Who's The Outlier?

Neither The Fed Nor Any Other Central Bank Is Able To Push A String

On Wednesday I described the European Central Bank’s decision to raise their key bank rates 25bps as the ECB “breaking ranks” with the Federal Reserve.

However, as more central banks are making interest rate decisions, it appears that the Federal Reserve is the one who has broken ranks with the rest of the world’s central banks, opting for a “pause” while the other banks press on with raising rates.

So who’s got it right?

As I discussed previously, the ECB raised its key bank rates 25bps the day after the Federal Reserve opted to hold the federal funds rate at its current level.

Inflation has been coming down but is projected to remain too high for too long. The Governing Council is determined to ensure that inflation returns to its 2% medium-term target in a timely manner. It therefore today decided to raise the three key ECB interest rates by 25 basis points.

While this was met largely with indifference by equity markets in Europe, in the days immediately following the rate hike announcement Europe’s long-term sovereign debt yields actually declined, while short term yields barely moved upward.

European financial markets heard the ECB rate hike announcement and basically said “Meh”.

Yesterday, the ECB was joined by the Bank of England, which surprised the markets by making a 50bps hike to its Bank Rate instead of the 25bps the markets had been expecting.

The Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) sets monetary policy to meet the 2% inflation target, and in a way that helps to sustain growth and employment. At its meeting ending on 21 June 2023, the MPC voted by a majority of 7–2 to increase Bank Rate by 0.5 percentage points, to 5%. Two members preferred to maintain Bank Rate at 4.5%.

At the time of the previous MPC meeting and May Monetary Policy Report, the market-implied path for Bank Rate averaged just over 4% over the next three years. Since then, gilt yields have risen materially, particularly at shorter maturities, now suggesting a path for Bank Rate that averages around 5½%. Mortgage rates have also risen notably. The sterling effective exchange rate has appreciated further.

The BoE was joined by Norges Bank, the central bank of Norway.

Norges Bank's Monetary Policy and Financial Stability Committee decided to raise the policy rate by 0.50 percentage point to 3.75 percent. The Committee’s current assessment of the outlook and balance of risks implies that the policy rate will most likely be raised further in August.

Even Turkey’s central bank jumped on the bandwagon, opting to nearly double its key bank rate.

The Monetary Policy Committee (the Committee) has decided to increase the policy rate (the one-week repo auction rate) from 8.5 percent to 15 percent.

By comparison, the Swiss Central Bank’s decision to raise its key rates by 25bps seemed rather muted on the day.

The SNB is tightening its monetary policy further and is raising the SNB policy rate by 0.25 percentage points to 1.75%. In doing so, it is countering inflationary pressure, which has increased again over the medium term. It cannot be ruled out that additional rises in the SNB policy rate will be necessary to ensure price stability over the medium term. To provide appropriate monetary conditions, the SNB also remains willing to be active in the foreign exchange market as necessary. In the current environment, the focus is on selling foreign currency.

Not only were central banks raising rates, they were indicating there were more rate hikes still to come.

Suddenly the Federal Reserve seems no longer the trend setter among central banks.

To be sure, the Federal Reserve is not entirely out of sync with other central banks, as in his testimony before Congress on Wednesday Jay Powell reiterated the Fed’s stance that further federal funds rate hikes will be forthcoming.

In light of how far we have come in tightening policy, the uncertain lags with which monetary policy affects the economy, and potential headwinds from credit tightening, the FOMC decided last week to maintain the target range for the federal funds rate at 5 to 5-1/4 percent and to continue the process of significantly reducing our securities holdings. Nearly all FOMC participants expect that it will be appropriate to raise interest rates somewhat further by the end of the year.

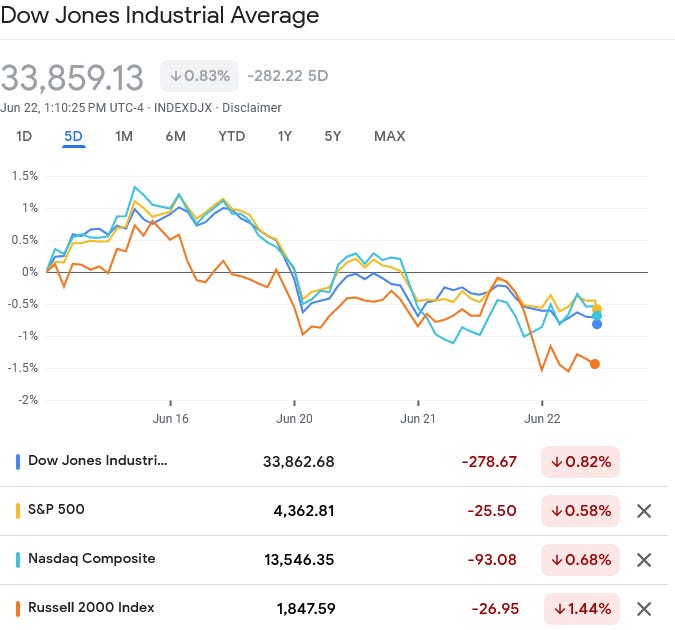

It is perhaps unsurprising, therefore, that global equity markets have not exactly been pleased with these latest central bank moves.

