There is no sugarcoating yesterday's inflation report. The release of December‘s CPI data starts bad and gets worse.

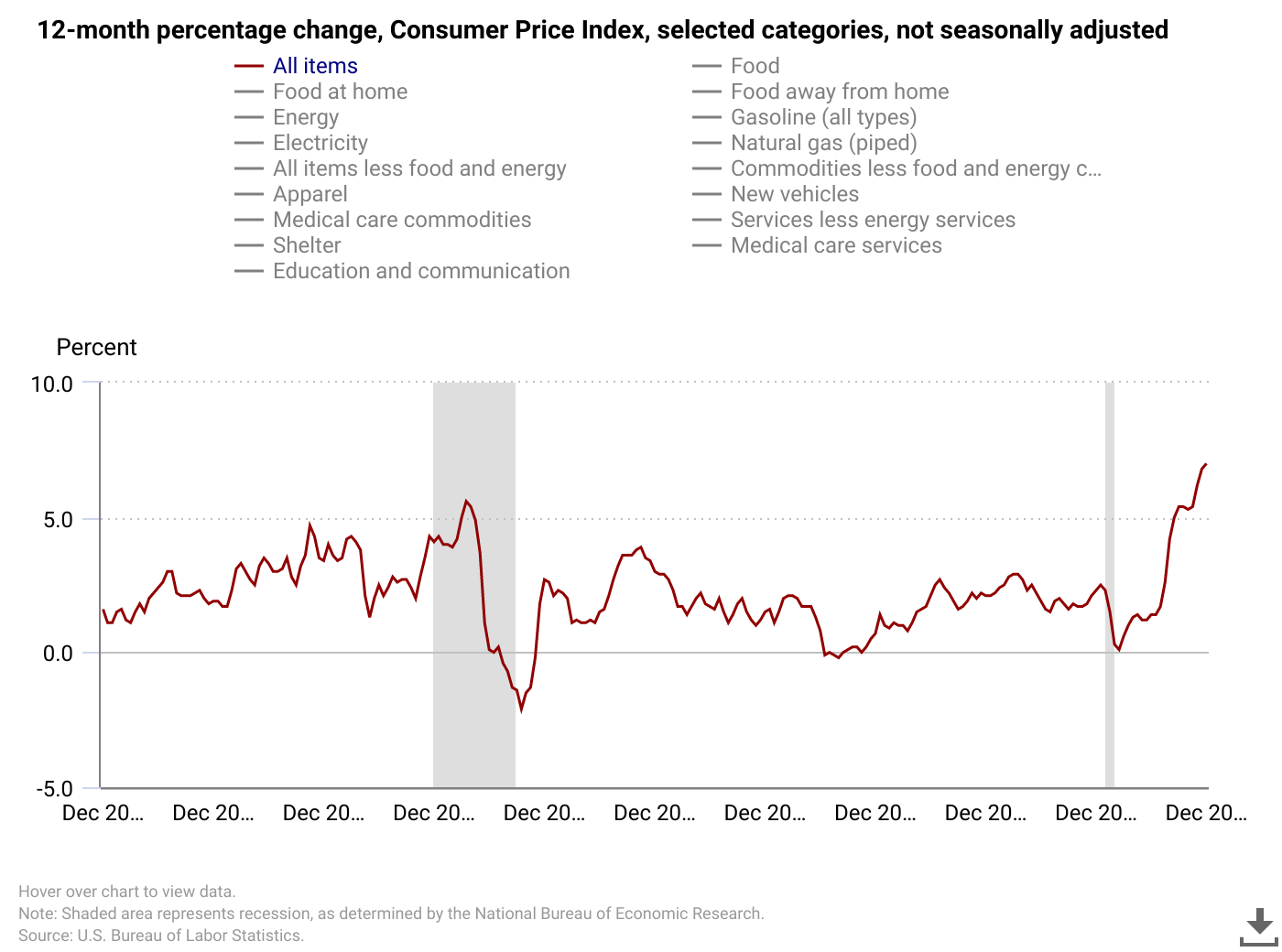

The Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U) increased 0.5 percent in December on a seasonally adjusted basis after rising 0.8 percent in November, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today. Over the last 12 months, the all items index increased 7.0 percent before seasonal adjustment.

