The Price of Trade War: Can China Afford to Pay?

Trump Lit The Fuse—China’s Economy Might Burn

Liberation Day was not merely an announcement of tariffs on most of the world.

Liberation Day was also President Trump’s declaration of a trade war with China.

Both in response to what President Trump deems to be China’s unfair trade practices as well as China’s role in America’s fentanyl crisis, Trump imposed what eventually amounted to a total tariff rate of 145% on products imported from China.

Corporate media and Wall Street have had a serious case of the vapors over the potential fallout from this trade war to the US economy, given the volume and variety of goods the US currently imports from China.

Yet how does this trade war impact China? How well can China hope to respond to the tariffs as well as Donald Trump’s usual bluster?

Last fall I wrote at some length regarding the steady deflation of China’s economy—a deflation that does not bode well for the Middle Kingdom if Trump’s trade war lasts for any significant length of time.

President Trump may have lit the trade war fuse, but it could very well be that it is China’s economy which will burn.

With tariff and trade war very much a current and almost certainly future reality for China, a review of China’s economic situation is very much in order.

Is China Ready For A Trade War?

Unsurprisingly, corporate media takes a dim view of President Trump’s tariffs, and an even dimmer view of his trade war with China, with several outlets going so far as to speculate that China is likely to prevail in the economic test of wills.

A recent op-ed piece in the Financial Times went to some length to detail why China would weather Trump’s tariff tantrum, arguing that the tariffs, the trade war, and President Trump’s economic policies were little more than the chaotic bumblings of a rank amateur.

The president’s team is scrambling to rationalise the chaos as a master plan to build a coalition to defeat Chinese mercantilism. But any such plan is doomed to fail. To understand why, we first need to get at what Trump really wants from tariffs. The usual claims — that he wants to crack down on unfair trade practices, eliminate trade deficits, reindustrialise America, confront China — do not hold up. Trump often invokes these goals. But these stated aims often contradict each other, are contradicted by other policies or are obviously unachievable.

We should note, however, that such pieces are pure propaganda, and in this instance pro-China propaganda. That is made plain by the sweeping generalizations the article makes about how the world views President Trump’s tariffs, as a sign that the US is an unreliable actor on the world stage and that Trump is isolated in his stance against China.

Most countries now understand that the various economic rationales offered by Trump’s advisers are just window-dressing. So long as Trump is in charge, the US is unreliable, and no sane leader will join him in a crusade against China.

Such claims are by their nature mere opinion on a good day, and jingoistic rhetoric on every other day.

Yet the author makes another claim in particular which warrants further scrutiny, regarding China’s ability to withstand trade sanctions from the United States.

China may be losing demand from the US, but this can be replaced by domestic consumer demand, which has been abnormally weak thanks to overly tight monetary policy, and an obsession with pouring state resources into manufacturing. Xi Jinping has reversed course and is now serious about boosting domestic demand.

This claim is questionable on its face, because if China has had the capacity all along to boost domestic demand, why has it only recently attempted to do so, as the author claims?

Does China’s own economic data support such a claim? It would take a generous reading of the economic data for that to be the case.

Remember, China has been mired in deflation for quite some time. Domestic demand is not something China has had in abundance, and we can see that by looking at their Consumer Price Index data.

While China’s CPI does fluctuate up and down, since 2023 it has done so largely in a range around 103. It is not appreciably rising or falling very far from that value, having risen to that value from mid-2021 through 2022.

Price levels and even inflation are occasioned by the demand for goods and services, and while much of the rhetoric of consumer price inflation revolves around variables such as the money supply and the relative scarcity of goods, the dynamic of a marketplace is invariably that prices rise when there is demand for goods which exceeds supply, and prices fall when the supply of goods exceeds the demand.

What a stable Consumer Price Index tells us is that there is not a significant un-tapped demand within China’s domestic market. If there were unmet needs and wants, we would see that in the CPI as a general rise in prices. Since 2023 we have not seen a rise in general prices.

With respect to core consumer goods and services, the presence of a falling price index indicates weaker and even weakening demand within domestic Chinese markets.

