China Is Trapped In Deflation With No Way Out

Beijing Fires Stimulus "Cannon" But It's Too Little Too Late

China has become the poster child for why government meddling in economics is an apocalyptically bad idea.

Far from becoming the world’s next number one economy, China is now trapped in a deflationary swamp, and the numbers say things will get much worse before they get better.

The release of China’s latest official Purchasing Manager Index data, which printed yet more contraction in manufacturing and continued softening in non-manufacturing sectors, underscores what is now obvious to one and all: China’s economy is not growing, but contracting.

The National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) purchasing managers' index (PMI) released on Monday nudged up to 49.8 in September from 49.1 in August, still below the 50-mark separating growth from contraction but beating a median forecast of 49.5 in a Reuters poll. The reading was the highest in five months.

It’s an odd sort of success when the economic data “beats” expectations by merely being less bad than anticipated. Yet such is the state of China’s economy that “less bad” is the best available.

As bad as the economic situation in the United States is—and it’s not at all good—the data shows China’s situation to be considerably worse.

As already noted, China’s PMI data shows the economy to be contracting across multiple sectors.

The headling Manufacturing PMI has been printing contraction for months.

Any PMI number below 50 represents a contraction, and with few exceptions China’s Manufacturing PMI has been contracting since early 2023.

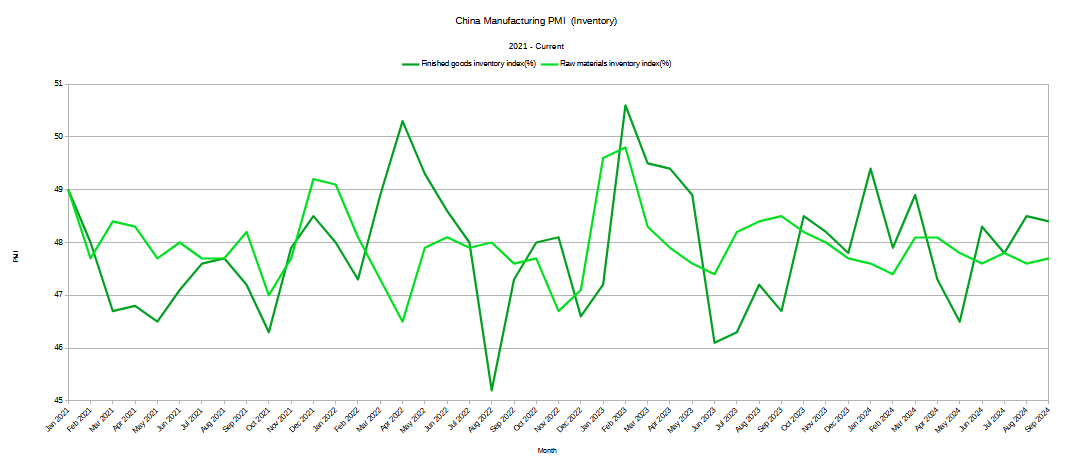

Yet it’s not just the topline Manufacturing PMI that is in contraction. Drilling into just about every component of manufacturing also shows contraction.

Factory orders are on the decline.

Inventories are on the decline.

What is most disconcerting abot these subordinate PMI metrics is that they are showing steady contraction—the numbers are stubbornly below 50 consistently. The contractions are not transient aberrations but are instead long term trends.

Even purchasing activity is in contraction within China.

Less purchasing, less inventory, fewer orders — these are not the long term industrial trends from which growth and prosperity can emerge.

When we look at intermodal freight activity in China, we another alarming trend — freight activity has largely plateaued during 2024.

When total ton-kilometers is constant or declining, it means that China is not moving a growing number of goods, and an economy that doesn’t move more stuff cannot be growing.

Again, when we drill into the subordinate metrics, we see the trend being sustained.

Rail freight is actually declining.

Waterway traffic itself has largely plateaued, with a moderate trend downward.

