As Mark Twain once observed, “history doesn’t repeat itself but it does rhyme.”

With cases of monkeypox spreading throughout Europe and North America, the WHO’s history as a coordinator of global public health responses is certainly rhyming—with the ineptitude and chaos of its early COVID-19 response.

Then, the bureaucratic bungling revolved mainly around the WHO’s obsequious genuflecting to China and endless handwringing over not offending China with the name to be given to the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Now, the bureaucratic bungling revolves around more endless handwringing, this time over not offending African countries over the name of the virus and the disease (monkeypox).

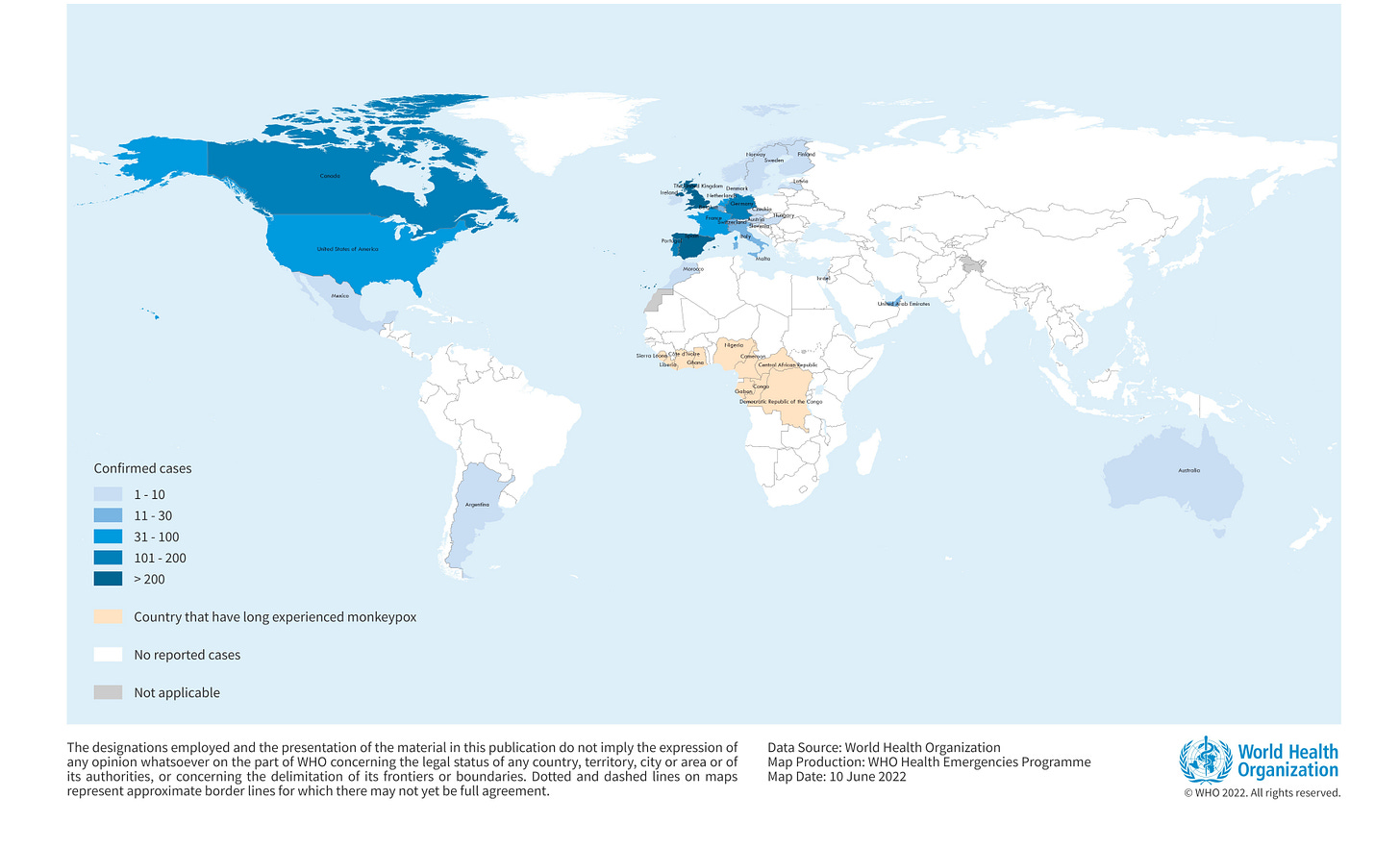

Meanwhile, evidence continues to mount that there is a definite shift in the virus’ pathogenicity. Something is definitely different about the monkeypox virus now spreading through Europe. The WHO even says as much within their roundabout descriptions of the spread of monkeypox in Europe vs the ongoing outbreak in Africa. Even their map presents as if there are two different outbreaks ongoing: one in Africa and one outside of Africa.

