The Faucist's Dilemma: Politically Correct Disease Names

Why Monkeypox Should Not Be Called Monkeypox. Seriously.

There are times when it is difficult to take the Faucists seriously. Then there are times when it is impossible to take the Faucists seriously. This is one of those impossible times.

Yet the Faucists are indeed serious—not serious scientists, or serious doctors, or even serious people, just “serious” (insert favorite “serious” meme here).

What are the Faucists “serious” about this time? The crucial, even urgent need to rename monkeypox to anything other than monkeypox. Because stigmas. Seriously.

The prevailing perception in the international media and scientific literature is that MPXV is endemic in people in some African countries. However, it is well established that nearly all MPXV outbreaks in Africa prior to the 2022 outbreak, have been the result of spillover from animals to humans and only rarely have there been reports of sustained human-to-human transmissions. In the context of the current global outbreak, continued reference to, and nomenclature of this virus being African is not only inaccurate but is also discriminatory and stigmatizing. The most obvious manifestation of this is the use of photos of African patients to depict the pox lesions in mainstream media in the global north. Recently, Foreign Press Association, Africa issued a statement urging the global media to stop using images of African people to highlight the outbreak in Europe

You have to give the authors credit: that’s a lot of virtue-signalling to pack into a single paragraph. Of course, it might be slightly wide of accurate in its core assertion, that the media thinks that everyone in West Africa has monkeypox.

A random DuckDuckGo search using the phrase “monkeypox is endemic” found this item in the Khaleej Times (a UAE publication) on how travelers from the UAE to Africa can protect themselves:

Travellers can protect themselves by:

— Avoiding contact with infected animals (dead and living)

— Refraining from eating or touching wild animals

— Washing hands with soap and water or an alcohol-based disinfectant

Shouldn’t media misreporting about how monkeypox is “endemic in people” include saftey recommendations that involve…well…people?

Following a link in that article led to this article about Dubai’s isolation protocols.

The Dubai Health Authority (DHA) has issued isolation guidelines for confirmed monkeypox cases. Taking to Twitter, the authority shared a guide on the zoonotic viral disease that details all the relevant procedures.

By definition, a disease that is described as “zoonotic” cannot be “endemic in people.”

Still, that is just one publication. Perhaps the authors were thinking of the New York Times’ reputation for biased journalism? Let’s look at one of their early articles on the outbreak.

How infectious is it?

Typically it does not lead to major outbreaks — in most years there are just a handful of cases outside Africa, if any. The most severe outbreak in the United States came in 2003, when dozens of cases were linked to exposure to infected prairie dogs and other pets. It was the first time there had been a monkeypox outbreak outside of Africa, according to the World Health Organization.

Within Africa, 11 countries have reported cases since 1970, when the first human case was identified in a 9-year-old boy in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Nigeria has experienced a large outbreak, with more than 500 suspected cases and 200 confirmed cases since 2017, the W.H.O. said.

Maybe I’m being overly cynical (yes, that does happen!), but I’m not sure 500 cases over 5 years qualifies monkeypox as “endemic in people” in West Africa. Monkeypox is (or, rather, has been) clearly endemic in West Africa, by simple virtue of the fact that, until recently, that was where all the cases arose. That makes the disease endemic to that part of the world by definition. However, the assertion that the media is presenting monkeypox as a disease common among West Africans seems a rather extreme reading of the texts.

Missing Their Own Point

Amazingly, the authors of that missive about the “urgent need” to rename monkeypox presented some intriguing facts—and then completely ignored their significance.

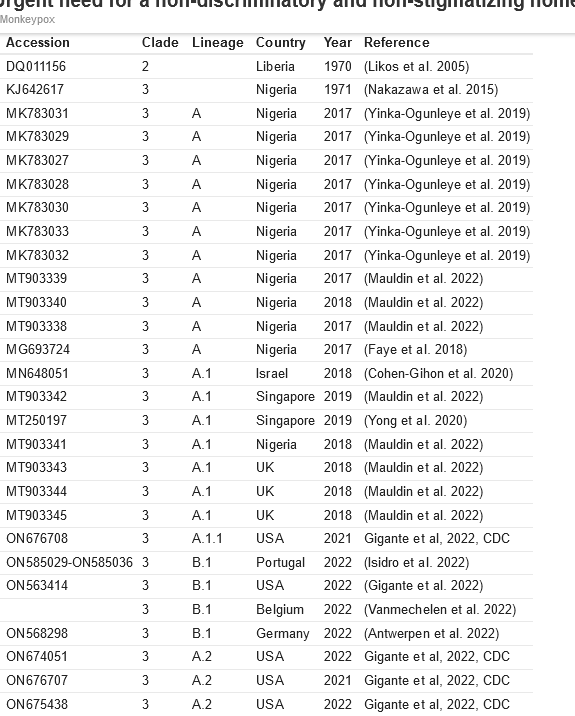

In describing their proposed taxonomic naming conventions for monkeypox, they presented the following list of monkeypox genomes:

Note that many of the listed genomes are not tied to Africa. The ones from 2018 and 2019 appear to be previously known cases of “exported” monkeypox infection from Nigeria, but the genomes from 2021 onward are not. This proliferation of genomes outside of Africa further strengthens the notion that monkeypox is no longer endemic just in West and Central Africa, but is spreading.

That the virus is no longer endemic to just Africa is significant because of another data point presented by the authors: the strain of monkeypox involved in the current “non endemic” outbreak is not “zoonotic”, but spreads person to person.

We also suggest naming a new clade, containing genomes sampled between 2017–2019 from the UK, Israel, Nigeria, USA, and Singapore and genomes from 2022 global outbreaks (Figure 1B). Since viruses in this clade have been transmitting from person to person in dozens of countries and potentially over multiple years, we propose that this represents transmission route distinct from that of previous MPXV cases in humans and should be afforded a distinct name so that it can be referred to specifically in both scientific discourse and the general media.

This description is distinctly at odds with the WHO depiction of monkeypox as a zoonosis. It also stands in stark contrast to the CDC’s depiction of monkeypox transmission. Yet the authors are too worried about “stigmatizing” folks in West Africa to explore these variances. A valuable line of inquiry is being effectively discarded.

The Global Outbreak IS Misreported

The sad irony here is that the corporate media has misreported the global monkeypox virus.

There are crucial differences between the current global monkeypox outbreak and traditional monkeypox cases. That much is undeniable, as is the media’s total failure to appreciate those differences.

Yet rather than seizing the moment to constructively criticize corporate media reporting and medical research thus far on the disease, the authors of this published plea for political correctness have chosen to address an issue that, by any reasonable reading of the corporate media reporting, simply does not exist. In true Faucist fashion, they are framing their science with their ideology, and eradicating their science as a direct consequence. As I have argued before, such scientific bastardy never ends well.

Rather than worrying about a politically correct name for the disease, the authors would accomplish far more by focusing on the relevance of the facts they themselves bring to the fore: the global outbreak of “non endemic” monkeypox is clearly not a zoonotic disease, and its global spread suggests monkeypox may be endemic in areas beyond West and Central Africa. These data points carry profound public health consequences for the entire world; arguably, they mark monkeypox’ ascension to fully filling the pathogenic void left by its more infamous cousin smallpox, albeit without the mortality (so far).

In every scientific inquiry or endeavor, the facts and the data will always matter far more than the names, politically correct or otherwise. Monkeypox is no different.