After decades of “official” inflation well below 5%—and for much of that time below 2%—inflation is now between double and triple the average inflation most Americans have experienced in their lifetime. A 7% inflation rate is 25% above the previous inflation peak of 5.6% in July of 2008, in the middle of the 2008-2009 recession.

Coming on the heels of a COVID-19 lockdown-induced recession, 7% inflation is quite the dramatic surge.

Yet, as is so often the case with government statistics, the top level numbers mask a much more significant—and much more disturbing—reality. The 2020 lockdowns and the accompanying recession not only diminished the US economy, but distorted it to an alarming degree. To describe the current economic situation as “off kilter" is being optimistic.

Inflation Is Not Created Equal

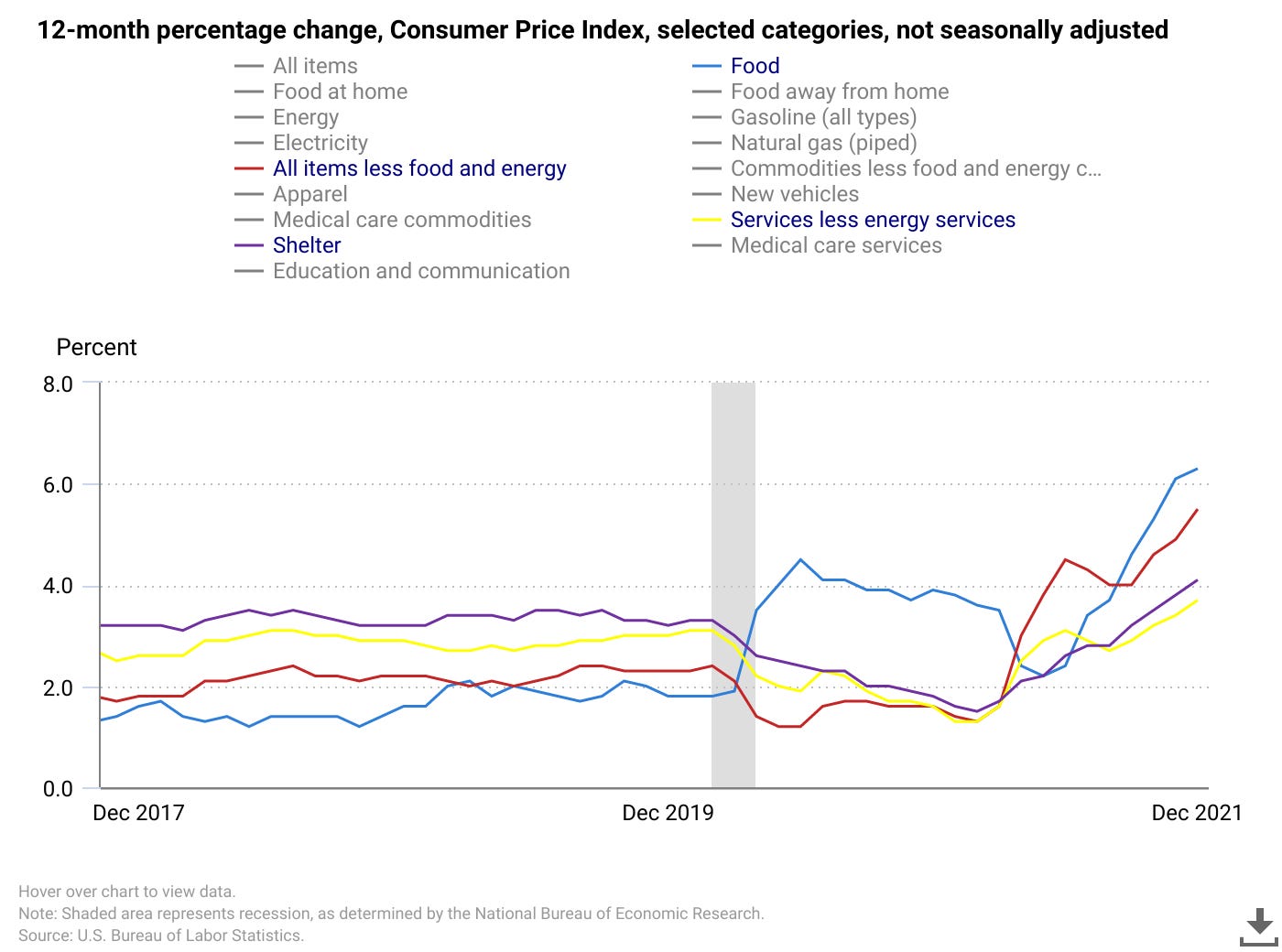

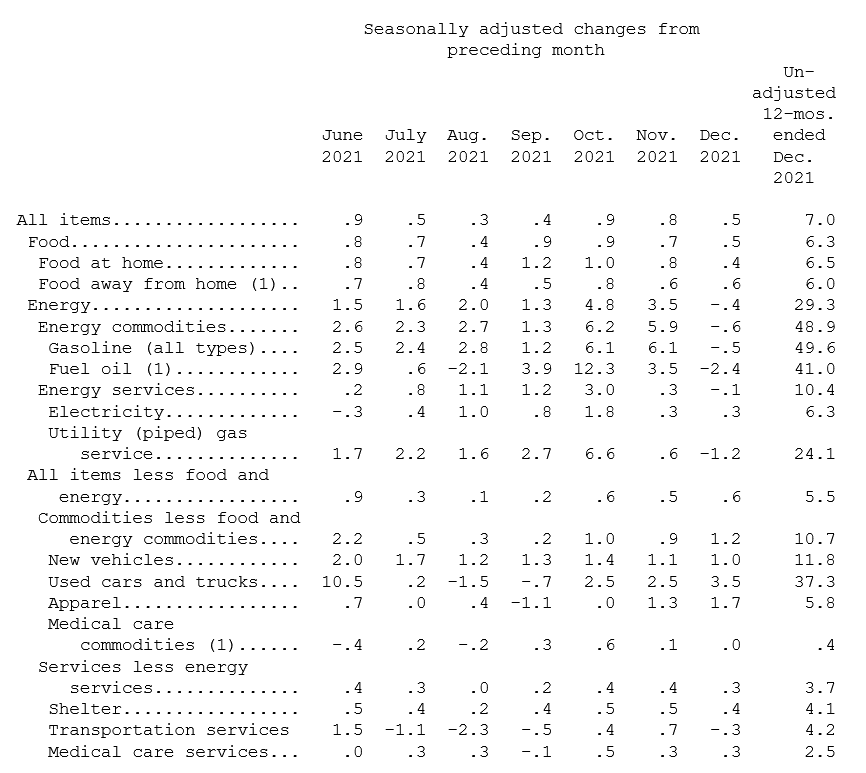

