As oil prices have climbed recently, I have repeatedly come to the conclusion that global benchmark prices would soon plateau and stabilize.

The oil price ceiling might wobble, and might even slide up to $88/bbl. It could even flirt with $90/bbl. However, as long as the prices are dependent upon constrained supply, the overarching trend in oil prices will remain downward. Unless demand firms up, the future of oil prices is always going to be lower and not higher.

As I have been concluding this, oil prices have been pushing higher and higher, in dogged determination to make mockery of my efforts at market prediction.

However, given that oil prices have been rising for the past several weeks, what is not a prediction is that oil prices will put renewed upward pressure on prices and reignite consumer price inflation.

Earlier this week, the International Energy Agency warned that oil markets were in a deficit that would deepen in the fourth quarter.

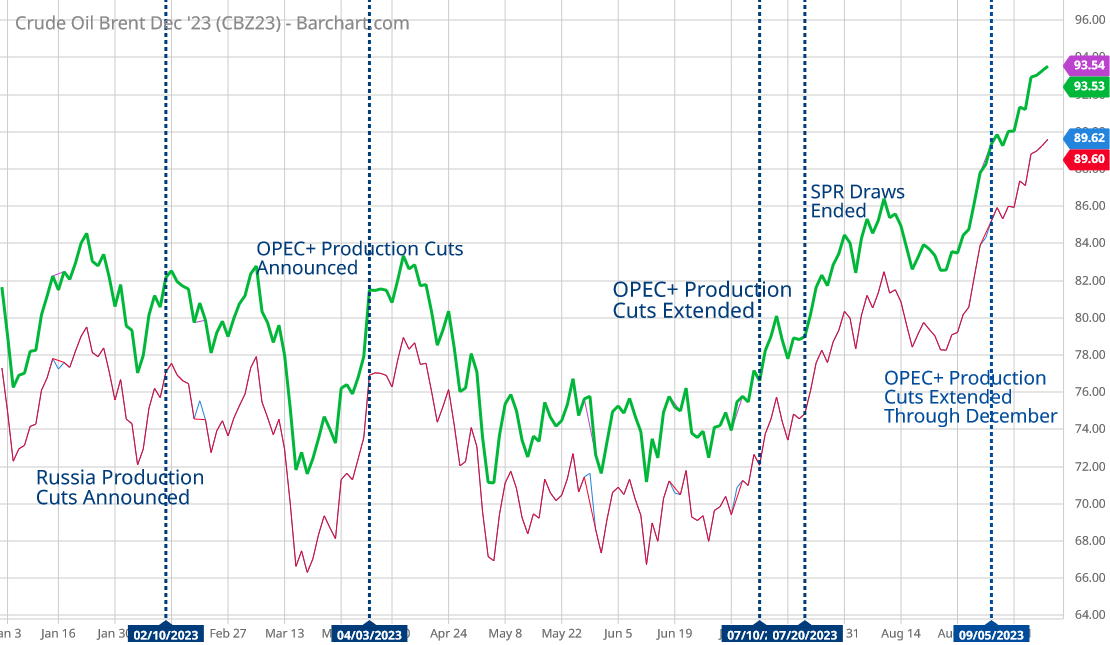

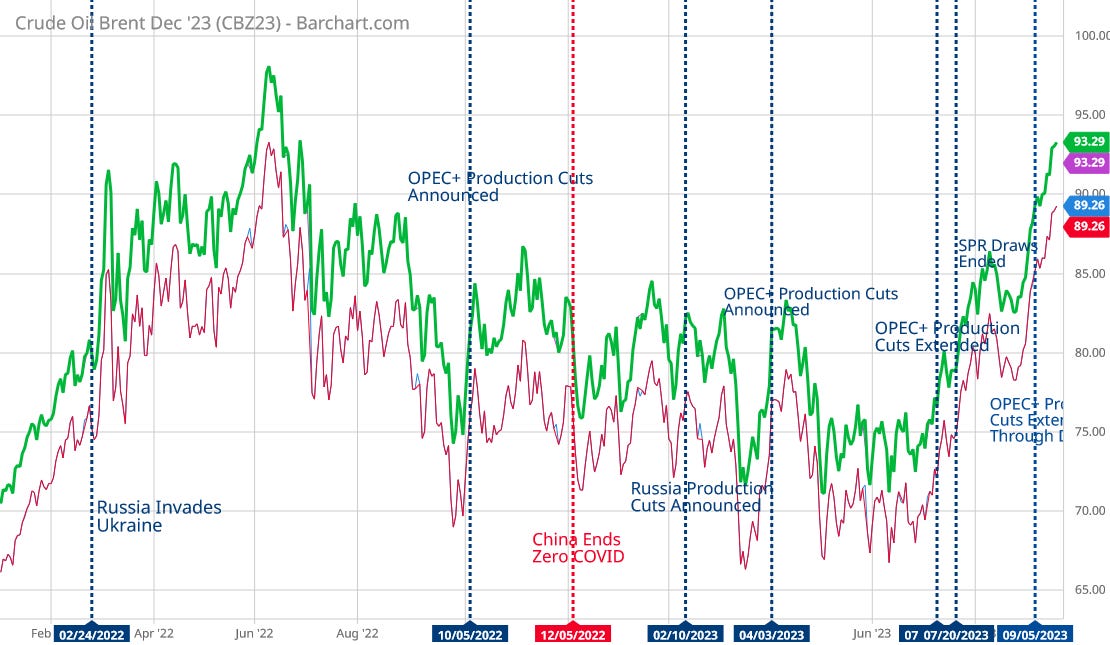

The reason? Saudi and Russian cuts that were just extended until the end of the year.

The deficit may yet deepen, but it is already causing pain to energy consumers and reigniting inflation. Just when central banks thought they'd got it under control.

As we have seen just here in the US, energy prices have stoked resurgent inflation.

