As of this writing, the world is still assessing whether the June 21 attacks on Iran’s nuclear facilities did all the damage President Trump has claimed that it did.

Yet even as the damage assessment information starts to flow, the US and the world must grapple with the potential ramifications of Trump’s decision to have the US directly attack Iran.

Did President Trump end a potential threat? Is peace now more or less likely?

Was the attack itself, dubbed Operation Midnight Hammer, even legal, given the Constitutional divisions of authority between Congress and the President over the use of US military force?

With events still unfolding as of this writing, there is much that may change about what is known of the attack, its effects, and its consequences. However, with what is known at this time, we may still construct a broad framework for assessing what transpired and why.

Contents:

Did President Trump Have The Authority?

Many commentators both in and out of government have decried Operation Midnight Hammer as a case of President Trump exceeding his Constitutional authority.

As I noted last night, contrarian Republican Thomas Massie posted on X that he did not deem the attack to be Constitutional.

Progressive Democrat Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez called for President Trump’s impeachment.

A number of my own readers have expressed similar opposition.

The actual legal situation, however, is not quite so clear.

The legal foundation for Presidential actions to use military force stems from the War Powers Resolution of 19731. Specifically, Section 2(c) of the act2 establishes presumptively clear statutory limitations on Presidents committing the Armed Forces to hostilities.

The constitutional powers of the President as Commander-in-Chief to introduce United States Armed Forces into hostilities, or into situations where imminent involvement in hostilities is clearly indicated by the circumstances, are exercised only pursuant to (1) a declaration of war, (2) specific statutory authorization, or (3) a national emergency created by attack upon the United States, its territories or possessions, or its armed forces.

We should note that the Executive Branch has never viewed Section 2(c) as a significant impediment to Presidential action involving the Armed Forces, as a Reagan-era Office of Legal Counsel Memorandum3 makes clear:

The Executive Branch has taken the position from the very beginning that §2(c) of the WPR does not constitute a legally binding definition of Presidential authority to deploy our armed forces. The Department of State’s position set forth in a letter of November 30, 1973 was that § 2(c) was a “declaratory statement of policy.”

As Reagan’s 1986 bombing of Libya4 and Bill Clinton’s missile strike on Sudan in 1998 illustrate, when Presidents believe they have reason to strike a particular target, they do so, without much concern over the technicalities of Section 2(c) of the War Powers Resolution.

However, there may very well be sufficient statutory authorization already granted by Congress legitimizing Trump’s attack on Iran’s nuclear facilities. Specifically, the Authorization To Use Military Force5 passed by Congress in the wake of 9/11 has fairly broad language on the types of military actions the President may initiate.

That the President is authorized to use all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations, or persons he determines planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001, or harbored such organizations or persons, in order to prevent any future acts of international terrorism against the United States by such nations, organizations or persons.

While this AUMF was initially passed to allow President Bush to pursue al-Qaeda and the Taliban in Afghanistan, President Obama used it to justify military operations in Iraq and Syria against ISIS—which continues today as Operation Inherent Resolve—and as the legal pretext for the 2016 bombings of Islamic State targets in Libya.

These justifications are not without their challenges, however. Legal scholars such as Jens David Ohlin, writing in OpinioJuris, flatly rejected the premise that the 2001 AUMF extended to cover offshoots of al-Qaeda.

Yes, ISIS once had a relationship with al-Qaeda and Osama Bin Laden, but that prior relationship no longer governs. What matters is the current relationship. Furthermore, the fact that ISIS is the “true inheritor” of Bin Laden’s legacy is neither here nor there. In what sense is ISIS the “inheritor” of Bin Laden’s legacy? The only one I can think of is that ISIS represents the gravest Jihadist threat to the peaceful world — a position once held by Osama Bin Laden. Also, the fact that they threaten U.S. personnel and interests is an argument that proves way too much — plenty of other groups do that as well, which isn’t terribly relevant. None of this makes ISIS fit into one of the AUMF categories (planning, aiding, haboring, etc). Simply put, ISIS is not al-Qaeda.

