Yesterday’s economic data was an object lesson in how the Fed should not approach inflation and recession.

Yet it would be a mistake to presume the Fed’s mistakes are confined to just its ham-handed approach to inflation and interest rates. Indeed, the policy of error has been the centerpiece of Federal Reserve monetary policy for at least the past 25 years (arguably longer), and are part and parcel of the parlous state of financial markets today (as recent declines of both the Dow Jones and S&P 500 indices attest).

To more fully apprehend just how wrong the Fed is today, we do well to consider just how wrong the Fed has been all along.

1997: Where We Begin, But Not The Beginning

While there is nothing particularly special about 1997, economically speaking, going back that far lets us see some of the historical trends that have brought the Federal Reserve to its current crossroads.

It would be a grievous error to say that the Fed’s policy mistakes began in 1997—many if not most arguably go back even farther than that. Yet by choosing 1997 as the starting point for this discussion, we can see at least some of the trends building up into the to significant recessions prior to 2020, and can see how the Fed’s money manipulations have mutated since.

Thus, 1997 is where we begin. The reader is cautioned not to consider it “the beginning”.

Perhaps the most significant thing to understand about 1997 is that inflation at the time was generally perceived to be low and not much of a problem.

Indeed, a number of Fed observers at the time took then-Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan to task for being too focused on inflation, at the expense of worker’s wages and opportunities for economic advancement.

From March of that year:

The only risks Mr. Greenspan sees are these: First, a continued tight labor market. Second, the rising minimum wage later this year. And third, the possibility that ''larger increases in fringe benefits could put upward pressure on overall compensation.''

The gentleman could not have been more clear. He is not concerned about inflation. He is concerned about the possibility, remote and uncertain though it is, that the American worker might start to demand, and receive, a slightly bigger share of the economic growth that has occurred over the past seven years.

Given Richmond Fed President Tom Barkin’s recent comments about the need to raise interest rates to “slow down hiring”, such criticisms have a distinct ring of familiarity to them.

Yet Greenspan should get at least this much credit—at least he was taking the prospect of renewed inflation seriously. The same cannot be said of his successors as Fed Chair.

However, that is not to say that Greenspan kept interest rates high—although by today’s standards they were at stratospheric levels, with 10-Year Treasury Yields moving from ~6.75% to ~4.5% between 1997 and 1998.

Arguably, his steering interest rates generally lower during that period helped fuel the tech stock bubble that precipitated the 2001 recession. Moreover, between late 1998 and 2000, Treasury yields rose to near the 1997 high of 6.75%—the last time interest rates would be even close to this level—thereby reversing the “easy money” policy of the prior period.

More ominously for markets, in 2000 the 2-Year Treasury Yield “inverted”, rising higher than the 10-Year Yield (as a rule the 2-Year is lower than the 10-Year), a technical indicator of pending recession according to many economists.

In 2001, the bubble was well and truly popped, and stock prices headed down.

