"Too Late" Powell About To Make Another Big Mistake

The Data Demands A Big Rate Cut Powell Won't Make

The great lingering question after the Silly Schumer Shutdown has been whether the Fed will or will not trim the federal funds rate when the Federal Open Market Committee meets in December.

For the first time in quite some time, Wall Street has grappled with considerable uncertainty regarding the FOMC’s next rate decision. For a time investors were pricing in that there would be no rate cut, but as of this past Friday Wall Street had reversed yet again and is now pricing in a 25bps rate cut.

Yet there should be no uncertainty about this question. The arguments in favor of not just a 25bps rate cut, but a 50bps or even a full percentage point reduction are compelling and increasingly persuasive.

On multiple fronts there is mounting evidence that not only is the US not at full employment, but that the economy as a whole is simply “stuck”—possibly even drifting into stagflation or outright deflation—while at the same time there are increasing signals of funding and liquidity stress within the US financial system.

Once again, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell has proved the accuracy of his Trumpian moniker “Too Late”. The data is pointing increasingly to Powell having committed a policy error at least as big as holding to the narrative of “transitory inflation” in 2021 and 2022, allowing the hyperinflation cycle to take off before responding. Powell was “Too Late” then, and it is increasingly apparent that he is “Too Late” now.

Whether a shock rate reduction will have the necessary beneficial effects this late in the day is of course problematic. What is not problematic is that the US economy’s current trajectory is not a good one, no matter how much “Golden Age” cheerleading we get from the Oval Office.

As Jerome Powell moves into his final months as Federal Reserve Chairman, it is likely that his swan song will be steering the US into worsening recession, possibly even a depression.

That’s not a Christmas gift any of us want.

Wall Street Should Be Nervous

The extent of Wall Street’s jitters over what the FOMC will do in two weeks’ time has been quite significant. That much is obvious from the see-saw routine their rate-cut probability estimates have displayed since the government re-opened.

Currently, Wall Street is projecting a 69% probability the FOMC will trim the federal funds rate by 25 basis points. Yet just a week prior that probability had dipped below 50%, with the Street projecting a 44% chance of a 25bps rate cut.

At the end of October the probability was in its usual near-certain range at 91%.

Much of the angst is arguably performative, as corporate media has been pushing a narrative that the Federal Reserve is “flying blind” after the government shutdown disrupted many of the primary metrics published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the Bureau of Economic Analysis, with the Trump Administration declining to work to remediate the data gaps before the FOMC meeting on December 10-11.

Those who follow me on Substack Notes already know what I think of this narrative (not much).

Yet there are real reasons for the angst that go beyond the “flying blind” narrative.

There have been worrisome signs that financial markets are heading into another banking and liquidity crisis on par with the subprime mortgage debacle of 2007 and subsequent Great Financial Crisis of 2008-2009. This time the flash point is shaping up to be private credit, which has proliferated in recent years (a growth trajectory not dissimilar to that of subprime mortgages in the early 2000s).

The first warning sign was the September collapse of subprime auto lender Tricolor. which filed for bankruptcy amid allegations of fraud.

The next domino to fall was the abrupt October collapse into bankruptcy of US auto parts maker First Brands, which revealed significant—and unexpected—exposures for private credit firms on both sides of the Atlantic. US-based investment bank Jeffries reported outstanding debt from First Brands of $715 million, while Swiss-based UBS O’Conner reported $500 million in overall exposure.

Just two weeks ago that same scenario played out again, this time with the sudden shutdown of Renovo, a home improvement conglomerate. Just a week prior, investment firm BlackRock valued its holdings of $150 million in private Renovo debt at face value—100 cents on the dollar. With the bankruptcy and shutdown announcement, BlackRock is facing the total write-off of that debt.

The common denominator in all of these abrupt bankruptcies is the involvement of so-called “private credit”, which is simply various forms of credit and lending extended to businesses by non-bank institutions (e.g., investment fund managers such as Apollo Global Management and Blackstone). In recent months, there has been a surge of such private lending by non-banks, lending which takes place outside of usual credit channels, thus falling outside normal risk management controls and regulations.