How much higher can they go? What is finally pushing prices up after months of OPEC+ production cuts?

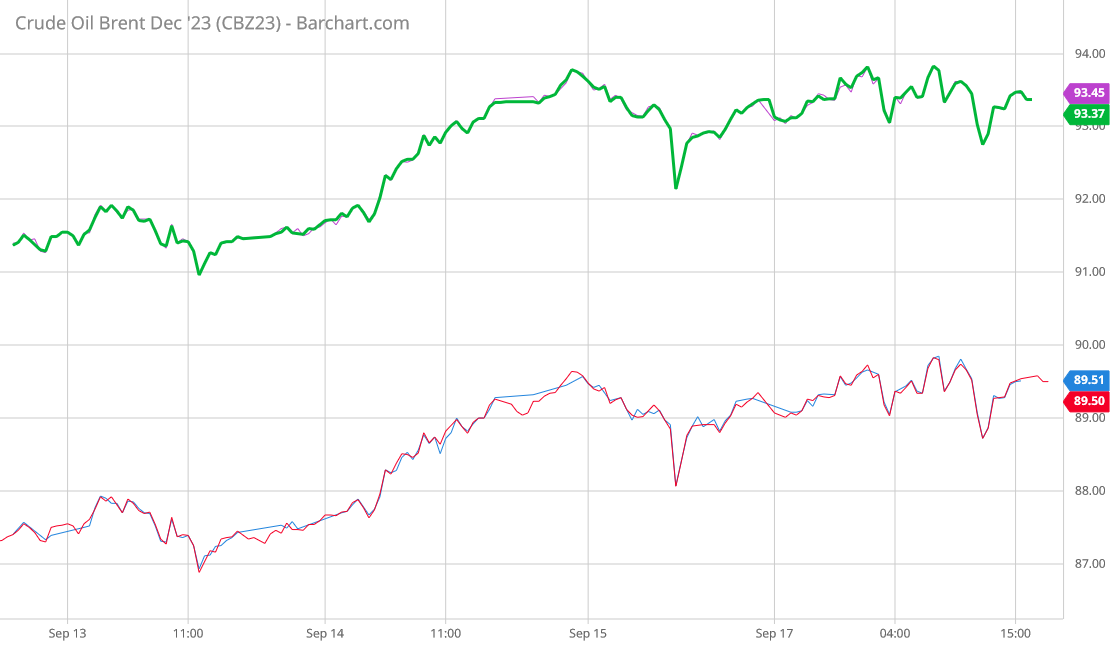

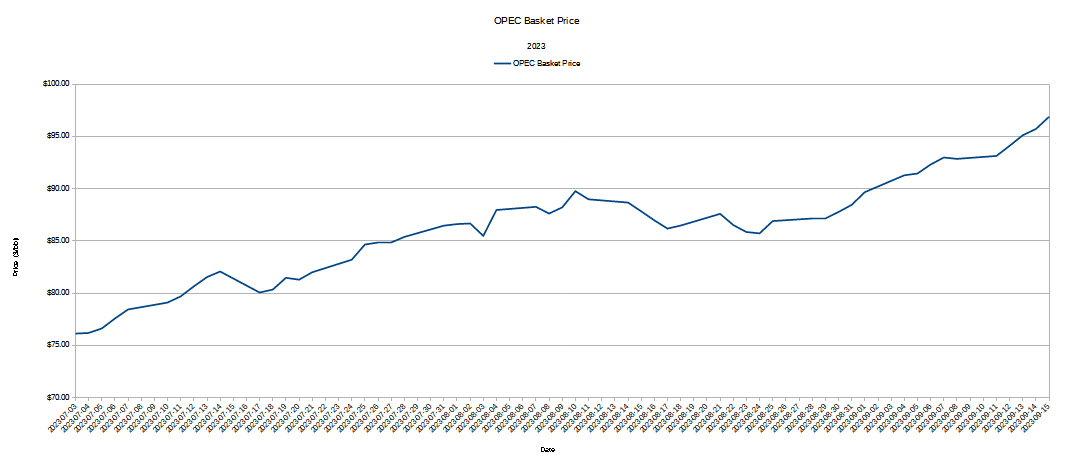

To be sure, if we look at the price of global oil benchmark Brent Crude over the past few days, we see that a price plateau had been reached.

From after-hours trading on September 14 through September 18, the price for Brent Crude had oscillated just north of $93/bbl.

