Aside from nearly being assassinated over the weekend, Donald Trump has had a good past few weeks. Still, the best news he’s received yet this month came when Federal District Judge Aileen Cannon dismissed Special Counsel Jack Smith’s classified documents case against him, on grounds that Smith’s Special Counsel appointment is unconstitutional.

In a 93-page ruling, District Judge Aileen Cannon said the appointment of special counsel Jack Smith violated the Constitution. She did not rule on whether Trump’s alleged mishandling of classified documents was proper or not.

“In the end, it seems the Executive’s growing comfort in appointing ‘regulatory’ special counsels in the more recent era has followed an ad hoc pattern with little judicial scrutiny,” Cannon wrote.

Unsurprisingly, Donald Trump celebrated the ruling with his usual Trumpian post on Truth Social:

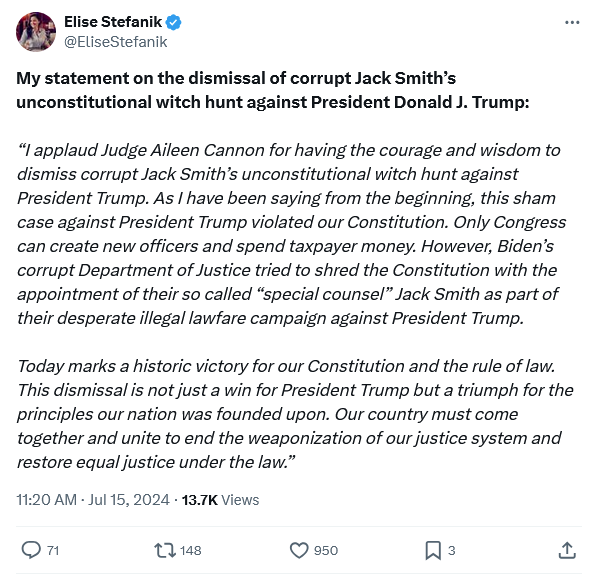

Also unsurprisingly, Trump’s supporters in Congress were similarly ecstatic.

Naturally, Trump’s adversaries within corporate media cried foul.

The ruling is obviously a win for Donald Trump. Is it a win for the rule of law? To determine that answer we have to dive into Cannon’s 93 pages of legal reasoning in United States v Trump1.

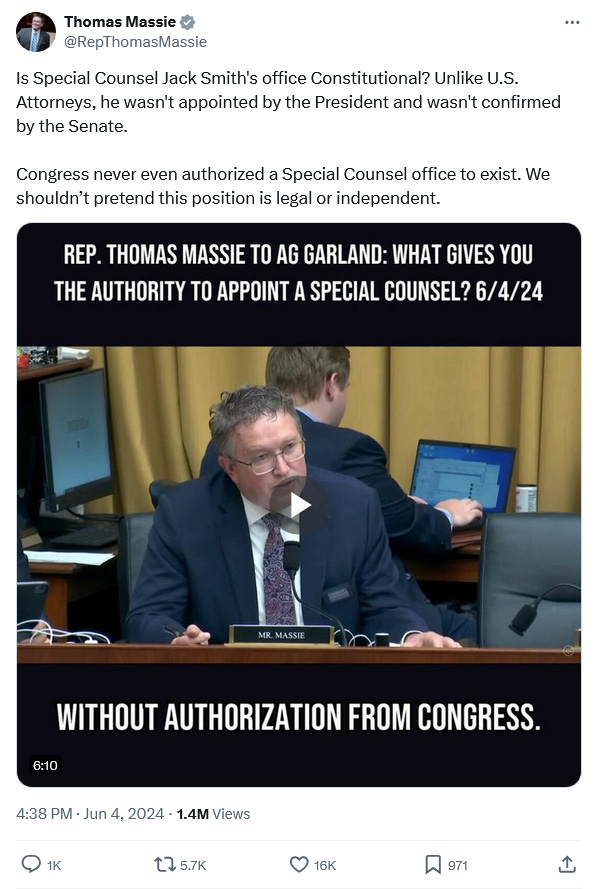

Perhaps the most important point to apprehend about Judge Cannon’s ruling is that it is not a radical departure from juridical reasoning. The constitutionality of Special Counsel appointments has been questioned before, and Congressman Thomas Massie, one of that body’s arch-libertarians, flatly rejects the premise.

The specific authority for appointing a special counsel is not explicitly mentioned in any federal statute, but rather in the federal regluations governing the Department of Justice—specifically, Title 28 on Judicial Administration, Part 600 Section 600.12.