By similar logic, Iran is not Afghanistan.

Yet Obama’s use of the AUMF to justify further military actions in the Middle East largely went unchallenged. In 2016, in an article initially appearing in the American Journal of International Law6, University of Chicago professors Curtis Bradley and Jack Goldsmith concluded that part of Obama’s presidential legacy was to have expanded the scope of the 2001 AUMF to an almost infinite degree.

In a real sense, then, the 2001 AUMF is President Obama's AUMF. Despite his frequent rhetoric about ending the AUMF-authorized conflict, part of Obama's legacy will be cementing the legal foundation for an indefinite conflict against various Islamist terrorist organizations.

However, this expansion does not rest entirely on Barack Obama’s shoulders. Congress repeatedly declined either to pass new authorizations or to curtail the 2001 AUMF in response to Obama’s reliance on the Bush-era authorization to justify military endeavors throughout the Middle East.

It is challenging to argue that President Trump does not have the same scope of authority Congress was willing to allow President Obama under the rubric of a statutory authorization initially granted to President Bush, when Congress has not updated that authorization.

I will note that I have in the past argued against the continued reliance on the Bush-era AUMFs for justifying virtually any military operation in the Middle East or elsewhere.

On that authority has rested all US troop deployments to the Middle East since. Barack Obama used the Bush-era authorizations during his Administration, and President Trump has continued that unconstitutional policy. The Congress has actually encouraged this, despite its obvious Constitutional defects.

In truth, Congress has always been tolerant of Presidents waging undeclared war. In the whole of American history Congress has issued only 11 formal declarations of war, and 6 of those involved the hostile powers in World War Two. The bloodiest of all US wars, the Civil War, is not among the 11 declarations. The assault on the Barbary Pirates immortalized in the Marine Corps Hymn ("to the shores of Tripoli") was undeclared, as were the interventions in Korea and Vietnam. Our longest and costliest expenditures of blood and treasure have never been sanctioned by formal declarations of war issuing from the Congress.

Put another way, our longest and costliest expenditures of blood and treasure arguably have been illegal and unconstitutional.

While the legal and Constitutional arguments against President Trump having the authority to order Operation Midnight Hammer are substantial, the legal reality is that, historically, those arguments have failed to persuade.

Certainly, Congress has failed completely to defend its Constitutional prerogatives in this area. As the late Justice Antonin Scalia noted in his concurrence in United States v Irvine7, there is legal substance to the doctrine “qui tacet, consentire videtur” ("he who is silent is taken to agree”). By refusing to take action even to limit the scope of the 2001 AUMF, or to reject earlier reliances by President Obama on that AUMF, Congress has potentially legitimized its expanded usage, arguably ceding to the President its Constitutional authority even to declare war.

Where that leaves President Trump’s actual authority is left for the reader to decide.

Is Iran A Threat To The US?

Legal questions of authority aside, the operative factual question is whether or not Iran’s nuclear weapons program constituted any sort of threat to the United States.

Readers will note that I am referring to Iran’s nuclear enrichment activities as a nuclear weapons program. That is not accidental.

Iran is not merely enriching uranium to increase the concentration of the radioactive U-235 isotope. Iran is producing quite a bit of highly enriched uranium, and while it claims that its aims are entirely “peaceful”, it has been decidedly less than cooperative with the International Atomic Energy Agency on establishing either what those peaceful purposes are, or implementing safeguards with the IAEA to ensure the enrichment remains “peaceful.”

In a May 31 report to the IAEA Board of Governors8, IAEA Director General Rafael Grossi reported that Iran was producing 34kg of 60% enriched uranium each month, and had accumulated 408.6kg of 60% enriched uranium.

Civilian nuclear reactors typically use uranium enriched to only 3%-5%9, and only a few research reactors utilize highly enriched uranium for producing medical-related istopes.