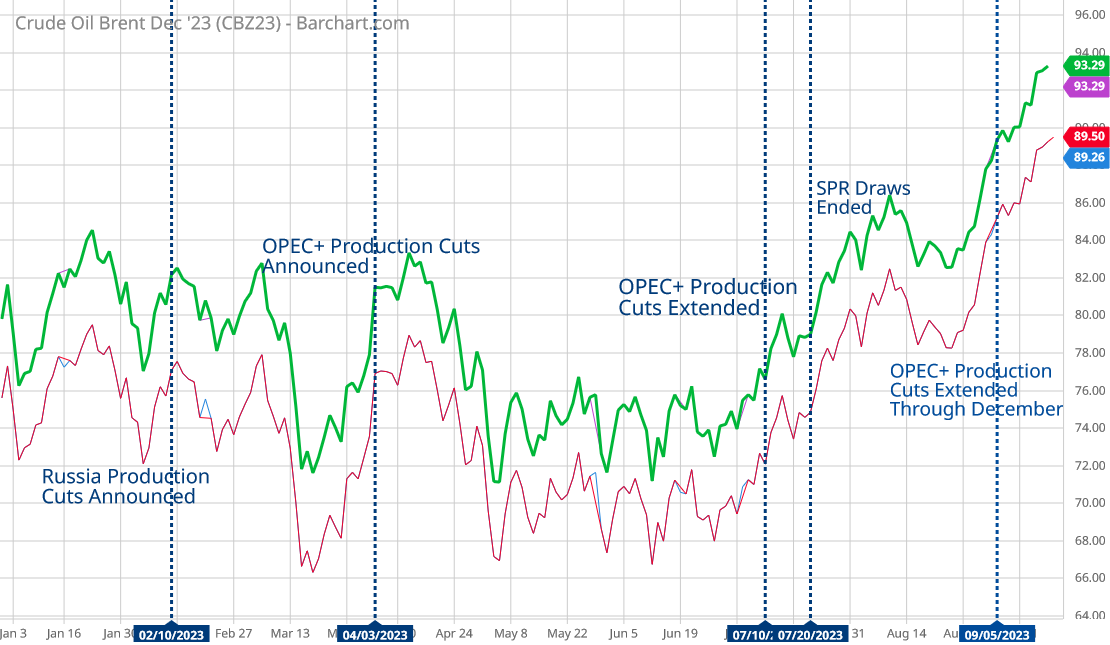

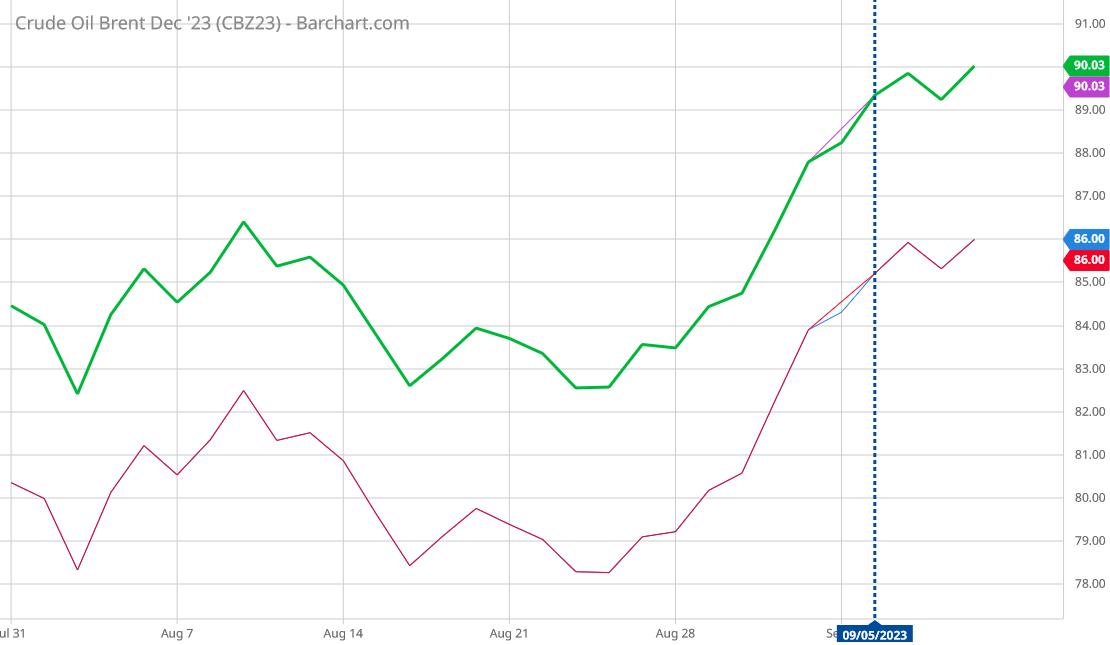

However, when we look at the daily closing price from the start of 2023 forward, we don’t see the same plateau effect.

Regardless of what the trends may appear to be day to day, over the longer term we are not seeing as of yet an extended price plateau for crude oil. If this longer term trend continues very much longer $100/bbl oil will be not just a possibility but a disturbingly real probability.

