The BLS Employment Situation Summary Is Just BS

Once Again, The Numbers Do Not Make Sense

There is an implicit caveat we must remember when looking at any data set, and in government-sponsored data in particular: The data could be completely wrong.

Bear that in mind when reading the February Employment Situation Summary from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The headline numbers once again sound good—but there is an excellent chance those numbers are completely wrong.

Total nonfarm payroll employment rose by 275,000 in February, and the unemployment rate increased to 3.9 percent, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today. Job gains occurred in health care, in government, in food services and drinking places, in social assistance, and in transportation and warehousing.

On the surface, a seasonally adjusted increase to non-farm payroll employment of 275,000 is pretty good news. That number is well above what Wall Street economists were expecting.

Nonfarm payrolls increased by 275,000 for the month while the jobless rate moved higher to 3.9%, the Labor Department’s Bureau of Labor Statistics reported Friday. Economists surveyed by Dow Jones had been looking for payroll growth of 198,000.

Corporate media, for its part, was happy to play along with the narrative that the jobs report was good news.

If the economy is slowing down, nobody told the labor market.

Employers added 275,000 jobs in February, the Labor Department reported Friday, in another month that exceeded expectations even as the unemployment rate rose.

It was the third straight month of gains above 200,000, and the 38th consecutive month of growth — fresh evidence that four years after going into pandemic shutdowns, America’s jobs engine still has plenty of steam.

Perhaps the most skeptical corporate media take on the Employment Situation Summary came via Bloomberg:

As Mohamed El-Erian said on Surveillance, he felt "paralyzed" when looking at the numbers.

“People will see in this report what they want to see,” said El-Erian, the president of Queens College, Cambridge, and a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. Investors “will interpret this as good news, so you’re going to have even a bigger separation between economists who tell you things are uncertain and the market who sees things as all positive.”

Of course, the only way one can see only what one wants to see is if one accepts all numbers at face value—an assumption longtime readers will know should be rejected categorically. Peel back the numbers and we see an employment picture far less rosy than the corporate media narrative promotes.

Ironically, Wall Street looked at the BLS jobs report and was unimpressed. After surging initially on the report’s release, equities spent most of Friday in decline, with all the major indices losing ground on the day.

Bond yields were a bit more muddled, with the longer end of the yield curve rising and the shorter end of the curve falling on the day.

Wall Street looked at the jobs numbers and decided they were not as great as the government “experts” wanted everyone to believe. In fact, the jobs numbers are far more likely to be bad than good, at least in Wall Street’s eyes.

One reason for Wall Street’s pessimism is very likely a sense that the jobs numbers are going to work to delay future Federal Reserve cuts to the federal funds rate.

Federal Reserve policymakers weighing when to start interest-rate cuts got fresh reasons on Friday to remain on standby, after a government report showed robust job growth in February but also signs of labor market cooling that could help the Fed's battle with inflation.

U.S. employers added 275,000 jobs last month, a Labor Department report showed on Friday, handily beating the 200,000 that economists expected.

Wall Street really wants the Fed to trim rates, and the Fed really does not know if it wants to trim them or not—so the Fed is all too eager to jump on this or that data point to kick that particular can down the road as many times as possible.

The data may not be enough for the Federal Reserve, which is looking for inflation and the economy to slow, to begin its rate-cutting cycle, which would also come heading into the 2024 presidential election.

Earlier this week, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell reiterated that stance during his annual testimony before Congress.

"The committee does not expect that it will be appropriate to reduce the target range until it has gained greater confidence that inflation is moving sustainably toward 2%," he said in remarks prepared for testimony before the House Financial Services Committee.

Of course, if one takes the jobs numbers at face value, and interprets them as a sign that the economy is robust and strong, then one also has to conclude the results of the jobs growth for February could mean inflation is not “moving sustainably towards 2%”. If inflation heats up, this report will almost certainly mean the rate cut can has been kicked down the road as far as possible—and Wall Street would view that as “bad news” indeed.