No matter what the narratives might suggest about the state of China’s economy, how can there be substantive economic growth if the same volumes of goods or less are being moved around the country?

Nor is China getting much help from the non-manufacturing sectors of the economy.

With the topline number right on the bubble, printing at a neutral 50, new orders is showing contraction just as it is examining the underlying data for the manufacturing PMI.

With businesses booking fewer and fewer orders, there is no stage being set for future economic growth. Rather, the stage is being set for ongoing economic contraction.

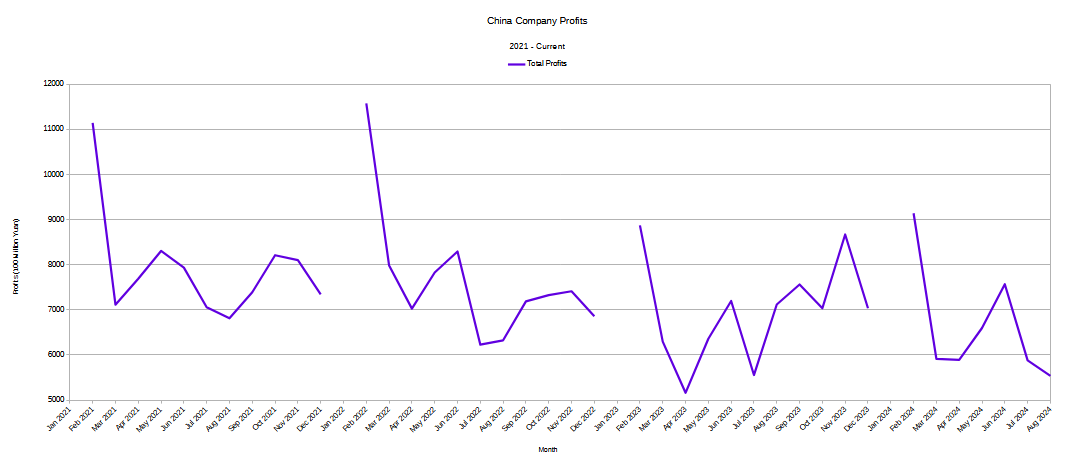

With manufacturing businesses especially doing less business, there is no surprise to find that profits are down in China—way down.

The 17.8% drop was the steepest since an 18.2% drop in April 2023, according to official data accessed through Wind Information.

The statistics bureau attributed the large decline in August to a high base in the year ago period. In August 2023, the same monthly figure expanded 17.2% from a year ago.

The drop dragged down industrial profits for the year. In the first eight months of the year, profits at large industrial firms grew by 0.5% to 4.65 trillion yuan ($663.47 billion), compared with a 3.6% increase in the first seven months.

Spin aside, the reality is that China’s businesses have been experiencing profit shrinkage for months.

Even the year on year change in profits has been consistently negative.

Fewer orders mean less business mean less profits. The economic math on this point is simple, blunt, and brutal.

While it would be an exaggeration to say that China’s economy is in a state of collapse, it is equally and exaggeration to speak of China’s economy growing. No matter what the GDP data might show, virtually every other indicator is flashing contraction. Not only is China not likely to meet its 2024 GDP growth goal of 5%, in reality the Chinese economy has almost certainly contracted thus far in 2024, and with zero signs that there will be any expansion at all in the coming months.

Small wonder Beijing decided to fire its “stimulus cannon” at the economy. Even more remarkable, however, is the panicked way in which Xi Jinping is unleashing stimulus, matching it with calls within the CCP rank-and-fil for policy “innovation”.

“The vast number of party members and cadres must have the courage to take responsibility and dare to innovate,” said a readout from the meeting, which was chaired by Xi.

The readout also mentioned the term “three exempts” – exempting well-meaning officials who make mistakes due to lack of experience; exempting officials who make mistakes in experiments, especially those in new domains without clear restrictions; and exempting officials who inadvertently err when promoting development.