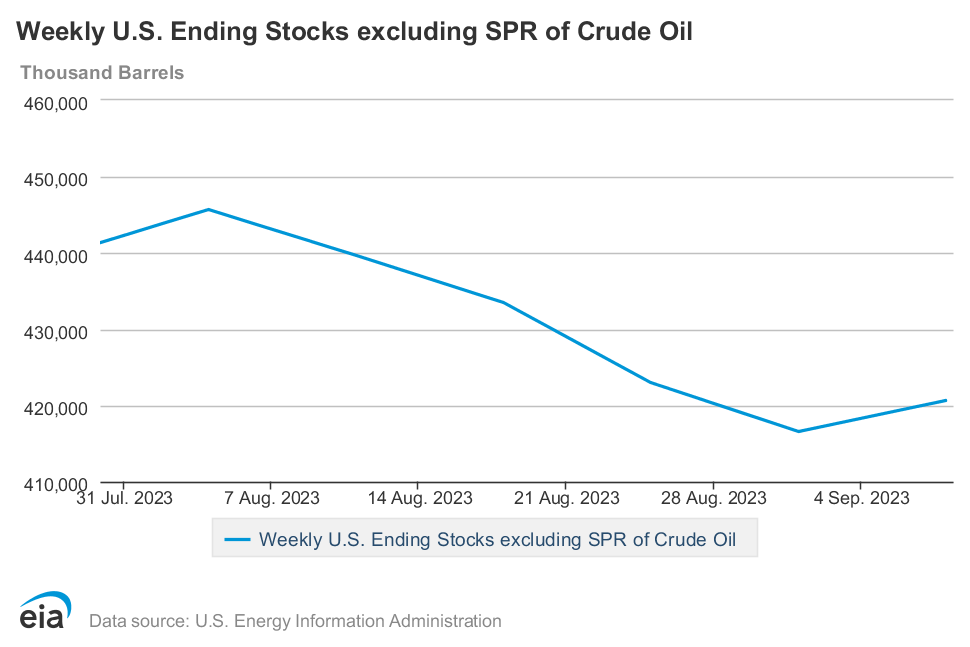

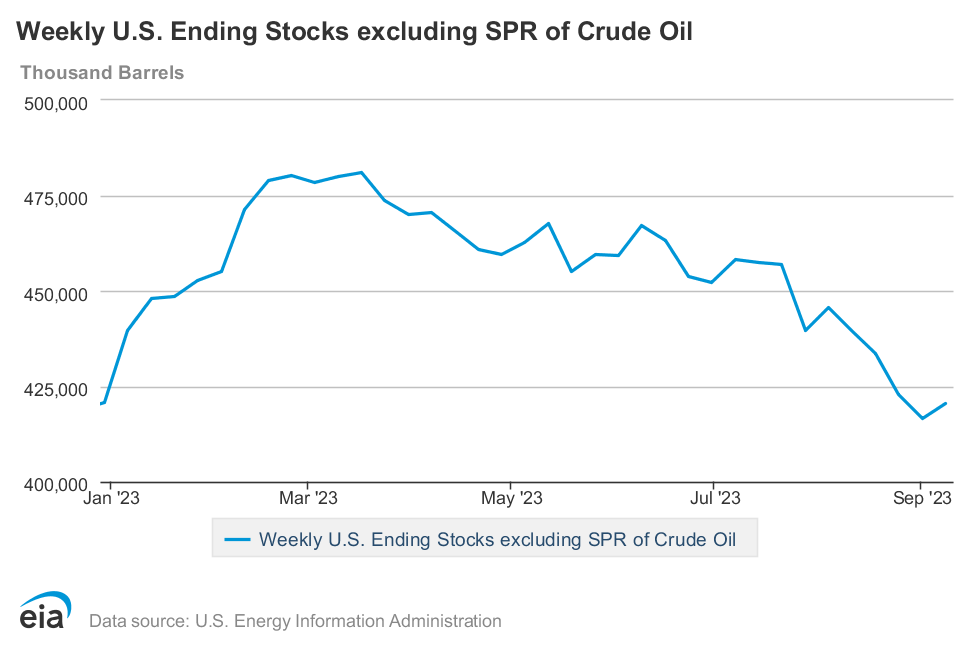

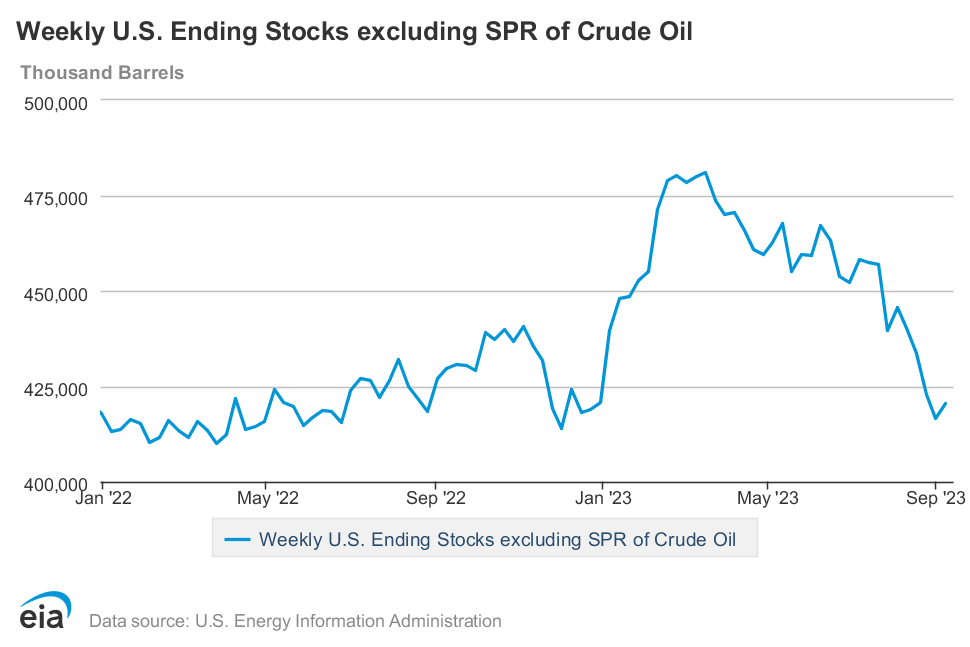

However, there is a curious conundrum surrounding the recent oil price rises: while price rises usually accompany drawdowns of oil stocks and price declines accompany builds of oil stocks, recently we have seen the inverse situations occur.

From August 4 through September 1, the Energy Information Administration showed oil stocks steadily declining week on week, and rising thereafter.

However, from August 7 through August 24, oil prices fell, only to rise thereafter.

This is the exact opposite of what we would expect to see. Rising oil stocks should not be correlated to rising prices.

When we look at a longer time frame, such as from the beginning of the year, we see a similar counterintuitive movement.

Oil stocks have been drawing down since March, yet oil prices did not begin seriously moving up until around June 27.

