Today we have to consider something truly anomalous: interest rates are declining.

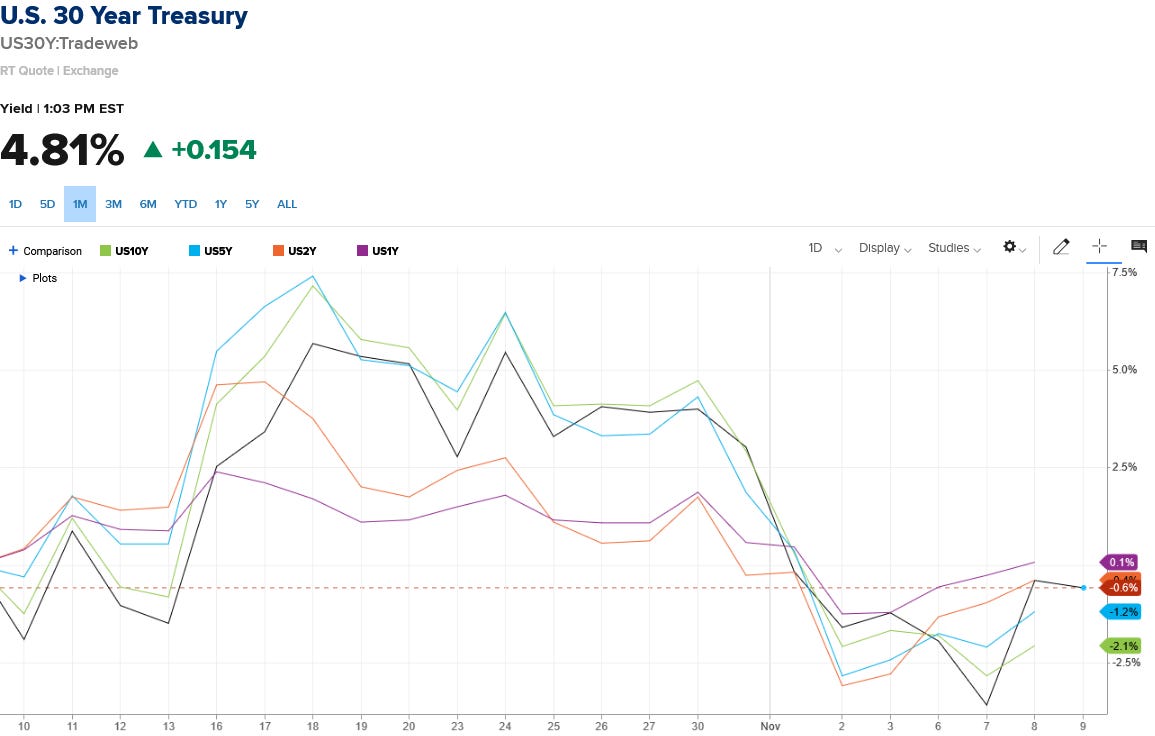

Over the past month, Treasury yields across the yield curve have fallen.

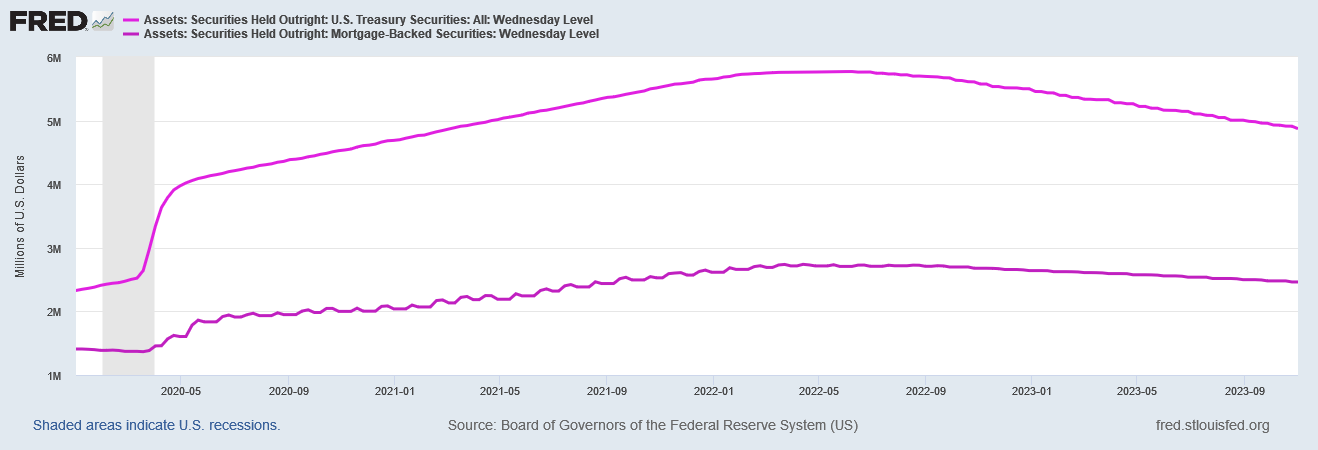

Readers will recall my earlier prognostications that interest rates are likely to rise over the near term as the Fed continues to shrink the money supply and reduce its balance sheet.

