Yes, Virginia, Inflation IS A Crisis

The "Experts" And The Media Are Simply Wrong About Inflation

Our latest example of how horribly off-base the mainstream media can be on topics that genuinely matter comes courtesy of MSNBC columnist James Surowiecki, who either through naivete or simple ignorance portrays the rising inflation taking place in the US as well as the global economy as a net positive rather than a crisis.

At the same time, any discussion of inflation needs to include the context in which it’s happening. Historically, recessions have left Americans poorer, not better off. But the Covid recession was different. As people shifting their habits drastically in response to the pandemic, they spent much less and saved more. Even though millions of Americans lost their jobs, enhanced unemployment benefits and stimulus payments left many of them better off, not worse. And the stock market, after initially falling, boomed.

Just in case one misses Surowiecki’s point, he restates it further on:

What all this means is that American consumers are, relatively speaking, flush, and it’s that strong demand for goods and services that is sending prices higher. But it’s taking manufacturers and food producers time to increase supply after cutting back production during the pandemic. When you have high demand, and relatively low supply, prices go up. The inflation we’re seeing is not, then, some mysterious affliction that’s descended on the economy. It’s the predictable product of the economy’s rapid recovery, and its costs have been offset, to a large degree, by robust wage growth and government policies.

In other words, the economy is booming and that is driving prices up.

It would be nice if that were true. What a wonderful world it would be where that was the case. Unfortunately, it is not true, nor has it ever been true.

Inflation is not a benign consequence of economic growth, but is in fact a drag on economic growth. It is a burden, and never a benefit.

Falling Down The Rabbit Hole: I Have Said This Before

Those who follow my writings and ramblings know that I have argued this point before, highlighting how Federal Reserve monetary policy has succeeded only in obscuring an ongoing economic decline in the United States. That aspect of the inflation discussion has not shifted, but what Surowiecki’s MSNBC piece illustrates is the extent to which the prevailing narratives on inflation and the economy are simply not true.

Jeffrey Schulze, writing in Forbes, argues that the inflation we are seeing now is but a temporary “transitory” phenomenon that will soon fade away:

Regardless of near-term performance, inflation and wage growth fears likely will dissipate as we move through 2022. This should provide further market upside as this new bull market matures.

In October, White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki attempted to defend White House Chief of Staff Ron Klain’s tweets on inflation by arguing a variation of Surowieki’s thesis:

"So I think the point here is, what some of these critics are saying is we don’t know if what they’re saying is if what they thought was great was when the unemployment rate was double what it is today," Psaki said. "Or when people were locked in their homes and therefore gas prices were lower. We’re at this point because the unemployment rate has come down and been cut in half because people are buying more goods because people are traveling and because demand is up."

"What the point is here," Psaki added. "Is that we are at this point because we’ve made progress in the economy."

On CNN’s “The Lead” in response to similar questioning by Jake Tapper, Psaki repeated this same basic theme:

“The fact is the unemployment rate is about half what it was a year ago. So a year ago, people were in their homes. Ten percent of people were unemployed. Gas prices were low because nobody was driving. People weren’t buying goods because they didn’t have jobs. Now more people have jobs. More people are buying goods. That’s increasing the demand. That’s a good thing.”

In other words, inflation is a thing to be celebrated because it means the economy is growing and things are getting better.

But are they?

Let’s examine the interplay of inflation on the economy to see what actually is happening.

Notes On Analytical Technique

First, a brief explanation of data sources and analytical technique is in order.

The two data sets I use here are the St. Louis Federal Reserve’s quarterly measurements of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), Seasonally Adjusted and the Consumer Price Index (CPI) as measured by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, both freely available online. As the CPI figures are given monthly, I take the figures for March, June, September, and December of each year in order to align the data with the quarterly GDP numbers, those being the ending months of each calendar quarter. I am working with data in both sets going back to 1997, and ending with the second quarter of 2021.