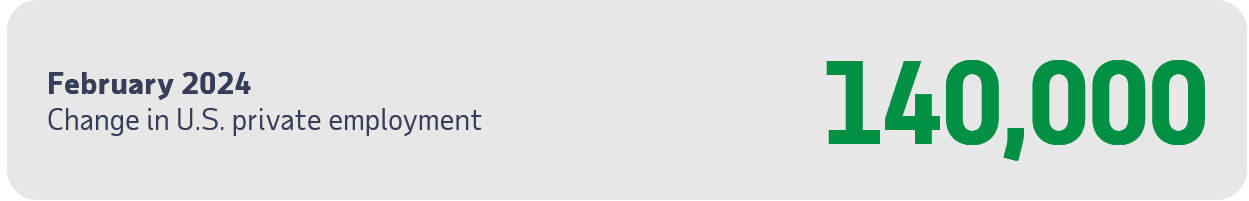

One huge reason to question the BLS jobs report: ADP’s National Employment Report reported jobs growth of only half of what the BLS reported.

Private sector employment increased by 140,000 jobs in February and annual pay was up 5.1 percent year-over-year, according to the February ADP® National Employment ReportTM produced by the ADP Research Institute® in collaboration with the Stanford Digital Economy Lab (“Stanford Lab”). The ADP National Employment Report is an independent measure and high-frequency view of the private-sector labor market based on actual, anonymized payroll data of more than 25 million U.S. employees.

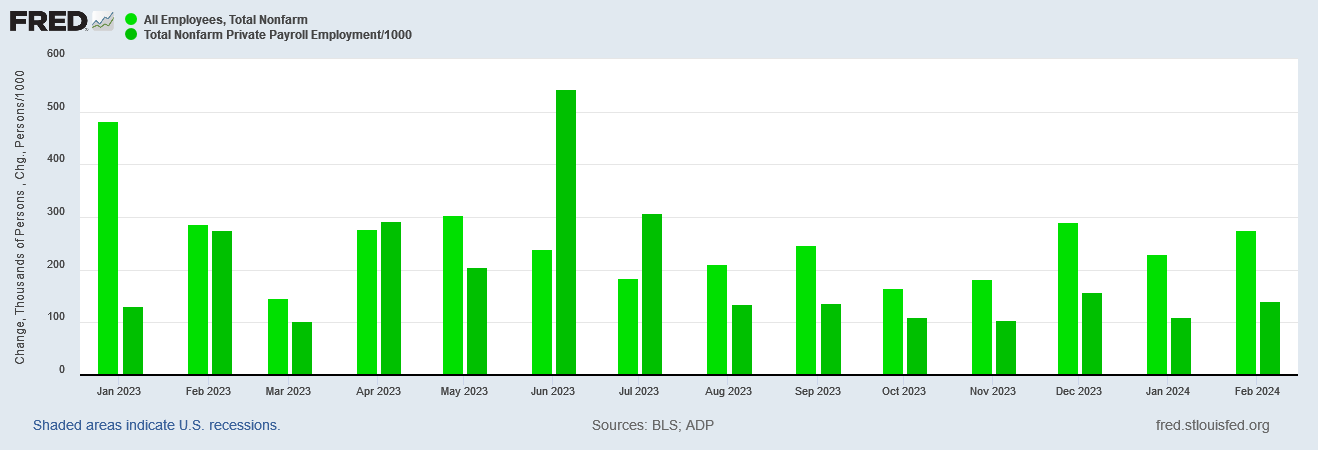

The ADP National Employment Report has been printing well below the BLS revisions since late last summer, and the monthly variance is increasing.

When two reports vary from each other to this extent, it is certain that at least one of them is inaccurate, if not both of them. Put another way, it is not possible for the ADP numbers and the BLS numbers to both be correct. One of them is definitely putting forth bad data!

Another reason to doubt the BLS numbers: Once again, the BLS has revised the prior months significantly downward.

December’s jobs data overstated the number of workers by roughly 45,000 workers, and January’s jobs data overstated the number of workers in the US economy by a staggering 124,000 jobs.

In just those two months, the BLS overstated job growth by nearly 170,000 jobs.

How much did the BLS overstate job growth in February? Tune in for the March numbers to find out.