Perversely, many of these non-banks—”Non-Depository Financial Institutions” (NDFI) in financial argot—are in turn either owned or funded by regular banks, meaning the banking system itself is tied into these private credit arrangements. Financial services firm Moody’s observed in a special report late last month that these relationships were reshaping credit risk across the banking sector.

Banks have also been entering significant partnerships with alternative asset managers to diversify income and risk. But banks and these asset managers also remain staunch competitors — particularly in the fight to provide financing for leveraged buyouts and sponsored finance.

As banks compete with non-bank lenders and simultaneously finance them, asset quality challenges may surface. The recent bankruptcy of Tricolor shows that bank lending to NDFIs can result in significant losses, and underwriting and collateral controls can fail even when loans are secured.

Banks’ lending to private credit providers rather than directly to middle-market borrowers offers a diversification benefit from exposure to the providers’ wide spectrum of portfolio companies. But this benefit is reduced by the incremental leverage that private credit providers often incur at the portfolio company level, and the inherently lower transparency of indirect lending. These evolving dynamics underscore the need for vigilant credit risk management as private credit continues to scale up.

We may already be seeing early signs of financial system stress from the explosion of private credit.

Beginning in September, right around the time Tricolor went under, the Fed’s Secured Overnight Funding Rate moved above the Federal Funds Effective Rate, where it has remained ever since.

The Secured Overnight Funding Rate is, per the New York Fed, “a broad measure of the cost of borrowing cash overnight collateralized by Treasury securities”. This rate reflects overnight borrowing and repurchase activity, used by banks for quick infusions of cash and liquidity. Since September, the cost of those liquidity infusions has been rising relative to the federal funds rate, when historically it oscillates around the federal funds rate.

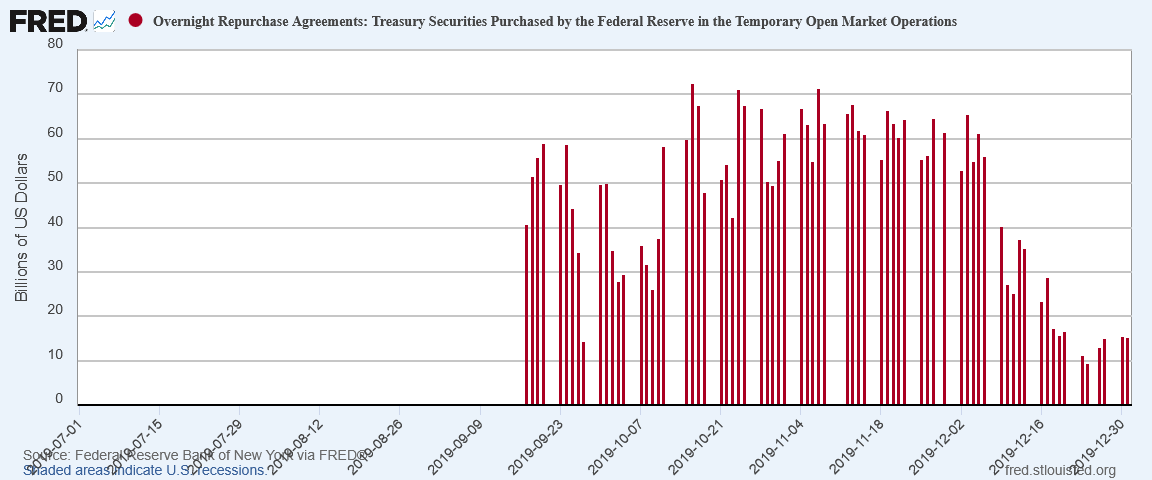

This rise in the SOFR may be a factor in the increased use of Overnight Repurchase Agreements with the Federal Reserve, the volume of which surged at the end of October, and which has been considerably greater than normal since mid September.

The last time we saw this sort of increase in repo activity was in the last half of 2019.