There are two consequences of this reduction of both the Fed balance sheet and the money supply which can produce upward pressure on interest rates.

First, with the Federal Reserve no longer being a net purchaser of Treasuries, aggregate market demand for Treasuries is declining. Declining demand leads to declining prices—and Treasury yields are the inverse of price, so that as they rise Treasury prices fall. Put another way, as Treasury prices fall, Treasury yields rise, and that is a good description of what is happening in the market.

Additionally, a reduction in the money supply is also a reduction in aggregate capital, meaning capital is more scarce for purposes of lending. Yields might be the inverse of securities prices with respect to purchasers of securities, but they are also the cost of capital to the issuers of such securities. When there is less capital available for borrowers to access the cost of that capital to borrowers must increase, and that again means higher interest rates.

Regardless of how one apprehends market interest rates, as the inverse of securities prices or the cost of capital, the end result is the same: the Fed’s balance sheet reductions are moving interest rates higher.

Over the past month, this projection has clearly not been the case, and for a more sustained period of time than mere market fluctuations can explain. Something larger is unfolding in financial markets, and we do well to consider what might be happening.

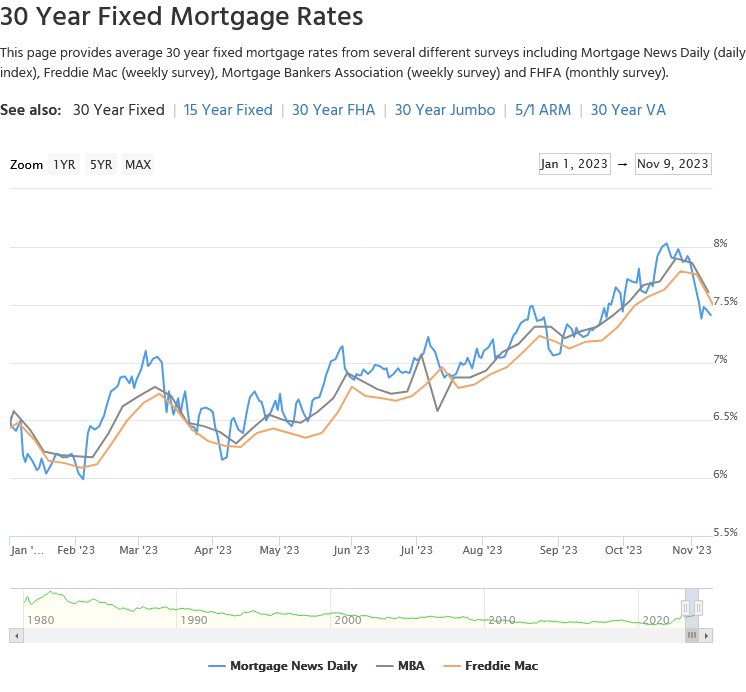

Perhaps the most notable interest rate decline has been the recent retreat of mortgage interest rates from the psychologically impactful 8% threshold.

The Great Pumpkin brought homebuyers a big present this Halloween: Mortgage rates’ biggest slide in a year.

The contract rate on the average 30-year fixed-rate mortgage declined 25 basis points last week to 7.61 percent, Bloomberg reported. That’s the lowest average mortgage rate recorded by the Mortgage Bankers Association since the end of September and a change from rates hovering around 8 percent.

Not only have mortgage rates receded, but within the past three weeks they have retreated approximately 50bps, from a momentary flirtation with 8% to hovering around 7.5% on a 30-year mortgage.

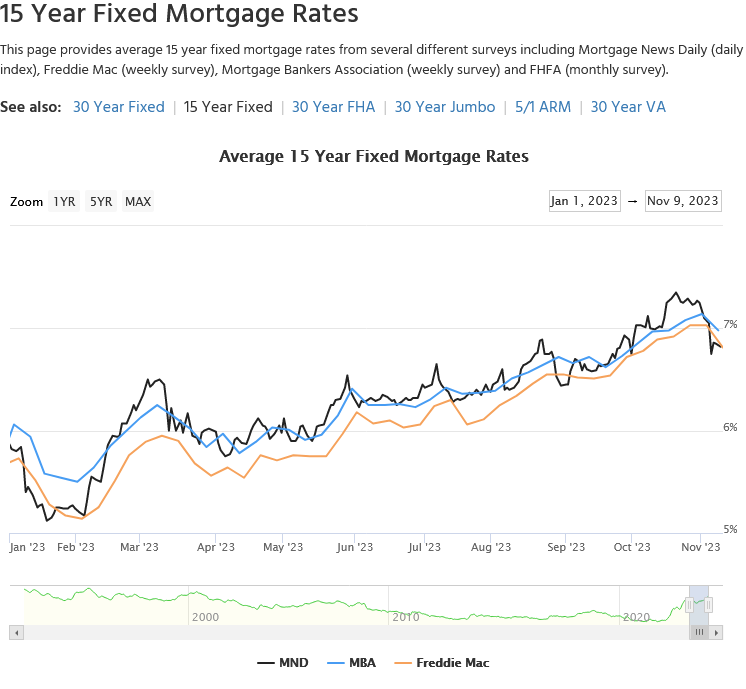

15-Year mortgage interest rates have posted similar declines since mid-October.

