Since Israel and Iran have not decided yet whether their war should become WW3, I am going to take this opportunity to ponder whether or not the Federal Reserve should have trimmed the federal funds rate last month instead of punting yet again.

Spoiler alert: Yes, the Fed waited too long to cut the federal funds rate.

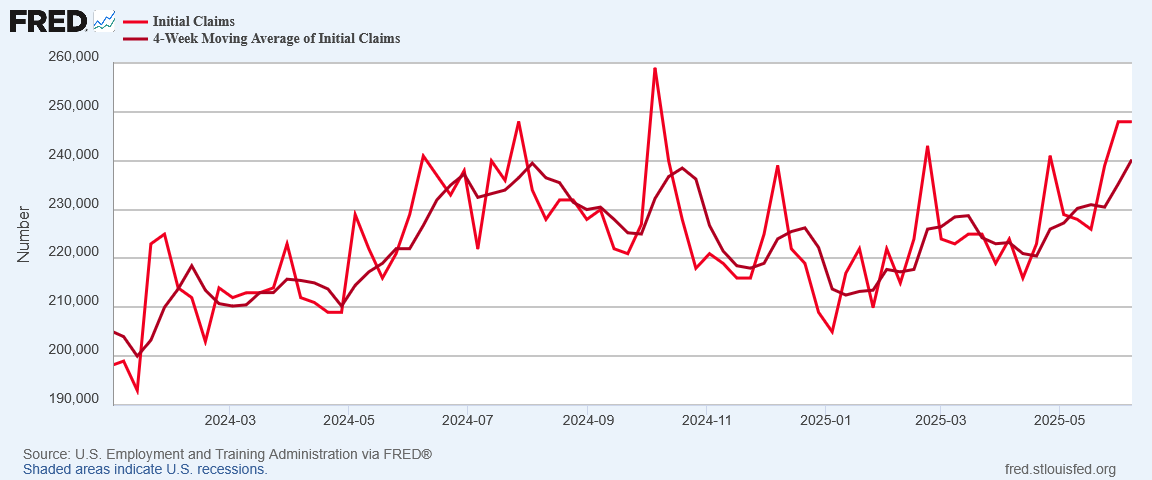

As I outlined yesterday, the Fed’s insistence on not doing anything and just standing there is increasingly challenged by rising joblessness in this country.

Yet it is not merely rising joblessness that builds the case for trimming the federal funds rate.

The Cleveland Fed’s inflation nowcast has been projecting disinflation and more disinflation since the start of the year.

Only when we look at the nowcast for the most recent month (June) do we see the projections coming in higher than before—and even that posits year on year inflation well below February. Between January and May the Cleveland Fed has projected lower consumer price inflation each month.

One reason the nowcast has until very recently trended down is the reality that import prices have not barely increased even after President Trump announced the Liberation Day tariffs.

Export prices, however, have risen somewhat, even after the announcement of the Liberation Day tariffs.

With exports commanding better prices and imports not showing any indication the Liberation Day tariffs have been at all impactful, as of this writing the one thing President Trump’s tariff and trade policies have not produced is consumer price inflation. Whether that is by accident or by design I cannot say, but that is the outcome that we are seeing at present.

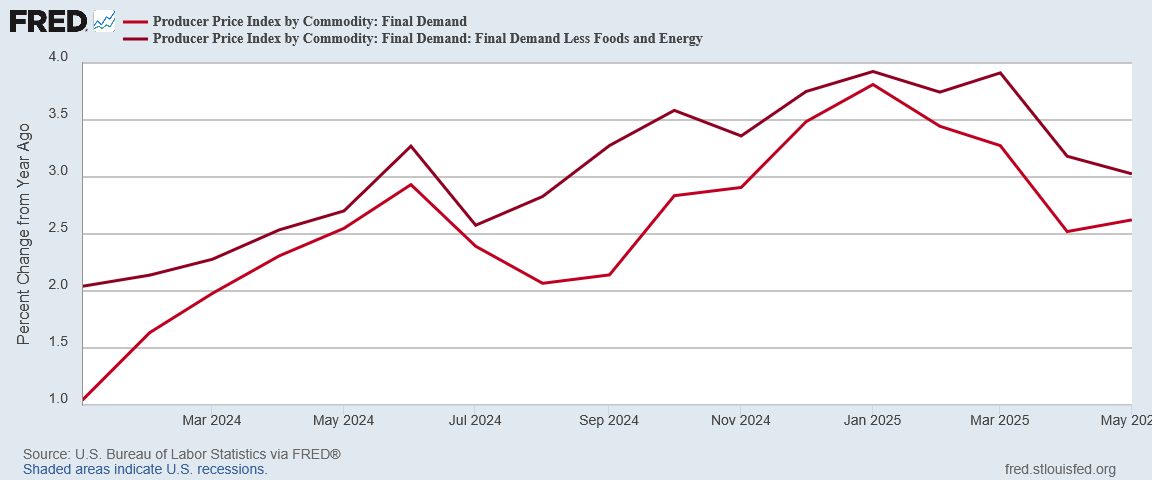

Additionally, the May Producer Price Index showed the disinflationary trend for factory gate prices was continuing. Since January the PPI has been trending steadily lower.