Iran is producing highly enriched uranium at levels that exceed all plausible needs for a civilian nuclear power program or a nuclear medicine program.

In a separate report also dated May 3110, the IAEA concluded that Iran has been conducting an “undeclared structured nuclear programme”, and has been doing so for decades.

The thrust of the two reports is a very substantial and fact-based challenge to Iran’s assertions that its nuclear program is “peaceful.”

While many of the findings relate to activities dating back decades and have been made before, the IAEA report's conclusions were more definitive. It summarised developments in recent years and pointed more clearly towards coordinated, secret activities, some of which were relevant to producing nuclear weapons.

With this as the assessed backdrop by the IAEA, how should a President of the United States view televised statements by Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei that “Death to America” is, in fact, Iranian policy?

The situation between America and Iran is this: When you chant 'Death to America!' it is not just a slogan – it is a policy. I have stated the reasons previously. For many years, from the 1940s to the 1970s – that is 30 years – the Americans did everything they could do against the Iranian nation. They hit Iran in any way they could – financially, economically, politically, scientifically, and morally.

Moreover, we need to not overlook the reality of the dangers highly enriched uranium itself presents. Iran does not need to consolidate its stockpile of enriched uranium into a series of nuclear weapons to present a strategic threat to the United States or to any other nation. Just the enriched material itself can be utilized to produce “radiological weapons”—so-called “dirty bombs”.

The IAEA identified such weapons as a potential threat of nuclear terrorism as far back as 2005.

The IAEA has categorized four potential nuclear security risks: the theft of a nuclear weapon; the acquisition of nuclear materials for the construction of nuclear explosive devices; the malicious use of radioactive sources — including in so-called "dirty bombs"; and the radiological hazards caused by an attack on, or sabotage of, a facility or a transport vehicle.

Historically, the general perception of the threat of radiological weapons has been relatively low11, with the belief that the explosive spread of radioactive material would be limited in scope by the very nature of such devices. However, “low threat” is not the same as "no threat”.

Would Iran gift a portion of its store of highly enriched uranium to Hamas, Hezbollah, or one of its other terror proxies, to create a nuclear terror event either in the Middle East or elsewhere? There is, of course, no way to answer that question definitively—but can a President of the United States afford to take that chance?

Nor is this simply a question of the US or the IAEA meddling in Iranian internal affairs. Iran ratified the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty in 1970, Article III of which obligates non-nuclear weapons states such as Iran to cooperate with the IAEA to ensure proper safeguards are in place to prevent the conversion of nuclear energy programs from civilian to military purposes.

The IAEA reports over the years have been a consistent documentation of Iran’s refusal to measure up to its NPT Article III commitments.

If it had become known prior to Israel’s initial attacks last week that Iran was in possession of a functioning nuclear weapon, or even several such weapons, would people in the United States feel more or less safe?

The answer to that question is the extent to which Iran’s non-compliance with its NPT Article III commitments poses a strategic threat to the United States, and is the extent to which Iran’s uranium enrichment activities may be accurately described as a nuclear weapons program.

Iran Will Retaliate…But How?

As of this writing, Iran has yet to retaliate against the United States for Operation Midnight Hammer.

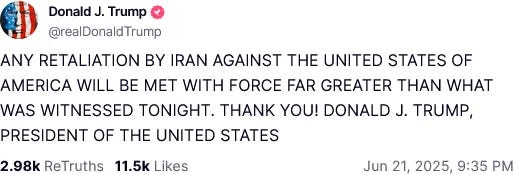

President Trump last night, and Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth again this morning, warned Iran against any such retaliation.

Despite such warnings, retaliation should be expected.

Already, the Iranian Parliament is calling for Iran to close the Strait of Hormuz, the channel between the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman. With 20% of the world’s oil traversing the Strait, even a brief disruption of oil shipments would send oil prices skyrocketing, potentially sparking a renewed hyperinflation cycle in the United States and elsewhere.