The proximate cause attributed by the corporate media for the decline in mortgage interest rates has been the decline in 10-Year Treasury yields.

While mortgage rates and the Federal Reserve’s interest rates aren’t directly correlated, the Fed’s decision last week to hold interest rates the same for the second straight monthly meeting may have done buyers a favor. The 10-year Treasury yield, which tracks more closely with mortgage rates, came down from its peak last week.

The spike in mortgage rates from pandemic lows pushed the housing market into a dry spell as buyers were sidelined by prohibitive purchasing costs. The MBA, National Association of Realtors and National Association of Home Builders made public appeals to Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell to stop with the rate hikes, citing concerns over how further damage to the market.

However, this assessment merely kicks the analytical can down the road. The Federal Reserve has not lowered the federal funds rate, nor has it ceased shrinking either its balance sheet or the money supply. Even if we accept the premise that mortgage rates are down because 10-Year Treasury yields are down, we still are left with the counterintuitive proposition that, with a shrinking Fed balance sheet and a shrinking money supply, Treasury yields are declining.

As a basic economic proposition, this does not happen—yet it is happening.

It is fairly certain that at least part of the decline in Treasury yields are yet another dosing of Wall Street’s favorite narrative drug, hopium. Since recession (really a deepening of the existing recession) is on deck, the Federal Reserve will presumably soon cut interest rates and pause the balance sheet run-off.

Guggenheim Investments thinks investors should look past the carnage in bonds and gear up for the Federal Reserve to pivot to rate cuts.

While the investment team expects the Fed to leave its policy rate unchanged at a 22-year high of 5.25% to 5.5% over the next several meetings, they also see a recession as likely in the first half of 2024.

That backdrop could spark a quick Fed pivot “to rate cuts, ultimately cutting rates by around 150 basis points next year and more in 2025,” said Matt Bush, U.S. economist at Guggenheim, in a client podcast published Monday.

“We have them taking the fed funds rate down a bit below 3% and pausing balance-sheet runoff in what we think will be a recession, albeit a mild one,” Bush said.

Some things will never change, and the inability of Wall Street to safeguard itself from policy reversals and even policy error is demonstrably one of those things. No matter what the economic fundamentals suggest is about to happen, Wall Street remains happily convinced the Federal Reserve will bail them out.

Consequently, Wall Street keeps dosing on debt instruments for their securities portfolios, believing that those portfolios will eventually appreciate in value.

