Wall Street has a problem.

Actually, Wall Street has several problems, so we’ll focus on just one for now: Wall Street’s Treasury portfolios are losing money.

Worse, Wall Street’s Treasury portfolios are losing money in ways that make bond fund managers seem amateurish and short sighted.

Last year’s steep losses were easier to explain to clients — everyone knows bond prices suffer when inflation is high and central banks are driving up interest rates.

The expectation in 2023 was that the US economy would crater under the weight of the sharpest run of hikes in decades — bringing gains for bonds on the expectation of policy loosening to come.

Instead, even as inflation slowed, jobs data and other key measures of the economy’s health remained strong, keeping the threat of faster price growth ever-present. Yields catapulted to highs not seen since 2007, putting the Treasury market on course for an unprecedented third year of annual losses.

Another way to view Wall Street’s bond problem is that it has run out of excuses for not understanding what was bound to happen as the Fed began tightening monetary policy. The Fed was supposed to have backed down on rates by now, which would have rescued bond fund managers from themselves.

Why are bond portfolios losing money? Because interest rates are rising, which makes existing bonds intrinsically less valuable than bonds yet to be sold.

To apprehend the particular lunacy of Wall Street’s struggle with deteriorating bond portfolios, it is important to note once again that interest rates began rising in December of 2021, a full three months before the Fed officially began “raising rates” by increasing the federal funds rate.

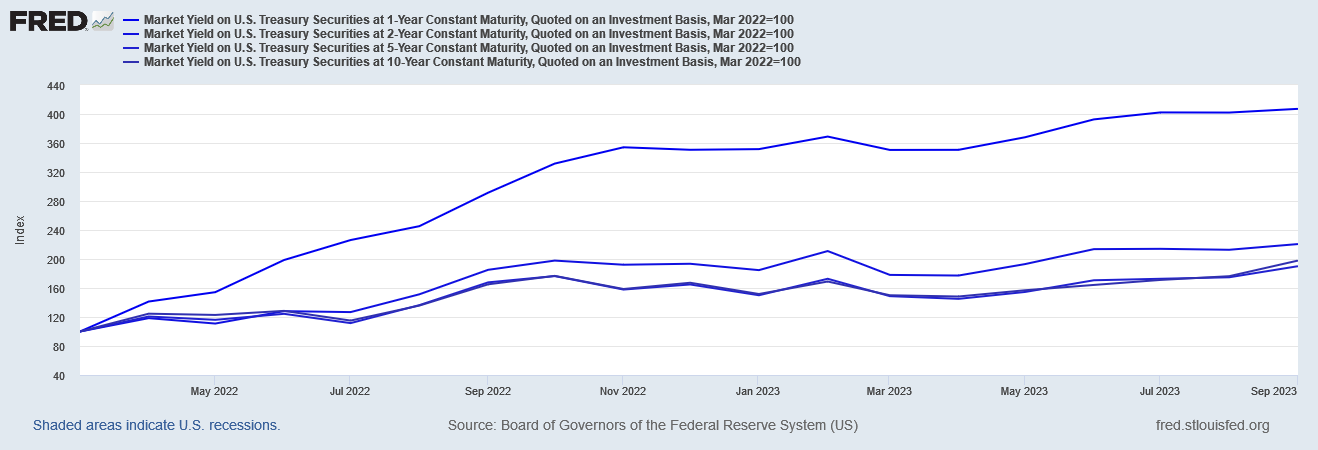

If we index Treasury yields to January 1 of 2021, we see that by March of 2022, they had risen more than tenfold for 1-Year and 2-Year Treasuries, more than fourfold for the 5 year Treasury, and nearly doubled for the 10-Year Treasury.

In other words, well before the Federal Reserve officially began “raising rates”, Wall Street bond portfolios began losing their value.

As I have mentioned previously, in discussing the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, everything that Wall Street is encountering now was painfully obvious well over a year ago (now almost two years ago).

In the case of rising interest rates and their impact on bond portfolios, that there would be a loss of value was apparent almost two years ago.

More importantly, Wall Street’s own best information source—the markets—was communicating exactly what was happening. When we look at how Treasury Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs) performed from January 2021 through March 2022, we see that for all maturities the funds lost value.

When ETFs focusing on longer Treasury maturities lose more that 15% of their value during the run-up to the Fed’s first rate hike, that should have been a clue that bond portfolios would shed value.