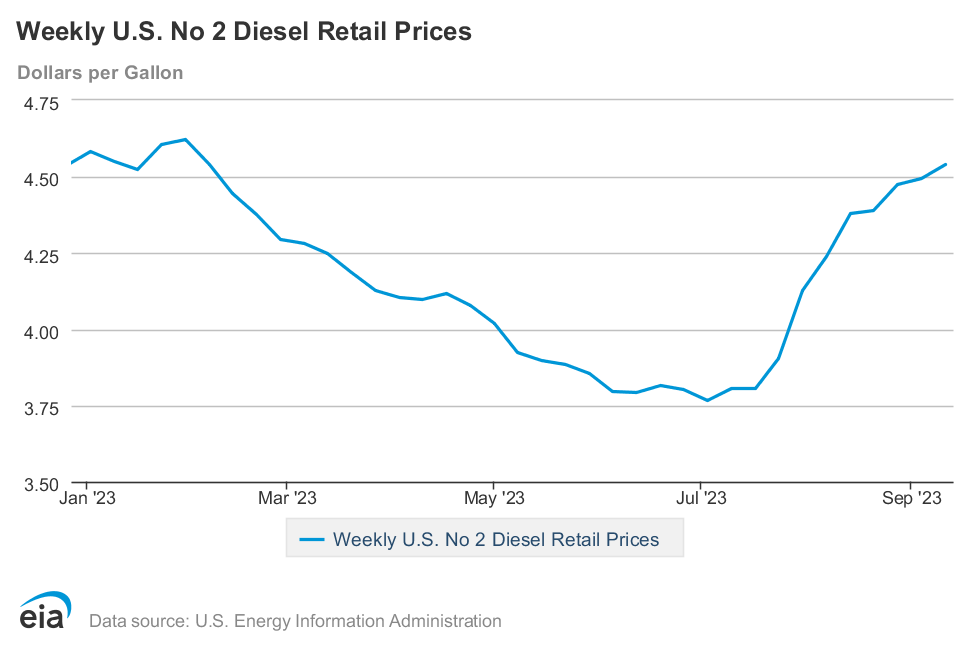

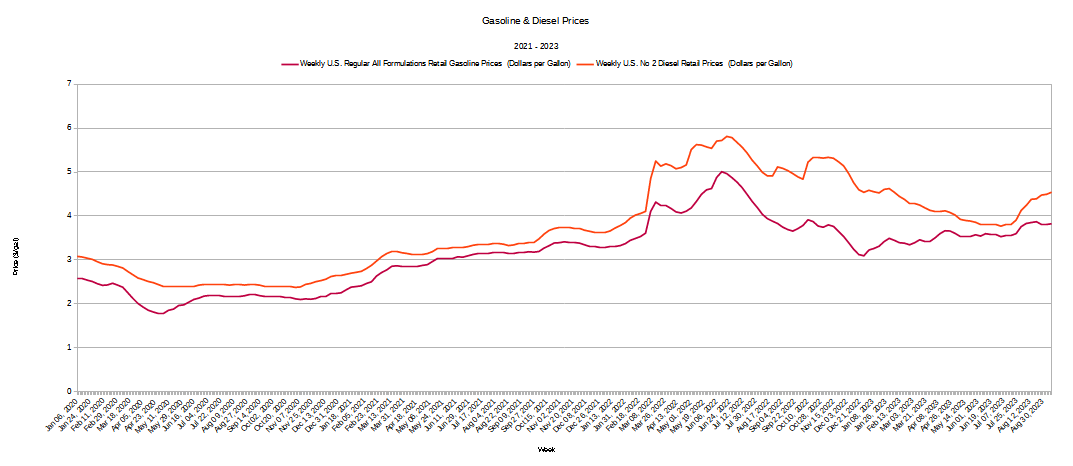

Crude oil prices are following similarly counterintuitive trends when viewed against other potential price pricessures as well. The rise in diesel prices, for example, has been lagging crude prices by only a few weeks.

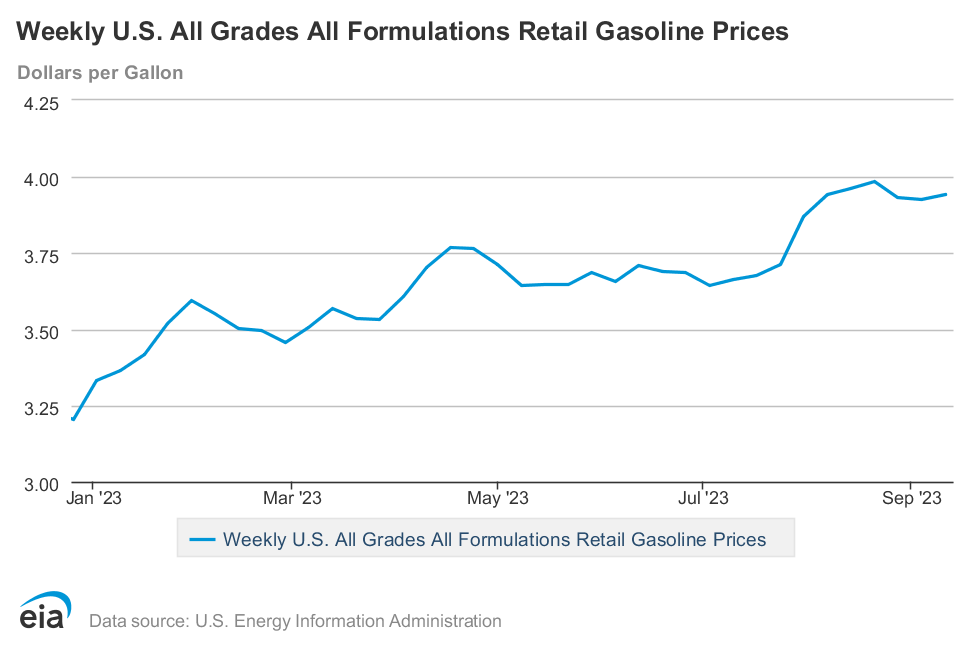

Meanwhile, gasoline prices have been moving up since the beginning of the year.