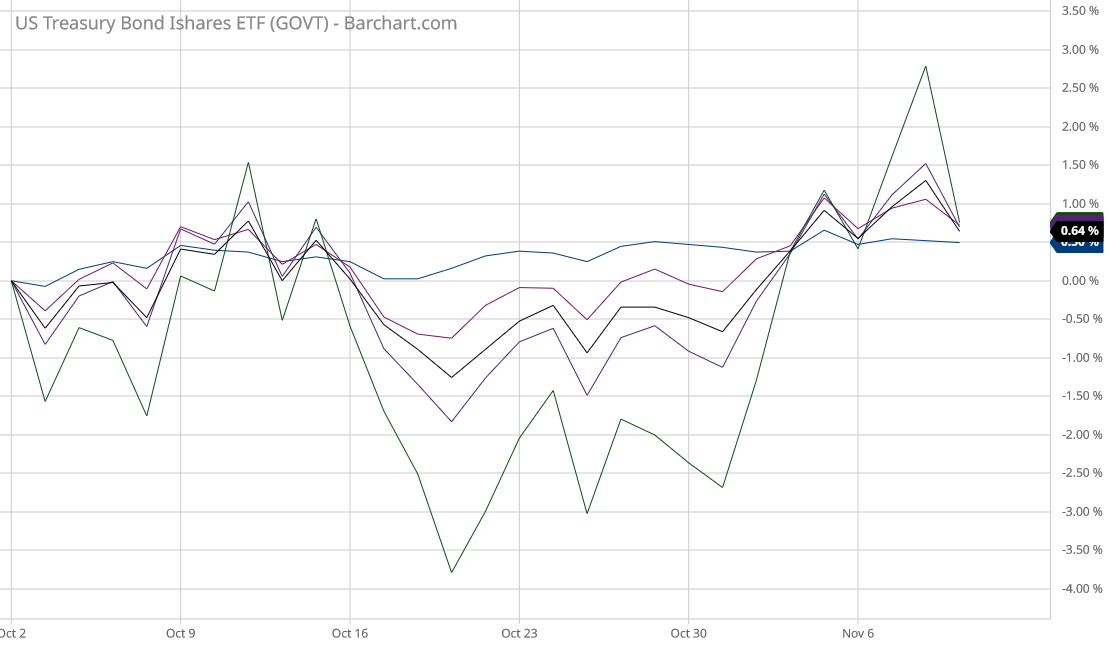

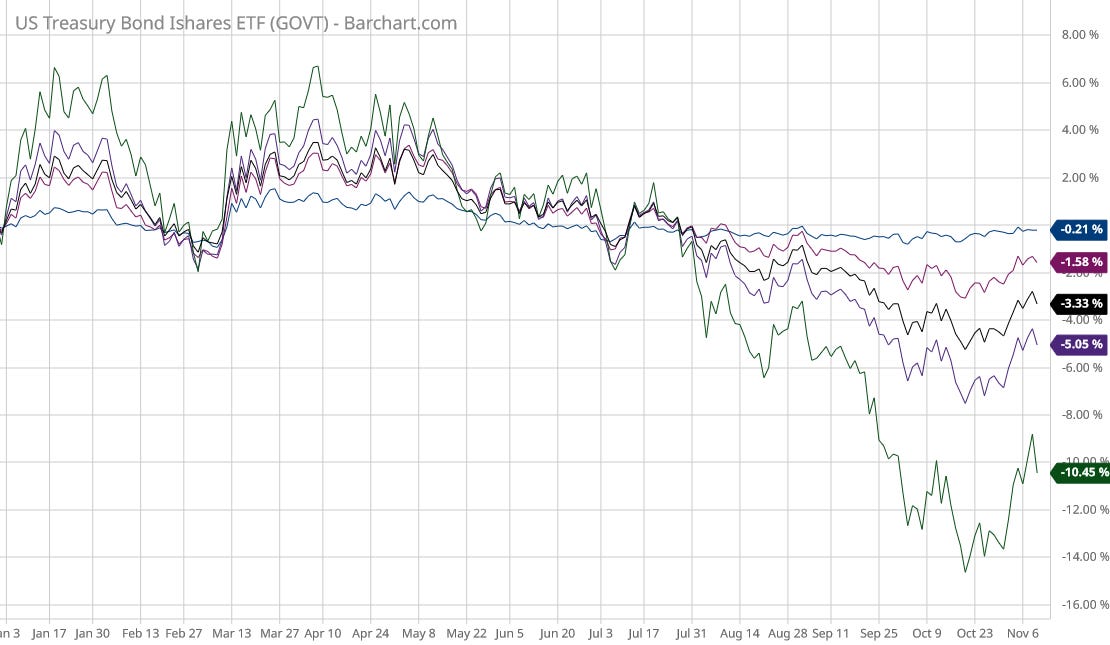

For now, Wall Street’s valuation of debt securities is at least not declining. Over the same period that interest rates have fallen, debt-related Exchange Traded Funds have largely held their own or slightly increased in value.

However, the current positive trend pales in comparison to even the year-to-date trend, which is largely down and down large.

Wall Street is unwise to conflate a stay of execution with a commutation of sentence. The markets have only postponed the valuation day of reckoning. There is as yet no good sign they have canceled it.

All of the factors I have previously cited as pushing interest rates up are still very much in play.

The Fed is still shrinking its balance sheet.

The money supply is still declining.

We should note, however, that there has been some amelioration in the pace of money supply shrinkage. Capital is still becoming more scarce but it is becoming more scarce more slowly than before.

Is Wall Street confusing that amelioration with outright easing of monetary policy? That is certainly one possibility.