Stock Prices Were Not Being Driven By Money Supply—Yet

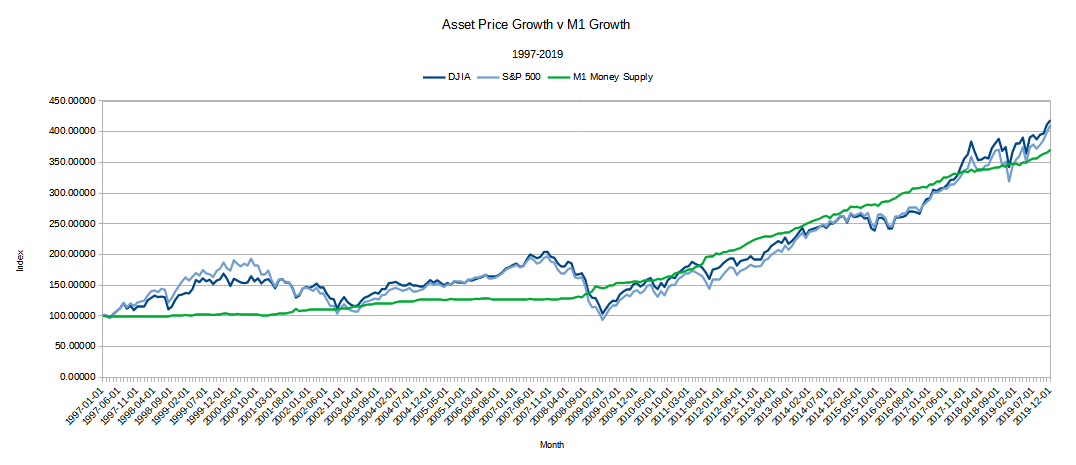

Regardless of the merits and demerits of Greenspan’s handling of interest rates and monetary policy, this much is demonstrably true: stock prices moved largely independently of the growth of the overall money supply (M1). We can establish this absolutely by noting the magnitude fluctuations in both the money supply and both the Dow Jones and S&P 500 stock market indices, and that the Dow Jones fluctuations have a correlation coefficient to growth in the M1 of 0.58226, with the S&P showing even less correlation at 0.26670.

(Note on analytical technique: the magnitudes of change in each data series is compared directly by restating each data series as an index number, with the value as of January 1, 1997, having the index value of 100 for each series. The index values thus derived are mathematically equivalent to percentage levels of that index date).

Through the tech stock bubble and 2001 recession, and in the run-up to the 2008 Great Financial Crisis and subsequent recession, these relatively low correlations would prevail. Growth in the money supply was putting upward pressure on asset prices, but true price discovery and market mechanisms were demonstrably at work. That would change in 2008.

When we look at changes in asset price growth vs M1 money supply growth on an index basis, we see the moves in stock indices pre-2008 showing clear signs of independence from the money supply.

However, from 2008 onward, the growth in the money supply correlates quite strongly to the growth in asset prices. Between 2008 and 2019 the correlation coefficient between growth in the Dow Jones and growth in the money supply is 0.95082, and between the S&P 500 and the money supply the coefficient is 0.96142.

During these years growth in money supply accounts for almost all increases in asset prices. In fact, it is extremely likely that, without the accelerated growth in the money supply during this period, asset prices would actually have fallen, as the magnitude of money supply growth outpaced both the DJIA and the S&P500.

What makes this shift even more significant is that an opposite shift occurred with the most commonly reference inflation metric, the CPI. Its growth rates prior to 2008 track very closely with growth rates in the money supply, yet after 2008 the money supply increased dramatically with no shift of corresponding magnitude in the CPI.

2008: The Dawn Of The Magic Money Printing Press

2008 also marks the beginning of a dramatic shift in Federal Reserve policy, where the money supply was dramatically expanded, first through extreme interest rate reductions and then through a policy of “quantitative easing”—large scale asset purchases by the Federal Reserve.

The first expansionary influence was the slashing of the Federal Funds Rate—the Fed’s one direct lever on interest rates (and, by extension, the money supply). In January, 2007, the Federal Fund Rate peaked at 5.33%—a full half percentage point higher than the 10-Year Treasury Yield at the time—and by January, 2009, the Federal Funds Rate had fallen to 0.23% (10-Year Treasury Yields stayed modestly higher at 2.87%).

The second expansionary influence was the advent of formal quantitative easing by the Fed. Between 2009 and 2014, the Federal Reserve would conduct three rounds of asset purchases in the open market, each one justified by a need to “foster improved conditions in financial markets”.

Additionally, by 2009 there is a distinct shift in Fed thinking. Whereas the Greenspan era was characterized by a desire to keep inflation low, his successor Ben Bernanke was worried that inflation might be too low.

In light of the declines in the prices of energy and other commodities in recent months and the prospects for considerable economic slack, the Committee expects that inflation pressures will remain subdued in coming quarters. Moreover, the Committee sees some risk that inflation could persist for a time below rates that best foster economic growth and price stability in the longer term.

Thus the Federal Reserve embarked on a decade-long pattern of rapid increases in the M1 money supply, motivated in part by a desire to actually increase inflation.

However, as we can see when we compare CPI growth to M1 money supply growth, the desired inflation simply didn’t happen.

What Happened?