Because CPI and GDP are disparate measurements, the CPI being a straightforward index and GDP being the dollar-denominated gauge of economic output, in order to unify the presentations I focus on the overall trends and relative shifts in those trends. This is done by setting a baseline of 100 as the start of the data set, and then dividing each subsequent value in each data set by the starting value; multiplying that result by 100 gives for each data set an output of values that can be compared side by side for correlations as to the general trend and the relative magnitudes of changes.

Regarding GDP figures, because GDP is stated by the Federal Reserve in nominal dollars, the relative purchasing power of which shifts over time because of inflation, to bring the GDP figures into a constant-dollar framework I use a “GDP deflator” calculated by dividing the base CPI value by the corresponding subsequent CPI value, and then multiplying that by each GDP figure to achieve a “Real GDP” number. I am very deliberately not using the “Real GDP” figures produced by the Federal Reserve as I am unpersuaded that their calculations completely remove inflationary influences from GDP numbers over time.

This methodology is consistent with GDP Deflator calculations done elsewhere, and there are references online for those wishing further understanding on the process.

The calculated data used in the development of each graph is available here, in Microsoft Excel Format (.xlsx).

Inflation And GDP Growth—The Historical Trend

We begin by establishing what we mean when we say “inflation”—to follow any analysis of the topic it is imperative we proceed from a common set of terms.

The Federal Reserve defines inflation thus:

Inflation is the increase in the prices of goods and services over time. Inflation cannot be measured by an increase in the cost of one product or service, or even several products or services. Rather, inflation is a general increase in the overall price level of the goods and services in the economy.

Simply put, inflation is rising prices, regardless of cause.

We should also include a basic definition of “GDP”, to establish what we are interrogating when we scrutinize the numbers. Per the Bureau of Economic Analysis, GDP is defined thus:

The value of the goods and services produced in the United States is the gross domestic product. The percentage that GDP grew (or shrank) from one period to another is an important way for Americans to gauge how their economy is doing. The United States' GDP is also watched around the world as an economic barometer.

Put another way, GDP is the aggregate dollar value of everything produced in the US.

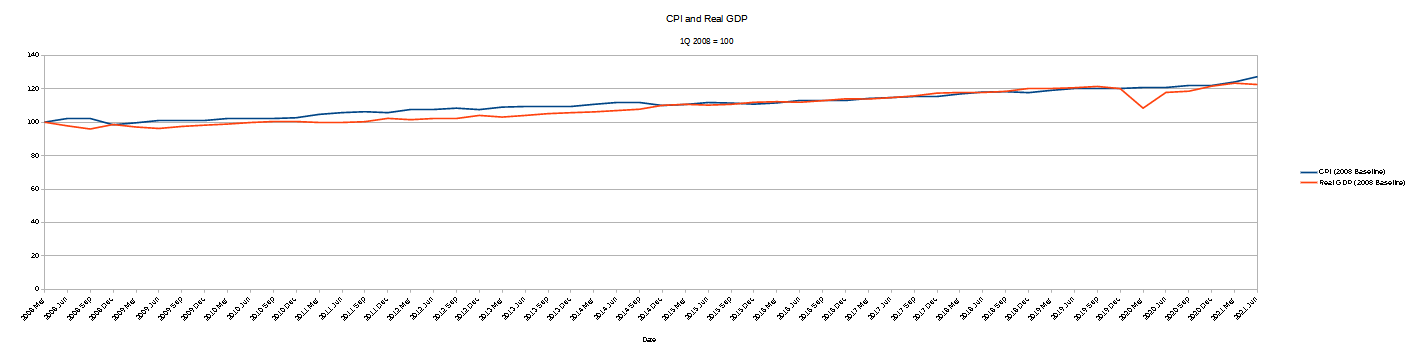

We start the analysis by looking at the long term trend for both CPI and GDP since January of 1997. Straight away we can see some important aspects arising from the comparison.

