The Covid Vaccine Trials Tell Us More Than Just How Good They Are

All Three Big Pharma Vaccine Trials Suggest COVID Case Numbers Have Been Greatly Exaggerated

As countries around the world double down on COVID-19 vaccine mandates, passports, and other controversial (and potentially illegal) impositions on their respective populations, it is long past time to revisit the COVID-19 vaccines themselves, and the initial trial data provided to justify their use under various Emergency Use Authorization protocols both in the United States and Europe.

In particular, it is important to understand how much actual protection is being provided by the vaccines themselves. When we look at the trial data, we see that, even if the vaccines are as effective as claimed, their practical benefit is muted for one simple reason: none of the vaccine trials encountered much in the way of actual disease.

Pfizer: The Trial Where No One Got Sick

How can a vaccine be both effective and provide little protection? If very few individuals get sick with the virus, the relative health impact of the vaccine is going to be greatly reduced. If the Pfizer data submitted to win an EUA from the Food and Drug Administration is any guide, hardly anyone in their trial became ill, even among the placebo group.

The Pfizer clinical trial ran from July 27, 2020, through November 15, 2020, and covered some 43,548 persons, of which 36,523 successfully completed the trial.

Pfizer reported a stellar 95% efficacy rate from the trial, as the number of persons infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus in the vaccine candidate group was a 95% reduction over the number infected in the placebo group.

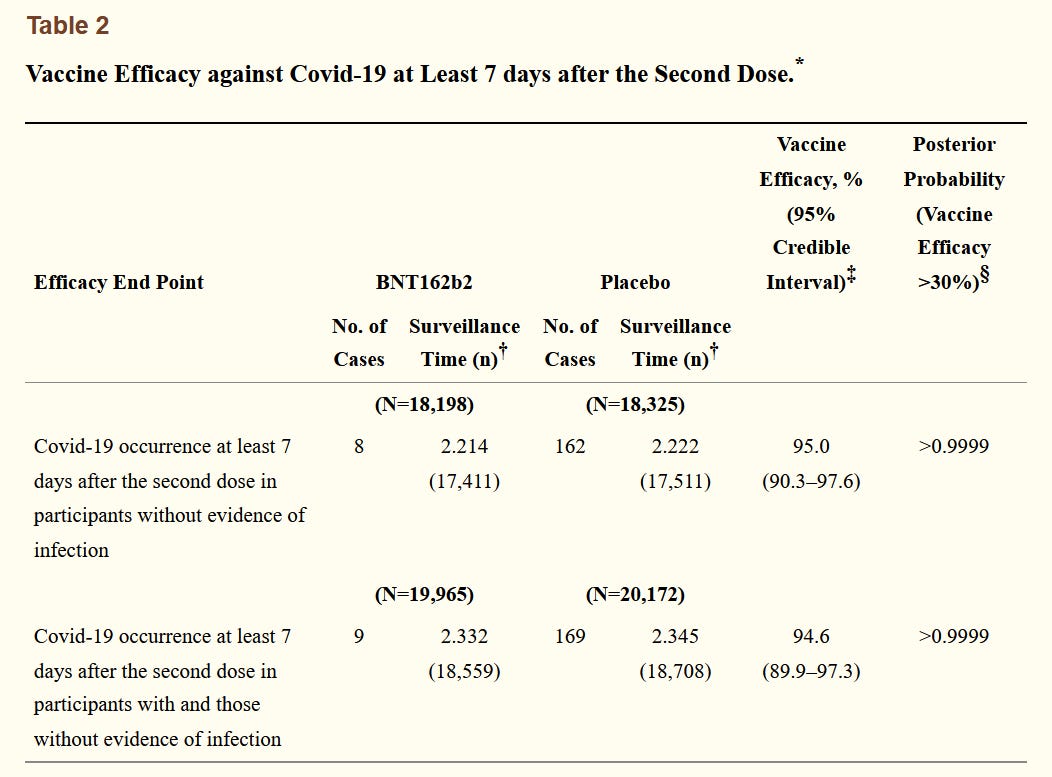

However, a total of 180 people tested positive for the virus (serology testing was used): 8 in the vaccine candidate group after receiving both doses of the vaccine, 162 in the placebo group after two shots, and ten cases that fell between the doses.