European Monkeypox Spreads Faster Than African Monkeypox

The most obvious difference between the recorded cases of monkeypox in Europe and North America vs the ongoing outbreak in West and Central Africa is the number of cases.

In the WHO’s most recent Disease Outbreak News bulletin on the global monkeypox outbreak, there are a total of 59 confirmed cases and 1,536 suspected cases of monkeypox within 8 countries in West and Central Africa, along with 72 deaths.

The bulk of the suspected cases as well as the deaths come from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. This is fairly unsurprising, as the Congo River basin is host to a clade of monkeypox known to be more transmissible and more lethal than West African clade found in Nigeria and surrounding countries.

All of these cases have been reported since January.

However, outside of Africa, there have been as of this writing 2,093 confirmed cases of monkeypox dated from May 6 onward. Adding suspected cases brings the total to 2,193.

As of June 13, there were more cases of monkeypox outside of Africa than within Africa, over a span of weeks rather than months.

Monkeypox is demonstrably spreading faster in Europe and North America than in Africa.

Additionally, the ongoing African outbreak of monkeypox appears to be primarily zoonotic—viral infection is from animals to humans—rather than human-to-human transmission. The African cases are primarily in rural and forest communities and deforestation as well as encroachment on animal habitats are being reported as key factors in the outbreak.

Most outbreaks across affected countries have occurred in hard-to-reach forest communities. An increase in the number of districts reporting cases since 2017 has been observed, indicating a geographic spread of the disease.

The European cases present as involving human-to-human transmission.

The sudden appearance and wide geographic scope of many cases that initially appeared to be sporadic cases indicate that extended human-to-human transmission was facilitated by frequent encounters between persons in close proximity and/or with physical contact.

This is quite a shift in the disease, as the only other major outbreak of monkeypox outside of Africa was the 2003 outbreak in the United States, and which was attributed to prairie dogs being caged close to animals from Africa carrying the virus and then sold as pets to unsuspecting individuals.

The CDC notes on its web site that no instances of monkeypox during the 2003 outbreak could be traced solely to human-to-human transmission.

European Monkeypox Looks Different From African Monkeypox

Additionally, as the WHO began to note in its Disease Outbreak News bulletin of June 4, the non-African cases frequently present differently. Most notably, the European cases frequently do not have the all-body rash common to orthopox viruses.

To date, the clinical presentation of confirmed cases has been variable. Many cases in this outbreak are not presenting with the classical clinical picture for monkeypox. In cases described thus far in this outbreak, common presenting symptoms include genital and peri-anal lesions, fever, swollen lymph nodes, and pain when swallowing. While oral sores remain a common feature in combination with fever and swollen lymph nodes, the local anogenital distribution of rash (with vesicular, pustular or ulcerated lesions) sometimes appears first without consistently spreading to other parts of the body. This initial presentation of a genital or peri-anal rash in many cases suggests close physical contact as the likely route of transmission during sexual contact. Some cases have also been described as having pustules appear before constitutional symptoms (e.g., fever) and having lesions at different stages of development, both of which are atypical of how monkeypox has presented historically. Apart from patients hospitalized for the purpose of isolation, few hospitalizations have been reported. Complications leading to hospitalization have included the need to provide adequate pain management and the need to treat secondary infections.

This departure from the classic presentation of monkeypox is noteworthy because the genomic sequencing done to date indicates the European infections stem from the West African clade of the virus.

Genomic sequencing of viral deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) of the monkeypox virus, where available, is being undertaken. Several European countries (Belgium, France, Germany, Israel, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain, Switzerland and the United States of America) have published full-length or partial genome sequences of the monkeypox virus found in the current outbreak. While investigations are ongoing, preliminary data from PCR assays indicate that the monkeypox virus genes detected belong to the West African clade.

WHO Is Stuck In The Past

Despite the clear distinctions between the European cases and the African cases of monkeypox, the WHO’s most recent setting of research priorities remains mired in the apprehension of monkeypox as being endemic to West and Central Africa.

Improved control of monkeypox in endemic countries is critical to address increases in disease incidence, and to control importations and outbreaks elsewhere. Participants agreed that strengthened collaboration among researchers in endemic countries, who have a wealth of experience and data on the disease – along with researchers from other countries – will ensure that scientific knowledge advances more quickly.

This stands at odds not only with their own published statistics on monkeypox cases in and out of Africa, but also is in significant contrast to published observations made by several independent researchers.

While early genomic evidence connects the European cases to the a strain of monkeypox within the West African clade and associated with the “exportation” of cases fo Israel, Singapore, and the UK in 2017-2018, further analysis has also identified 47 single nucleotide substitutions which distinguish it from earlier exemplars of that strain of the virus.