Europe’s stock markets have been trending down all week.

While China’s stock markets had been trending slightly positive for the week, that reversed as the Fed and the european central banks reiterated a continuing policy of interest rate increases for the near term.

Japan’s markets moved largely sideways.

Meanwhile, the US stock markets have been trending negative for most of the week.

Europe’s bond markets have been somewhat more responsive to the rate hikes, with short term yields moving up in several countries, including Great Britain and Norway.

British Gilts and Norwegian debt in particular had significant response to the rate hike announcements, with both countries 3-month sovereign debt yield moving positive on the week.

As has become something of a pattern, longer term maturities had a somewhat different response, with British Gilts in particular declining on the heels of the BoE announcement, and even Norwegian 10-year debt dropping somewhat after rising for the week.

Market analysts globally are continuing to press their case that continued rate hikes by central banks place the global economy in danger of recession.

Central banks are supposed to be trusted guardians to promote the right conditions for sustainable growth and financial stability, but are they taking needless risks in their haste to drive down inflation? The undue speed at which global interest rates have been ramped up in the past year suggests they are turning a blind eye to global growth hitting the skids again.

However, it is important to note that the markets longer term reactions to the rate hikes has been far less significant that the op-ed pieces discussing them tend to suggest.

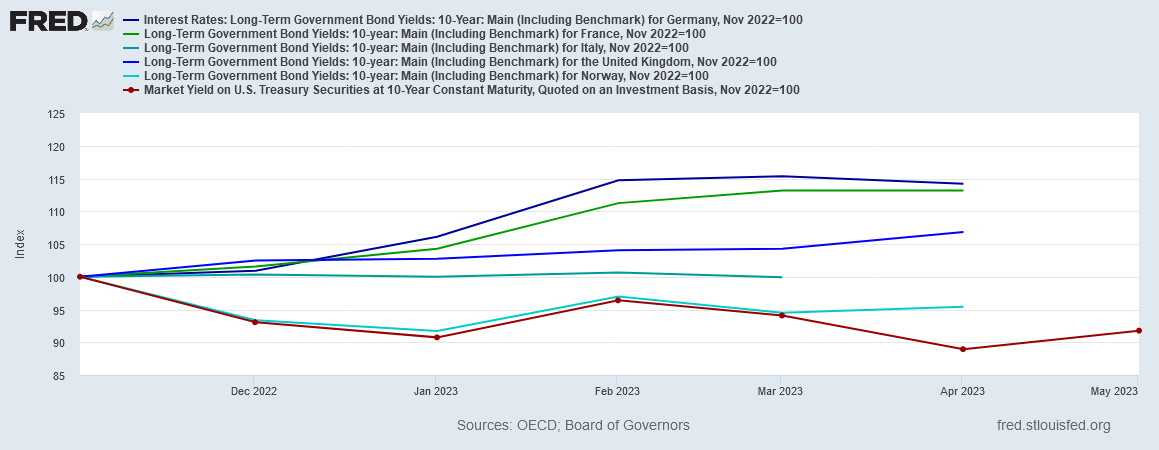

Particularly as regards long-term debt yields, a plateau was reached last fall and financial markets have not seen fit to push debt yields past it.

If we index the rise in yields to March of last year (when the Fed began raising rates), we see that in multiple countries interest rates largely stopped rising.

While in Germany and France, yields have risen somewhat over the past six months, in the US and Norway, yields have actually declined relative to where they were in November, 2022.

What I observed two months ago about the impotence of central banks when it comes to influencing market interest rates is still very much the case today. Central banks are raising rates, markets are largely ignoring them.

The less responsive market rates are to central bank manipulations, the more muted the impact central banks can have on the overall economy.

Viewed in this perspective, it may very well be that the Fed has realized that further rate hikes now will simply not have any good impact. The Fed may be the first central bank to realize that a pause was a better response than yet another rate hike, just as the Fed was the first major central bank to respond to inflation by raising rates.

The Fed may be for now the outlier when it comes to central bank rate hike strategies and inflation. However, all banks are still very much in the same crisis of impotency. Their efforts to nudge inflation down by nudging interest rates up are largely not working. In every country, and for every central bank, the same basic truth still holds: you can’t push a string.

I love your analogy of ‘you can’t push a string’. And I get the sense that the central banks are just muddling their way through things - impotent indeed.

But what’s up with Turkey, jumping their rate to 15%? Is that normal for them, or a reflection on their recent election results, or is their economy becoming increasingly nervous about their geopolitical location?

This shows the limits of what central banks can actually do with respect to the economy. Their God-like power apparently isn't so God-like after all, as evident in the relatively diffident response of the markets to the central banks' actions.