The biggest COVID headline today is Merck’s announcement that it is seeking FDA approval (emergency use authorization) for its antiviral therapeutic molnupiravir, after clinical trial results showed the medication is as an highly effective treatment for COVID-19, the disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Merck & Co Inc's (MRK.N) experimental oral drug for COVID-19, molnupiravir, reduced by around 50% the chance of hospitalization or death for patients at risk of severe disease, according to interim clinical trial results announced on Friday.

Merck and partner Ridgeback Biotherapeutics plan to seek U.S. emergency use authorization for the pill as soon as possible, and to submit applications to regulatory agencies worldwide. Due to the positive results, the Phase 3 trial is being stopped early at the recommendation of outside monitors.

"This is going to change the dialogue around how to manage COVID-19," Robert Davis, Merck's chief executive officer, told Reuters.

This comes on the heels of Pfizer commencing what could be the final study of its antiviral medication against COVID-19.

The mid-to-late-stage study will test Pfizer's drug, PF-07321332, in up to 2,660 healthy adult participants aged 18 and older who live in the same household as an individual with a confirmed symptomatic COVID-19 infection.

In the trial, PF-07321332, designed to block the activity of a key enzyme needed for the coronavirus to multiply, will be administered along with a low dose of ritonavir, an older medication widely used in combination treatments for HIV infection.

If these drugs receive emergency use authorization (and, ultimately, full FDA approval), they do indeed point to a change in the “dialogue around how to manage COVID-19”. However, the change is not perhaps the one either Merck or Pfizer intended. Their research efforts highlight an important point that has been largely overlooked in the media narratives surrounding COVID-19: the use of therapeutic drugs to treat the disease.

If the Merck and Pfizer research efforts are productive (and the data certainly suggests that they are), then the possibility of therapeutic rather than immunization approaches to the SARS-CoV-2 virus must be accepted as valid—and that invites a reconsideration of the drugs Ivermectin and Hydroxychloroquine, both of which have long enjoyed full FDA approval (although not specifically for COVID-19) and are already widely available.

Does Ivermectin Work?

The media narratives surrounding Ivermectin have been uniformly perjorative: Ivermectin is not a treatment for COVID-19 and should not ever be taken for COVID-19:

The idyllic photo of a chestnut horse appeared on the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s Instagram feed in August, along with a blunt caption: “You are not a horse. Stop it with the #Ivermectin. It’s not authorized for treating #COVID.”

The post was one of several stark warnings issued about ivermectin — an anti-parasitic medication being promoted by prominent conservative media figures and politicians, as well as some physicians, as an effective treatment for covid-19, despite the lack of scientific evidence showing there are benefits of taking the drug for that purpose.

There is a certain irony in the FDA posting on Instagram that Ivermectin is for horses, not humans, for even the CDC acknowledges that Ivermectin is an FDA-approved medication (approved for humans, as well as horses).

Ivermectin is a U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved prescription medication used to treat certain infections caused by internal and external parasites. When used as prescribed for approved indications, it is generally safe and well tolerated.

While it is fair to question the efficacy of the drug against COVID-19, for the FDA to seem ignorant of its own approval of the drug as being safe for humans is more than a little disingenuous, and arguably dishonest.

What is unquestionably dishonest—or at the very least incompetently inaccurate—is the Washington Post’s assertion of a lack of scientific evidence of Ivermectin’s efficacy for treating COVID-19. There are, as of September 29, 2021, no fewer than 65 separate studies on Ivermectin as a COVID-19 therapeutic, and the majority of those studies do indeed demonstrate significant efficacy against the disease.

•Meta analysis using the most serious outcome reported shows 66% [53‑76%] and 86% [75‑92%] improvement for early treatment and prophylaxis, with similar results after exclusion based sensitivity analysis and restriction to peer-reviewed studies or Randomized Controlled Trials.

•Statistically significant improvements are seen for mortality, ventilation, ICU admission, hospitalization, recovery, cases, and viral clearance. 30 studies show statistically significant improvements in isolation.

•Results are very robust — in worst case exclusion sensitivity analysis 54 of 65 studies must be excluded to avoid finding statistically significant efficacy.