The increased need for such “emergency” cash infusions by banks helped convince Jerome Powell to lower interest rates ultimately by a full percentage point between August and November of that year.

Just on this bit of history rhyming alone the FOMC needs to be contemplating more than a 25bps rate reduction.

Jobs Recession Stands In The Way Of Full Employment

Another dimension to the Fed’s interest rate assessment has to be its mandate to facilitate full employment in the US economy.

With the jobs recession now stretching well into a third year, it is painfully obvious that we are nowhere near full employment.

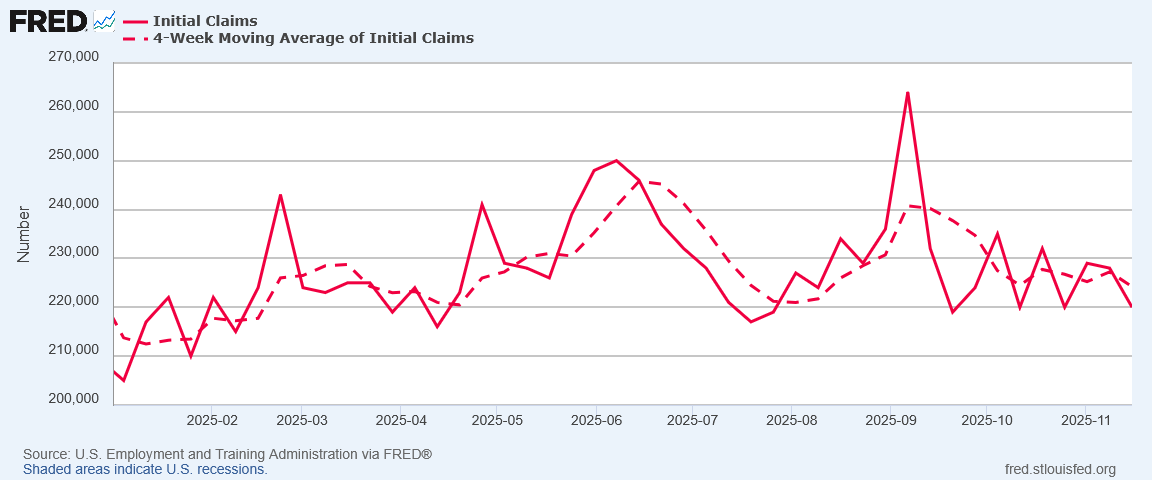

The unemployment data bears this out. After rising steadily earlier in the year, initial unemployment claims have been largely consistent since mid-July.

While there has been a slight downward trend over the past two months, the level is still well above where it was at the beginning of the year. By definition, this represents an increase in joblessness.

This is confirmed by the continued rise in continuing unemployment claims.

While in recent weeks there have been fewer people filing initial claims, those that do file claims are increasingly remaining unemployed for longer periods of time.

The net effect is easily seen in the steady rise in the unemployment level since 2023.