The most notable characteristic of CPI and GDP is that, by and large, they fall more or less on along a similar trend line. GDP growth has, over the past few decades, largely been mirrored by a rise in prices. It is this long-term correlation that most likely is what leads commentators such as Jen Psaki to argue that inflation is the consequence of economic growth.

However, that logic does not hold upon close scrutiny. In order for that interpretation to be accurate, the trends would have to match in both directions—GDP declines would have to be matched in both timing and magnitude by CPI declines, and this long-term trend chart shows clearly that is not the case. The two lines diverge somewhat beginning in 2008—which is of course the beginning of the Great Financial Crisis and subsequent recession.

There is an even more dramatic divergence in 2020, which is of course the consequence of COVID-induced lockdown measures nationwide. Note that prices did not drop appreciably at that time, but continued along the same upward trend. If economic growth led to inflation, an economic decline should lead to deflation, which would be declining price levels.

Reviewing the GDP and CPI data, therefore, we cannot conclude that inflation is a byproduct of GDP growth.

What is the correlation between GDP and CPI? The chart clearly illustrates correlation of some degree.

Price Rises Are Not Output Increases

Review for a moment Surowieki’s comments from above: inflation—rising prices—and shortages are the results of people trying to buy more goods, and suppliers not having caught up to demand. In other words, inflation does not happen when people by more goods, but when they buy fewer goods. They may desire more goods, but are unable to actually purchase them for whatever reason.

Consequently, it is irrational to equate any rise in price with a rise in output—which would be the “common-sense” understanding of economic growth. Rather, price rises occur when output is either steady or declining. Given that inflation is fundamentally an increase in prices, we should therefore associate inflation with a decline in economic output, not an increase.

We can interrogate this further by remembering that GDP, both real and nominal, as an aggregate number, is representative of both economic output and price level—of both the number of widgets produced and the prices charged for each widget. Productive economic growth would be an increase in the number of widgets, and inflation is an increase in the price of a widget. This also matches what every economic commentator observes about inflation, that it occurs when people want to buy more goods and services but are unable to do so.

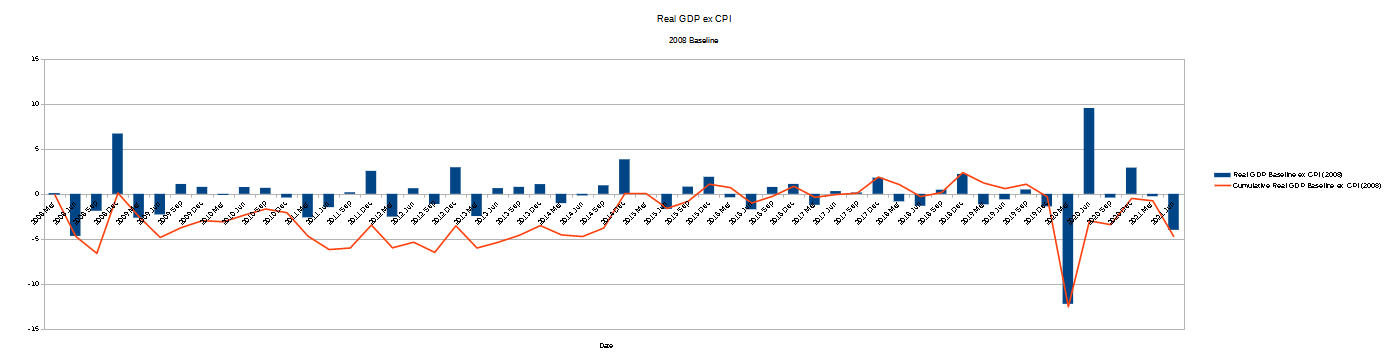

Consequently, we can derive a broad metric of productive economic output by removing the inflationary component from each GDP measurement. Baselining makes this fairly straightforward, as we merely need subtract the shift in the CPI baseline from the shift in the Real GDP baseline to achieve a baseline value of productive output, what I term “Real GDP ex CPI”. When we view the shifts in Real GDP ex CPI over time, both individually and as an accumulation, a far different portrayal of the overall economy emerges.