Remember, the PPI is a leading indicator for the CPI. A disinflationary trend within PPI generally prints as a disinflationary trend within the Consumer Price Index within a month or two. From a supply chain perspective, the prognosis for the next few months appears to be less inflation rather than more.

This disinflationary data comes on top of the latest jobs report, which showed once again that joblessness is on the rise in this country, a trend that has only been amplified by the unemployment claims data I mentioned the yesterday.

Initial claims are rising.

Continuing claims are as well.

As I argued when analyzing the May Employment Situation Summary, the jobs recession is still very much a stark reality for US labor markets.

With the macro data showing an extended disinflationary trend among consumer prices as well as a rising joblessness trend in employment, a workable case existed last month for a 25bps cut to the federal funds rate.

The Federal Reserve claims a dual mandate of price stability and facilitating full employment. A 25bps reduction in the federal funds rate last month would have been very much in line with both mandates.

Could the FOMC decide to play catch-up later today, making the rate cut today they should have made last month? They could, and we certainly cannot absolutely exclude the possibility.

However, between the uncertainties of war in the Middle East and the corresponding knock-on effect that war is having on oil and commodities prices, the signs of a potential return of inflation is likely to tap the breaks on any impulse among any of the FOMC members to defy expectations and cut the federal funds rate.

Since yesterday morning, oil prices have risen significantly, as the prospects for a ceasefire diminished.

Commodities prices have largely followed suit.

The war is opening the door from truly transitory consumer price inflation in response to rising energy and commodity prices. June and July at least are months where we should not be surprised to see prices trending somewhat higher.

Even though the war’s influence will not last long—most of the war-related price rises evaporated when the word began to spread that Iran wanted a ceasefire—that influence still exists. That influence is all that Powell needs to stand pat, especially with Wall Street already convinced he’s going to stand pat.

For now, the disinflation leg of the rate reduction argument has been significantly weakened.

Yet the Iran-Israeli War is not likely to last long—and not likely to last much longer.

That suggests the war’s impact on oil and commodities prices is also not likely to last much longer. The pronounced inflationary pressures we are seeing in oil and commodities are highly likely to ease by month’s end. In a best-case scenario, a successful conclusion to Israel’s attacks on Iran would lead to a resumption of the deflationary trend we have seen in energy prices overall since late 2022.

Meanwhile, unemployment claims will have trended still higher. The jobs recession will still have gotten that much worse.

The disinflation case and the jobs market case for a 25bps rate cut were there to be made last month. This month, the disinflation case is greatly diminished, while the jobs market case continues to grow stronger. The June case for rate cuts is weaker than the May case for rate cuts was.

In July, the disinflation case is likely to begin strengthening once more, but residual effects from Israel’s war with Iran may not have fully dissipated.

The jobs market case will have gotten even stronger still. Barring a dramatic shift in employment trends, the prognosis for jobs markets in this country is that joblessness is going to continue to rise.

The July case for a rate cut will likely be stronger than the June case, but it will still be weaker than the May case.

May was where the arguments within both the price mandate and the full employment mandate peaked in the short term.

With joblessness continuing to worsen in this country, the Fed’s full employment mandate obligates the Federal Reserve to implement policy changes that will facilitate job creation and further job growth. Within the Fed’s policy ambit, trimming the federal funds rate is a measure the Federal Reserve should be taking now, not later.

Jay Powell has been content to ignore the clear signals from US jobs markets as well as from the Fed’s own inflation projection tools, leaving rates higher than the jobs markets suggest they should be and doing nothing to move interest rates lower. Jay Powell has been content to not do his job.

By the time the Fed does get around to acting on interest rates, the employment picture in the US will likely have deteriorated to the point where a small 25bps rate cut may not have the needed impact, and a deeper 50bps+ will be needed. Jay Powell is kicking the interest rate can down the road, and ignoring how large that can is getting every time he does so.

What a smart analysis, Peter - you’ve thoughtfully integrated various factors in the most likely way. (Of course, the war scenarios are the wild cards.)

“…the prognosis for jobs markets in this country is that joblessness is going to continue to rise.” Peter, in coming months, analysts are going to be blaming rising joblessness on AI, and, of course, on the Orange Man Bad argument they think is applicable for everything that’s wrong in the world. What I’m hoping you can do, if the data allows, is separate rising joblessness into percentages caused by AI and by other causes. My guess is that it’s going to take a while for analysts to tease out the causes of rising joblessness, as the job market may change so fundamentally. I’ll bet that you will be among the first to see the patterns, and most accurately. I’m looking forward to reading your conclusions!