The first MPXV genome sequences from monkeypox cases in 2022 (Isidro et al. 2022; Selhorst et al. 2022) showed, phylogenetically, that these viruses had descended from a clade sampled in 2017-2019 from cases diagnosed in Singapore, Israel, Nigeria and the UK. Comparing 2022 genomes from Portugal, Belgium, USA, Australia, and Germany (see Table 1) with the closest earlier genomes (denoted UK_P2 and UK_P3), identified 47 shared single nucleotide differences (Figure 1).

As I noted last week, this number of mutations is as much as 6 or 7 times the number of mutations one would expect given an historical rate of mutation of one or two nucleotide substitutions per year.

Despite the WHO referencing the Rambaut and O’Toole research documenting the unusually large numbers of mutations in their June 4 bulletin, no mention of following up on that research or its potential significance in possible shifts in pathogenicity was made in their outlined research priorities published just one day earlier.

Based on those priorities, the WHO is continuing to regard monkeypox monolithically as the zoonosis it historically has been, despite clear and mounting evidence that, particularly in Europe, the zoonotic model does not describe current modes of transmission.

The WHO Prefers Political Grandstanding To Actual Research

Amazingly, the WHO’s greatest priority seems to be finding a suitable new name for monkeypox, as the name “monkeypox” has been deemed a “stigma” to the peoples of West Africa. This despite the lack of strong evidence—or indeed of any evidence—of such stigmatization or prejudice in the extant media reporting of monkeypox cases.

In true genuflection to the altar of political correctness, the WHO is devoting at least some brain cells to the creation of a new name for the virus and the disease.

The World Health Organization has said it will rename monkeypox to avoid discrimination and stigmatisation as the virus continues to spread among people in an unprecedented global outbreak of the disease.

Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the WHO’s director general, said the organisation was “working with partners and experts from around the world on changing the name of the monkeypox virus, its clades and the disease it causes”.

The perverse irony, of course, that the one place that most clearly articulates that monkeypox is endemic to West and Central Africa is…wait for it…the WHO.

From their June 4 Disease Outbreak News Bulletin:

Monkeypox endemic countries are: Cameroon, the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Gabon, Ghana (identified in animals only), Cote d’Ivoire, Liberia, Nigeria, the Republic of the Congo, and Sierra Leone. Benin and South Sudan have documented importations in the past. Countries currently reporting cases of the West African clade are Cameroon and Nigeria.

By June 10, their language on the African cases was modified:

The case fatality ratio seen in the African Region underlines the need for support for all elements of the response including but not limited to, awareness-raising, risk communication, surveillance, diagnostic and laboratory support, and research and analysis in the Region. WHO is providing guidance and reporting forms to countries that have long experienced monkeypox as well as countries that have newly been affected.

The “countries that have long experienced monkeypox” are, of course, the countries where monkeypox is endemic. That is the essence of the definition of “endemic”

1a : belonging or native to a particular people or country

b : characteristic of or prevalent in a particular field, area, or environment

Yet the fundamental flaw in such virtue-signaling is that it not only overlooks but obscures the very real and marked differences between monkeypox cases in Africa and Europe. It flat-out ignores the extraordinary number of mutations present in the strains circulating in Europe and North America. It completely disregards the epidemiological reality (which even the WHO acknowledges) that a majority of the cases in Europe and North America involve gay and bisexual men—”men who have sex with men” in the current PC argot.

As even the WHO has suggested, and as Rambaut and O’Toole’s research largely confirms, the European cases are coming at the end of what has to be accounted as a lengthy but undetected period of sustained human-to-human transmission. That by itself is a strong signal the monkeypox virus is endemic to Europe and has been for some time.

While it is astounding that a disease with marked physical symptoms such as rashes and lesions could circulate undetected, particularly in Europe where healthcare infrastructures are far more comprehensive than in Africa, at the present time the extant data points to exactly that having occurred. The European cases might have started as an offshoot of the variant associated with the “exported” cases from Nigeria in 2017-2018, but they are the result at the very least of an extended circulation outside of Africa. Arguably, the European cases represent their own clade and warrant their own phylogeny.

The reality of the global spread of monkeypox is that the virus has shifted, mutated, and evolved. It is changing from a zoonotic disease to a contagious disease. Science and medicine must acknowledge this shift and adapt research priorities and protocols to match the virus as it is today.

The reality of the WHO is that the organization remains mired in the perceptions and politics of the past, and has yet to adapt to the present reality of monkeypox in Europe.

Don't "monkey it up."

--Ron DeSantis

Not sure how to read the description of an apparently more subtle disease. Could be much of what is being seen now in Europe, etc. goes completely undetected where endemic? Could have been brewing in Europe for a long time, not seen but secretly spread in covid lockdown years?

At least does not look like an unconstrained exponential in terms of growth. Maybe even rolling over already in some countries