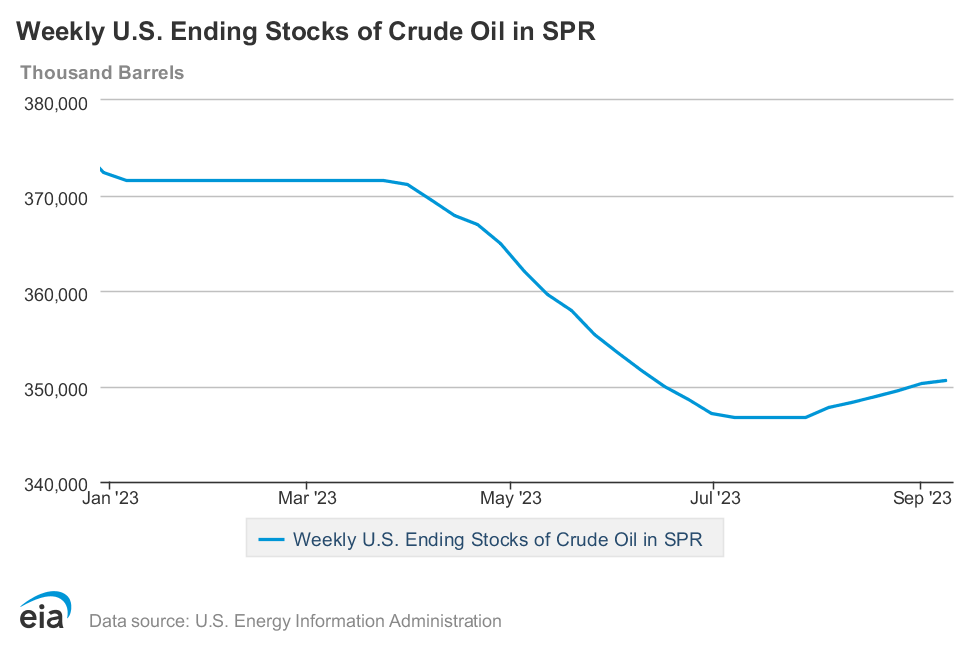

Perversely, even the slight rebuilding of the Strategic Petroleum Reserve has taken place not when prices were declining but rather when they were increasing.

These are not the price movements we would normally expect to see.

One concern that has been pushing price up has been a perceived lack of diesel fuel inventory.

Global inventories of middle distillates, including diesel, heating oil, and gasoil, are palpably lower than they usually are at this time of the year. On top of that, there is not enough refining capacity to remedy matters. Neither is there enough sour crude.

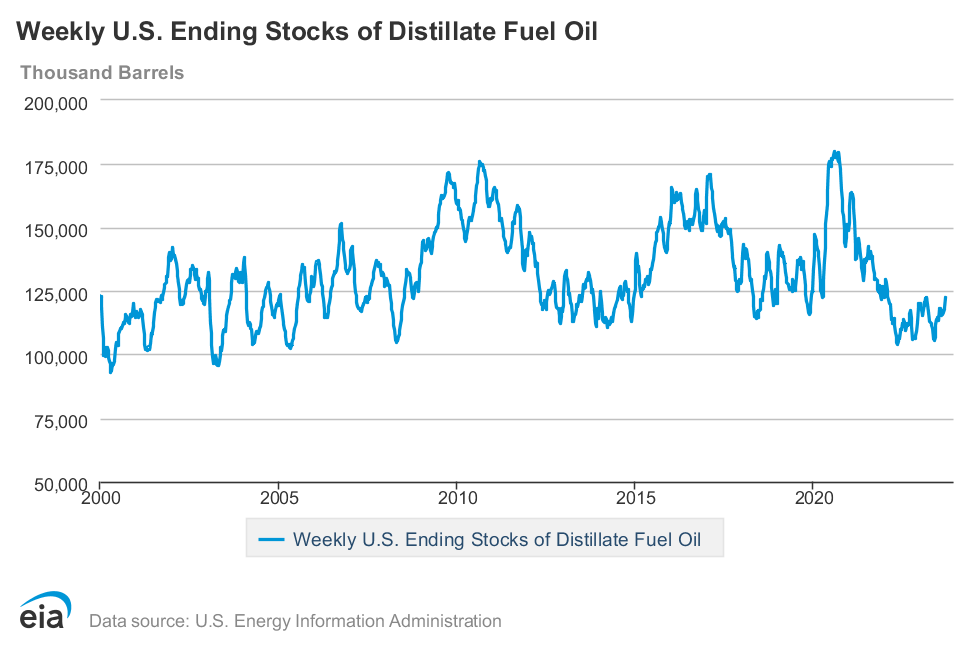

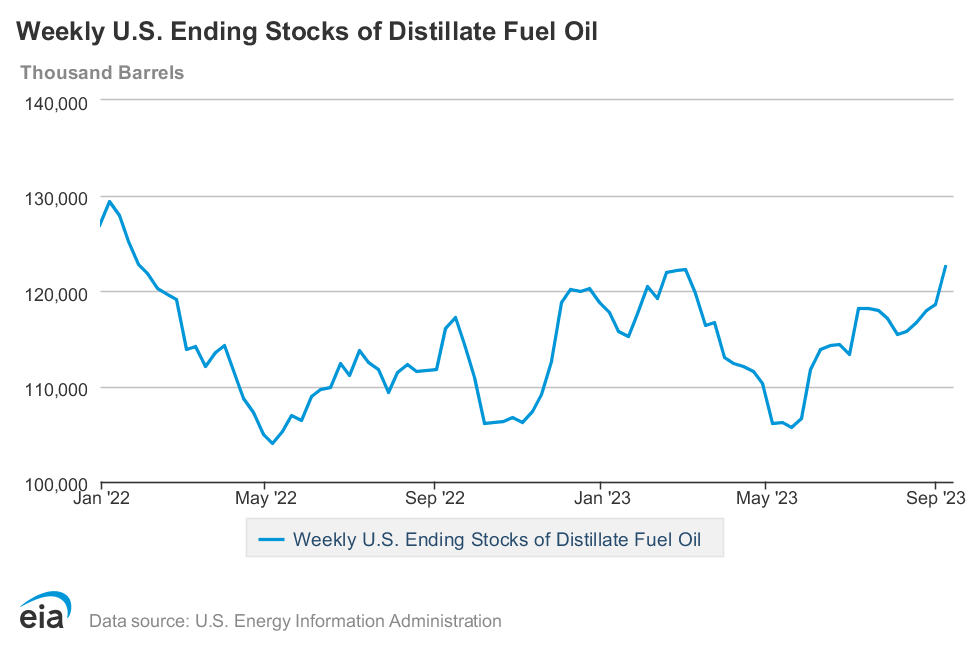

When we look at diesel inventories in the US going back to 2000, we do see that current inventories are on the low side of the range.