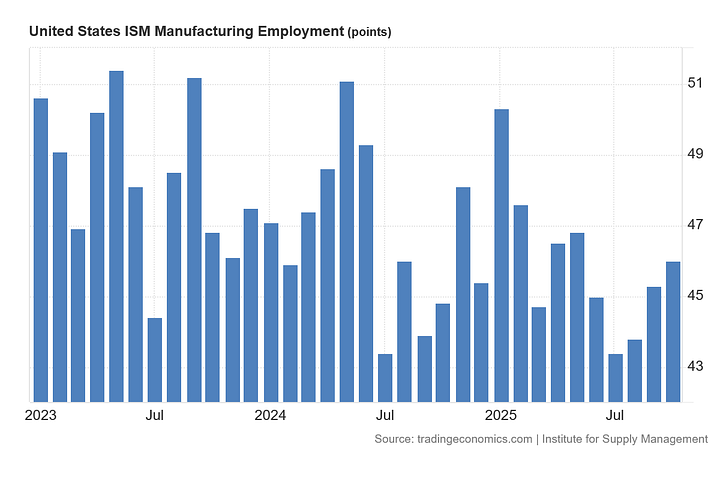

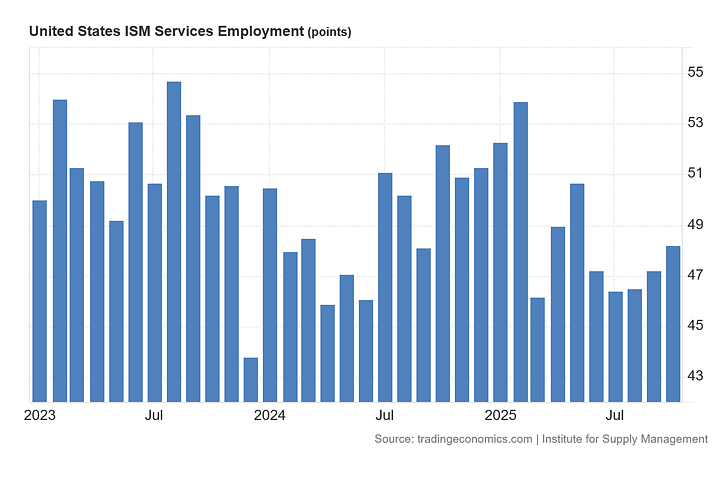

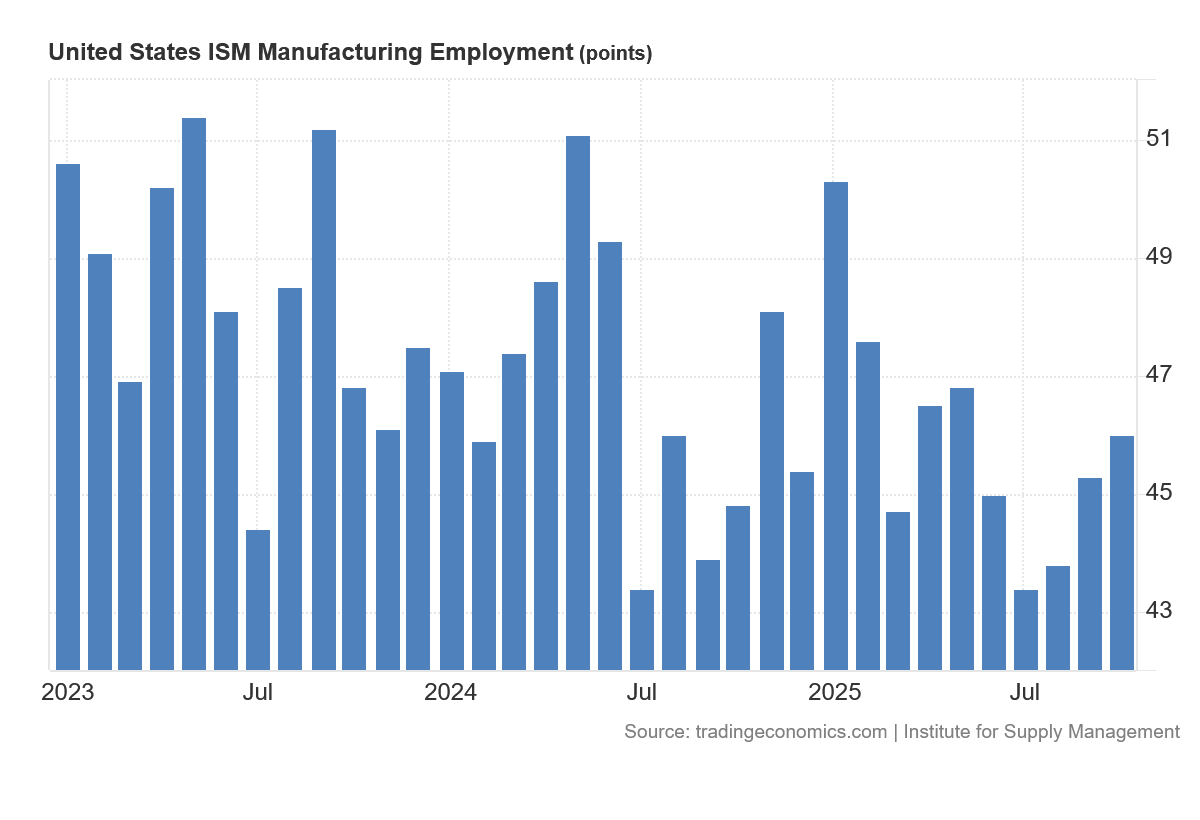

We see confirmation of the dysfunction in labor markets within the Institute for Supply Management’s Manufacturing Employment PMI and the Services Employment PMI, both of which have printed contraction—job loss—for the past several months.

If the Federal Reserve is supposed to be encouraging full employment, it has been doing a lousy job of it for the past few years.

A full percentage point reduction in the federal funds rate would dramatically lower the cost of capital for small businesses, many of which borrow based on the banking Prime Rate (which runs 3 percentage points above the federal funds rate). Expanding small business access to capital would be a spur to new investment and thus increased hiring—something this economy clearly needs to be increased.

We Need More Investment, Period

Even before we consider the employment benefits of increased investment, a cursory look at the data shows the economy needs to significantly increase business investment.

A point that was completely overlooked in the GDP data for the second quarter was the collapse in private investment, following a momentary spike in the first quarter.

Prior to 2025, investment as a contributor to GDP has been weak or negative.