Since 2022, the core consumer price index for China has trended down, indicating diminished or diminishing demand for core consumer goods in China.

According to the Financial Times, this is the product of poor monetary policy, which Xi Jinping is committed to revising.

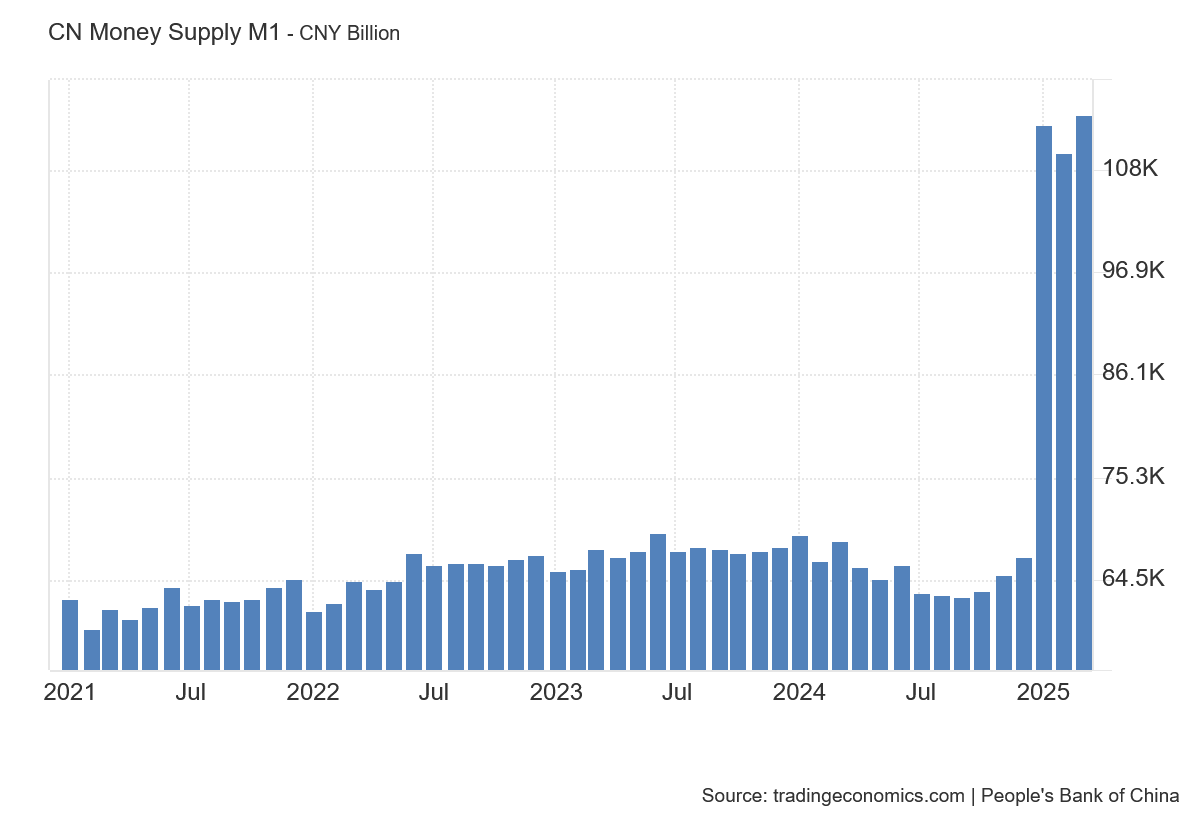

To be sure, the People’s Bank of China has injected a fair bit of fresh liquidity into their monetary system, boosting the M1 money supply by roughly ¥4 Trillion in March alone.

However, it would be inaccurate to characterize China’s monetary policies as “tight”. While Beijing did expand the money supply beginning in January, China’s monetary policy has always been far looser than US monetary policy, as the data going back to 2001 clearly shows.

When a country expands its money supply five times as much as the US has expanded its money supply, that country’s monetary policy is not at all “tight”, let alone “overly tight”.

Moreover, the pace at which China has increased its money supply suggests that China’s CPI data could actually indicate falling demand which is then being counteracted by monetary inflation.