Interestingly enough, when we look at the relative increase in Treasury yields in response to the Fed’s rate hike strategy on inflation, one of the first things we have to note, especially for the lower maturities, is that the relative increase in interest rates after the Fed started hiking the federal funds rate has been less than the relative increase in interest rates between January 2021 and March 2022.

The 1-Year Treasury yield increase just over fourfold during the Fed’s rate hike strategy period, unlike the period from January 2021 through March 2022, when the 1-Year Treasury yield increased ten times over.

In other words, raising the federal funds rate has had a relatively muted impact on market interest rates. In terms of relative magnitude, the far greater, far more impactful shifts in interest rates occurred within the 1-Year and 2-Year Treasuries just prior to the first federal funds rate hike.

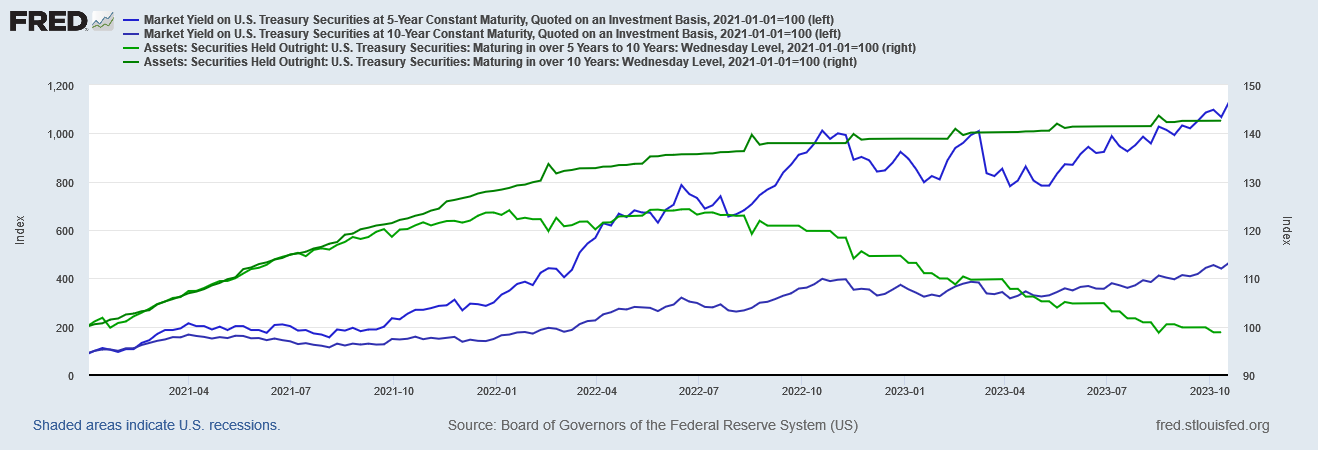

Note also that this initial phase of rises in Treasury yields occurred while the Fed’s portfolio of Treasuries was increasing.

Interest rates began rising not only before the Fed began increasing the federal funds rate but also before the Fed stopped its programs of purchasing Treasuries. This is significant because the Fed’s Treasury purchases have been instrumental in keeping yields down—yet failed to do so after the fall of 2021.

If we look closely at the breakdown by maturity of Treasuries held by the Federal Reserve, we can begin to divine the reason yields for 1-Year and 2-Year Treasuries rose so much more rapidly relative to a January 2021 base:

The Federal Reserve began focusing more purchases on the longer term treasuries and fewer on the shorter term maturities. With fewer Fed purchases of 1-Year and 2-Year maturities, interest rates on 1-Year and 2-Year bonds naturally rose—exactly as they should.

If we focus on the longer maturities, we see similar behavior there as well.

The 5-Year Treasury yield has risen more than the 10-Year Treasury Yield at the same time that the Fed has purchased more 10-Year and longer Treasuries and fewer 5-Year Treasuries.

Incidentally, these yield dynamics also suggest that the Fed would have done better on interest rates to make asset purchases of Treasuries the focus of its inflation strategy and not the federal funds rate.

While rising interest rates alone increase the value of newer Treasuries over older ones, the situation has been compounded by the stead climb in real yields out of the negative range where they have languished since the Pandemic Panic Recession. After June of last year, when energy prices began to fall, the overall inflation rate as measured by the Consumer Price Index also began to fall. Coupled with rising Treasury yields, this steadily moved interest rates towards and then above the zero bound.