That the BLS very likely overstated the numbers gets some confirmation from the fact that the number of potential workers not in the labor force increased from January to February.

That chance for overstatement increases even more when we consider that reported unemployment levels have been rising in this country since late spring

Unemployment is increasing, the number of workers not in the labor force is increasing, but the economy still created some 75,000 jobs more than expected?

Of course that sounds reasonable! (Don’t slip on the dripping sarcasm)

Yet even if the data was not subject to challenge for reasons of (in)accuracy, we would still be faced with internal contradictions. Some of the data just does not make sense.

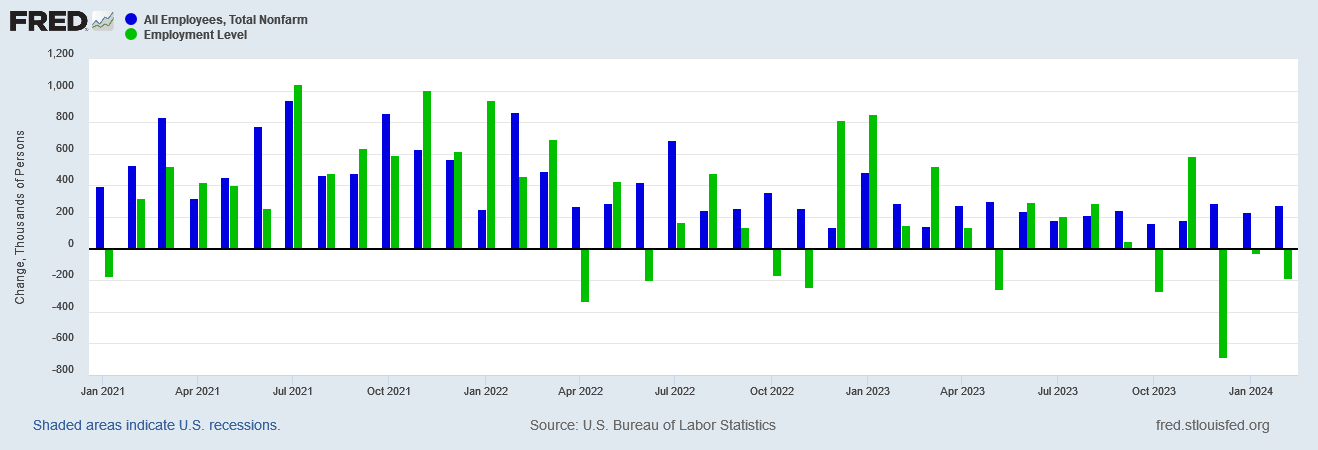

The 275,000 jobs comes from the Establishment side of the BLS Employment Situation Summary. Yet the Household Survey—part of the same jobs report—shows a seasonally adjusted 184,000 jobs lost.

Neither the corporate media nor the BLS spend much time and effort mentioning that rather grim statistic.

Nor can that variance be dismissed. It is mathematically impossible for there to be a net 275,000 jobs created in the same month where the overall employment level decreased by 184,000. A decrease in employment is job loss by definition, and if the data were completely reliable both the Establishment Survey and the Household Survey would show approximately the same level of job growth.

