While much of the inflation narrative of late has been focused on highly volatile and sharply rising food and energy prices, there is another inflation category that is wreaking as much or more havoc on consumers’ budgets as these headline grabbing areas: housing.

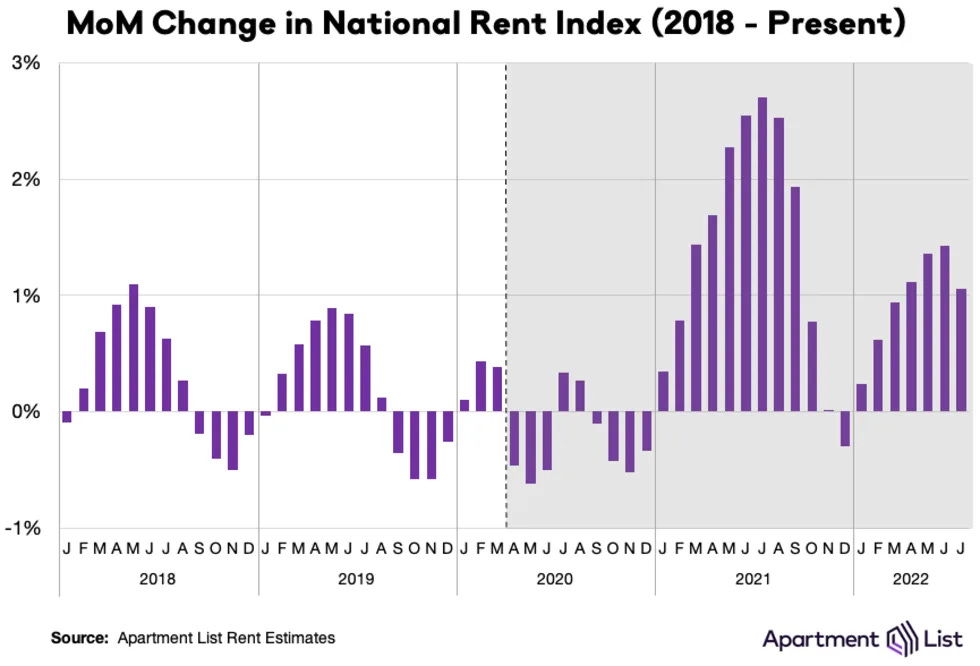

Not only are housing prices in the stratosphere, so too are rents, with several markets seeing record increases in apartment rental rates since the start of 2021. So dramatic have the rent hikes been that, as measured by The Apartment List’s National Rent Index, the July increase of 1.1% month-on-month represents a decline to less than half of the month-on-month increase of 2.9% in July, 2021.

Our national rent index increased by 1.1 percent month-over-month in July, representing a slight cooldown from last month’s 1.4 percent increase. In July 2021, our national rent index logged record-setting month-over-month growth of 2.7 percent, more than doubling this month’s increase. In contrast, from 2017 to 2019, month-over-month growth in July averaged 0.6 percent, just over half of this month’s increase. Over the past 12 months as a whole, rent prices have spiked by a staggering 12.3 percent nationally. That said, our year-over-year growth estimate has been gradually cooling in recent months after peaking at 18 percent last December, as monthly growth comes in slower than last year’s pace. This month’s slowing rate of growth is consistent with the timing of seasonal trends that we have observed in the past, and it is likely that growth will cool further in the coming months, as the fall and winter tend to bring a slowdown in rental market activity.

At 12.3% year-on-year, July’s rent inflation, although cooler than June’s figure, was still nearly 4 percentage points higher than headline consumer price inflation, having peaked at the end of 2021 at over 11% higher.

Rent inflation rivals only energy price inflation for the magnitude of distortion within the typical consumer’s budget.

Shelter Price Inflation Leads To Shelter Insecurity

Shelter, just like food, is a necessity of living. With many parts of the consumer price index, purchases of goods can often be postponed or even canceled to a large degree, or substitute goods can be found.

There are no substitutes for food and there are no substitutes for shelter. Everyone needs to eat and everyone needs a place to live. There is no getting around these basic realities.

As a consequence, when the prices of food rise, the ability of people to buy food—and therefore to buy enough food—diminishes. Food price inflation today becomes food insecurity tomorrow, with hunger coming the day after.