Once again, it is worth noting that significant progress in real yields did not occur until after energy prices peaked in June. As the fall in inflation tracks to the fall in energy prices, the rise in real yields towards the zero bound also tracks to the fall in energy prices. As we see clearly if we focus on 2023, real yields began to turn positive in May, and have been fully positive since June.

We can gauge the impact of this on Treasury portfolios by looking at the decline in Treasury ETFs starting from May 1st of this year.

In the latter half of May there was a small but significant drop in ETF valuation, with a major drop-off in value occurring in July. While it would be dangerous logic to ascribe 100% of the decline in value to real yields turning positive, it takes no stretch of imagination or of logic to conclude that the real yield shift from negative to positive magnified the loss of value among Treasury ETFs.

The net effect of these dynamics has been to steadily degrade the value of bond portfolios since 2021.

Yet if bond portfolios have been losing value since early 2021, then we are left with the question of how Wall Street bankers and bond fund managers are, in late 2023, left worrying about collapsing values of Treasuries and funds invested in Treasuries?

The answer, ultimately, is a simple one: Wall Street keeps drinking its own Kool-Aid and has refused to wean itself off low interest rates, low yields, and cheap money courtesy of the Federal Reserve.

It was this refusal to face reality that ultimately led to Silicon Valley Bank’s demise (and later First Republic).

However, even early in the year, despite over a year of warning signs and red flags, fund managers watched various bond indices showing a positive return on the year and convinced themselves that bonds were headed in a good direction.

US debt markets are above water this year, with the Bloomberg corporate bond index showing a return of 0.45%, quite a turnaround from the almost 16% loss of 2022. The high yield index is returning 2.34% in 2023, also an about-face from an 11% loss last year.

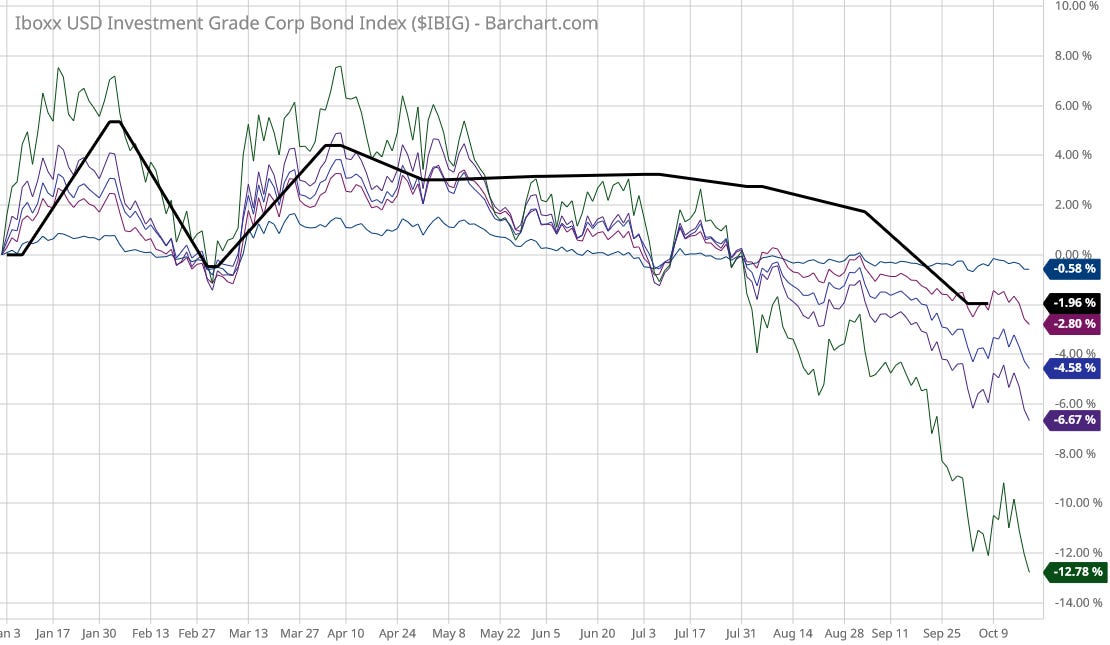

Ironically, corporate bond indices have largely mirrored the performance in Treasury ETFs from 2021 until now.

