Last week, Wall Street was decidedly nonplussed when the Fed opted not to raise rates at the latest FOMC meeting.

The very next day, the European Central Bank opted to raise its key interest rates yet again, breaking ranks with the Federal Reserve.

The Governing Council decided to raise the three key ECB interest rates by 25 basis points. Accordingly, the interest rate on the main refinancing operations and the interest rates on the marginal lending facility and the deposit facility will be increased to 4.00%, 4.25% and 3.50% respectively, with effect from 21 June 2023.

Stock markets in Europe have had a similar tepid response to the ECB rate hike as Wall Street had to the Fed’s pause, with the major indices largely moving sideways in the days following.

With the Fed and the ECB having largely mirrored each other’s rate strategies for the past year, what do we make of the ECB’s breaking ranks now? Are the two central banks diverging on inflation fighting strategies?

The European Central Bank is not alone in continuing to raise interest rates despite the Fed’s pressing the “pause” button on the strategy. The Bank of England is widely expected to also raise interest rates tomorrow.

The Bank of England looks set to raise interest rates by a quarter point to a 15-year high of 4.75% on June 22, its 13th straight rate rise as it fights unexpectedly sticky inflation that risks making it a global outlier.

What makes these interest rate hikes particularly intriguing is that the European Union and the United Kingdom are both confronting softening economies with worsening economic outlooks, just as is the Fed here in the United States.

In the EU economic ministers are grappling with a persistent loss of economic confidence.

The economic mood in the euro zone clouded over more than expected in May. The business climate barometer fell 2.5 points to 96.5 points, according to data released by the European Commission on Tuesday. Economists polled by Reuters had only expected a decline to 98.9 points.

Industrial confidence slipped for the fourth straight month. The mood among service providers and retailers also went downhill. In the construction industry it clouded over slightly, while consumer sentiment brightened.

At the same time, the UK is barely growing, with the economy nearly flatlining in recent months.

Britain's economy grew by 0.2% month-on-month in April, the Office for National Statistics said, matching the consensus in a Reuters poll of economists.

Financial markets showed little reaction to the figures - in contrast to recent labour market and inflation data which boosted expectations for higher interest rates from the Bank of England.

Wednesday's data chimed with business surveys that point to weak activity - but no recession which had been widely predicted only a few months ago.

Over the three months to April, Britain's economy expanded just 0.1% - a "low growth trajectory" according to the British Chambers of Commerce.

Given that both the eurozone and the UK are experiencing the same struggles as the US to rein in inflation while not pushing their respective economies further into recession, one has to wonder why the ECB chose to break away from the Fed on interest rates—and why the BoE is likely to do the same thing on Thursday.

The global economic picture is further muddled given that last week China trimmed its seven-day reverse repurchase rate in an effort to boost liquidity and revive its moribund economy.

China’s central bank on Tuesday made a surprise cut to one of its key lending rates in a bid to shore up sputtering growth in the world’s second largest economy.

The cut to the 7-day reverse repo rate — the first since August last year — will boost liquidity in the banking system and make short term loans cheaper. The rate will drop to 1.9% from 2%, according to the People’s Bank of China.

The Fed has put its interest rate strategy in “neutral”, the PBOC is lowering interest rates, yet the ECB and very likely the BoE are raising rates. To the extent that central bank monetary policies have been coordinated recently, that coordination appears to be being abandoned.