If we proceed from the Friedmanite thesis that inflation is a monetary phenomenon, then we should expect to see major inflation in China, all things being equal. However, we have not. We see barely any inflation, and in core prices we are seeing either disinflation or even deflation. This is taking place in an environment where the money supply is expanding fairly rapidly. If we insist that the money supply produce an upward pressure on prices, then China is experiencing a downward pressure on prices that very nearly neutralizes the upward pressure.

If that’s the case, then Beijing’s additional goosing of the money supply is not going to have much impact on consumption, and the op-ed piece in the Financial Times is wrong.

We can further confirm the laxity of China’s monetary policy simply by looking at the balance sheet of the PBOC over time.

When the central bank increases its assets, it is expanding the money supply and loosening monetary policy. Debt instruments (assets, to a bank) are how central banks increase the money supply. If China’s money supply were the result of a tight monetary policy, we would not see a steady rise in the PBOC balance sheet.

That is confirmed by the steady rise in assets among private banks as well.

China has demonstrably had a very loose monetary policy for decades, yet it still has not been able to stimulate consumer demand!

What About Global Demand?

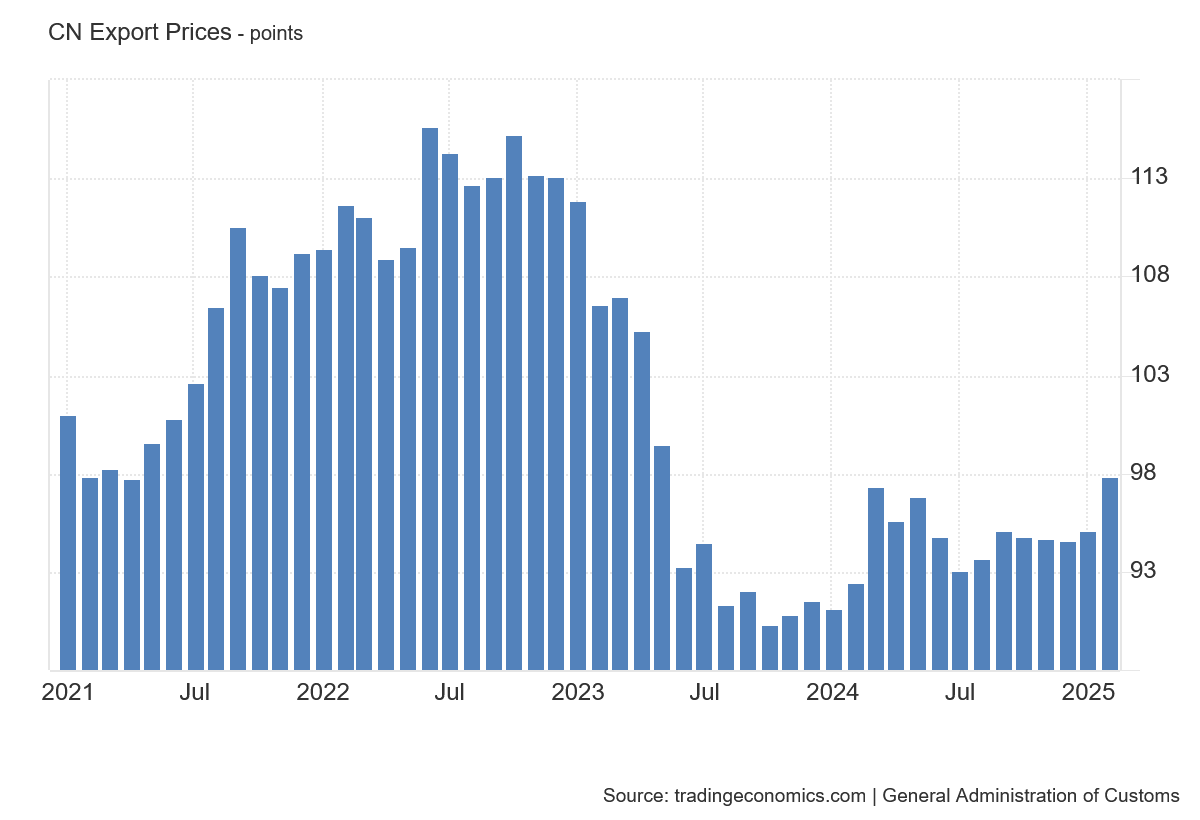

Global demand for Chinese products is hardly any better.