In other words, even the overall market behavior has been telling Wall Street all along that bonds were headed for rough waters—and doing so since well before the Fed began hiking the federal funds rate.

Despite this, and despite the obvious negative trends within Treasury ETFs, Wall Street still believed that the incremental increases in bond indices at the start of the year signaled a coming good year for bonds.

US debt markets are above water this year, with the Bloomberg corporate bond index showing a return of 0.45%, quite a turnaround from the almost 16% loss of 2022. The high yield index is returning 2.34% in 2023, also an about-face from an 11% loss last year.

Why did Wall Street believe this? In part because corporate bond indices did not register the same valuation drop in May that Treasury ETFs did.

The high-yield indices have bucked the ETF trend even more, breaking away from the general pattern of ETFs—again, starting in May when real yields began to turn positive—and have until recently even risen year to date.

Wall Street deluded itself that real yields turning positive was not another red flag against the valuations of bond portfolios. The market indicators were telling them the exact opposite and yet they still managed to reach that conclusion.

Yet if all this data were not enough, Wall Street also had (and ignored) the most blatant indicator of all—that the Fed has been tapering off its bond purchases at the same time it has been raising the federal funds rate.

Market yields are driven, like all market prices, by the confluence of supply (the US Treasury issuing bonds) and demand (the market buying bonds). For years the Federal Reserve has been buying bonds on the open market, thereby boosting prices (remember, bond yields are the inverse of actual bond price, so that as bond prices go up, bond yields go down). When the Fed reduced its bond purchases, it reduced the actual market demand for those same bonds by definition.

Falling market demand means falling price means loss of value for any asset—stocks, bonds, and even real estate all adheres to this fundamental principle. The Fed is reducing market demand for Treasuries by buying less of them, which reduces market prices for Treasuries (thus pushing market yields up), reducing the market value of Treasuries. On this one fact alone it is inevitable that Treasury portfolios would lose money once the Fed committed to raising interest rates.

Quite simply, Wall Street has managed to forget that Fed bond purchases are what have kept rates and yields down, and the tapering off of bond purchases by the Fed is what is pushing rates and yields up. Instead, Wall Street has maintained a fixation on the premise cited at the beginning, that economic indicators would show recession and contraction in the US economy sometime this year, forcing the Fed to reverse course on interest rates.

Now that the Fed is promising to keep rates higher longer—while continuing to reduce its volume of bond purchases, ensuring actual yields will continue to rise—reality is setting in for bond indices, and pulling them back down to where the ETFs have been all along: underwater.

As has repeatedly been the case with Wall Street, there are no real surprises. The data has always shown what common sense and the inexorable mathematics of rising interest rates say should be: rising interest rates, and even just higher interest rates, make existing bonds less valuable than newly issued bonds. This has always been true and always will be true.

Consequently, it has always been a given that, as the Fed has persisted in sustaining a strategy of trying to push up interest rates, bond portfolios would always end up in the negative. There has never been any possibility of any other outcome. The Federal Reserve’s rate hike strategy to fight inflation was guaranteed to make bond investments into collateral damage.

Interest rates are continuing to head up. Yields are rising, and will continue to rise. As yields continue to rise, the valuations of current bond investments will continue to decline. Wall Street forgot this will always be the financial order of things. Now, with the Fed hinting at another rate hike in the offing, while continuing to reduce its balance sheet, Wall Street is finally getting a long-overdue reality check.

Ugh, in 2020/2021 we went into bond etfs and funds since adjustment was prudent being within 6y of retirement and facing health issues and now the ballast portion is sunk, so underwater it’s staggering. Need to decide if we should turn off automatic reinvestment, but cost basis is killing the value. No other choice but to stay the course bc it’s all in IRA and someday (decades?) we’ll be made whole? I feel so stupid but it made sense at the time to adjust AA on risk and life events.

Good analysis as usual. David Haggith had a good read as well today - It's All Collapsing Now, and There is No Way out! - https://www.thedailydoom.com/p/its-all-collapsing-now-and-there

Will be linking both of your articles today @https://nothingnewunderthesun2016.com/

Seems that most analysts I read are pretty much in agreement on this one other than the talking heads on TV!!!