Can Iran maintain such a closure in the face of a US Naval presence in the Persian Gulf? That seems unlikely, although if it was maintained for even a few days the impact on oil prices could reverberate for far longer than that.

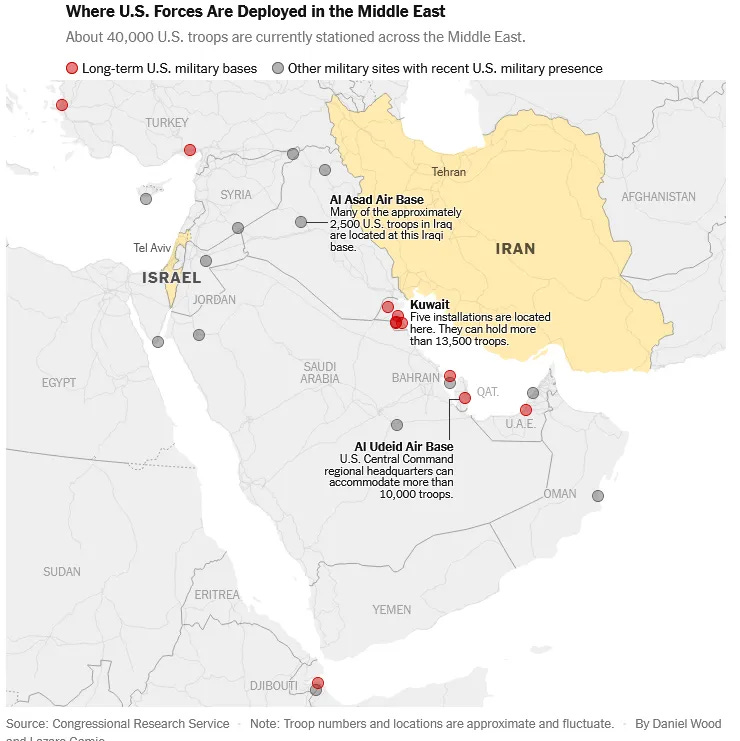

Iran could attempt missile and/or drone attacks on US bases and personnel in the region. With some 2,500 troops stationed in Iraq, and a total of around 40,000 stationed throughout the Middle East, Iran has no shortage of tempting US military assets to attack.

Such retaliations would almost assuredly spark further reprisal attacks by the United States, as President Trump has stated repeatedly.

There is also a concern that Iran may attempt a retaliation via one of its proxy terrorist groups, such as Hamas or Hezbollah. That may be a more problematic approach for Tehran, as Hezbollah particularly has shown little appetite for getting involved in this latest conflict, with Hezbollah sources reportedly claiming that “Iran can defend itself”.

With Iraq’s Kataib Hezbollah (no relation to Hezbollah in Lebanon) calling Israel’s attacks on Iran “deeply regrettable”, but announcing no intent to retaliate against either Israel or the United States, there is more than a little doubt that Iran’s proxies are up for any sort of conflict with either the US or Israel at this time.

The natural expectation is that “something” will happen, and soon, but in light of Israel’s success thus far in its air war against Iran, what Iran’s remaining capacities for retaliation might be makes assessing what retaliatory measures are more or less likely somewhere between difficult and impossible.

“Another War”?

The concern on the minds of many is that this attack by the US is the prelude to yet another extended US engagement in the Middle East.

It would be folly to rule out such an outcome, but we should also note that President Trump’s position has been focused and explicit: Iran cannot obtain nuclear weapons. Beyond that, Trump has explicitly declaimed any desire for a protracted war with Iran.

As many on X have noted, President Trump has been explicitly opposed to Iran obtaining nuclear weapons, and his position that Iran’s enrichment activities are a nuclear weapons program in violation of the NPT predates his first term as President.

None of this can be taken as assurance that Operation Midnight Hammer will not become yet another “forever war” in the Middle East, but it can be taken as President’s Trump sincere desire that such a war not emerge from this.