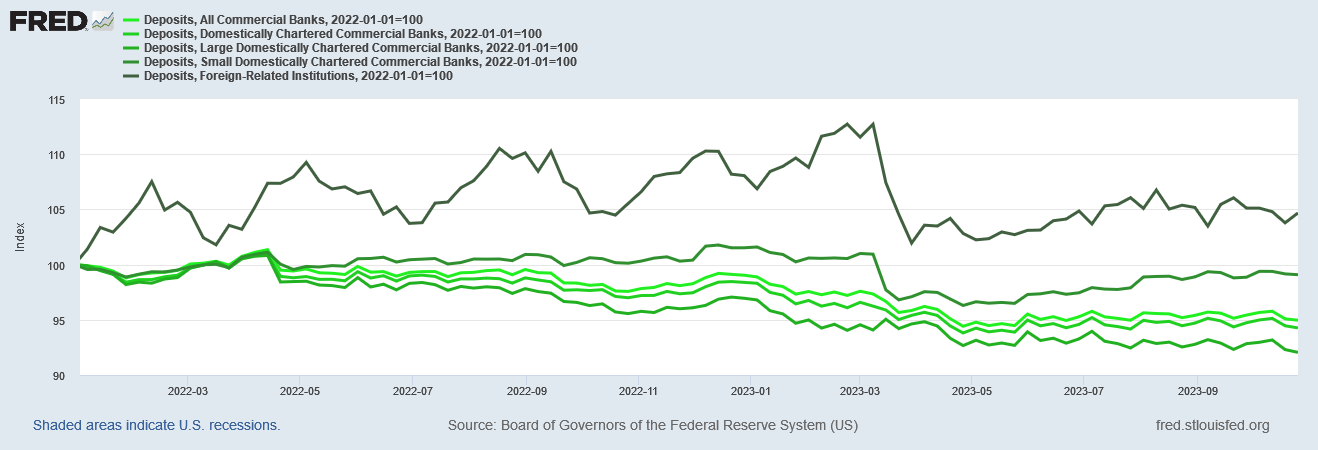

We must also note that, particularly among large banks, deposits are trending down again.

Small banks and foreign-related banks are still holding their own, but depositors are not giving large banks any vote of confidence.

A smaller Fed balance sheet means the Fed is not a net purchaser of securities, which is a decrease in demand for debt securities. Decrease in demand is a downward pressure on price, which for debt instruments is an upward pressure on yields.

Similarly, a smaller money supply means less capital available for lending, which makes the cost of capital more dear and is a direct upward pressure on yields.

Large banks losing deposits is a further constraint on their lending, which is again producing a scarcity of credit and thus represents an upward pressure on yields.

By these metrics, my earlier prognostication of higher interest rates is the logical extrapolation of the data, regardless of Wall Street’s perpetual delusions about being backstopped by the Fed.

So why are rates dropping?

From the borrower’s perspective, interest rates are going to rise when borrowers want to borrow and there’s less money to borrow. This is the classic relationship of supply and demand applied to capital markets.

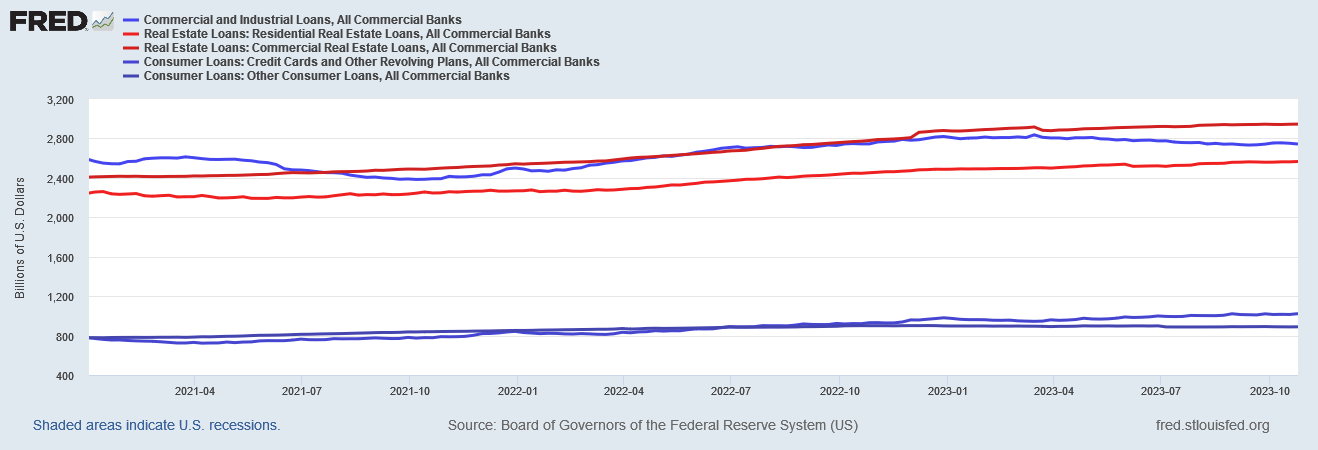

However, this also means the inverse is just as true: interest rates are going to decline when borrowers don’t want to borrow. When we look at various loan levels on bank balance sheets, we aren’t seeing a whole lot of borrowers wanting to borrow more.