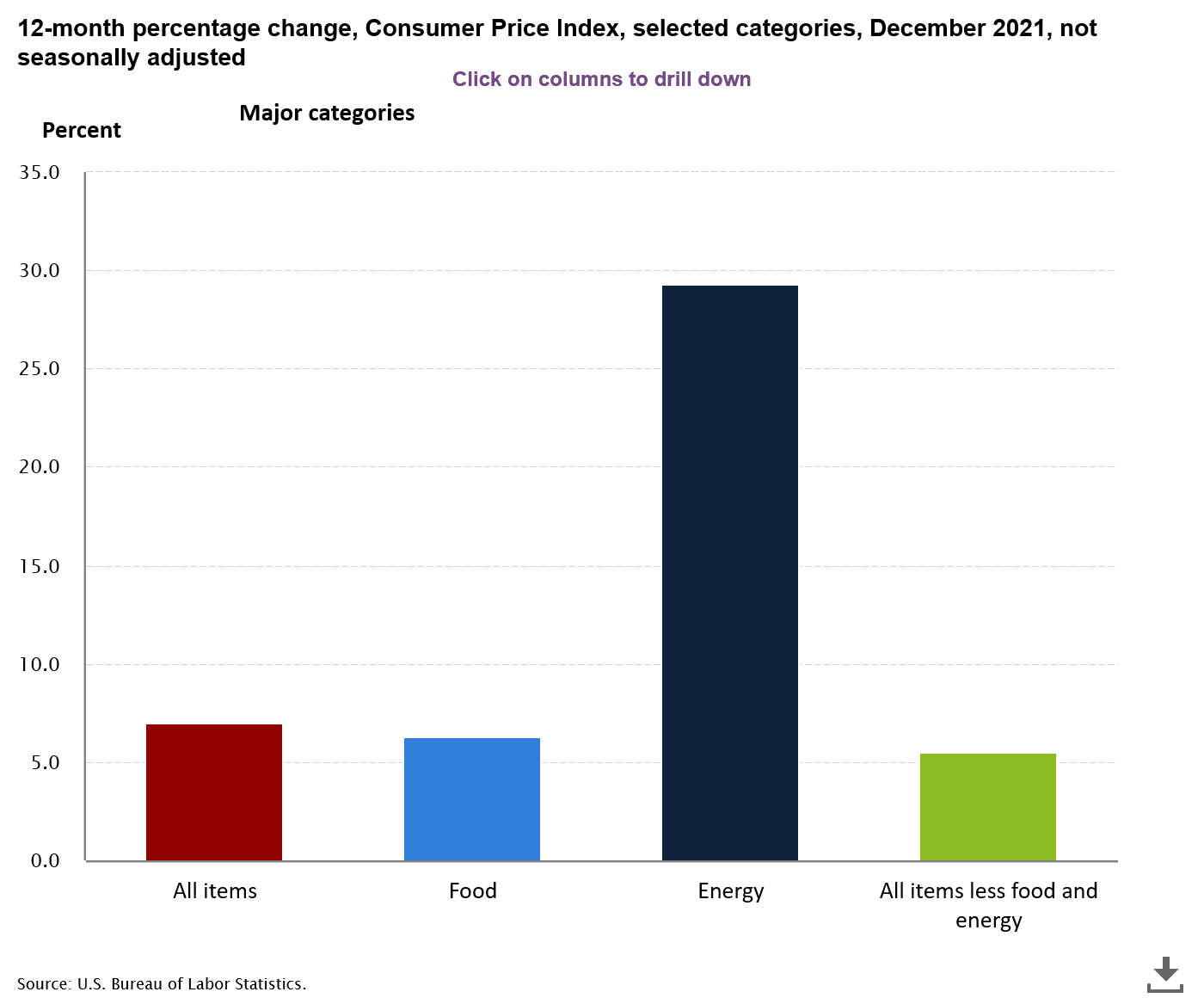

To appreciate the magnitude of the distortions present in the economy today, one merely needs look at the per-category breakdown of twelve-month price rises presented in yesterday’s CPI release.

While food prices “only” rose 6.3%, energy prices rose overall by 29.3%—and gasoline rose by 49.6%—during the past year. Shelter prices “only” rose 4.1%, but new vehicles rose 11.8% and used vehicles rose 37.3%.