While export prices surged for China in 2021 and 2022, in the aftermath of the global lunacy of the COVID Pandemic Panic, since then they have retreated and largely stabilized.

Even with exports, the basics of demand and supply hold true, and a languishing export price index means there is not a lot of demand for Chinese goods on the world market at the moment.

Import prices tell a similar story. Where prices rose sharply in 2021 and 2022, they fell and then stabilized in 2023 and 2024.

With neither export nor import prices do we see signs of significant rising demand for Chinese goods and services.

When we look at the exchange rate for the Chinese yuan against the dollar, which has declined some 3% in recent years, we see even more indication that there is a lack of demand for Chinese goods, and further confirmation that monetary policy has been fairly loose.

A weakening currency generally has the same inflationary effect as expanding the money supply—the two phenomenon are often highly correlated within monetary policy. With a steadily weakening yuan in global foreign exchange markets, price levels should have responded by rising. They have not—or perhaps the monetary inflation is neutralized by demand deflation.

We should always remember that the constant caveat when describing the effects of individual economic phenomena—”all things being equal”—is always just a theoretical construct. In the real world all things are never equal, and the actual movement of prices is always the resolution of multiple forces pushing prices up and down.

At best, the behaviors of China’s export and import prices tell us that there is stable global demand, but not rising global demand for Chinese goods.

At worst, the behaviors of China’s export and import prices, coupled with the backdrop of currency depreciation, tell us that there declining global demand for Chinese goods.

About Manufacturing

The reality of a deflating economy is that manufacturing is never in good shape.