A full exploration of why the desired inflation did not materialize would require multiple Substack articles all by itself. However, even without a detailed explanation of the forces driving the result, we can safely identify two phenomena which worked at cross-purposes to the Federal Reserve’s inflation objectives.

The first is the rise in asset prices charted above. The strong correlation signal between asset prices and the money supply tells us that while the Fed was quite successful in goosing money supply, it was unsuccessful at circulating that money out into the general economy. Rather, the newly created money stayed within financial markets, fueling the record DJIA and S&P500 index levels that have been achieved since 2008.

The second phenomenon is likely tied to the first: a steep decline in the overall velocity of money within the US economy.

Close scrutiny of the M2 money supply velocity shows that it had actually been in decline since the 3rd quarter of 1997, which downward trend has been more or less steady ever since. However, the M1 velocity increased up until the 2008 recession and then entered a sharp decline through the rest of the decade.

Money supply velocity measures how much (and how rapidly) money flows through an economy. In theory, money supply velocity is increased in more developed economies and decreased in less developed economies, in proportion to the amount of money consumers and businesses have to spend. Additionally, higher money supply velocities are positively correlated with increases in consumer price inflation (broadly speaking, the more people are spending, the more there is demand, and the greater that prices are bid up throughout the economy).

Money supply velocity is also a traditional gauge of whether an economy is expanding or contracting.

Yet while the Fed was expanding the money supply post-2008, money velocity kept decreasing. Again, the created money stock simply never left the financial markets. Instead, it fueled not the desired marginal consumer price inflation, but asset price inflation.

Did Jerome Powell Realize This In 2018?

While it would take the mental telepathy of a latter-day Kreminologist to fully divine Fed Chair Jerome Powell’s true thoughts and motivations, it is historical fact that in 2018 and 2019 Powell attempted to push interest rates back up—only to be forced to reverse course when financial markets entered into a brief bear market.

The relative wisdom or unwisdom of Powell’s attempted policy shift will be debated probably indefinitely—and should be, given the tendency of such policy shifts to catalyze market reversals and economic turmoil going all the way back to the Great Depression.

Still, Powell publicly asserted that stock markets and asset prices were “overvalued” in 2018, and, with logic much the same as Ben Bernanke used in 2006, intended to raise interest rates with the specific intent of cooling off those same markets (although the extent to which that is actually within the Federal Reserve’s brief is highly debateable, which was a large part of my reasoning at the time to be critical of the policy shift). Given the declining money velocities experienced since 2008, which thus “trapped” money within financial markets, there is a certain logic to the “overvalued” assessment. Certainly it is not irrational to conclude that markets were awash in “too much” money and liquidity, and that liquidity needed to be drained somehow.

Unfortunately, the markets have reacted to the sloshing around of money in a manner very much akin to drug addiction—now that they have it, they can no longer function properly without it. Even in 2018, there would likely have been no way for Powell (or anyone else) to remove any “excess liquidity” from the markets without also triggering broad declines in asset prices. Since the asset price rises were fueled in large part by the massive injection of money and liquidity, withdrawing it will inevitably trigger corresponding asset price declines.

To shrink the money supply, Powell must quite literally crash the markets.

Modern Monetary Insanity

Even before 2020’s massive expansion of the money supply, the trajectory of Federal Reserve policy had already led it into a policy trap with no easy way out. With markets utterly dependent on a steady flow of newly created money just to sustain price levels, there was no way for the Fed to even mildly address the money supply without wreaking havoc in financial markets.

At the same time, the only thing preventing the US from experiencing not merely the inflation levels of the late 1970s, but true “Weimar Republic” levels of hyperinflation, has been the decline of money velocity. If nothing else changes and money velocity increases, hyperinflation becomes a mathematical certainty.

All of which begs the question “what was the Federal Reserve thinking?”

Somehow, the Federal Reserve managed to forget the experience of the stagflation of the 1970s, along with the deep recession catalyzed by the Volcker interest rate hikes to overcome the double digit inflation of that era.

And we have yet to consider the events of 2020 and beyond.

That will be the focus of the second part of this discussion.