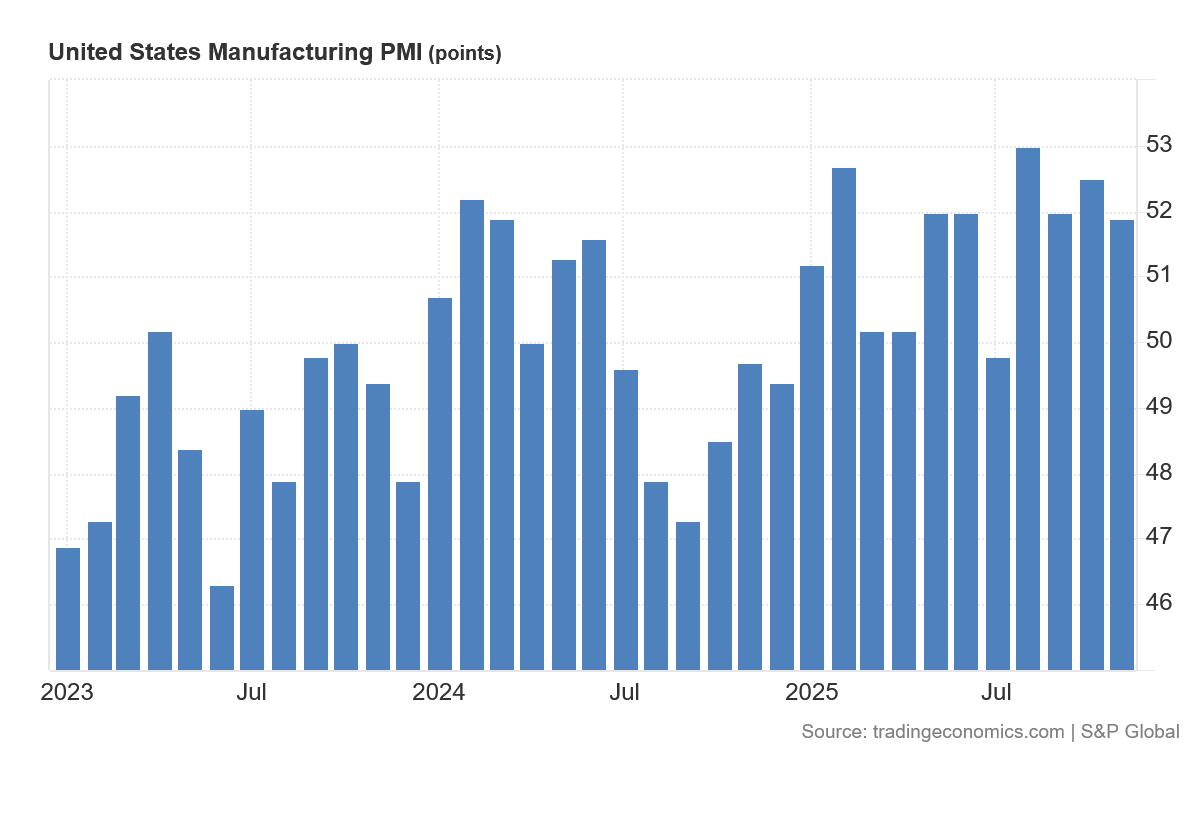

Again, the PMI data bears this out. The ISM Manufacturing PMI has been printing contraction almost non-stop for the past three years.

The S&P Global Manufacturing PMI generally trends higher than ISM, but even that has not shown consistent expansion since 2023.

Even the services PMI data from both ISM and S&P Global indicates uneven and uncertain expansion.

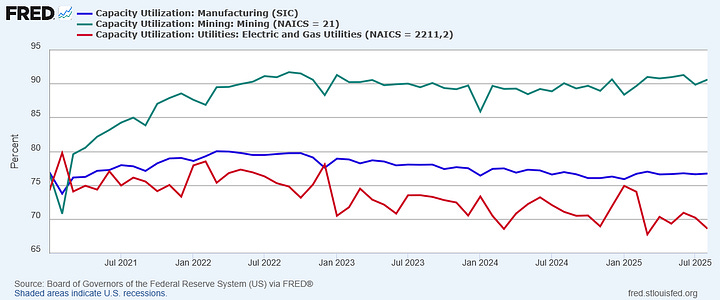

Across multiple sectors, capacity utilization in the US economy has either been stagnant or trended down.