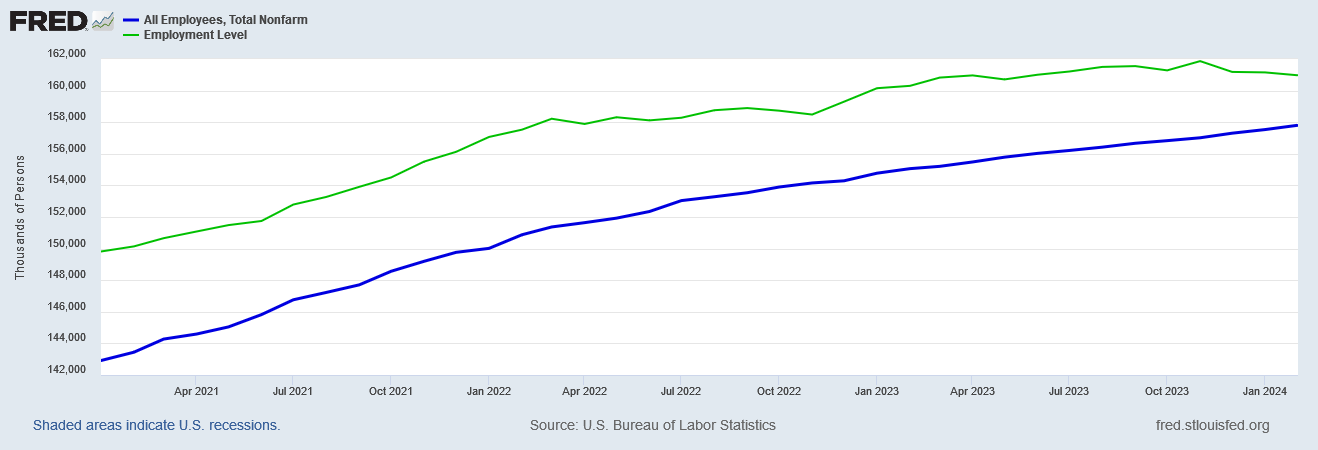

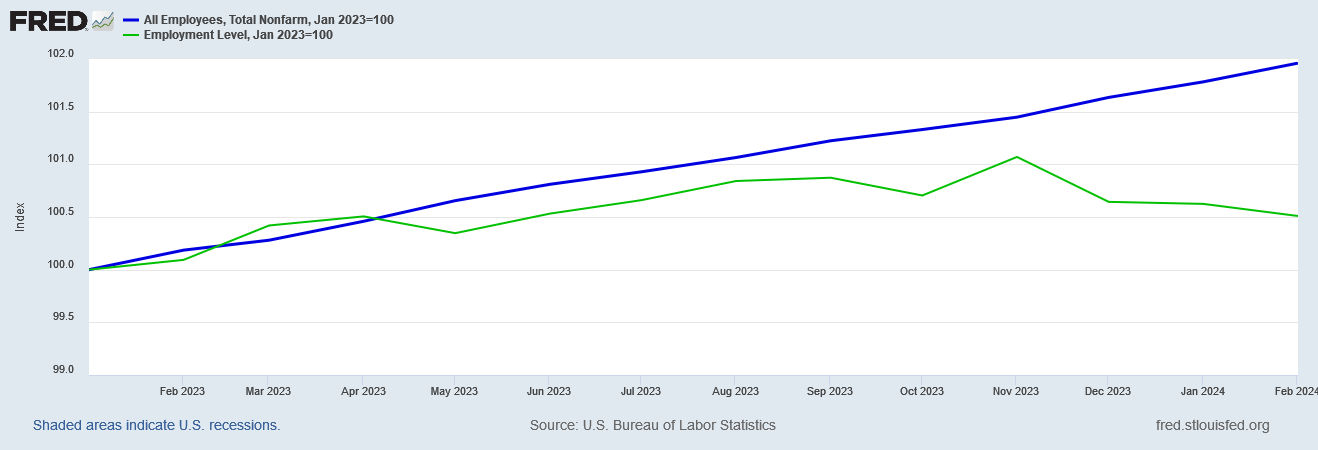

Moreover, the two surveys have for quite some time shown different trends in job growth.

The Household Survey charted a plateau in 2022 where job growth was essentially nil, and the Establishment Survey even after its many corrections and revisions has never identified the same slowdown in job growth. Yet that plateau, readers will recall, was confirmed in late 2022 by the Federal Reserve, when it reported that, by its calculations, total job growth in the second quarter of 2022 was a mere 10,500 jobs.

The April Employment Situation Summary claimed 428,000 jobs were added that month.

The May Employment Situation Summary claimed 390,000 jobs were created during the month.

The June Employment Situation Summary claimed 372,000 jobs were created during the month.

All told, the Bureau of Labor Statistics claimed 1,190,000 jobs were created during those three months.

Last week, the Philadelphia Federal Reserve shredded the narrative, stating that the actual number of jobs created during those three months was a whopping 10,500.