Focusing just on the cases after both doses were administered, we have a total 170 cases out of a total patient population of 36,523:

In relative terms, the Pfizer vaccine reduced the probability of infection from 0.88% to 0.04%

While the reduction from a 0.88% probability of infection to a 0.04% probability is indeed a dramatic reduction, relatively speaking, one is reminded of the old joke about having a penny and acquiring another penny: yes, you have doubled your money but you still only have two cents.

Is a 0.88% probability of infection a significant risk? That seems an unlikely assessment to make. Keep in mind, this is not mortality risk, but simply infection risk.

Moderna and Johnson & Johnson Show Similar Low Infection Rates

Both of the other vaccines in wide use within the United States show a similar phenomenon: overall, participants in the clinical trials did not get infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Moderna’s trial had a slightly higher infection rate in both groups:

The Johnson and Johnson vaccine had the highest infection rates:

However, at 1.5% of the placebo group becoming infected, even the Johnson & Johnson vaccine trial does not show a terribly high risk of infection. As with Pfizer’s data, the J&J trial data suggests there just is not a lot of infection risk with or without a vaccine. That greatly limits the practical utility of a vaccine.

Why The Low Infection Rates?

While the low infection numbers do not alter the mathematics of the claims made about the vaccines themselves, they do present another challenge: The infection rates are dramatically lower than the broadly reported test positivity rates for the time frames covered by the trials themselves.

