Inflation Is Going To Get Worse. But How Much Worse?

Pundits Predict 9%. We Should Be So Lucky

Economic and finance prognosticator (in other words, a money “expert”) Mohamed El-Erian made an easy call on Face The Nation yesterday when he predicted inflation would get worse.

With all the negative economic data swirling around, that’s like predicting summers in Texas will get hot.

The real question that needs to be answered is “how much worse will inflation get?” El-Erian does not have a good answer to that, although his idea of “worse” seems to be inflation hitting 9%.

"There was hope initially, that it is transitory, meaning temporary and quickly reversible. There was hope, as you pointed out, that it had peaked. I never shared those hopes. I think you've got to be very modest about what we know about this inflation process. And I fear that it's still going to get worse, we may well get to 9 percent at this rate."

If inflation only rises to 9% over the near term, we should count ourselves lucky. If we peer into the future of global inflation, the global trend suggests inflation getting much higher than that.

Peering Into Future Inflation: The Producer Price Index

The prevailing tool for “looking ahead” on inflation is the Producer Price Index. Much like the Consumer Price Index, it measures overall prices for various goods and services in an economy. The key difference is that the PPI measures the prices domestic producers receive for goods and services, while the CPI measures the prices consumers pay.

The two indices are structurally different because the PPI measures prices at the first sale transaction to the producer, while the CPI measures prices at the last sale transaction to the consumer. Additionally, the PPI components are markedly different from those making up the CPI.

The PPI often measures prices based on the first commercial transaction for a product or service, in contrast with the CPI's focus on the final sale. But the two don't just differ based on the type of prices measured. There are also important compositional differences between the PPI and the CPI based on what's included and left out.

For example, the PPI does not measure price change for aggregate housing costs, while the CPI's shelter category including the imputed owners' equivalent of rents accounts for one-third of the overall index. Meanwhile, the PPI incorporates a weighting of nearly 18% for health care products and services not far off the sector's weight of nearly 20% in the U.S. Gross Domestic Product (GDP). In contrast, because the CPI does not measure third-party health care reimbursements, its weighting for medical care is below 9%.

Because of where the PPI measures prices for goods and services, it generally acts as a leading indicator for the CPI—an upward trend in the PPI is generally followed by a similar trend in the CPI within a reporting period or two. Looking at the PPI and CPI for the United States since 2017, we can see that this is indeed the case.

Most notably, producer price inflation started rising right at the end of the 2020 COVID-induced recession.

(Note: while the percentage change in PPI was negative through the summer of 2020, the direction of the change was positive. Thus, the change in producer price inflation in May 2020 from April to -1.1% from -1.3% constitutes a rise in inflation—or a decrease in deflation—of 0.2% without seasonal adjustment even though the PPI itself continued to decline through August of 2020, after which the percentage change was positive.)

Consumer price inflation, on the other hand, ticked down another month before starting its climb.

Returning to the PPI chart, while producer price inflation year-on-year did seem to ease somewhat, from 11.5% in March to 11% in April year-on-year, it is still approximately 3 percentage points higher than consumer price inflation. On that basis alone we should expect significantly higher inflation—well above 9%.

However, when we look at the global picture, the outlook gets even grimmer.

Global PPI: The OECD Data

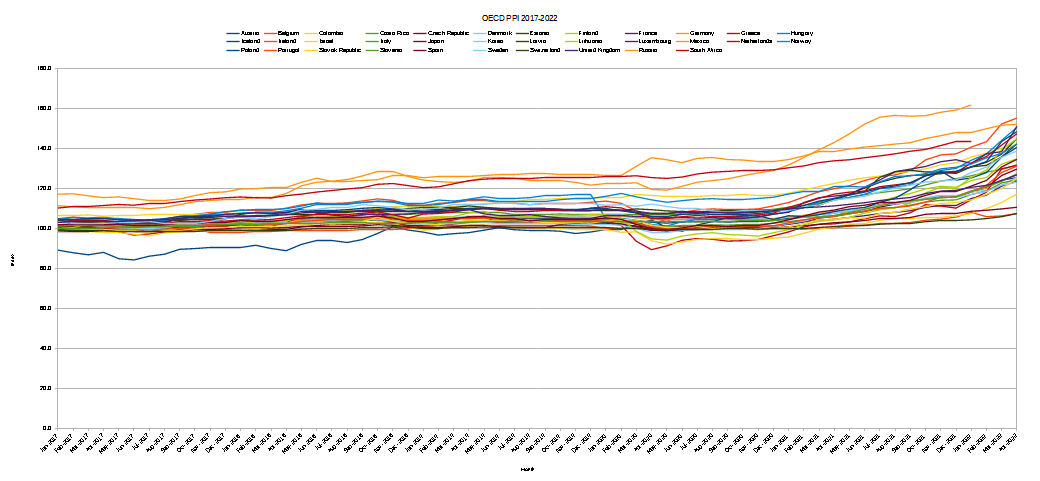

Just as the Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development tracks CPI data for a number of countries, it also tracks PPI data. The PPI statistics the OECD presents are not drawn from the same country list as the CPI, so a country-specific apples-to-apples comparison of PPI and CPI is not possible, but we can looks at the macro trends across the whole of the PPI data provided by the OECD.