The Attorney General, or in cases in which the Attorney General is recused, the Acting Attorney General, will appoint a Special Counsel when he or she determines that criminal investigation of a person or matter is warranted and—

(a) That investigation or prosecution of that person or matter by a United States Attorney's Office or litigating Division of the Department of Justice would present a conflict of interest for the Department or other extraordinary circumstances; and

(b) That under the circumstances, it would be in the public interest to appoint an outside Special Counsel to assume responsibility for the matter.

A Special Counsel’s jurisidiction is governed by Section 600.43.

(a) Original jurisdiction. The jurisdiction of a Special Counsel shall be established by the Attorney General. The Special Counsel will be provided with a specific factual statement of the matter to be investigated. The jurisdiction of a Special Counsel shall also include the authority to investigate and prosecute federal crimes committed in the course of, and with intent to interfere with, the Special Counsel's investigation, such as perjury, obstruction of justice, destruction of evidence, and intimidation of witnesses; and to conduct appeals arising out of the matter being investigated and/or prosecuted.

(b) Additional jurisdiction. If in the course of his or her investigation the Special Counsel concludes that additional jurisdiction beyond that specified in his or her original jurisdiction is necessary in order to fully investigate and resolve the matters assigned, or to investigate new matters that come to light in the course of his or her investigation, he or she shall consult with the Attorney General, who will determine whether to include the additional matters within the Special Counsel's jurisdiction or assign them elsewhere.

(c) Civil and administrative jurisdiction. If in the course of his or her investigation the Special Counsel determines that administrative remedies, civil sanctions or other governmental action outside the criminal justice system might be appropriate, he or she shall consult with the Attorney General with respect to the appropriate component to take any necessary action. A Special Counsel shall not have civil or administrative authority unless specifically granted such jurisdiction by the Attorney General.

This was the regulation upon which Merrick Garland relied when he appointed Jack Smith as Special Counsel. Therein lies the problem.

The creation of various offices within the Executve Branch of the federal government is regulated by the “Appointments Clause” within Article 2, Section 2, of the Constitution.

He shall have Power, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, to make Treaties, provided two thirds of the Senators present concur; and he shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, Judges of the supreme Court, and all other Officers of the United States, whose Appointments are not herein otherwise provided for, and which shall be established by Law: but the Congress may by Law vest the Appointment of such inferior Officers, as they think proper, in the President alone, in the Courts of Law, or in the Heads of Departments.

Two important points about the Appointments Clause: first, it mandates that all “principal officers” (Cabinet officials, US Attorneys, and similar positions) must be appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate; additionally, “inferior officers” are subject to the same appontment process except when Congress legislates otherwise.

Thus, the Constitutionality of Jack Smith’s appointment as Special Counsel hinges on two considerations: 1) Is he an “inferior officer” or a “principal officer”, and 2) has Congress vested his appointment in the Attorney General?

Judge Cannon ultimately declined to rule specifically on whether a Special Counsel is an inferior or principal officer within the context of the Appointments Clause, although she implies that the arguments are more compelling for Special Counsel being principal officers.

…the Court has proceeded under the premise, advanced by Special Counsel Smith, that he is an "inferior Officer," not a principal officer requiring Presidential nomination and Senatorial consent [ECF No. 405 pp. 6–12]. Defendants and the Meese amici contest this assertion, and it is a point worthy of consideration given the virtually unchecked power given to Special Counsel Smith under the Special Counsel Regulations. Ultimately, however, after examining the broad language in Supreme Court cases on the subject— and seeing a mixed picture, even if a compelling one in favor of a principal designation—the Court elects, with reservations, to reject the principal-officer submission and to leave the matter for review by higher courts.

She is able to punt on the principal officer designation because, regardless of designation, there is no law on the books empowering the Attorney General to appoint Special Counsel, despite the existence of Federal Regulations governing the practice. Indeed, other courts have previously acknoweldged this, most notably the DC Circuit Court of Appeals regarding the appointment of Iran-Contra Independent Counsel Lawrence Walsh4 (emphasis mine):

We have no difficulty concluding that the Attorney General possessed the statutory authority to create the Office of Independent Counsel: Iran/Contra and to convey to it the "investigative and prosecutorial functions and powers" described in 28 C.F.R. Sec. 600.1(a) of the regulation. The statutory provisions relied upon by the Attorney General in promulgating the regulation are 5 U.S.C. § 301 and 28 U.S.C. §§ 509, 510, and 515. While these provisions do not explicitly authorize the Attorney General to create an Office of Independent Counsel virtually free of ongoing supervision, we read them as accommodating the delegation at issue here.