However, when we look more closely at inventory levels since the beginning of 2022, we see that current diesel stocks in the US are higher now than they were this time last year.

Yet despite having a larger inventory of diesel than last year, diesel is at a higher price than last year.

Even though diesel inventory should be providing a downward price pressure, we are not seeing much indication of that.

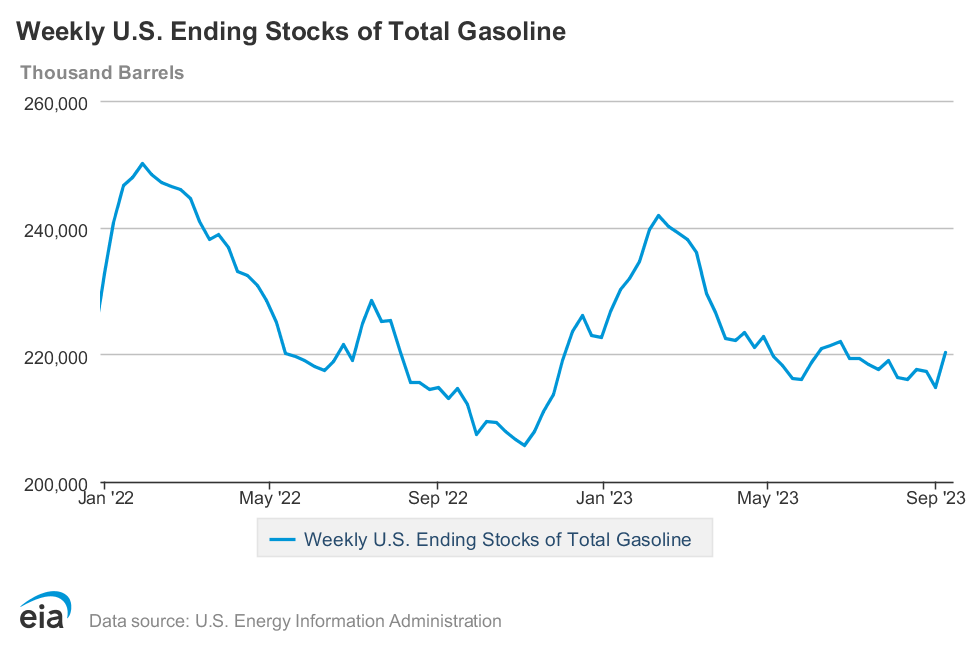

Similarly, gasoline inventories are higher now than they were last September.

Indeed, when we look at crude oil inventories in the US since the beginning of 2022, we see that they were higher when the prices rises began at the end of June than they were in June of 2022, and that only recently have the inventory drawdowns brought inventories down to the levels of this time last year.

These inventories should have buffered oil prices, but they appear not to have done so, at least not noticeably.

This is odd, because China’s oil inventories have been seen as providing a similar buffer against oil price surges.

"China built up the stocks to run them down when it wanted to avoid the overheated market of July-August," said Kpler analyst Viktor Katona.

"As a tactical move, it worked well because they've avoided the $85+ per barrel environment for large-scale purchases."

Adi Imsirovic, director at energy consultancy Surrey Clean Energy, estimated China bought about 750,000 to 1 million barrels bpd of crude just for storage in the first half of 2023.

"With prices at at least $85 and above, China will not buy for storage," he said.

"That will just cancel out what the Saudis are doing."

Why should China’s oil inventories buffer oil prices but not US inventories?

Ironically, diesel may itself be part of the answer to that question.

Not all crude oil blends are created equal. Diesel fuel and similar fractions are more plentiful in the heavier crudes which were targeted by Saudi Arabia and Russia for their production cuts.

Saudi Arabia's oil production cuts announced in the summer certainly aggravated the situation—the Saudis mostly cut heavier crude grades that are used to make middle distillates. So did Russian export cuts. But there was another reason why the world's middle distillate stocks are so much lower than normal: there are not enough refineries.

The problem is acute in Europe and North America, where a number of refineries were shut down during the pandemic, and others were converted to biofuel production plants. The remaining capacity appears to be sufficient for gasoline production in response to demand but not adequate for diesel fuel and other middle distillates demand.

Thus we are seeing the markets attempting to reprice not just current oil demand—which still has shifted less than the rise in crude oil price indicates—but also the challenges going forward in replenishing and maintaining diesel inventories. The price rises are less a reflection of overall demand for oil and more an anticipation of future scarcity specifically of Saudi Arabian crude, which will impact diesel fuel output.

This is one reason we have seen OPEC prices actually rise above Brent benchmark prices in recent days.

The OPEC and Russian oil production cuts are currently anticipated to have an outsized impact on diesel fuel production, thus Saudi crude in particular is now experiencing relatively stronger demand.

However, while rising prices for Saudi crude are driving up energy prices overall, they are also driving up consumer price inflation (because they are driving up energy price inflation).

That rising diesel prices have contributed to energy price inflation and helped reverse recent declines in year on year consumer price inflation is readily established by the timing of diesel prices.

When we look at weekly gasoline and diesel prices as recorded by the Energy Information Administration, it is immediately clear just how much these prices have risen during this cycle.

However, the sector where diesel prices most impact overall prices is construction, and that sector has plateaued in recent months.

One area where prices have definitively reached a plateau is construction. There, no one sub-category is dominant, with all more or less following the same general trajectory.

However, what all the various trajectories show is a price plateau beginning during last fall and continuing through last month.