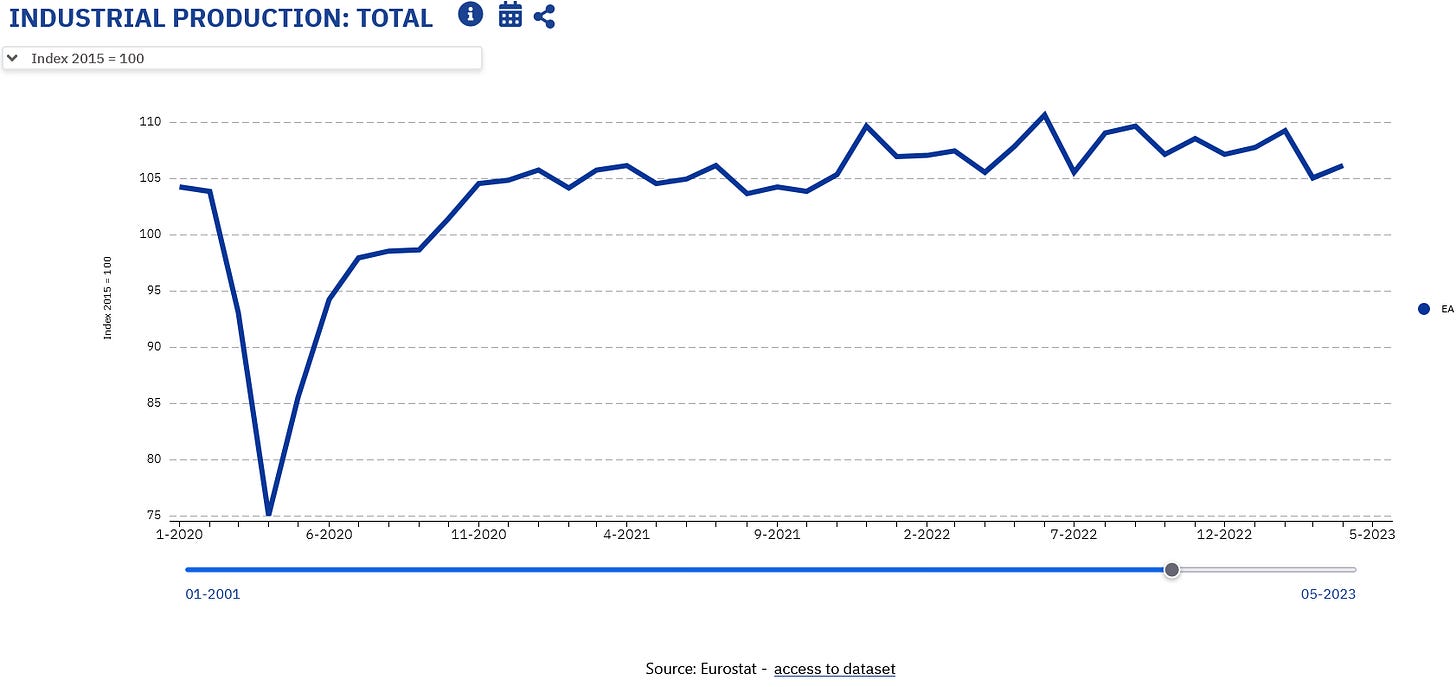

One reason the ECB may feel comfortable with continuing to raise its key interest rates is that, at least outwardly, aggregate euro area industrial production is still expanding, albeit somewhat slowly.

However, this may just be a difference in perspective, as US industrial production has recovered from the goverment-ordered 2020 recession in similar and at most only slightly less fashion.

Fathoming the ECB’s logic is even more difficult when one looks at the industrial production levels in the eurozone’s four largest economies. Germany, for example, hasn’t even gotten their industrial production back to pre-pandemic levels.

Germany and Spain are also in outright Producer Price deflation on intermediate goods, when viewed year on year, with France and Italy not far behind (and leading the rest of the eurozone into that same industrial stagnation we see unfolding in Europe..

At first glance, Europe’s economy looks very much like one that would benefit from interest rate reductions as the classical means to stimulate industrial production and have that stimulus reverberate throughout the economy. The ECB, however, reached a different conclusion.

On the consumer side, the eurozone as a whole as well as many of the individual economies are grappling with inflation that is significantly higher than what we have here in the United States.

Housing prices, while starting to decline, have still significantly increased in since the 2020 recession.

While much of the eurozone economy is clearly stagnant if not contracting outright, there are also major concerns regarding inflation yet remaining. Volker’s ostensible “success” in taming the inflation of the late 1970s with draconian interest rate hikes is still considered economic orthodoxy even among ECB economists. For better or worse, their formulaic response to inflation is the same as the Fed’s formula: hike the central bank interest rates and hope the market rates follow along.

In Europe, as in the US, that hope has been somewhat problematic. For short term yields it has been more or less met, as the 2-Year yield for the German Bund has risen slightly since the ECB raised its rates.

French and Italian 2-Year yields have largely followed along.

Yields on 10-Year debt, however, have actually declined since the ECB raised rates:

This is, readers may recall, not a new trend, as the influence the ECB has had over market interest rates has declined with successive rate increases just as has been the case with the Federal Reserve.

With this last rate hike, the ECB’s growing impotency over long-term yields has merely been reaffirmed.

Why did the ECB opt to continue hiking rates? Certainly the fact that Europe’s inflation rates are higher than in the US is a likely factor, as is the fact that European 2-year debt yields are not at all close to the year-on-year consumer price inflation rate, a reality which gives the Federal Reserve at least some cover for hitting the pause button on the rate hike strategy. In all other regards, the ECB is as much trapped into the prevailing narrative that central banks can control market interest rates by manipulating central bank interest rates—a narrative that time and again proves to be not completely true.

Europe, just as in the US, is showing signs of an increasingly stagnant and moribund economy, one in which deflationary forces are increasingly making their presence felt. Manufacturing in Europe in particular has not at all thrived over the past year.

Yet the ECB remains completely oblivious to the data regarding the state of the European economy. Perhaps even more so than the Fed, it is trapped into a narrative that says so long as consumer price inflation is high, the central bank shall keep pushing interest rates higher. That the markets have already reached a point where they no longer follow the lead of the central bank has not altered the ECB’s rate strategy.

Was the ECB right to raise its key interest rates? Certainly their move was the one dictated by the narrative. Yet the diffident response of bond and equity markets to the rate hike suggests European financial markets are not entirely confident in the ECB’s decision.

However, even if the ECB had not raised interest rates, Europe would still be stuck on the horns of a growing stagflationary dilemma: inflation remains high on the one hand, and the economy remains stagnant and sclerotic on the other. Europe is no more able to push the economic string than either the US or China; both markets and the overall economy move as they will, without regard to what the central bank either does or wants.

The ECB might want to believe it is choosing to go its own way by not following the Federal Reserve and pausing before pushing more rate hikes through. The reality is far more likely to be that the European economy is just slipping away, and the ECB has little to no power to prevent it.

Would ‘politics’ be the answer to this mystery? I know that the Fed is ‘supposed’ to be apolitical, but maybe in Europe there is even more pressure on the ECB to bend to political will. I don’t know. The financial markets don’t care much about political correctness, but maybe the ECB is pressured to make policy changes regardless of financial reality. What do you think, Mr. Kust?

I think they Fed and the ECB are all just floundering. Not knowing what to do and hoping this crisis somehow passes and the citizens of the west do not notice how incompetent and corrupt these institutions have become. I'd like to think the Fed or ECB are making policy based on thoughtful analysis, but I find this doubtful given where we are. Simply put, these people have way too much impact on our economy given their track record.