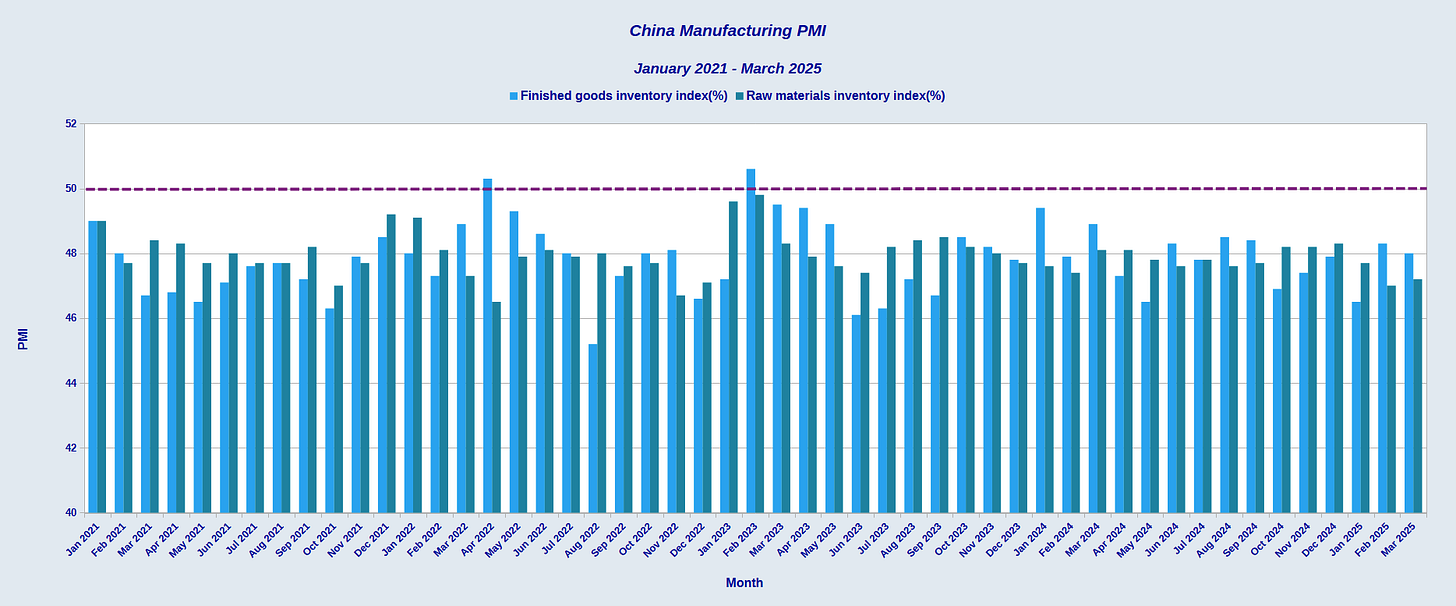

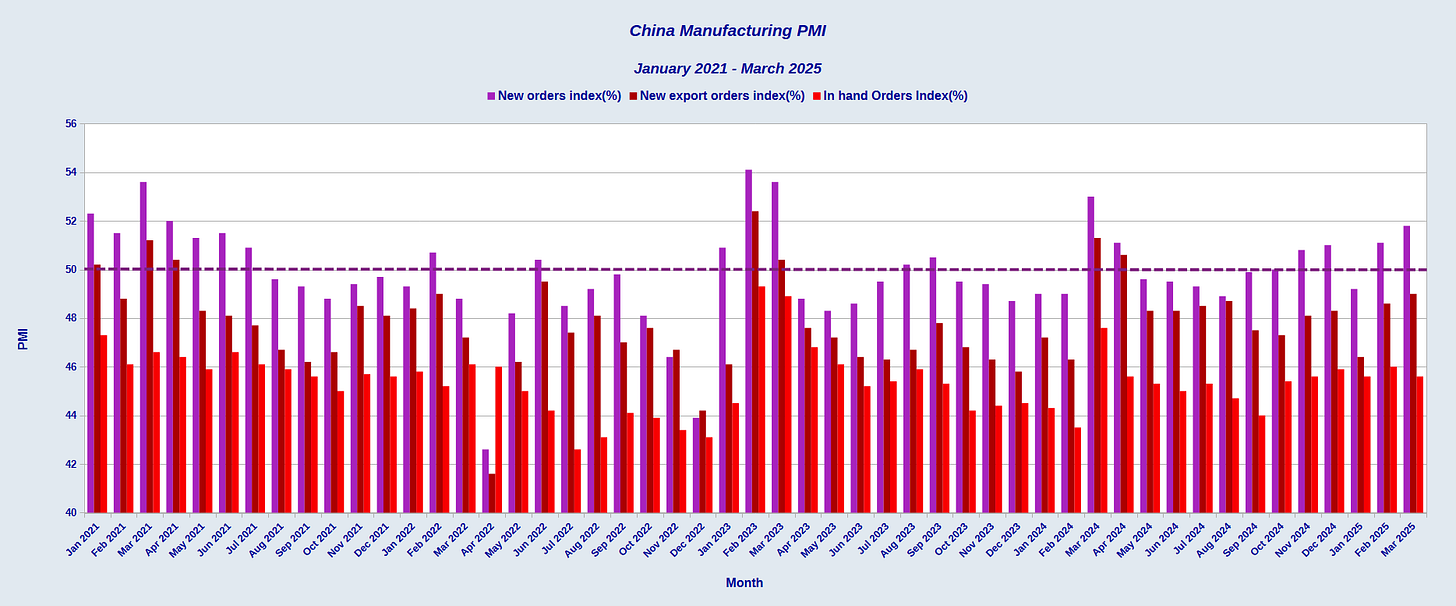

When we look as China’s Manufacturing Purchasing Manager Index data, we see that China’s manufacturing sector is very much not in good shape.

The key detail in understanding PMI metrics is that any value over 50 represents an expansion, and any value below 50 represents a contraction.

When we look at China’s official Manufacturing PMI metric, we see that the sector has been in contraction for a substantial portion of the past two years.

Already the top-level data is not looking good.

This does not mean that China is not producing goods. While the top-level metric has printed contraction, the production PMI metric has printed far more expansion.

We should note that, in recent months, both of these metrics indicate expansion. More production is always a good thing for the manufacturing sector.