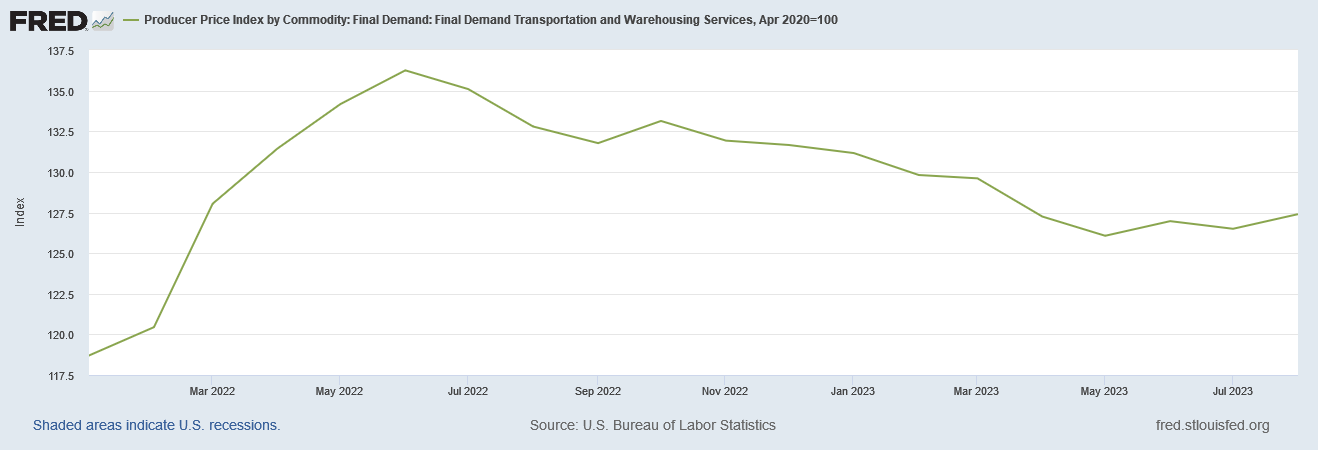

Even Transportation is experiencing lower levels of inflation than before, as evidenced by the Producer Price Index data.

Perversely, while demand for Saudi crude is helping to push up oil prices broadly, the impact of Saudi production cuts on diesel prices is producing an inflationary backlash in economic sectors which are highly dependent on diesel fuel to operate. Demand in construction and transportation, which are both showing signs of weakness, will limit how much of an upward price pressure the relative scarcity of Saudi crude (thanks to production cuts) can support.

Additionally, as prices rise, incentives for increased oil production from outside OPEC and Russia also rise. The upward price pressure is also an upward production pressure, and there are more oil producers than just OPEC and Russia.

Oil prices should ease as a result of an increase in supply from countries other than OPEC+ leaders Saudi Arabia and Russia, Citigroup Inc. said.

While technical traders and geopolitical risks may push prices over $100 for a short period, the extra supplies mean that “$90 prices look unsustainable,” analysts, including Ed Morse, wrote in a note. That should, in turn, reduce the price of key fuels such as gasoline and diesel.

Because of that upward production pressure, Citi analysts among others see oil trending back down during the fourth quarter of 2023 and beyond.

Citi's analysts see oil averaging $84 in the fourth quarter 2023 and moving to the low-$70 range in 2024.

Morse writes production is growing among non-OPEC+ members like the US, Brazil, Canada, and Guyana. Even Venezuelan and Iranian exports have grown.

"After the recent spike, these inventory dynamics should keep a lid on crude oil prices for the remainder of 2023 and 2024. And Saudi Arabia may yet reverse cuts if markets get too tight," said the note.

Thus while the OPEC production cuts have shifted some of the pricing equilibrium for various refined products, diesel in particular, they still are not being matched by organic demand pressures for those products. On the contrary, while there is global demand for oil, that demand has not increased much relative to supply.

Brent crude climbed toward $95 a barrel Monday as production cuts led by Saudi Arabia and Russia helped drain inventories at a time when global consumption has held firm. Premiums for physical barrels have also surged as refineries try to make the most of robust margins.

Regardless of how large the absolute demand for oil actually is, oil prices are set by the relative levels of demand against supply. If demand rises but supply rises more, prices overall for oil will fall.

OPEC made the production cuts largely in an effort to alter the relative levels of supply and demand for oil from the supply side. Since demand was not rising to meet supply, OPEC reduced supply to meet demand, with an eye towards establishing a higher equilibrium price for oil. After months of production cut rhetoric and finally action, those efforts began to be successful at the end of June.

Thus, oil markets are, at present, repricing and moving towards that new equilibrium price for oil.

Without fresh organic demand pressures, the current production levels will still result in a new plateau being reached in the relatively near future. The OPEC production cuts are already set, and that means that future supply as well as current supply are reliably known quantities. This in turn means that inputs for the production of various fuels such as diesel are also reliably known quantities. With higher oil prices bringing in more oil production and delivery from outside OPEC and Russia, it is most likely that current market estimates of future supply will tend to underestimate the amount of future supply.

Without an organic increase in demand for those fuels, the recently and artificially created scarcity of specific crudes (and thus specific inputs for specific fuels and refined products) will thus have a finite influence on rising oil prices. Moreover, as the prices for both the crudes and the refined products rise, demand for those refined products will be further constrained. Thus the near term outlook for oil almost certainly is one of limited upside followed by an extended downside.

Oil prices may show some additional increases over the near term, but oil prices are still likely to stabilize within a particular price range over that same near term. After they stabilize, the steadily deteriorating global economy will once again begin to pull oil prices back down again.

Could there be some unknown factor at play in this? Likely raw supply, which some are saying there may be a ceiling that we are not estimating correctly. Just a thought.

Speaking on a personal level, I averaged 51.2 mpg in the Audi, taking the girls to school. Where this is a good mpg figure, it almost killed me to drive like the grandpaw I am!