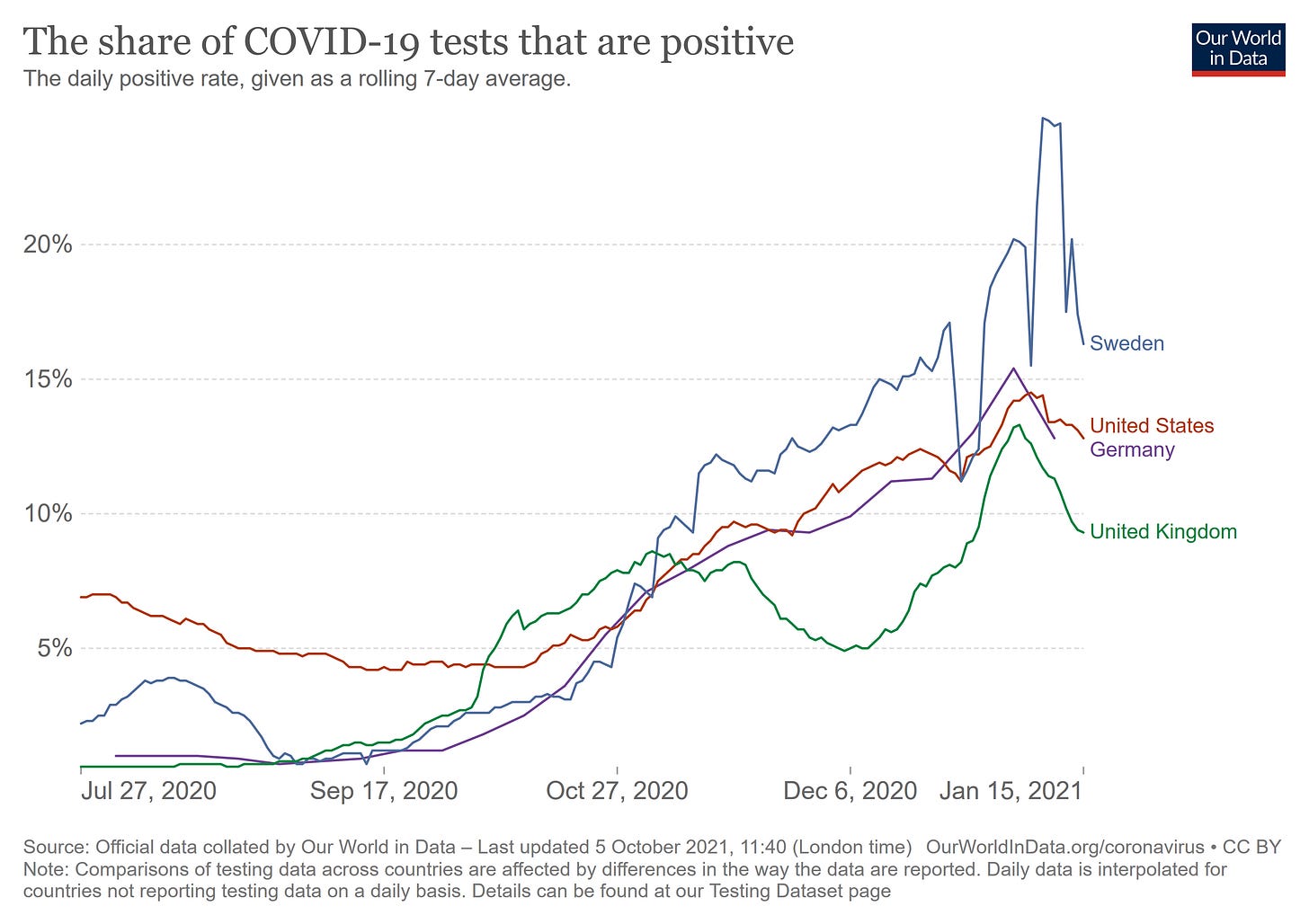

During the period of the Pfizer trial, for example, the test positivity rate in the United States rose well above 5%, a phenomenon that was echoed in both Germany and Sweden and, to a lesser extent, in the United Kingdom.

Even without challenging Pfizer’s efficacy claim, the question about the discrepancy in infection rates between their clinical trial and the broader experience of several countries remains unanswered.

If the infection rates are in fact less than 1%, which is what the Pfizer study suggests, then the test positivity rates that are being widely reported are also being widely overstated—by as much as an entire order of magnitude at least.

PCR Tests: Reliable Or Not So Much?

One possibility for the discrepancy is that we are seeing an inherent inaccuracy in the Real Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) tests commonly used in testing for SARS-CoV-2. Since the beginning of the pandemic, there has been a segment of the medical community that has voiced concern about the accuracy of these tests, even as they remain the putative “gold standard” for testing.

Concerns have been raised over the last several months that laboratory tests widely deployed to detect SARS-Cov-2 — what are known as polymerase chain reaction, or PCR, tests — may in fact be picking up remnants of the virus instead of meaningful levels of infection. Some critics have argued that significant numbers of purportedly positive COVID-19 tests are actually not infectious at all.

The accuracy question revolves around the number of replication cycles needed to detect a virus. In PCR technology, a viral sample is replicated multiple times, with each cycle of replication doubling the amount of genetic material from the previous cycle. The more cycles that are needed, the lower the amount of virus present in the initial sample.

At the center of the debate is the "cycle threshold" at which a PCR test operates. PCR tests work by multiplying a virus fragment over a series of cycles until it can reliably detect and confirm the virus within a sample. The more cycles a test must go through before it detects the virus, the smaller and weaker the original sample was.

High cycles, in other words, are expected to correlate to weaker viral samples, indicating that a patient's "positive" case in that context may be more or less meaningless from an epidemiological or virological perspective.

There is significant dispute about whether more than 30-35 replication cycles shows actual viral infection, or merely “dead nucleotides”—viral fragments left over from either a prior (and cleared) infection or simple exposure that never developed into full blown infection.