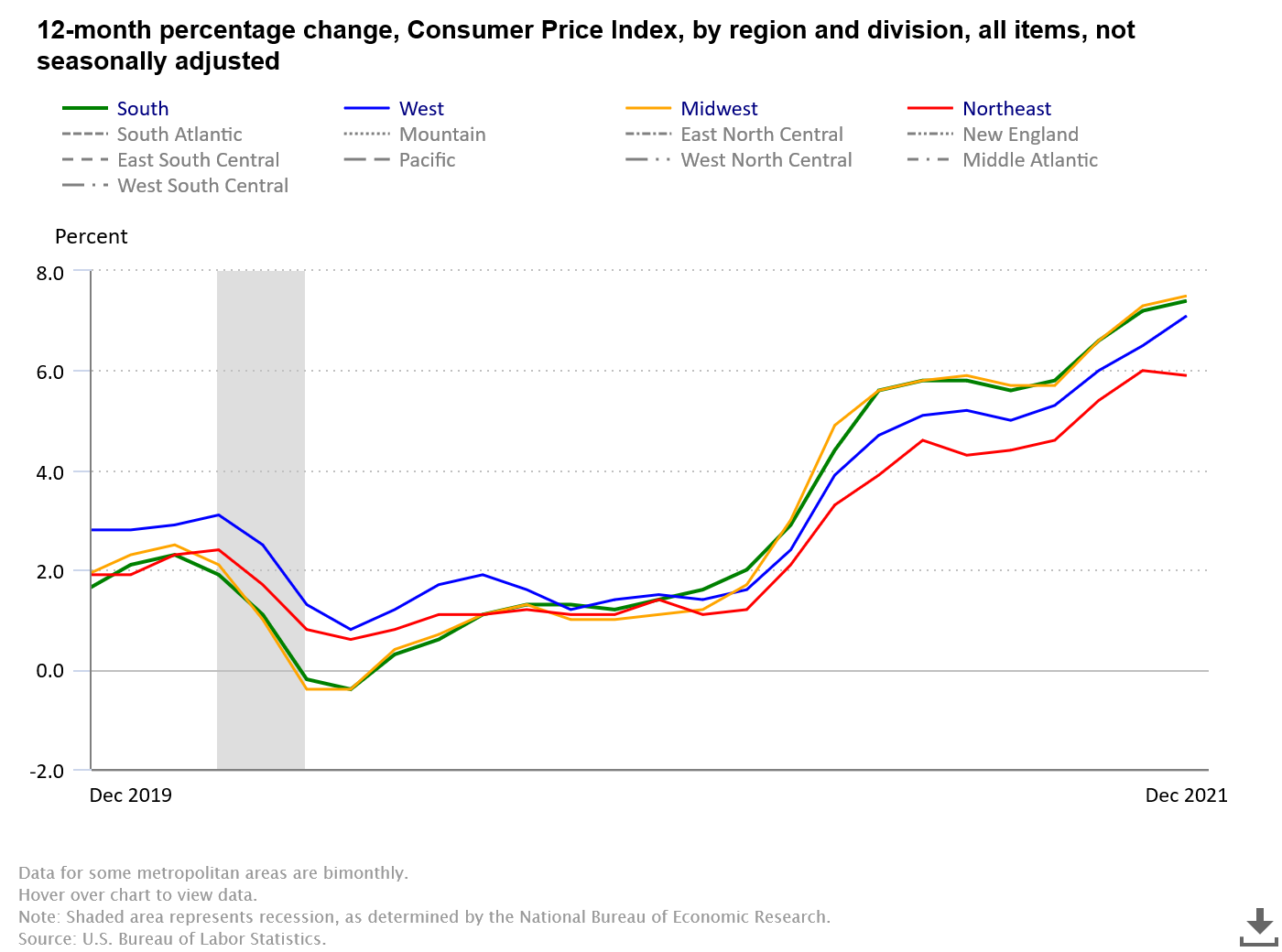

The magnitude of these variances can be seen in the BLS 12-month percentage change chart:

The Associated Press’ “explainer” on inflation attempts to spin price rises as indicative of a rebounding economy:

Much of the surge is actually a consequence of healthy economic trends. When the pandemic paralyzed the economy in the spring of 2020 and lockdowns kicked in, businesses closed or cut hours and consumers stayed home as a health precaution, employers slashed a breathtaking 22 million jobs. Economic output plunged at a record-shattering 31% annual rate in last year’s April-June quarter.

Everyone braced for more misery. Companies cut investment. Restocking was postponed. A brutal recession ensued.

But instead of sinking into a prolonged downturn, the economy staged an unexpectedly rousing recovery, fueled by vast infusions of government aid and emergency intervention by the Fed, which slashed interest rates, among other things. By spring this year, the rollout of vaccines had emboldened consumers to return to restaurants, bars, shops and airports.