We know from past data the Establishment Survey has in at least that instance been the less reliable of the two surveys within the jobs report. If we impute that greater reliability to the Household Survey’s current data, the employment situation in the United States is far from strong. Even more disturbingly, the Household Survey data shows the employment situation in the United States has been not good for most of 2023, even after it showed job growth resuming after the 2022 plateau.

Indexed to the start of 2023, the Household Survey shows a weakening job growth trend which metastasized into a job loss trend in November, and has continued for the past three months. The Establishment Survey is blissfully unaware of any such downward trend in employment.

There is very likely a good reason for this: The Establishment Survey is based on a proportionally smaller sample set than the Household Survey.

While the response rates to both surveys have been declining over the years, as of January 2024, the Household Survey was still getting a 69.5% response rate.

The Establishment Survey, on the other hand, gets maybe two thirds of that response rate—43.3% as of December 2023.

With fewer responses and a far lower response rate, the Establishment Survey is always going to be less accurate and less reliable than the Household Survey. That much is basic statistics.

The BLS is obviously aware of the response rates, as they publish that data as well. However, they are not taking the obvious next step of de-emphasizing the Establishment Survey All Employees jobs count in favor of the Household Survey Employment Level—effectively swapping a less reliable metric for a more reliable one.

The irony, of course, is that the BLS freely uses the Household Survey to establish how many are unemployed during a particular month. The Household Survey data also has the benefit of internal consistency: The Employment Level and the Unemployment Level add up to the Labor Force, and the Labor Force and Not In Labor Force metrics add up to the non-institutional population level.

While the breakdown of employment by sector within the Establishment Survey is internally consistent, there is no metric to offer a “sanity check” on the Total Nonfarm Payroll metric itself. If that metric is off, then the entire Establishment Survey is no longer reliable—and we have reason just from the 2022 employment plateau confirmed by the Federal Reserve to question the reliability of the Establishment Survey.

Even corporate media is notionally aware of the response rate data and trends for both the Establishment Survey and the Household Survey. Bloomberg reported on the declining response rates this time last year.

No harm will likely come from you declining to rate your dining experience or refusing to take part in an opinion poll. Where survey fatigue may pose a real threat is in government statistics that everyone from policymakers at the Federal Reserve to traders on Wall Street to C-suite executives rely on.

The pandemic has accelerated what’s been a yearslong decline in response rates for many of the surveys US government agencies use to compile economic data—a worrying development in an age when markets can swing wildly on a jobs number that’s just a few thousand figures higher or lower than expected.

Corporate media last year even conceded the BLS survey data was becoming unreliable, yet it continues to present the that data uncritically, without exploring whether or not the data is reflective of the real world (spoiler alert: it isn’t).

The end result has been a Bureau of Labor Statistics at liberty to engage in Lou Costello Labor Math with wild abandon. The data does not let us know whether the BLS’ mendacity is the product of bureaucratic laziness or political pressures from the White House (or both). We cannot, from the data, differentiate between stupidity on the one hand and malice on the other.

We do not need to differentiate between stupidity on the one hand an malice on the other. We only need look at the data and disregard the narrative. We only need to evaluate the data for ourselves, and compare it against our experiences of the real world to see whether or not the data aligns with those experiences. We only need to recognize that the BLS, like all government bureaucracies, is frequently wrong.

When it comes to the Employment Situation Summary, the headline numbers the BLS puts out for public consumption are simply not to be trusted. When they choose the least reliable data to make their most sweeping assessments, it’s a fair bet they are not using trustworthy data nor are they handling that data in a trustworthy fashion.

As with all government statistics, the guiding principle in assessing the Employment Situation Summary should always be “Trust nothing. Verify everything.”

I believe absolutely nothing from the government anymore. WhenI was a kid, people in America would make jokes about the propaganda coming out of the USSR - made up news, bogus data, manipulated statistics, etc. It pains me to see how my own government’s official information has become little more than the nonsense in Russia’s newspaper “Pravda”. We seem to be just one step behind China now. Dystopian and depressing.

It’s a good thing there are still places like Substack, and honest writers like Peter. Thanks!