Even Anthony Fauci, the government’s leading spokesperson on all things COVID, has acknowledged the debate over the accuracy and relevance of tests with high cycle thresholds:

Joining the hosts of This Week in Virology in July, Fauci directly responded to a question about COVID-19 testing, specifically how patients with positive tests might determine whether or not they are actually infectious and need to quarantine.

"What is now sort of evolving into a bit of a standard," Fauci said, is that "if you get a cycle threshold of 35 or more ... the chances of it being replication-confident are minuscule."

"It's very frustrating for the patients as well as for the physicians," he continued, when "somebody comes in, and they repeat their PCR, and it's like [a] 37 cycle threshold, but you almost never can culture virus from a 37 threshold cycle."

"So, I think if somebody does come in with 37, 38, even 36, you got to say, you know, it's just dead nucleotides, period."

Yet, despite a certain consensus that high replication cycles lead to high false positives, many of the PCR tests deployed throughout the United States at least have had from the beginning very high cycle thresholds. Moreover, the potential for false positives from these tests was noted in the New York Times back in August of 2020.

The PCR test amplifies genetic matter from the virus in cycles; the fewer cycles required, the greater the amount of virus, or viral load, in the sample. The greater the viral load, the more likely the patient is to be contagious.

This number of amplification cycles needed to find the virus, called the cycle threshold, is never included in the results sent to doctors and coronavirus patients, although it could tell them how infectious the patients are.

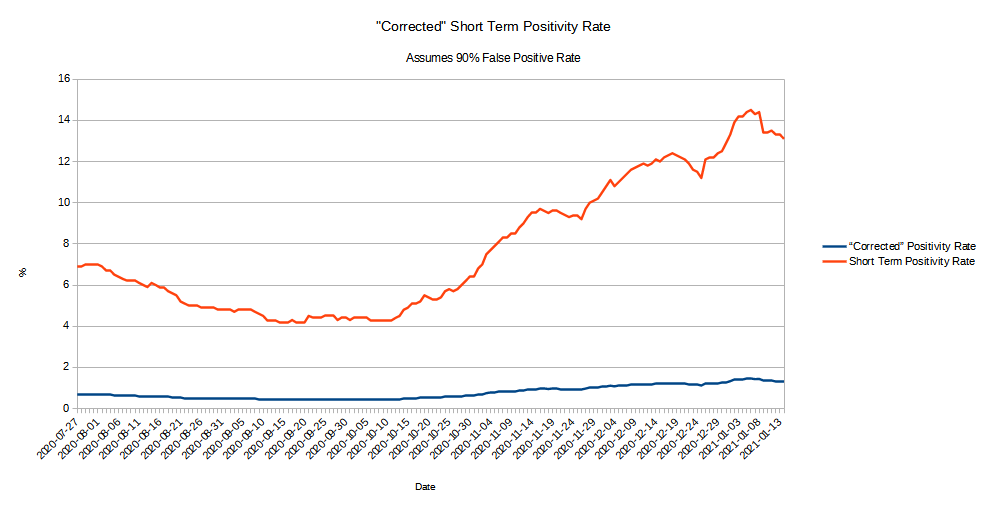

In three sets of testing data that include cycle thresholds, compiled by officials in Massachusetts, New York and Nevada, up to 90 percent of people testing positive carried barely any virus, a review by The Times found.

A 90% discrepancy between the reported positivity and the “corrected” positivity when false positives are excluded is no small shift in the data. If we take the positivity trend reported across the United States during the time frame of the Pfizer clinical trial and reduce it by 90%, the picture of the pandemic thus painted is radically different:

It bears noting that the “corrected” rate matches the infection rates recorded in all three of the vaccine candidate trials.

