic transmission from mid January through early February Contrary to the breathless hype of the legacy media, there was no legion of undetected cases spreading disease across Washington state. Significant spread of COVID-19 did not start to occur until the latter part of February.

How can we be sure of this? We can be sure because with or without coronavirus testing, coronavirus infections proceed on their usual timeline. Viruses do not wait on the pleasure of CDC test kits to propagate, or to make people ill. Coronavirus is no different. As the World Health Organization documented in "Report of the WHO-China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)", COVID-19 incubates for just under a week on average, before emerging with classic "flu like" symptoms.

People with COVID-19 generally develop signs and symptoms, including mild respiratory symptoms and fever, on an average of 5-6 days after infection (mean incubation period 5-6 days, range 1-14 days).

It is irrational to believe that people in Seattle would have delayed going to the ER or to their doctor once they began to present with symptoms. Therefore, we can safely project that the people presenting with new influenza-like illness in Seattle's emergency rooms during the last week of February were infected with the disease the week before, or at most two weeks before. Even though there have been reports of longer incubation periods, the vast majority of cases appear to incubate within the 1-2 week timeframe (certainly, that is the information being provided by the WHO and the CDC).

If there had been any significant cryptic transmission of coronavirus in the Seattle area between January 19, when the first COVID-19 case was confirmed, and roughly fourteen days before February 29, when the second case in Snohomish County was confirmed, there would have been an earlier spike in ILI ER visits. There were not, as has been alleged on social media, "thousands" of people in the Seattle area infected with coronavirus undetected for weeks at a time. The significant spread did not begin to occur until the middle of February.

Additionally, the Week 9 report data shows that not every part of Washington state is seeing significant cases of COVID-19. Where ILI visits are declining, there are not large numbers of coronavirus cases thus far. That may change, and probably will change, but tracking the spread of any disease means noting both where it is and where it is not.

Still Not Enough Tests

As I noted previously, the CDC's announced goal of having 75,000 test kits available was and is a farce. They should have aimed for ten times that number, and they should be aiming even higher now. No amount of proxy disease metrics are going to eliminate the need for accurate diagnostic testing. We should always demand the best and the most accurate data.

However, today's logistical reality is that there are not enough tests--particularly in Kirkland County Washington. There, at least, the inevitable has happened: COVID-19 is now endemic among the general population. The widespread transmission that was not happening in early February is going to begin happening now in early March.

Amazingly, the CDC's response to that reality has been to stop most testing, according to Evergreen Hospital. That is a questionable decision at best, and sheer lunacy at worst. Refusing to gather information is never a right response in any crisis. Judicious use of scarce test resources is what is needed, not refusing to use them--which appears to be what the CDC has done.

As of March 3, 2020, we have halted performing nasopharyngeal testing in our outpatient clinics, including all five urgent care locations.

There is no mention in that announcement of testing criteria or protocols to be used in lieu of nasopharyngeal testing. That is irrational--it is not possible to screen for a disease without having a means to confirm the disease. Without a test, it is not possible to distinguish between COVID-19 and other cases involving general "flu like" symptoms.

Testing is essential, no matter how much other data is available. Communication about testing is not merely essential, it should be considered a moral imperative. People need information, and people deserve to get all the information, including what the CDC plans to do about testing.

Use All The Data

Given that there are not enough tests to test everyone with flu like symptoms, and given the reality that no disease waits on a test kit from the CDC, it is essential that people use all the data available to them. This means looking beyond coronavirus test results and numbers. Every state and most localities maintain a weekly influenza update report like the ones generated by the Washington State Department of Health. While coronavirus is unequivocally not influenza, the influenza reports track the entire range of "influenza like" illness--hence the acronym "ILI". As the Washington State reports demonstrate, there is a correlation between levels of ER visits for influenza like illnesses and prevalence of COVID-19 in a community.

Because these reports are available for public consumption, they are a resource anyone can use to see where the disease has likely taken hold, and where the disease has yet to do so. People can see this for themselves, and I encourage everyone to become familiar with these reports for their state and community. Know the general state of infectious disease in your community.

This background information allows people to take the proper steps to mitigate their risks at the proper time: if COVID-19 has yet to take hold and the risk is low, planning and preparation are key; when the disease does arrive, shifting to more direct responses, such as social distancing, becomes appropriate. Husbanding various resources (for the individual household, this includes all the basic necessities such as non-perishable foods) during the low-risk phase enables people to prevail through the high risk periods.

The importance of this background information is that it does not rely on test kits which may or may not come from the CDC, and may or may not work. This is data that we already have, data that is already tracked. While this data will not tell us who has COVID-19 or precisely how many people have COVID-19, it will tell us where the disease is most active. As the influenza report data changes it will tell us where the disease is becoming active (and, eventually, where it is dying down). It will tell people what their relative risks are and how those risks are changing.

It will also indicate where hospital systems are likely to be under stress and strain. The challenge of any infectious disease is not merely the disease itself, but its capacity to overwhelm healthcare infrastructures and consume scarce resources. A hospital filled with COVID-19 patients will face greater challenges caring for trauma patients, cancer patients, and all the other patients hospitals serve regularly. Planning and preparation includes thinking about not just COVID-19, but how to care for and manage all health conditions. People with chronic conditions need to update their care plans to include what to do if the local hospital becomes overwhelmed. Doctors need to be thinking about how to treat all their patients under such circumstances. First responders need to be conversant with which hospitals may go on diversion status and which alternate hospitals can take patients in need of critical care.

Dealing with COVID-19, as with any crisis, begins with planning and preparation.

Plan Now. Prepare Now.

People, businesses, and communities not dealing with high numbers of COVID-19 cases (which, thankfully, is still most of the United States), need to plan and prepare now for COVID-19 outbreaks. Assume they will come, and assume that the levels of disease in Seattle will be the levels of disease in every outbreak.

For people: stock the pantry with nonperishable foods, and lay in a store of disinfectants and disinfectant wipes. Recognize that, in a panic, stores are quickly emptied of such things. Having a few days to a few weeks of food on hand now will remove the need to do battle with the crowds later. Gathering such supplies now will also put less strain on local area stores, as they will have time to restock and resupply. Being able to remain at home once the disease appears in the community will protect the individual and serve to slow the spread of the disease--the reason such "social distancing" works is that if a disease cannot infect new patients it will eventually die down. Every day people avoid the disease reduces the disease that much more.

For businesses: Make plans to have people work from home. Where feasible, consider instituting such plans now. In all cases, be extra rigorous in cleaning offices and work areas--starting the cleaning regimens now will deny COVID-19 surfaces on which to land later.

Use data such as the weekly ILI statistics to remain aware of when it is time to move from a planning and preparation posture to an active implementation of those plans.

Above All, Don't Panic

The phrase "Don't Panic" cannot be said enough right now, especially since the legacy media is doing an outstanding job of telling everyone the exact opposite. Do not be seduced by the argot manufactured by the media. Do not be swayed by salacious (and largely misleading) headlines. Focus on the data. Focus on the facts.

Know the state of infectious disease in your community. Know how it is changing. Having that background data will allow you to determine if a report of COVID-19 in your area is a sign of impending outbreak or an outbreak in full flower.

When the outbreak comes, have a plan, and use that plan.

Be mindful of this much: fear is always a response to the unknown. We fear what we do not know, but what we know we generally do not fear. The way to combat fear is to know as much as possible. The way to prevent panic is to be informed and to keep others informed. Use all the data available, and seek out more data where possible. Do not hyperfocus on any one data set. Consider all the facts, not just a few.

Follow the data. Forget the headlines.