If we regard the accumulation of productive GDP as a broad metric of “wealth”, it immediately becomes apparent that the 2008 financial crisis obliterated all the accreted wealth in the US going back two decades prior, and that the subsequent “recovery” has never come anywhere near to replacing it.

Further, the lockdown policies of 2020 were multiple times more detrimental to the economy than the 2008 financial crisis, and that damage still has not been undone.

Different Time Frames Tell The Same Story

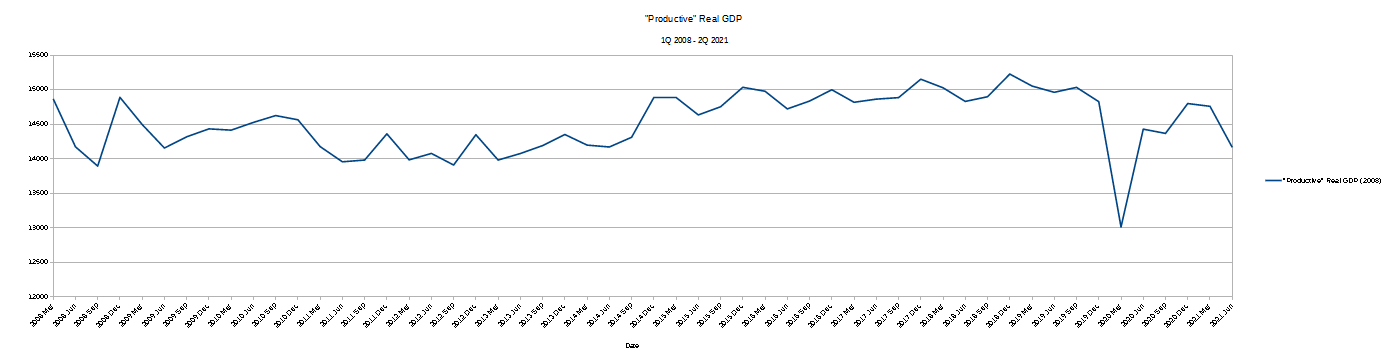

One advantage of this baselining methodology is that we can quickly zoom in on any time frame desired. If we bring the base period forward to 2008, we see the same trends and the same magnitude variances in GDP and CPI.

We also see more starkly how the 2008 financial crisis and the 2020 lockdowns devastated actual economic output.

We also see something that will enrage liberals and progressives: The period of the Donald Trump Presidency was overall a better period of actual economic growth than the Obama years, which we can see even more clearly by bringing the base period forward to 2017.

Before the 2020 lockdowns due to the COVID-19 pandemic (a full discussion of which would be several articles unto itself), from 2017 through 2019 actual economic output broadly rose in the US—not as much as the GDP numbers would suggest, but it still rose. This tracks with the comparison of CPI and GDP, which show that same period the GDP line above the CPI line.

The lockdowns resulted in a dramatic drop in productive economic output from which a full recovery has not occurred. As of the end of the analysis, the second quarter of this year (2021), the decline in productive economic output suggests full recovery from the 2020 lockdowns will be some time to come still.

In summary, when anyone speaks of “economic recovery”, understand they are not speaking of a recovery in productive economic output, whether they realize it or not.

Inflation Is Economic Distortion, Not Growth

Contrary to what Surowiecki, Schulze, Psaki, and others say and presumably believe, inflation is never a good thing. All levels of inflation are inherently a burden on an economy. Inflation distorts the economic picture by presenting a rosier picture of economic growth than is really the case.