When one examines just the Randomized Controlled Trials of Ivermectin (32 to date), the drug demonstrates a 63% improvement in patient outcomes when used for early treatment, a 30% improvement in patient outcomes when used as a late treatment, and an 84% improvement in patient outcomes when used as prophylaxis.

The 45 Peer-Reviewed studies show 70% improvement in the early treatment cohort, 43% improvement in the late treatment cohort, and 86% improvement in the prophylaxis cohort.

To be sure, not all the studies show positive outcomes for Ivermectin. 3 peer-reviewed studies had results favoring the control for early treatment and 2 favored the control for late treatment.

Still, the most important consideration for evaluating any scientific presentation of evidence is reproducibility. One study is not the be-all, end-all of scientific inquiry, and the most reliable presentations of evidence are invariably the ones which are capable of being replicated by independent teams of researchers. When 40 out of 45 peer-reviewed studies demonstrate efficacy, the one statement that is unquestionably true is that there is significant scientific evidence of Ivermectin’s efficacy.

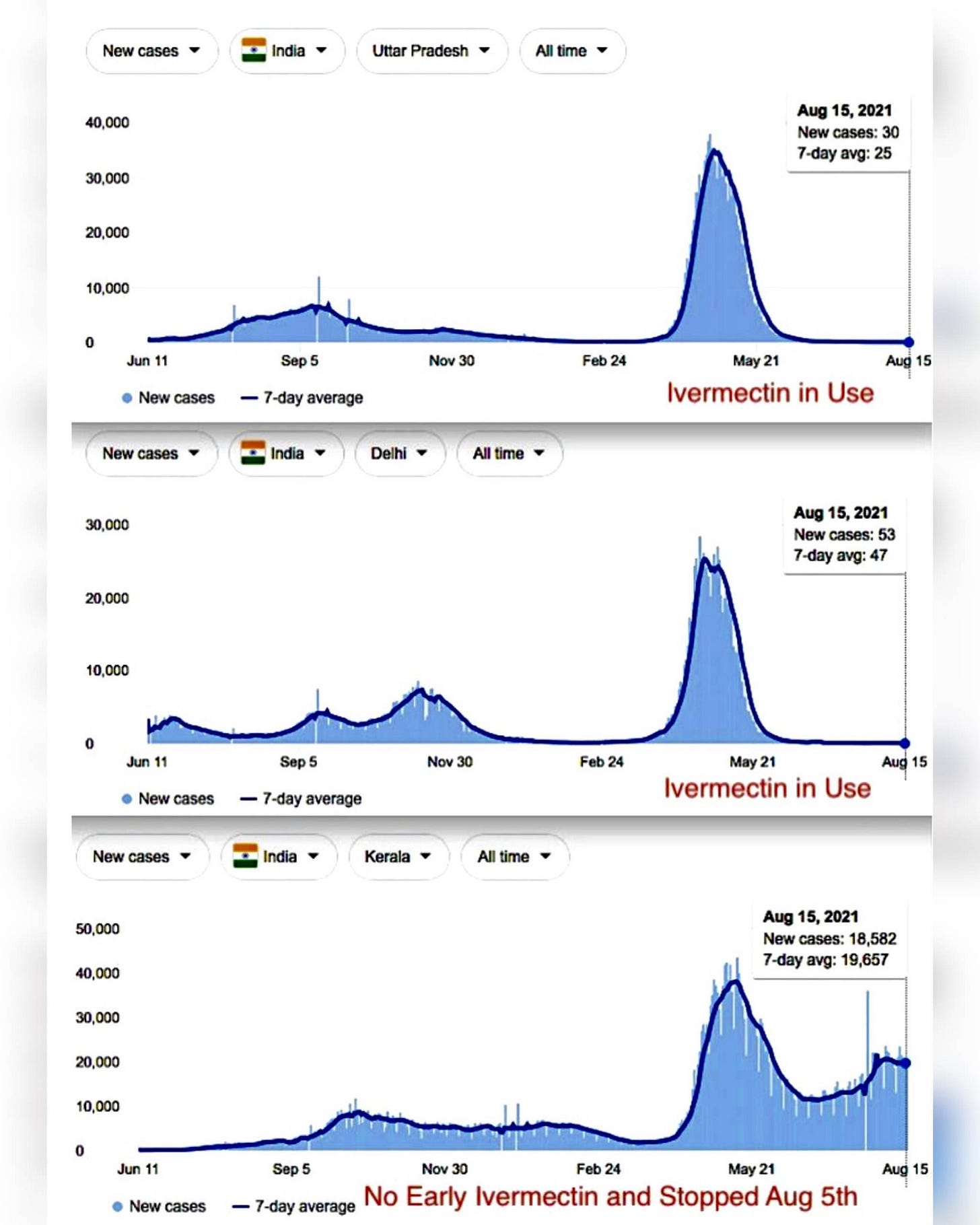

Moreover, these studies reflect the apparent real-world experience of India, which experienced a significant COVID-19 outbreak earlier this year in the state of Uttar Pradesh and responded by turning to Ivermectin (as well Hydroxychloroquine). As of the end of August, Uttar Pradesh is largely COVID-free, despite having one of the lowest inoculation rates in the world at 5.8%.

This means that 31.3% of the eligible population in state has taken at least one dose of vaccine while 5.8% are fully vaccinated. Officials pointed out that second dose vaccinations will pick up in August. On the other hand, 61 new cases were reported in the past 24 hours taking the total number of cases to 17,08,623. Of these, 16,85,170 have recovered including 45 in the past 24 hours. This speaks for a Covid-19 recovery rate of 98.6%.

While media outlets will endlessly “fact check” how the Uttar Pradesh results were obtained, the use of Ivermectin was specifically authorized and even recommended by India’s health agencies. With only 5.8% of the population inoculated even at the end of August, the inoculations certainly cannot claim credit for the abatement of the Uttar Pradesh outbreak. Ivermectin certainly seems to at least have contributed to the containment of the disease in Uttar Pradesh.

India’s experience in fact appears to show that Ivermectin may even achieve superior outcomes to the inoculations. While Utter Pradesh has contained its COVID-19 outbreak, as has the state of Delhi, the much smaller Indian state of Kerala, which has relied more on inculations, has had a much less favorable experience.