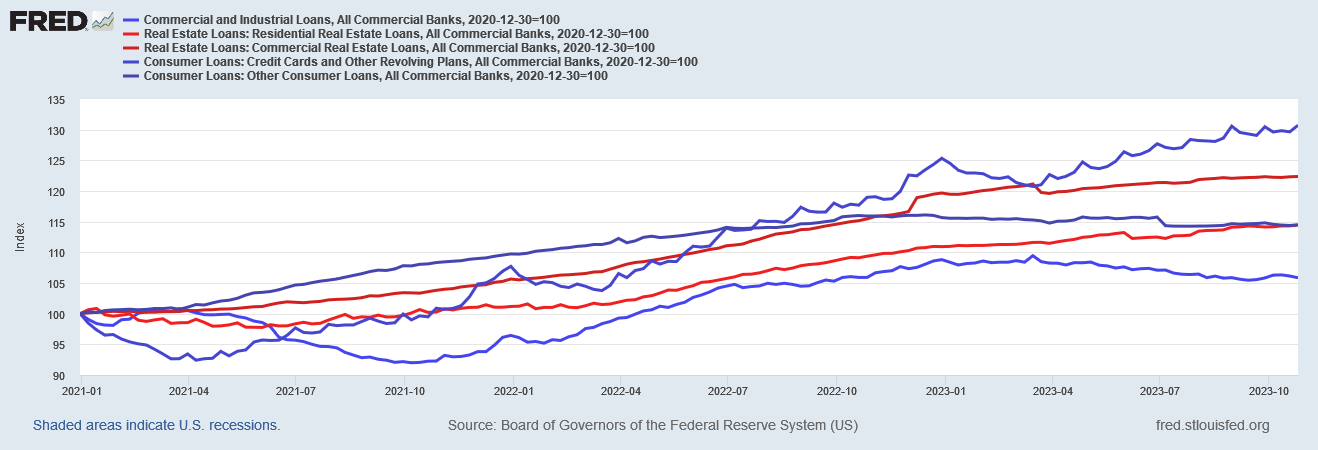

Real estate loans are still increasing, but slowly. Commercial loans, which are the other big tranche of bank loans, are on the decline.

If we index the loan categories to the end of 2020, we can see that consumer credit card and revolving loans are the only category posting significant growth percentages.

Real estate is in a holding pattern and other loans are declining.

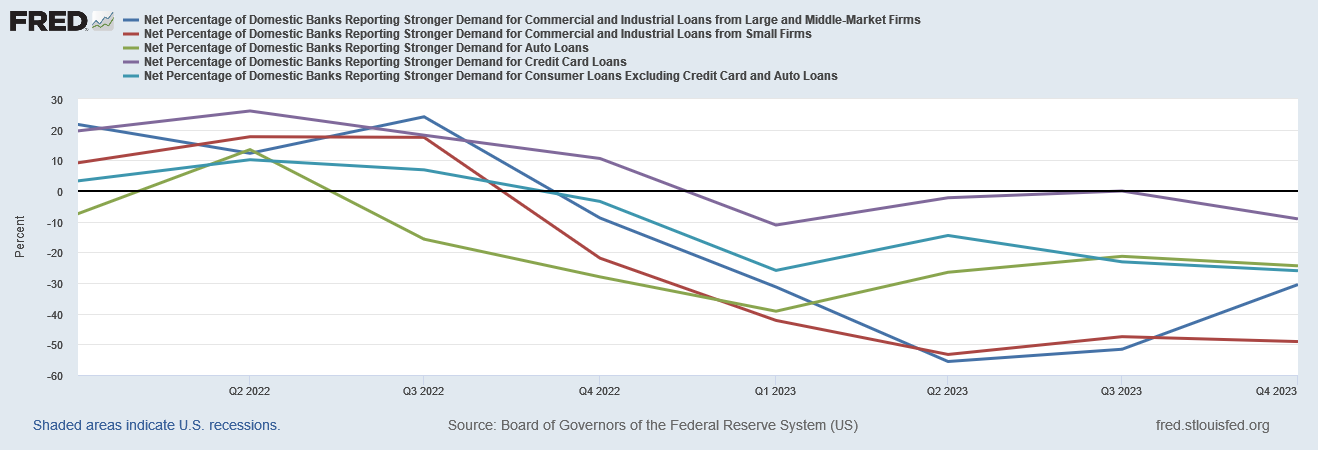

Nor is this merely an artifact of more stringent loan requirements and rising interest rates. Since the beginning of 2022, there has been a steady weakening of loan demand reported in loan officer surveys.