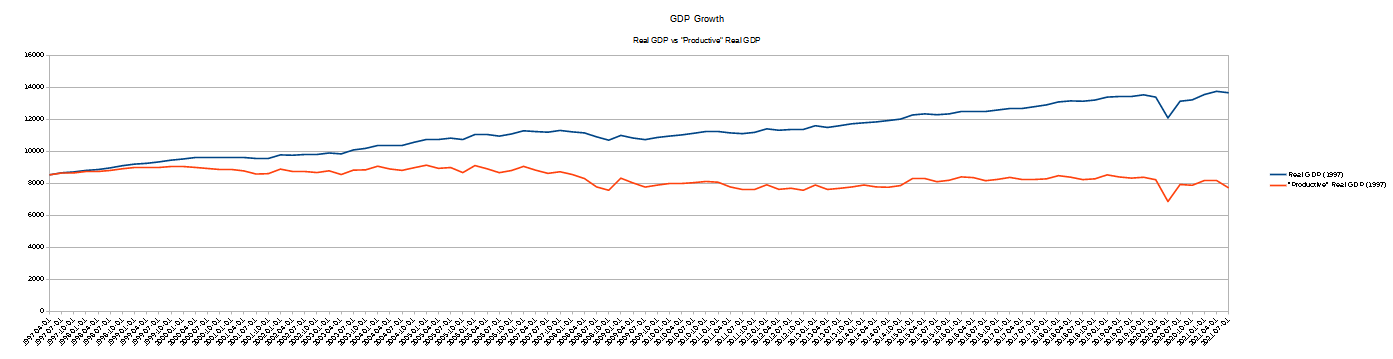

If we reverse the baseline calculation above, but use the Real GDP ex CPI values, we can see clearly how distorting inflation is on GDP measurement, and how it gets worse over time.

Using the 1997 base, the distortion looks like this:

Note that most of the distortion occurs prior to 2020—before inflation was presumably a problem.

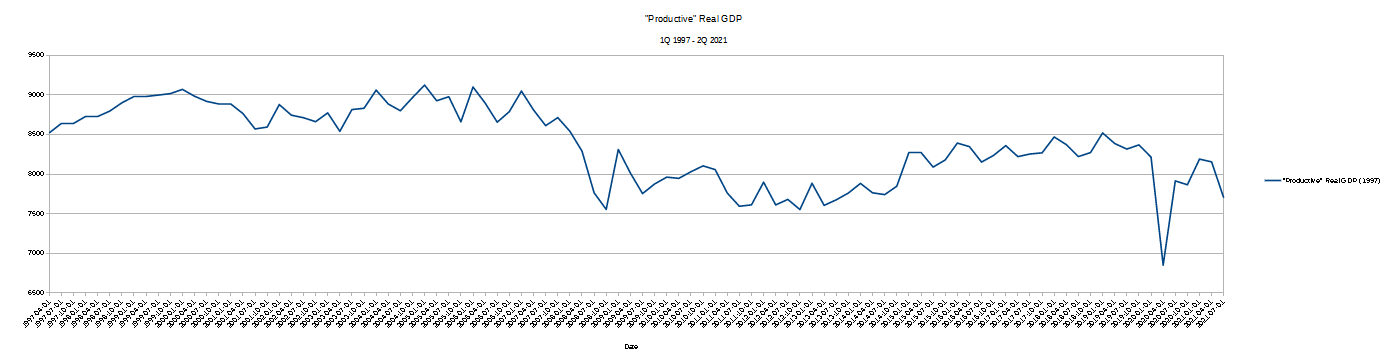

Viewed in this way, regardless of which base period we select, we see economic output (“Productive” Real GDP”) either unchanging or declining.

Calculating from 1997:

Calculating from 2008:

Calculating from 2017:

Contrary to the mainstream narratives, there has not been meaningful growth in overall economic output since before the 2008 financial crisis. Inflation—price increases—has been the bulk of the “growth” and has even masked decline in economic output. Indeed, so far in 2021 inflation has masked that decline, leading to talk of “recovery” when “decline” is a far better term, and “collapse” might be the term of the future.

Output Matters

Contrary to Jen Psaki’s assertions, people are not buying more stuff. People are simply paying more for stuff, but buying less of it.

That is the true impact of inflation: fewer goods, fewer services, higher prices. For most consumers, that is a crisis.