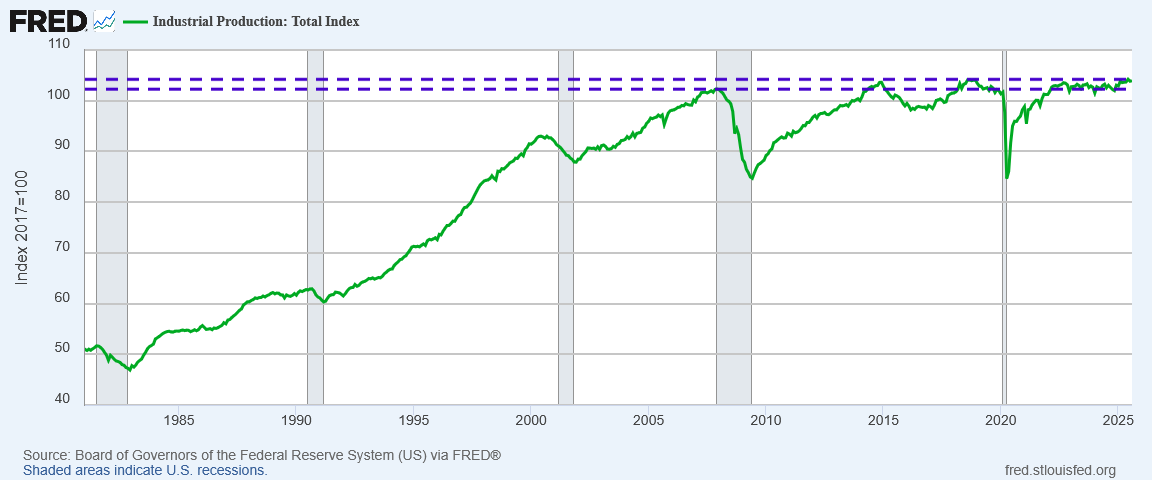

Even more concerning has been the inability for industrial production in this country to expand past certain levels, a ceiling that it has experienced since the mid-2010s.

For over ten years, and consistently since 2022, the Federal Reserve’s Industrial Production Total Index has remained mired in the same narrow band, not growing past that. Even the shakeups from the COVID Pandemic Panic were not sufficient to break industrial production in this country out of its doldrums.