This admission is important because 28 USC §§5095, 5106, and 5157 are specifically cited by Jack Smith as the statutory authority governing his appointment. Simply put, the DC Circuit Court of Appeals has already conceded there is no such statutory authority. Indeed, in that Iran-Contra ruling, the DC Circuit Court acknowledged in a footnote that the authority was merely “presupposed”.

In U.S. v. Nixon, 418 U.S. 683, 694-96, 94 S. Ct. 3090, 3100-01, 41 L. Ed. 2d 1039 (1974), the Supreme Court presupposed the validity of a regulation appointing the Special Prosecutor, a position indistinguishable from the one at issue here

In other words, the courts have simply assumed Special Counsel were valid, without ever actually interrogating the Constitution on the matter.

Moreover, this lack of explicit statutory authority was conceded again by the DC District Courts during Robert Mueller’s tenure as a Special Counsel8, citing the same Iran-Contra ruling by the DC Circuit.

It is also noteworthy that the DC District Court also largely agrees with Judge Cannon’s analysis on principal vs inferior officer status for Special Counsel, concluding that a Special Counsel is an “inferior officer” subject to appointment by the Attorney General solely because the Attorney General can simply void the governing regulations if the Special Counsel becomes a problem.

In the absence of procedural requirements or judicial review to hamstring his discretion, the Acting Attorney General retains the power to rescind or revise the Special Counsel regulations at will, and any purported limits on the power to remove or countermand persist only with the acquiescence of the Acting Attorney General. As a result, the Special Counsel is effectively removable at will, subject to the Acting Attorney General’s plenary supervision, and thus an inferior officer.

Essentially, the DC District Court held that, because the Attorney General can always just rewrite Title 28 Part 600 of the Code of Federal Regulations, he has ultimate control over Special Counsel, making the Special Counsel an inferior officer within the context of the Appointments Clause, and the courts merely assume that Congress has somewhere somehow with some unknown bit of legislation delegated the appointment authority to the Attorney General.

If that legal reasoning seems adequate to you, then you probably agree with the appontment of Special Counsel. If that legal reasoning seems convoluted and contorted nonsense to you, you probably don’t. I will give the reader one guess which view is mine!

Suffice it to say, Judge Cannon rejects the logic of the DC Circuit, and the logic advanced by Jack Smith in defense of his office.

Curiously, Judge Cannon stops short of a sweeping declaration that 28 CFR §600.1 et seq is completely unconstitutional. She confines the scope of her reasoning to Jack Smith’s appointment.

That may serve to disappoint the naysayers in the corporate media who argue that Judge Cannon’s ruling similarly invalidates the appointment of US Attorney David Weiss as Special Counsel over Hunter Biden’s numerous legal troubles.

Speaking about the matter on MSNBC, [Andrew] Weissmann explained that Cannon is restricting the executive branch's power, and it isn't within her scope as a Florida district judge to do something like that.

"I'm sure a lot of viewers are going, but what are you talking about? Special counsel Mueller was a special counsel, and that was upheld. Special counsel Rob Hur, who investigated the current sitting president, Joe Biden. He was able to do that. There is a current special counsel who has prosecuted Hunter Biden and is still prosecuting Hunter Biden," said Weissmann.

A key point to be made about Weissman’s derogation of a Federal District Court judge’s authority: it is absolutely within the scope of any Federal District Court judge to restrict the executive branch’s power by requiring the executive branch to adhere to the strictures of the US Constitution. That is part and parcel of the entirety of the Federal court system’s authority, at all levels.

Further, as legal scholar Jonathan Turley noted at the time of David Weiss’ appointment of Special Counsel, Attorney General Merrick Garland disregarded the requirements of 28 CFR §600.39 that Special Counsel be from outside the Justice Department—David Weiss was the US Attorney investigating Hunter Biden. Thus, Weiss’ appointment is already open to Constitutional and procedural challenge, prior court rulings to the contrary notwithstanding.

Indeed, the Hunter Biden case may merely amplify the structural defects in the Department of Justice’ current practice of appointing Special Counsel, much as the text of various rulings on Robert Mueller’s appointment arguably does, and indeed as the Iran-Contra rulings so often cited in Special Counsel cases arguably does.