However, the data doesn’t quite add up. While production has been largely in expansion, inventories for China have largely been in contraction.

Orders—both new orders and in hand orders—have likewise been largely in contraction, with the New Orders Index only just breaking through to expansion for the first time in months in November of last year.

Even worse for China has been the employment metric for manufacturing, which has been in almost unrelenting contraction since at least 2021.

Regardless of what China hopes people will infer from the headline PMI data, the detail does not say anything positive or upbeat about the state of China’s manufacturing economy.

These metrics are perfectly aligned with an economy that is trapped in deflation still—China has not succeeded since last I looked at this data in breaking out of that trap. These metrics are not at all aligned with an economy capable of withstanding any significant level of trade sanctions.

Housing Still In Crisis

We cannot discuss China’s economy and not talk about housing.

What is remarkable about China’s housing crisis is how long it has gone on.

Even as far back as 2021 it was apparent that China’s economy was being dragged down by its housing problems, and it was housing that turned the Chinese economy into “the sick man of Asia.”

Since then, the “sick man” has only gotten sicker, as sales of apartment units have declined steadily.

Sales of houses have also diminished.

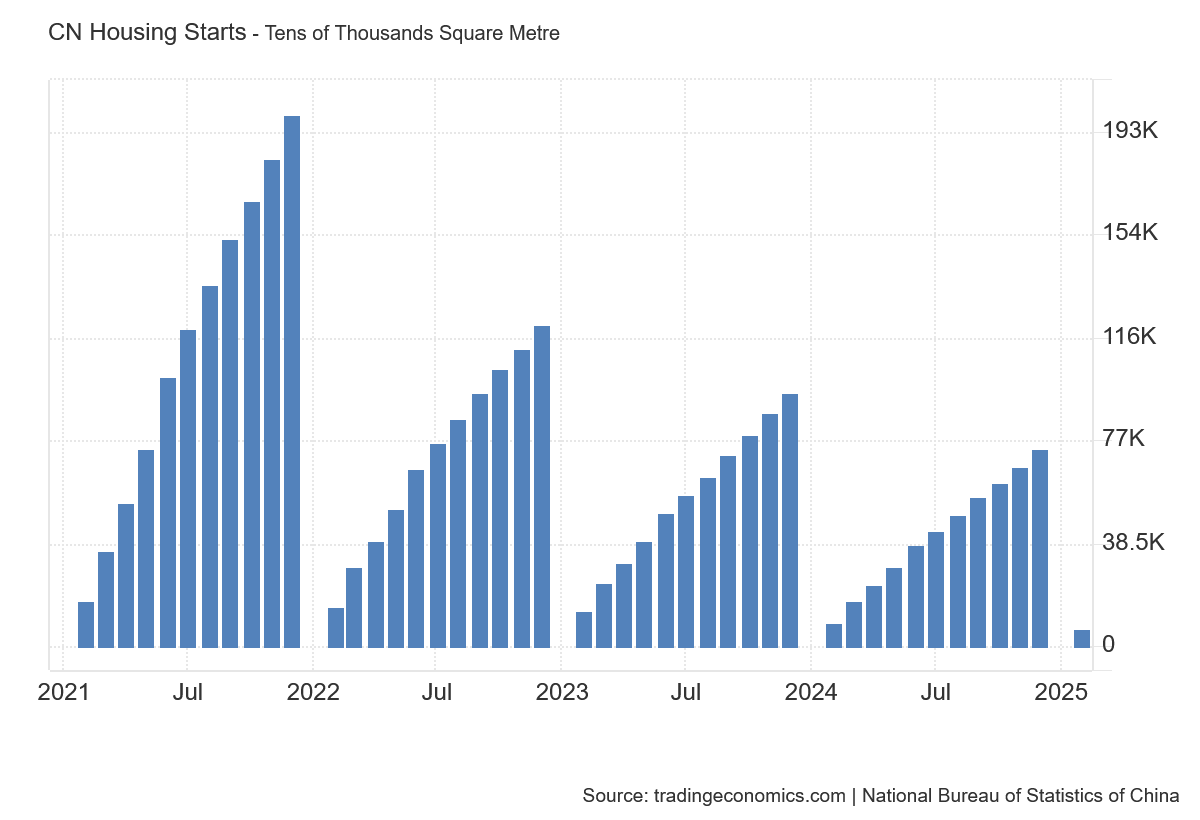

That the market is nowhere near done falling is underscored by the diminishing housing starts each year since 2021.