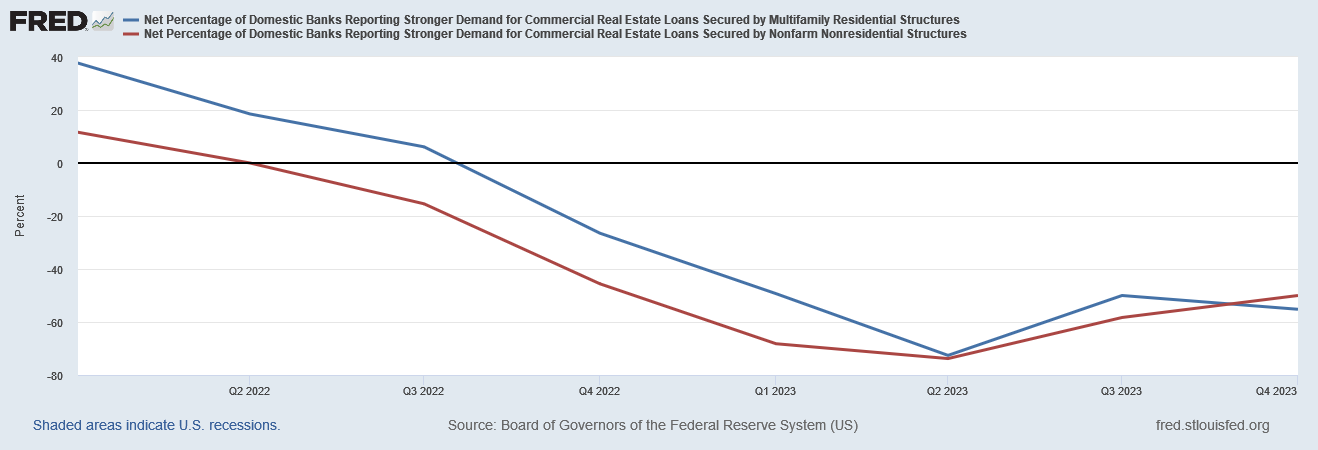

Commercial real estate loan demand has also dropped off.

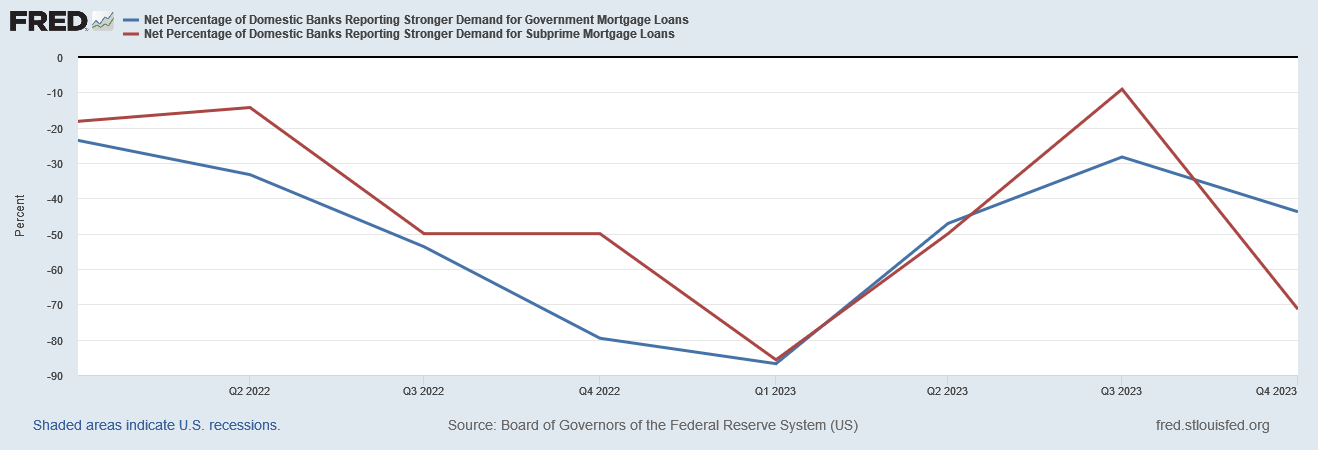

Even residential mortgage demand is shrinking.

While a declining capital base will push interest rates up, declining loan demand will pull interest rates down. At present, declining loan demand is expressing greater influence over market interest rates than the declining capital base.

This decline in loan demand is perhaps the surest sign that the US economy remains mired in a recessionary/stagflationary doldrums. At a fundamental level, loans, particularly loans for real estate and other capital assets (cars for individuals, equipment and machinery for businesses), represents investment in future economic potential, and in a bit of self-fulfilling prophecy can become that future economic potential.

Declining loan demand means individuals are not investing in their personal asset base, and companies are not investing in their business base. By definition this is a softening of aggregate demand particularly for physical goods which can play a part in wealth formation. Demand for services tends to take the form of a more immediate gratification and contributes less to wealth formation (which is why Adam Smith, in Wealth of Nations, described labor employed in manufacturing enterprises as “productive labor”1)