Suddenly, businesses had to scramble to meet demand. They couldn’t hire fast enough to fill job openings — a near record 10.6 million in November — or buy enough supplies to meet customer orders. As business roared back, ports and freight yards couldn’t handle the traffic. Global supply chains became snarled.

The lockdowns did deliver quite a body blow to the economy, in the form of dual supply and demand shocks, as economic activity quite literally halted across much of the country. That supply chains are now snarled beyond description has been well documented by the media.

Yet the narrative that rebounding economic activity is the “root cause” of current price rises simply does not explain the extreme variances in the price shifts. Surging demand does not explain a 50% rise in the price of gasoline. Surging demand alone cannot explain a 37% rise in the prices of used vehicles, nor an 11% rise in the prices of new vehicles.

The release of “pent-up” demand might credibly explain some of the regional price rises that we are seeing, but the growing variances in price rises among various sections of the US merely adds a geographic dimension to the distortions the lockdowns have produced—some parts of the country are suffering more from the lockdown regime than others.

With some categories of consumer goods and services rising several times more than others, and with some parts of the country seeing greater price rises than elsewhere, even if the price rises are the result of increasing economic activity, such increases are demonstrably unequal, both geographically and by category. Unequal increases are distortions by definition.

Economic Growth?

For inflation to be the result of economic growth post-lockdown, there needs to be demonstrable economic growth. Has there been demonstrable economic growth?

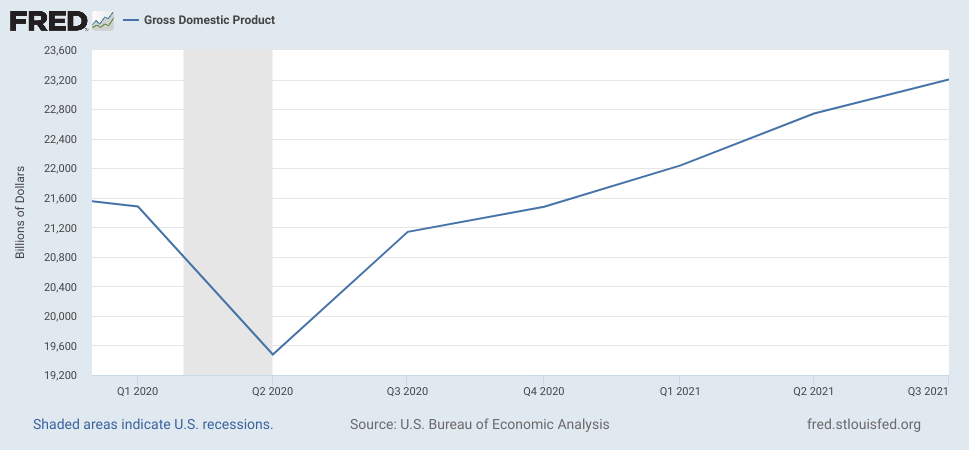

Looking at the country’s Gross Domestic Product, as estimated by the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank, the answer is uncertain. The nominal GDP measure has increased, although increases through July 2021 (the latest period for which data is currently available) do not reflect the levels of growth a tripling of average inflation would imply.