By the same token, shelter price inflation today becomes shelter insecurity tomorrow, with homelessness coming the day after.

There are numerous examples of this grim evolution throughout the media, and all following a broadly similar track: rising rents and compressed wages creates first stress over rent payments, then shelter insecurity as one falls behind in the rent, and finally homelessness, as the landlord pursues eviction to address non-payment of rent.

Even before she lost her job this past spring, things were tight for Nikki Cox. She worked as a service representative at an insurance company in North Carolina and had been making $20 an hour. Half of her income went to rent.

"If I did have something left over, it might be about a hundred [dollars], maybe," she says. But even that "would buy my groceries and my necessities."

It left Cox in trouble when her company's business dropped and her hours were cut. She took a temp job elsewhere, but that paid $15 an hour, a substantial hit on her income. The hours also conflicted with her other job, which she left because she figured she would be laid off soon.

Then in May she got COVID and had to stay out of the office for three weeks, unpaid. At one point, Cox says she relied on customer points at convenience stores to get free dinners. Her nephew also helped.

As inflation rises, the erosion of real income puts more people “on the bubble”, in a precarious position where any unforeseen calamity put them in danger of eviction and homelessness.

Jada Riley thought she had beaten homelessness.

The 26-year-old New Orleans resident was finally making a steady income cleaning houses during the pandemic to afford a $700-a-month, one-bedroom apartment. But she lost nearly all her clients after Hurricane Ida hit last year. Then she was fired from a grocery store job in February after taking time off to help a relative.

Two months behind on rent, she made the difficult decision last month to leave her apartment rather than risk an eviction judgment on her record. Now, she's living in her car with her 6-year-old son, sometimes spending nights at the apartments of friends or her son's father.

“I've slept outside for a whole year before. It's very depressing, I'm not going to lie,” said Riley, who often doesn't have enough money to buy gas or afford food every day.

With the ending of pandemic-era moratoriums on evictions, there has been a steep rise in evictions nationwide, as the combination of inflation and the ending of various COVID-related assistance programs stretches many budgets past the breaking point.

According to The Eviction Lab, several cities are running far above historic averages, with Minneapolis-St. Paul 91% higher in June, Las Vegas up 56%, Hartford, Connecticut, up 32%, and Jacksonville, Florida, up 17%. In Maricopa County, home to Phoenix, eviction filings in July were the highest in 13 years, officials said.

Some legal advocates said the sharp increase in housing prices due to inflation is partly to blame. Rental prices nationwide are up nearly 15% from a year ago and almost 25% from 2019, according to the real estate company Zillow. Rental vacancy rates, meanwhile, have declined to a 35-year low of 5.8%, according to the Census Bureau.

With rent and housing prices running well ahead of overall consumer price inflation, shelter is claiming more and more of a typical consumer’s monthly real income, which consumer price inflation is steadily making smaller and smaller.

Shelter price inflation is already causing shelter insecurity—and homelessness for many is not far off.

As With The Rest Of The Inflation Picture, The Supply Chain Is The Culprit

The primary driver of rent and housing price increases is fundamentally the same as it is for other portions of the CPI—inadequate supply. There simply are not enough homes, nor nearly enough apartments, to meet housing demand at current prices.

"We're seeing a shortage, or housing underproduction, in all corners of the U.S.," says Mike Kingsella, the CEO of Up for Growth, which on Thursday released a study about the problem. The nonprofit research group is made up of affordable housing and industry groups.

"America's fallen 3.8 million homes short of meeting housing needs," he says. "And that's both rental housing and ownership."

Even economists who disagree with the 3.8 million homes shortfall still agree that the existing supply of homes is far short of what is needed.

There is some debate about just how bad the shortage is in terms of the number of homes the U.S. needs. Mark Zandi, the chief economist of Moody's Analytics, estimates the shortfall is closer to 1.6 million homes. He was not a part of this study.

"It's very difficult to know precisely what the shortage is," Zandi says. "But the bottom line is, no matter what the estimate is, it's a lot of homes that we're undersupplied." And he adds there's no doubt that many more homes need to be built to ensure that housing becomes more affordable, whether it's rental housing or homeownership.