A great deal will depend on whether or not the attacks particularly on the Fordow facility were as devastating as Trump has claimed.

Various Iranian sources are claiming the damage was in fact largely superficial. Others are claiming the site had been evacuated in anticipation of a US attack, thus the potential for significant damage was largely eliminated.

Satellite imagery does show a significant amount of activity around the Fordow site last week, suggesting supplies, records, equipment, or perhaps even the store of highly enriched uranium was removed from the site prior to the US attack.

Yet if the site’s centrifuge cascades—which likely could not be quickly removed—have been damaged, then even with the materials that were removed Iran may find it difficult to resume its enrichment operations.

If Iran’s enrichment efforts have been brought to a standstill then President Trump’s attack objectives have largely been met.

That will not end Iran’s interest in nuclear weapons.

Even before Israel attacked, Iran responded to the IAEA’s latest censure by threatening to withdraw from the NPT. In the days following Israel’s opening strikes, the Iranian parliament prepared a bill to formally do just that.

Assuming the current regime remains stable and intact, it is reasonable to presume that Iran will do exactly that.

Where will that leave the Middle East? Where will that leave the wider world?

At this juncture, there is no way to predict such outcomes. Only one other nation has withdrawn from the NPT—North Korea, which was a largely isolated nation prior to its withdrawal and has been regarded as a pariah state since.

Would Iran be similarly isolated? Probably not, as its reserves of oil are a commodity the world wants regardless of the political climate in Tehran. But Iran’s ability to influence events in the Middle East could be greatly circumscribed should it step outside the parameters of the NPT.

Will any of this require extended US military engagement against Iran?

As of this writing, nobody really knows.

Public Law 93-148, 87 Stat 555

Office Of Legal Counsel. Overview of the War Powers Resolution. 30 Oct. 1984, https://www.justice.gov/file/150581/dl.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. "Libya bombings of 1986". Encyclopedia Britannica, 8 Apr. 2025, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Libya-bombings-of-1986. Accessed 22 June 2025.

Public Law 107-40, 115 Stat 224

Bradley, Curtis A. and Goldsmith, Jack L., "Obama’s Aumf Legacy" (2016). Articles. 10209.

https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles/10209

United States v. Irvine, 511 U.S. 224 (1994)

IAEA Board Of Governors. Verification and Monitoring in the Islamic Republic of Iran in Light of United Nations Security Council Resolution 2231 (2015). 31 May 2025, https://www.iaea.org/sites/default/files/25/06/gov2025-24.pdf.

Humphries, R. Fact Sheet: Uranium Enrichment: For Peace or for Weapons | Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation. 4 July 2021, https://armscontrolcenter.org/uranium-enrichment-for-peace-or-for-weapons/.

IAEA Board of Governors. NPT Safeguards Agreement with the Islamic Republic of Iran. 31 May 2025, https://www.iaea.org/sites/default/files/25/06/gov2025-25.pdf.

Mapstone, James, and Stephen Brett. “Radiological weapons: what type of threat?.” Critical care (London, England) vol. 9,3 (2005): 223-5. doi:10.1186/cc3061

Excellent job of assessing the situation, while not going off in any speculative direction. Peter, you are just the best at this, and thank you for answering all of my questions in advance!

Reading history, I’ve often thought that the hardest part of being a leader of a country is that you have to place bets on unknowns. Will taking Action X result in a better or worse outcome than doing nothing, or of taking a different action? It’s a calculated bet, and only time shows if you made the right call. Trump is either going to get his face carved into Mount Rushmore (as he has indicated he’d like), or he is going to be vilified by even many of his staunch supporters. Meanwhile, millions of lives could hang in the balance. Hey, all you college kids majoring in gender studies, would you like to experience the joys of boot camp? Adventure awaits, kids!

Your talent is a joy to your readers, Peter - keep it coming!

This helps a lot!