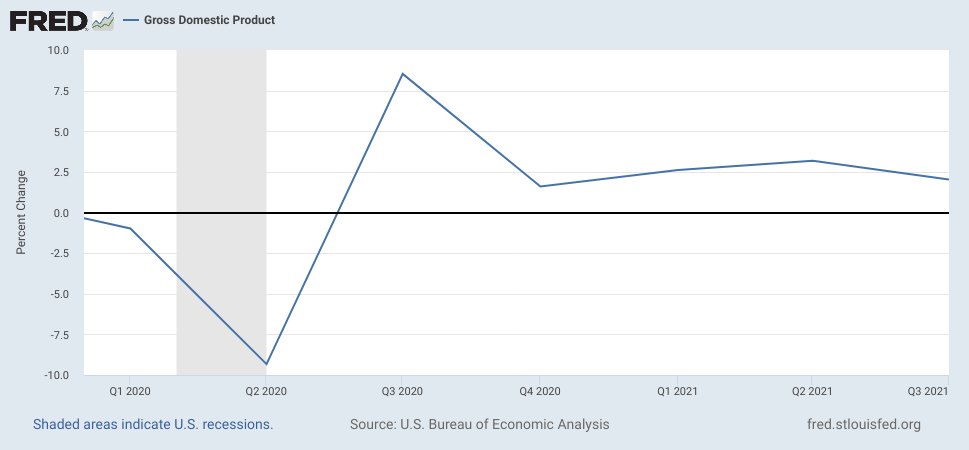

However, the percentage change shows the pace of economic expansion in the US to be slowing—the exact opposite of what would theoretically produce inflationary pressures and cause price rises.

Note that these metrics are for nominal GDP—meaning the effects of inflation are included. The pace at which inflation increased during 2021 suggests that, if the effects of inflation are removed from GDP metrics, what appears to be economic growth might actually be economic decline. At a minimum, the GDP data does not credibly show the torrid pace of growth that would result in a 7% annual rate of inflation.

Additionally, if economic growth is generating inflation, how is that inflation threatening economic growth, which Federal Reserve Chairman Jay Powell asserted in his recent Congressional testimony?

In his testimony, Powell rebuffed suggestions from some Democratic senators that rate increases would weaken hiring and potentially leave many people, particularly lower-income and Black Americans, without jobs. Fed rate increases usually boost borrowing costs on many consumer and business loans and have the effect of slowing the economy.

But Powell argued that rising inflation, if it persists, also poses a threat the Fed’s goal of getting nearly everyone wants a job back to work. Low-income families have been particularly hurt by the surge in inflation, which has wiped out the pay increases that many have received.

“High inflation is a severe threat to the achievement of maximum employment,” he said.

The economy, the Fed chair added, must grow for an extended period to put as many Americans back to work as possible. Controlling inflation before it becomes entrenched is necessary to keep the economy expanding, he said. If prices keep rising, the Fed could be forced to slam on the brakes much harder by sharply raising interest rates, threatening hiring and growth.

Citing inflation as a threat to economic growth stands at odds with pointing to inflation as proof of economic growth.