There is another important factor to consider: cost. Generic Ivermectin costs around $45 in the United States for a 3-day regimen, and can be had for even less elsewhere in the world. An effective low-cost therapeutic for COVID-19 is an undeniable blessing to the world’s many impoverished countries. While the prices for Merck’s antiviral are as yet unknown, it is highly unlikely that it will be price competitive with Ivermectin.

Curiously, Ivermectin may also be the inspiration for Pfizer’s anti-Covid medication. Research indicates Ivermectin functions as a protease inhibitor, blocking key proteins involved in SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Ivermectin was found as a blocker of viral replicase, protease and human TMPRSS2, which could be the biophysical basis behind its antiviral efficiency.

Pfizer’s own press release on the upcoming Phase 2/3 study of its drug candidate, PF-07321332, state explicitly the drug is also a protease inhibitor.

While this has led some people to erroneously conclude that PF-07321332 is merely repackaged Ivermectin, what the Pfizer trials do show is that there is merit in the protease inhibition approach to treating COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2 infection. If that is true—and we must conclude that Pfizer at the very least finds the approach worthy of study—then the capacity of Ivermectin to also act as a protease inhibitor further establishes the potential of the drug as a COVID-19 therapeutic.

Remember Hydroxychloroquine?

Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) has an even longer history of FDA approval (and success in treating parasitical infections) than Ivermectin. HCQ is the latest chemical analog to quinine, which has been used to combat malaria and other parasitical infections for hundreds of years.

Quinine was first recognized as a potent antimalarial agent hundreds of years ago. Since then, the beneficial effects of quinine and its more advanced synthetic forms, chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine, have been increasingly recognized in a myriad of other diseases in addition to malaria. In recent years, antimalarials were shown to have various immunomodulatory effects, and currently have an established role in the management of rheumatic diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis, skin diseases, and in the treatment of chronic Q fever.

The use of HCQ to treat auto-immune disorders such as lupus is particularly noteworthy, as it shows the drug having significant impact on the human immune system.

What is also worth noting is that, as far back as 2005, HCQ’s chemical cousin Chloroquine was found to be effective against another coronavirus infection of note: the original SARS.