“The fact that this ‘responsibility and punishment waiver’ is reaffirmed at today’s Politburo meeting, at which Beijing issued the most urgent call-out to fire up economic growth, is significant,” said a political scientist with Peking University who declined to be named as they were not authorised to speak to non-state media.

As I wrote in a Note the other day, given the extent of Xi’s cult of personality within the CCP, such a call for policy innovation is tantamount to policy failure at the top of the CCP leadership.

But the cry for policy “innovation” is itself remarkable in a system that has been marked by top-down thinking even before Xi assumed control, and has only become more centralized during his tenure. Asking mid-level bureaucrats to “innovate” means the top-level people have run out of ideas. By definition any time someone asks someone else to innovate there is a lack of ideas on one side of the equation.

After over a decade of “anti-corruption” purges which have effectively removed most if not all independent thinkers from the CCP cadres, exactly where Xi hopes to find this “innovative” policy thinking remains something of a mystery.

While Xi is hoping for policy innovation within the ranks of the CCP, the current firing of Beijing’s “stimulus cannon” is proving to be a rather conventional and largely unimaginative set of measures intended to bolster China’s collapsing housing markets and stabilize that crucial economic sector.

A primary nexus of China’s economic woes is that home sales are still languishing, and are continuing to trend down despite previous efforts to revive the sector.

This downward pricing trend is carrying over into China’s rental markets, which is seeing continued rent price deflation for most of 2024.

Predictably, China’s stimulus measures are targeting these moribund markets, seeking to revive their flagging fortunes, including slashing interest rates and the required reserve ratio for banks in order to stimulate mortgage lending.

The reserve requirement ratio (RRR) – the amount of cash that commercial banks must hold as reserves – and the mortgage rate for existing housing would be cut by half a percentage point, according to People’s Bank of China governor Pan Gongsheng.

The PBOC would also support the acquisition of real estate companies’ lands by studying measures to allow policy and commercial banks to grant loans to eligible companies to acquire the land, revitalise the stock of the land and ease the financial pressure on real estate enterprises.

As more than one analyst has noted, however, these efforts fail to address the causes of falling home sales: low and falling housing demand.

The measures the CCP announced are intended to make it easier for Chinese people to access capital and buy property, but access to debt is not the problem here. People in the country do not want to spend money because they are already sitting on large amounts of real-estate debt tied to declining properties. Seventy percent of Chinese household wealth is invested in property, which is a problem since analysts at Société Genéralé found that housing prices have fallen by as much as 30% in Tier 1 cities since their 2021 peak. Land purchases helped fund local governments so they could spend on schools, hospitals, and other social services — now that financing mechanism is out of whack. Sinking prices in these sectors, or what economists call deflation, has spread to the wider economy. The latest consumer price inflation report showed that prices rose by just 0.3% in August compared to the year before, the lowest price growth in three years, prompting concerns that deflation will take hold, spreading to wages and killing jobs.

Moreover, as I mentioned in an earlier Note, spurring new home sales does not address the fundamental imbalance within the economy the housing bubble represents.

No amount of stimulus can get around the reality that China’s housing woes stem from the housing bubble previous stimulus efforts catalyzed.

Not only is China’s housing market overbuilt by a couple of orders of magnitude, but housing prices are far above what current housing demand can support.

This is a problem for Beijing, because the housing correction that MUST come is that housing prices must fall. When those prices fall, the 70% of “middle class” Chinese whose wealth is tied up in real estate will see that wealth evaporate.

After the real estate disruptions and developer bankruptcies of the past few years, the average Chinese has lost his or her enthusiasm for taking on significant mortgage debt to buy even one property—but without fresh home sales indebted developers are still unable to raise the funds to finish existing real estate projects.

Stimulating the housing markets under these conditions is always going to be counterproductive. The most that such stimulus can accomplish is postponing the inevitable household wealth destruction that China must undergo in order to bring housing markets back into any sort of equilibrium.

Yet until China moves through this inevitable—and excruciatingly painful—cycle of wealth destruction, there is no way for stimulus measures to spur new consumer demand.