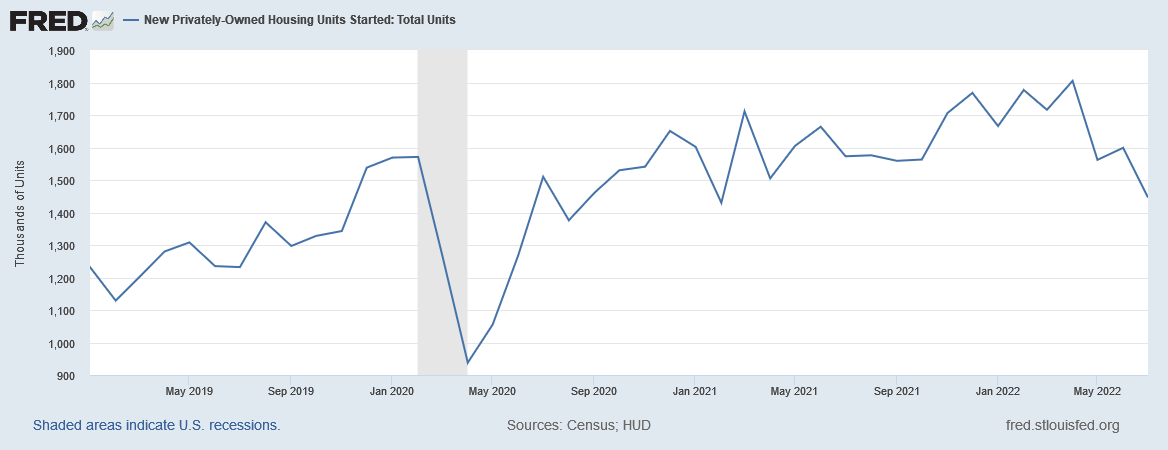

Perversely, as inflation and interest rate hikes make home purchases increasingly unaffordable for many individuals, housing starts in this country are declining.

Far from increased prices drawing in fresh supply to help moderate and eventually reduce prices, the exact opposite is happening.

In part this is due to a downward trend in home sales: with fewer homes coming off the market developers have less incentive to begin new construction.

Home sales follow a volume cycle rather than a price cycle, and this phenomenon is exaggerated for new homes. When demand dries up, developers prefer to delay projects and wait out the downturn. Homes that developers do sell during these periods are the ones for which they can still command a high price. Since few people are willing to pay the same price with higher interest rates, prices remain the same and sales go down.

The result is that home price inflation continues unabated even as housing sales drop precipitously.

Without more housing starts, without a greater supply of homes for sale to entice people out of renting and into home ownership—which in turn alleviates a shortfall of rental units, shelter price inflation overall is set to get worse over the near term, and the recent declines in rent inflation are likely to reverse and begin rising anew.

Shelter price inflation will drive more shelter insecurity, leading to more homelessness.

The ARM Time Bomb: The Ghost Of 2008

The Federal Reserve’s efforts to combat runaway inflation with rapid interest rate rises is setting the stage for a replay of the 2007-2010 mortgage default crisis, which when it happens will throw a number of homes into foreclosure and their occupants into the street.

Between Jay Powell’s jawboning of interest rates and the Federal Open Market Committee hiking interest rates in multiple 75bps increments, one important interest rate has more than kept pace: the interest rate on a 30-year mortgage, which is only slightly down from its highest rate in over a decade.

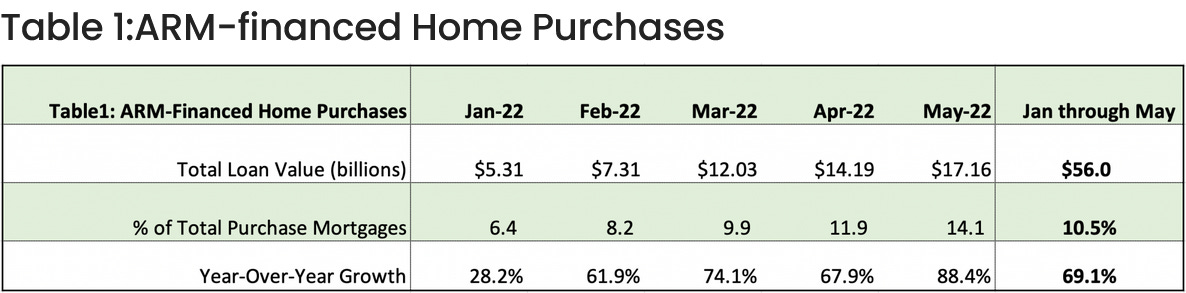

The increasing cost of the more stable 30-year fixed rate mortgage has incented prospective homebuyers to take out more volatile adjustible rate mortgages—which are themselves increasing, although they currently enjoy lower rates than the 30-year fixed rate mortgage.