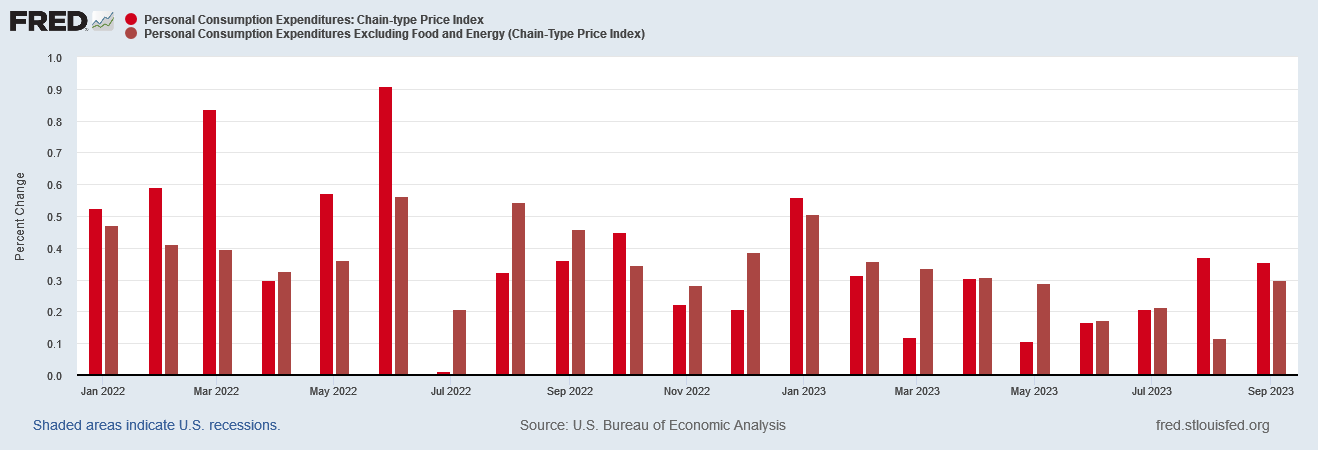

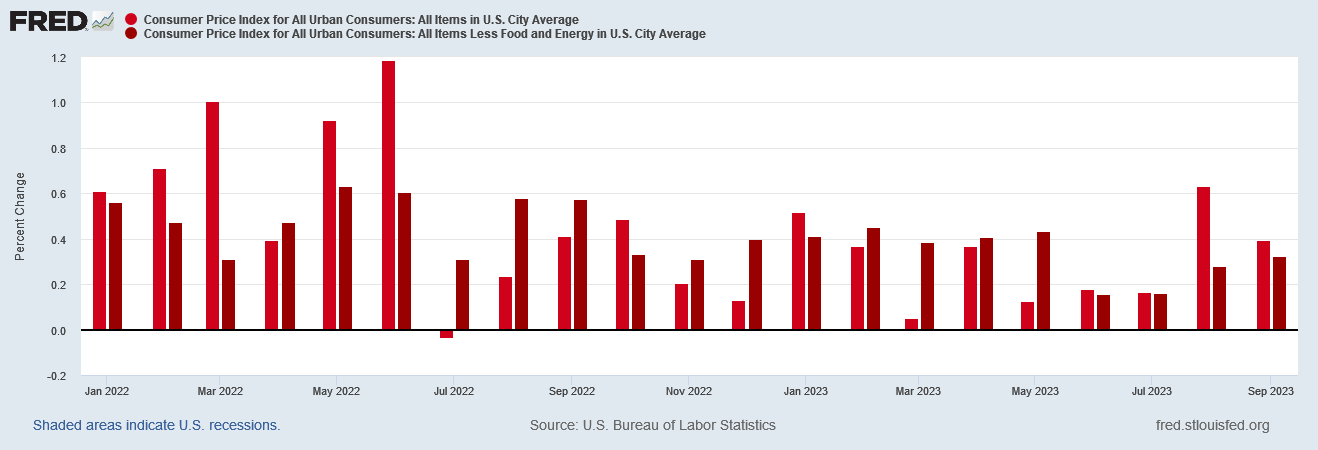

This softness in demand stands in stark contrast to the persistent upward price pressures that are slowly unraveling the Fed’s strategy for containing inflation, with core consumer price inflation per both the PCEPI and the CPI trending upward in recent months.

Softening demand plus persistent inflation is the epitome of stagflation, and that’s what is presenting in the US economy currently.

There has been confirmation of this in various inflation metrics, which show persistent rates of inflation even with goods prices falling outright and even most service prices increasing less slowly than before.

Even where inflation is not actually rising, it is continuing to distort relative price levels, which is contributing to the lack of aggregate demand, which in turn is diminishing loan demand, which at present is pulling interest rates down even as a shrinking capital base is exerting pressure to move interest rates up.

While Dementia Joe’s regime and other “experts” will tout the “strength” of the US economy and the success of the Federal Reserve in avoiding a recession, the reality of the US economy is that interest rates are trending down at the moment because the US economy is already in recession. Contrary to the bloviations of the “expert” class, what we are seeing in the US economy is weakness, not strength, and what is on deck is more weakness, not a return to strength.

Wall Street might look at falling interest rates with a measure of relief. Their cherished portfolios will not be losing value quite so quickly now, and for them that is good news.

Main Street will look at falling mortgage interest rates with relief, because it brings more housing into the price range of what the average consumer can afford.

However, more broadly, Main Street should look with concern at falling interest rates. That interest rates can be falling even as the money supply shrinks can only mean the economy is in much worse shape than anyone previously thought.

Smith, A. “Book II, Chapter III: Of the Accumulation of Capital, or of Productive and Unproductive Labour.” An Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, 1776, p. 136, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/38194/38194-h/38194-h.htm.

A cynic (and that would be me) would figure that Biden and his minions are touting the ‘strong economy’ because we’re coming into an election year, and they want to remain in power. But I’m left wondering just how much do THEY believe the economy is strong? Are you seeing anything in the data - maybe in footnotes, commentaries, quotations - that would indicate certain officials know full well that they’re ‘spinning’ the data to make the economy look better?