We report, however, that chloroquine has strong antiviral effects on SARS-CoV infection of primate cells. These inhibitory effects are observed when the cells are treated with the drug either before or after exposure to the virus, suggesting both prophylactic and therapeutic advantage. In addition to the well-known functions of chloroquine such as elevations of endosomal pH, the drug appears to interfere with terminal glycosylation of the cellular receptor, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. This may negatively influence the virus-receptor binding and abrogate the infection, with further ramifications by the elevation of vesicular pH, resulting in the inhibition of infection and spread of SARS CoV at clinically admissible concentrations.

Chloroquine was also identified as a potential therapeutic for the MERS coronavirus, which emerged in the Middle East in 2012.

We identified four compounds (chloroquine, chlorpromazine, loperamide, and lopinavir) inhibiting MERS-CoV replication in the low-micromolar range (50% effective concentrations [EC50s], 3 to 8 μM).

Hydroxychloroquine is generally considered equipotent to Chloroquine, but has the advantage of being less toxic and thus safer to administer.

Unsurprisingly, given its much longer history, HCQ has a larger body of research evidence regarding its efficacy against COVID-19 than Ivermectin as well, with some 290 separate studies as of September 29, 2021, including 44 Randomized Controlled Trials. Like Ivermectin, HCQ shows significant efficacy against COVID-19.

•97% of the 32 early treatment studies report a positive effect (13 statistically significant in isolation).

•Meta analysis using the most serious outcome reported shows 64% [54‑71%] improvement for the 32 early treatment studies. Results are similar after exclusion based sensitivity analysis and after restriction to peer-reviewed studies. Restricting to the 8 RCTs shows 46% [16‑65%] improvement, and restricting to the 13 mortality results shows 75% [60‑84%] lower mortality.

•Late treatment is less successful, with only 68% of the 196 studies reporting a positive effect. Very late stage treatment is not effective and may be harmful, especially when using excessive dosages.

•83% of Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) for early, PrEP, or PEP treatment report positive effects, the probability of this happening for an ineffective treatment is 0.0038.

Even looking at just the 44 extant Randomized Controlled Trials, HCQ shows a 46% improvement in patient outcomes in early treatment. Although late treatment is considerably less effective, with only a 17% improvement, it is at least somewhat effective even at that stage of the disease. HCQ seems less effective at prophylaxis than Ivermectin, reporting only a 19% improvement for Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis and 26% improvement for Post-Exposure Prophylaxis. Overall, HCQ accounts for a 26% improvement vs the controls used in RCTs.

With scientific research indicating efficacy against SARS and MERS, and extensive clinical study showing efficacy against SARS-CoV-2, the body of evidence supporting the efficacy of HCQ as an antiviral and in particular in treating COVID-19 is quite substantial.

No Magic Bullets

We should note that neither Ivermectin nor Hydroxychloroquine are 100% effective against the SARS-CoV-2 virus. We should acknowledge that neither the Merck nor the Pfizer antiviral candidates are 100% effective against the SARS-CoV-2 virus. These drugs are not now, have never been, and never will be “a cure” for COVID-19.

Similarly, the current inoculations produced by Pfizer and other pharmaceutical companies are not 100% effective at stopping either SARS-CoV-2 infection or transmission. The current debates over booster shots for these inoculations, and Pfizer’s own ongoing research into antiviral treatments for the disease, are absolute proof of the limitations of the inoculations against COVID-19.

These are therapies and preventatives. They are not “magic bullets”. There is no magic bullet against COVID-19, and it is highly unlikely there will ever be a magic bullet against COVID-19.

Yet Merck and Pfizer demonstrate that effective therapeutics against the SARS-CoV-2 virus are possible. They demonstrate that inoculations are not the only healthcare option available. They demonstrate that we owe it to ourselves to examine all the healthcare options, to scrutinize and contextualize the available data, and to make full use of all potential therapies and remedies.

They demonstrate that we need to give a closer look to Ivermectin and Hydroxychloroquine.

This is about my month long ordeal with shingles. Make of it what you will. When the rash appeared and it was correctly diagnosed, I was given Valacyclovir. It is the first antiviral I've taken. It made me so nauseous that I couldn't eat. I couldn't continue taking them. And it really didn't seem to be doing much. I started ivermectin/HCQ in the doses recommended for an active Covid case, plus zinc and magnesium. I have no problems tolerating it and it seems to quiet the nerves. I would like to see real tests for these drugs, for some of the off label uses.