The first thing to note in looking at the OECD data is, just as with the CPI, Turkey’s PPI is completly out of control, and has been for a number of years now. If there is one country that qualifies as an economic basket case based on inflation numbers, it is Turkey!

Yet even with Turkey’s PPI outpacing by far every other country captured by the OECD statistics, we can still see not just a rise in the PPI starting at the end of the 2020 recession, but a significant widening of the spread among the measured countries as we move forward to the present day.

If we screen out Turkey as an outlier we can see the spread more clearly.

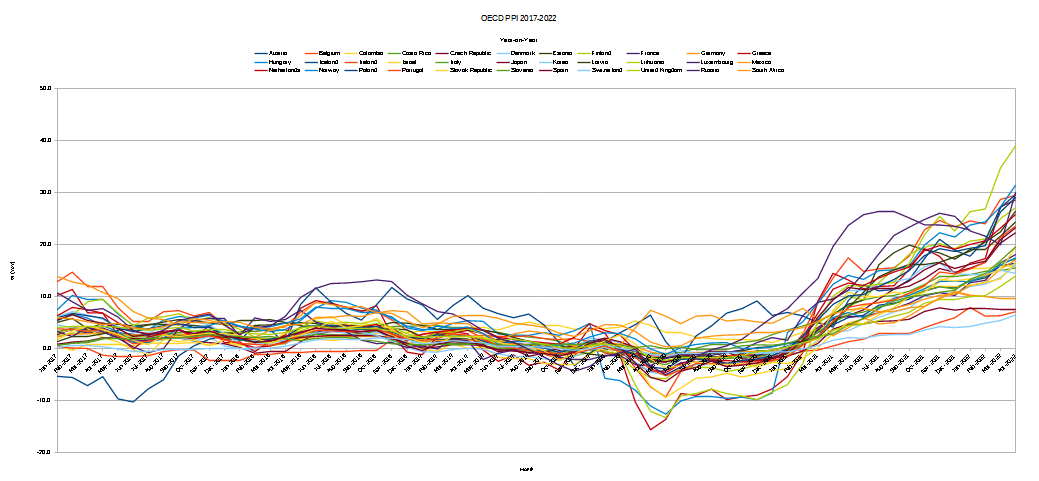

Even looking at the PPI directly, the forecast for future inflation does not look at all good. If we shift to a view of the percentage changes in the PPI—i.e., producer price inflation—we begin to see just how bad the future outlook is for inflation.

Not only do we see a broad rise in producer price inflation beginning within a month of the end of the 2020 technical recession for the US in April of that year, but the spread among the measured countries for April of this year is from a low of 6.4% for Switzerland to a high of 39% for Lithuania. Only four countries reported producer price inflation for April below 10% year on year.

Indicators Are Not Forecasts, But The Indications Are Still Grim

Remember, the PPI is a leading indicator for the CPI, and thus current producer price inflation is a leading indicator for subsequent consumer price inflation. A leading indicator is not a direct forecast, and so we cannot say, for example, that inflation in Lithuania is going to be 39% within the next month or so. What we can say, however, is that producer price inflation on a global basis indicates not just continued rise in consumer price inflation, but likely double digit consumer price inflation around the world.

Mohammed El-Erian’s off-the-cuff prediction of 9% inflation would be just below Mexico’s April producer price inflation. Nearly every other country whose PPI is recorded by the OECD is experiencing producer price inflation that is several digits at least above 9%.

If the PPI is any guide at all, the future for inflation is considerably worse than 9%, and potentially worse than even the 14% inflation this country experienced during the hyperinflationary period of the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Economists Are Predicting US Producer Price Inflation Will Rise For May

The US PPI report for May is due to be released by the Bureau of Labor Statistics tomorrow. The consensus view among economists polled by financial services firm Morningstar is for producer price inflation to come in at around 0.8% for the month, up from 0.5% recorded by the BLS for April.

With producer price inflation forecast to rise, and with global producer price inflation already well above 1% month on month—only two countries reported MoM PPI rises below 1% for April—El Erian’s 9% prediction for consumer price inflation sounds downright optimistic. If the monthly percent change in the PPI for the US is 0.8%, and inflation in the US is already at 8.6%, 9% will be likely within the next month or so.

Unless there is a downturn in producer price inflation very soon, consumer price inflation in this country, as in the rest of the world, will begin reaching historically record levels.

What the global PPI data tells us is that inflationary forces in the global economy are still quite strong and are highly likely to push inflation much higher in the months ahead.

The global recession is just getting started.

Read an article yesterday that said, by the old method used during the Carter Administration, Carter's high was 14.5% and Xiden has eclipsed that by roughly 2% at 16.5%.

PNK, "grim" is a hell of an understatement, we aren't looking at "inflation" but "collapse," globally! The differences in America in 2022 vs in 1978 is that we don't have the capacity to survive, with our "service economy." What idiot ever thought that was a good idea.

All tied to lockdowns and our stupid hysterical response to Covid. All of it.