Historically, prior to 2008 and the Great Financial Crisis, industrial production in this country has managed to grow fairly consistently, with only the occasional reversal.

Since 2008 that growth trend has all but stopped.

If President Trump is to deliver on his Agenda 47 goal of making the US a manufacturing superpower (a goal I wholeheartedly support), we must get industrial production back on a growth trend and not in this sideways trend of stagnation.

This sideways trend in industrial production is also yet another warning sign of stagflation for the US economy. That’s not a good thing.

“Too Late” Powell Has Ignored All Of This Data

There is a perverse irony in Jerome Powell and the Federal Reserve fretting about not having the latest CPI and jobs reports from the BLS, or the latest Personal Consumption Expenditures data from the BEA.

What difference would having those reports—covering only the single month of October—make when the Fed has blatantly ignored all of the foregoing data literally for years?

While the signs of liquidity stress in US financial markets are of recent origin, they are unmistakable and on their own call for a significant reduction in the federal funds rate. That was how Powell responded the last time there was this sort of liquidity stress. But for the advent of the COVID Pandemic Panic in 2020, that approach appeared to have at least ameliorated the funding stresses.

Rising jobless and the jobs recession are not of recent origin, having been fixtures of the US economy since 2023. “Too Late” Powell has ignored these trends all along. There is no reason to believe he would notice them should the BLS release an October jobs report.

Lack of growth in either capacity utilization or industrial production is yet another data trend to which Powell has remained doggedly oblivious. There is no way to tell if this oversight is a reflection of his incompetence or a reflection of his anti-Trump malice, but at this point that is a distinction without much difference.

Powell has publicly stated the Fed does look at all manner of public and private data sources, which means he should have been looking at all the metrics cited here. If he has been looking at these data sets, he has no clue what the data means. If he has not been looking at these data sets he’s lying through his teeth. Both possibilities lead us to exactly where we are now, with the Fed needing to make a significant rate reduction but unlikely to do more than make a 25bps cut.

The US economy is unquestionably heading into rough waters. We may even be heading into a repeat of the Great Financial Crisis. Significant Fed action is warranted here, if only to alter the trajectory of the economic and financial crises that appear to be developing. The Fed probably cannot prevent them at this point, but aggressive action on rates at least holds out a possibility of buffering some of the impact of these crises when they emerge.

It is clear from the data that an aggressive rate reduction should have been implemented earlier this year. Instead Powell dithered and delayed, and then proceeded with rate cuts that were too small to have the necessary effects. Powell has not only earned his moniker “Too Late”, he has earned the additional badge of dishonor “Too Little”.

Wall Street is currently betting that December will bring another 25bps rate reduction in the federal funds rate. Given Powell’s history of pandering to Wall Street expectations, I expect that will prove to be the FOMC’s decision.

It won’t be enough. The US economy needed a large cut earlier this year and it still needs a large cut now. Powell doesn’t want to give it and probably won’t, which means the US economy will be heading into 2026 in poor and deteriorating condition.

Jerome Powell’s final Christmas gift to the United States: deepening recession potentially spiraling into a depression.

Wow. The first half of this post literally put chills down my back. I just knew that the monstrous growth and power of the big private equity firms such as Blackrock would result in some kind of financial disaster. Not being a finance professional, I didn’t know how. But you’re putting the pieces of the picture together in ways that make sense - really scary sense!

Here in Minneapolis, there has been a local building and renovation firm, Rusco, in business for 70 years. Their TV commercials have been ubiquitous since I was a little kid. Well, a few years ago, they were acquired by a private equity firm, which in turn was acquired by Blackrock, and - long story short - Russo had to file for bankruptcy a few weeks ago. After 70 years! Everyone was stunned, the local media had to explain the financial shenanigans. I was left with a foreboding of bad economic effects - which you have just illuminated, and thank you for that, Peter. I think you’re onto something big!

https://www.startribune.com/how-a-private-equity-roll-up-sank-minnesota-rusco/601522505?utm_source=gift