Chinese citizens are saddled with housing debt for homes in which they cannot live in many cases, reflecting housing prices that are inflated by multiple orders of magnitude. Those same housing prices are also the benchmark for the average individual’s store of savings in China, where housing rather than the stock market is the principal savings vehicle.

Faced with high debt and disappearing wealth, Chinese citizens are going to be a long time building any serious level of consumer demand with which to spur the economy.

As I noted over two years ago, by far the biggest and most intractable aspect of China’s economic woes is the extent to which the problems are all a series of “own goals”.

Zero COVID has served to accelerate trends that were causing China to lose manufacturing jobs to Southeast Asia and elsewhere even before the pandemic. For a number of years, there has been a steady migration of manufacturing away from China to labor markets with even cheaper labor—China has not been the “least cost” producer of goods for quite some time. Labor markets such as Vietnam and India now have the added benefit of not being governed by demonstrable psychopaths.

Despite China’s dogged insistence that Zero COVID is grounded in science, the reality of Zero COVID has instead been the epitome of Faucism. The policy is sustained not because of its scientific merits, but because the Chinese Communist Party, from Xi Jinping on down, dare not suffer the loss of face attendant upon admitting the policy was a mistake.

At the time, the focus was on China’s disastrous “Zero COVID” policies, but the theme of government and bureaucratic error survives into present moment. At the epicenter of all the economic mismanagement: Xi Jinping.

China’s downward deflationary death spiral largely began when Xi issued his “Three Red Lines” to rein in real estate developer debt—and by so doing cut them off from the very debt markets they needed to finish numerous housing units which the developers had already sold.

Zero COVID added to the damage by squelching what little consumer demand exists in China.

With the collapsing housing market and loss of housing wealth on the one hand, and Zero COVID having suppressed most other forms of domestic consumption on the other, Xi Jinping has painted the CCP into a corner. Xi cannot stimulate domestic consumption or resurrect the housing markets until the average Chinese citizen endures the destruction of some two-thirds of his househod savings and store of wealth.

Let that thought sink in: In order to reach a point where government policy stimulus is even feasible, Xi has to make the bulk of people’s accumulated wealth simply vanish.

China thus stands as a grim object lesson for the world’s other economic interventionists. Government meddling with an economy invariably meets with disaster.

Whether we are talking about China or the United States, or Great Britain, or even the EU, the object lesson is the same: governments cannot contend with every little variable that impacts a nation’s economy. In many instances governments are not going to even have the data, and in other instances they have the data but fail to appreciate the consequences.

In every instance the end result is the same: policy error and economic damage.

There is not space sufficient within a single Substack article to explore all the ways Beijing has wrecked China’s economy. However, it is enough to note that what Beijing has done is wreck the Chinese economy.

What every government does when it meddles in its country’s economy is wreck that economy.

Politicians who promise greater government intervention in an economy are, in every instance, championing policy error and economic disaster—and their ideas should be rejected on that basis.

Thanks to Xi Jinping’s catastrophic series of economic blunders, the world need no longer contemplate the question of when China will become the world’s largest economy. Instead, we are now faced with the question of when China will become the world’s largest economic failure.

The answer to that question is likely to be “Soon.”

Brutally grim data regarding China, and another unassailable analysis by Peter. You’re so smart that I’m going to have to dig out a thesaurus to come up with more synonyms for ‘brilliant’, Peter.

When the USSR mired itself in economic malaise during the 1970s and 80s, the social response was a nation of vodka-swilling drunks, too demoralized to even attempt solutions. I don’t see the young people of China having a similar cultural response. Will they just pass their lives away playing video games, ‘lying flat’, and virtually hanging out with the 20%+ of their generation who are unemployed? Or will a significant percentage of them rise up, find ways to circumvent the CCP, and create a better future for themselves? I don’t know, but I’m counting on the inherent creativity and passion of human nature to at least try!

Their future could be filled with more ‘interesting times’ than we can now imagine.

Reason number 1467 communism doesn’t work.