Not Just Missing Cases, But Making Up Cases

As I have argued previously, a key defect in the narrative arc of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has been a conspicuous lack of cases to match the predictions made. As far back as February of 2020, the reported data simply did not match the apocalyptic narrative that was taking hold, and as late as September of 2020, that discrepancy remained, as state after state failed to show the dramatic hospitalization rates that were being claimed:

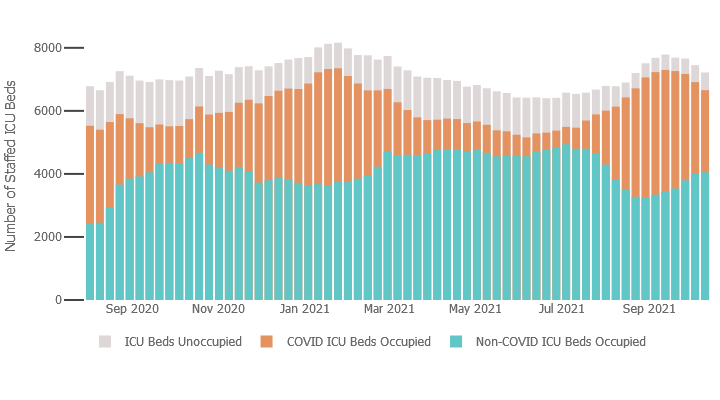

Even if we do not call into question the test results themselves (test accuracy is always a question but falls outside the scope of this particular analysis), we still must address the fact that these positive test cases do not appear to require hospitalization.

Are these "asymptomatic" patients? Are they simply getting mild cases of the disease that require little more than bed rest and fluids, much the way ordinary influenza like illness is managed?

If these students who test positive are not sick or not all that sick, and if they are not winding up in hospital, how is it that school officials conclude there is major risk either to keeping them on campus or sending them home?

While Pfizer’s vaccine candidate trial, along with that of Moderna and Johnson & Johnson, do show at least initial efficacy for their respective inoculations, they also show that, not only is the narrative missing the case data necessary to substantiate it, but that much of the case data may actually be made up. The reason so many states were not (and are not) seeing an actual overflow of patients may very well be that patients are either not sick/symptomatic or have only extremely mild symptoms that do not require hospitalization or even a trip to the doctor; and it is certain that the data does not support a claim of patients maxing out hospital capacities. A quick glance at ICU capacity and utilization rates in Texas, New York, and Vermont shows that, overall, hospitals in these states are absorbing patient loads:

Texas:

New York:

Vermont:

COVID Is Real, But It Is Not The Black Plague

None of this suggests, nor should be taken to imply, that the SARS-CoV-2 virus is a “hoax” or that the COVID-19 disease is not very real. Infectious respiratory viruses, of which SARS-CoV-2 is but one, are a real health issue, one that historically claims tens of thousands of lives in the United States each year. The 2018-2019 influenza season alone claimed over 50,000 lives just in the United States:

The SARS-CoV-2 virus arguably has been more severe than seasonal influenza, particularly for the most severely affected patient demographics—but the degree of severity changes dramatically if we are looking at a 90% false positive rate on diagnostic testings. If the tests are overstated with 90% false positives, then the recently bemoaned 700,000 deaths from the SARS-CoV-2 virus becomes 70,000—still high, but much more inline with a typical influenza season.

Perversely, the COVID vaccine trial data suggests that, regardless of what the media has claimed about the danger of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, the actual dangers are considerably less, bordering on the normal. Despite experts warning of an upcoming “twindemic” as we enter the 2021-2022 flu season, the actual threat of COVID-19 at least may be grossly exaggerated. While the Big Pharma inoculations do legitimately claim some benefit based on the raw mathematics, the practical utility of that benefit is limited by the conspicuous lack of disease within their trials.

COVID-19 is a real disease, but the Black Plague it is not. And never has been.

Excellent, excellent, excellent article, Peter!

The discrepancy between the study case rate and the real world "PCR case rate" is revealing, just as the lack of deaths or hosp. in the study is revealing.

And their decision to kill (maybe literally!) their control group by injecting the placebo group.