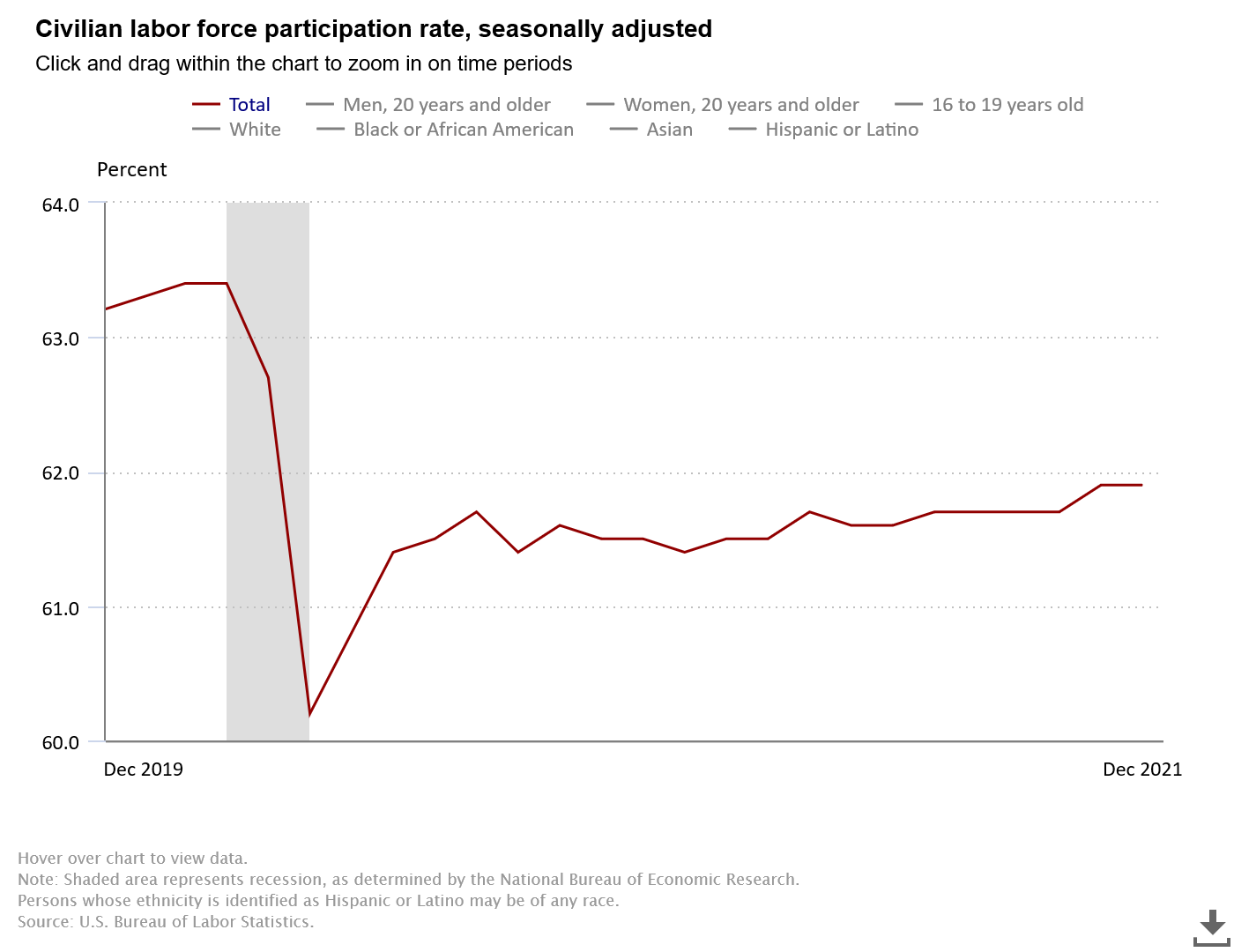

A quick review of the labor force participation rate confirms this perspective.

While a substantial portion of the workers pushed out of the labor force by the 2020 lockdowns and recession have been pulled back into the labor force, since April of 2020, the trend of labor force participation has been largely stagnant, hovering between 61.5% and 62%, whereas pre-pandemic it was at 63.4%

Some data from last Friday’s Employment Situation Report bears repeating here:

5.7 million individuals not currently listed as part of the labor force would like a job.

1.6 million of those individuals are considered “marginally attached” to the labor force, meaning they had looked for work in the past year but not in the past four weeks.

1.1 million individuals not in the labor force were prevented from looking for work due to various COVID quarantine and other protocols imposed by various levels of government.

An expanding economy would be creating the sort of employment pressures that would bring workers back off the sidelines and into the labor force. During 2021, those employment pressures simply were not in evidence.

If the economy is not expanding, it cannot be producing inflationary pressures—that is mathematically and logically impossible.

Distortion Is The Real Damage

The plain reading of the available data is that inflation is, by definition, economic damage inflicted by distortion of overall levels of both supply and demand.

Inflation due to a sudden scarcity of goods and services is not the result of an expanding economy, but a shrinking one.

Inflation that reduces real wages—as even Jay Powell has conceded is happening—is not inflation that is the result of people enjoying greater prosperity, as that would necessitate rising real wages.

Inflation that drastically alters relative prices among goods and services that every consumer requires—food, transportation, shelter, and energy—is inflation that is at every turn reducing the overall amount of these goods that can be acquired. Inflation means people are buying less yet paying more—which translates into a net reduction in economic output, not a net increase.

Yesterday’s inflation report paints a rather stark picture of an economy damaged and distorted by the pandemic lockdowns of 2020, and their inevitable economic fallout. Far from being the result of a rebounding economy, it is the result of an economy that is getting steadily worse, producing greater dislocations, and inflicting greater misery on the American consumer.

That is the legacy of the 2020 pandemic lockdowns and the continued heavy hand of pandemic-induced government regulation.