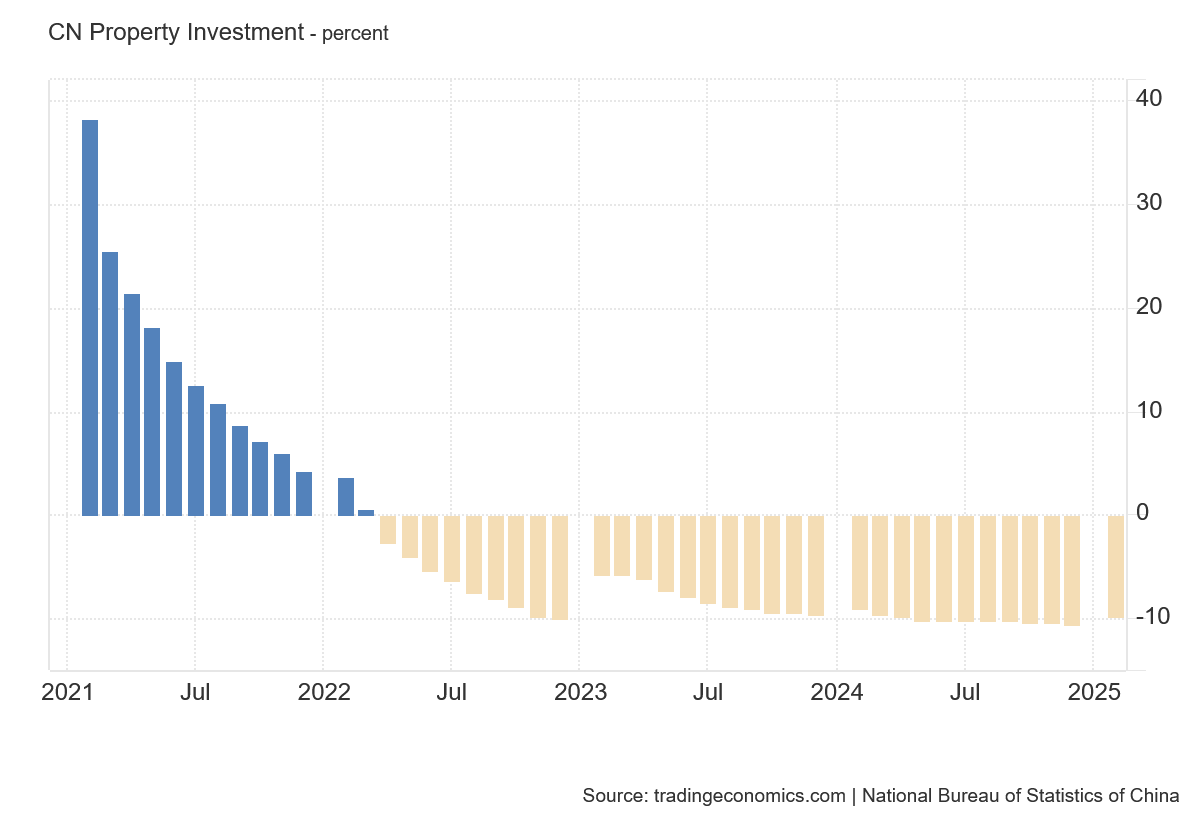

Property investment in China remains very much in freefall, and has for going on three years now.

From the first quarter of 2022, housing prices have declined, and continue to decline.

Even more distressing is that the price declines in the most recent quarter are the most significant price declines. The deflating of China’s property bubble appears to be accelerating, which means it still has quite some distance to go before it is done with the deflation.