Currently, home purchases using ARMs are at the highest level they’ve been in 8 years, comprising 10.5% of all home sales during the first five months of this year.

However, adjustable rate mortgages reset their interest rate every year after an initial period (frequently 5 years), which means homeowners with an ARM may find themselves paying considerably more on their mortgage down the road.

The ARM often makes sense financially if the homeowner is either able to refinance the mortgage later on or plans to sell the home before the initial period has elapsed.

Yet with home sales declining, home prices will eventually decline as well—which could inhibit plans to refinance or sell in the future, as homes purchased today may quite possibly have a market value in the future below their current price. If homeowners become trapped in an adjustable rate mortage past the initial period, their monthly mortgage payments may increase past what they can afford, thus triggering a wave of mortgage defaults, foreclosures—and thus, evictions—and, as a consequence, more people losing their homes.

While it may not have the extreme market consequences of the subprime mortgage crisis of 2007-2010, the current interest rate environment is inviting a replay of the same debt dynamics that precipitated that crisis.

Shelter price inflation today produces shelter insecurity tomorrow, with homelessness the day after.

The Calamity In Slow Motion

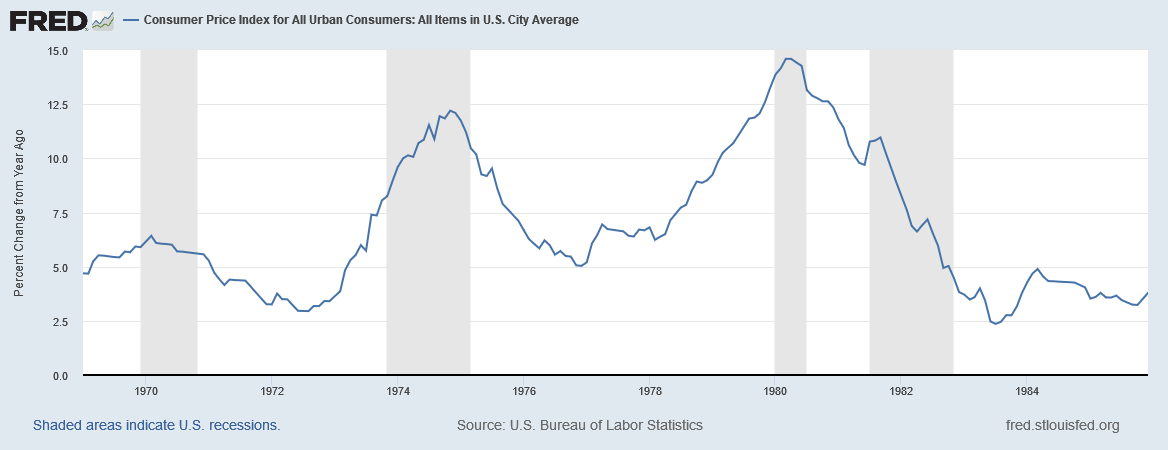

Inflation is not an immediate calamity. It unfolds over a period of months and sometimes years. The hyperinflation of the 1970s began in the summer of 1972 and did not fully resolve itself until the summer of 1983.

By the same token, today’s inflationary cycle which began in 2020 may take years to resolve itself. Barring a complete collapse in prices (which would likely signify an economic upheaval of quite a different nature), the inflation we are experiencing now is going to be with us for a number of years yet.

For however long inflation lingers in the economy, economic insecurities—food insecurity as well as shelter insecurity—are going to become increasingly prevalent and increasingly real for an increasing number of people.

In housing, inflation is a crisis that has only just begun. The storm is still gathering, and its climax has yet to arrive. Be assured, however, that the climax will arrive, and it will sweep away more than a few peoples’ homes when it does.

Waxing pedantic, but calling the inflation of the 1970s "hyperinflation" is hyperbole. ;)

Builders may choose not to build, but if mortgage interest rates get high enough, prices on existing homes will come down because people simply won't be able to afford the monthly payments at current prices. My neighbor across the street here is a real estate agent and his opinion is we're already starting to see this happen.