Given the structurally bizarre and legally perverse construction of Jack Smith’s cases against Donald Trump, such defective appointments can easily be seen as part of the Federal Government’s “lawfare” strategy to hamstring Donald Trump as a political opponent for Joe Biden.

Given the defective legal theories Jack Smith deployed to make his cases against Donald Trump—theories which have now been rejected by the Supreme Court—it is past time we reconsider the premise that Jack Smith is in any way a duly appointed officer of the courts.

Not for nothing did the House Judiciary Committee issue its scathing denunciation of that strategy as it was deployed in Alvin Bragg’s “hush money” case.

It comes as no surprise that Jack Smith intends to appeal Cannon’s ruling.

In a statement Monday evening, Peter Carr, spokesman for the special counsel’s office, said that the Justice Department has approved plans to appeal.

“The dismissal of the case deviates from the uniform conclusion of all previous courts to have considered the issue that the Attorney General is statutorily authorized to appoint a Special Counsel,” Carr said. “The Justice Department has authorized the Special Counsel to appeal the court’s order.”

Ultimately, he has little choice. Even if he is willing to concede the classified documents case, the legal reality is that his appointment as Special Counsel is the same appointment in both that case and the J6 case against Donald Trump.

If Smith’s appointment as Special Counsel is unconstitutional as regards the classified documents case, it absolutely must be unconstitutional in whatever remains of the J6 case.

However, Jack Smith’s office is ignoring a key point: the courts have never actually considered the substance of the Attorney General’s statutory authority to appoint Special Counsel, choosing instead to merely assume the authority exists—even as they acknowledge the statutes most commonly cited to justify Special Counsel appointments do not explicitly provide that authority.

Yet statutory authority is discrete and specific, not vague and nebulous. If Congress has given the Attorney General statutory authority to appoint Special Counsel, there is a specific statute that expressly provides that authority. If there is no specific statute, there can be no statutory authority. The common citations of precedent rationalizing the legitimacy of Special Counsel appointments do not make reference to a specific statute, and at best “presuppose” the authority.

It is conceivable the Supreme Court will overturn Cannon’s ruling and reinstate the documents case against Donald Trump. I do not presume to have any insight how the Court will ultimately rule on the matter. I am certain that this case will be very quickly before the Supreme Court, if only because Cannon has spoken the quiet part out loud, and only the Supreme Court can now put the matter finally to rest one way or the other.

Yet even so, this is still a major setback for the lawfare strategy that has been arrayed against Donald Trump. There are no more sessions scheduled in the Court’s 2023-2024 term, which makes it unlikely the Court will hear any appeal before October at the earliest, making a ruling before the November election very near an impossibility. With the J6 case effectively at a standstill while the courts sort through what parts of the case do and do not fall under Executive Immunity, and the sentencing in the now-completed “hush money” case similarly stalled, the classified documents case was the only portion of the array of court cases not completely stymied.

The singular defect of lawfare has always been its willingness to run roughshod over not just due process, but judicial process. There is a right way for government to prosecute even Presidents for their misdeeds. That way is not always quick and rarely is it easy, but the mechanisms of accountability have always existed, both in impeachment and the possibility of indictment after an impeachment conviction.

Jack Smith did not want to do things the right way. The Democrats in government did not want to do things the right way.

Cannon’s ruling is ultimately the correct one. Because Smith refused to do things the right way, he does not get to have his way at all. Within the court system, that’s what justice looks like—doing things the right way.

United States District Court, Southern District of Florida, West Palm Beach Division, United States of America v Donald J. Trump, Waltine Nauta, and Carlos De Oliveira. DocumentCloud, 2024

In Re Sealed Case, 829 F.2d 50 (D.C. Cir. 1987)

United States v. Concord Mgmt. & Consulting LLC, 317 F. Supp. 3d 598 (D.D.C. 2018)

I've read some of the opinion. Clarence Thomas in his concurrence of the POTUS immunity posited likewise. US v Maurice was a precedent as Justice Thomas pointed out. That being said, is it not the Democrats own error that when they controlled the House they did not construct an enabling statute for the Special Counsel? And will the next Congress correct that mistake and construct such a statute for successive administrations?

“If Smith’s appointment as Special Counsel is unconstitutional as regards the classified documents case, it absolutely must be unconstitutional in whatever remains of the J6 case.”

When the Supreme Court issues it’s ruling, is it likely that they will make a ruling that affects the J6? That is, a broad rather than specific ruling?

I’m still hoping for our legal system to right a grave wrong.

I remain in awe of your exceptionally great legal mind, Peter!