Perversely, China’s official Construction PMI data serves to illustrate why the housing bubble is so large, and why it is taking so long to fully deflate:

With the Construction PMI printing expansion almost continuously since at least 2021, even in the face of collapsing home prices, China has persisted in building out still more housing, despite the housing sector being tremendously overbuilt.

With housing in China amounting to 25% of China’s overall GDP, the collapsing housing bubble is a principle reason China’s economy is mired in a deflationary downward spiral.

Who Wins A Trade War?

Does this data mean that China is fated to lose its contest of wills with President Trump?

Hardly.

As I have commented many times before, the US economy has its own challenges, and has its own vulnerabilities. There is an entire section of my Substack devoted to exploring those very issues.

The data here shows that China is not in great shape for fighting a trade war. That should not be taken to mean the United States is in great shape for fighting a trade war.

Xi Jinping himself articulates an important point, in a recent op-ed piece he published in Vietnamese media while on a trip to Vietnam: no one really “wins” a trade war.

He wrote:

“Our two countries should resolutely safeguard the multilateral trading system, stable global industrial and supply chains, and open and cooperative international environment.”

This is, of course, the classic articulation—as well as the classic defense—of the global maritime trading order that has emerged in the post-WW2 era, and especially after the 1992 collapse of the Soviet Union.

Xi’s statements are, of course, completely self-serving. Yet for all their grounding in Xi’s self-interest, they do drive home the point that the best outcome of any trade dispute is improved, balanced, and equitable trade among nations. The ideal outcome to this trade dispute is that the United States enjoys improved relations, is able to manufacture more, export more, and import more—all without incurring a permanent and substantial trade imbalance.

Whether that will happen is far from likely, and for all of Xi’s paying lip service to the virtues of engagement and improved trade relations, his remarks come while he is on a trip to curry favor among the nations of Southeast Asia particularly on trade relations. Xi is looking for trade allies and is hoping that Trump’s Liberation Day tariffs will help him find some. Even corporate media is willing to concede that point:

The timing of the visit sends a “strong political message that Southeast Asia is important to China,” said Huong Le-Thu of the International Crisis Group think tank.

She said that given the severity of Trump’s tariffs and despite the 90-day pause to "reciprocal" duties, Southeast Asian nations were anxious that Trump's policies could hinder their development.

Whether Trump’s policies are alienating countries or instead motivating them to negotiate with the Trump Administration over tariffs is a very much an open question. Obviously, if Xi is able to secure allies among the nations of Southeast Asia he can blunt at least some of the impacts of the Trump punitive tariffs imposed on China.

Contrary to the pontifications of corporate media—and even a fair amount of the alternative media—we do not know yet what the final outcome of President Trump’s trade dispute with China will be.

If Xi Jinping and China are less able to withstand the pressures being applied by President Trump and tariffs, Xi will be compelled to seek rapprochement with the United States on President Trump’s terms. Nominally, the United States would “win” the trade war under those circumstances.

If President Trump and the United States are less able to withstand the pressures being applied by Xi and his tariff responses, then it will be Donald Trump who will be compelled to seek rapprochement with China on Xi’s terms. Nominally, China would “win” the trade war under those circumstances.

Yet as this trade dispute drags on, there are sales by US companies in China that are not going to happen.

There are sales by Chinese companies in the United States that are not going to happen.

From a geopolitical and national security perspective, there are arguments for the United States to completely decouple from China, but from the economic perspective, such a decoupling of trade means trade overall is diminished.

There is no way a reduction in trade relations does not amount to a reduction in GDP for both the United States and China. Similarly, there is no way the disruption in trade relations that is the trade war itself does not amount to a reduction in GDP for both the United States and China.

That is the price that will be paid by both the United States and China as the cost of this trade war.

Whether China’s economy is in any shape to be paying such a price is, by the numbers, very much in doubt.

"There is no way a reduction in trade relations does not amount to a reduction in GDP for both the United States and China. Similarly, there is no way the disruption in trade relations that is the trade war itself does not amount to a reduction in GDP for both the United States and China."

This trade war is really squeezing the small to mid businesses and the repercussions will reverberate in our communities with foreclosures, unemployment and so so much stress. God have mercy on us.

Thank you for this thoughtful analysis.