Britain's Winter Of Discontent Masks A Larger Food Insecurity Threat

Food Price Inflation Is A Problem. Possible Food Insecurity Is A Crisis

For several weeks now, the United Kingdom has been wracked with a number of rolling strikes across multiple industries, as workers take to the picket lines seeking pay increases commensurate with Britain’s accelerating consumer price inflation rate.

By some appearances, Britain is experiencing a general strike over prevailing wage rates and inflation.

Rail unions have already said they will wreak havoc on the train network over Christmas, while postal staff will join picket lines instead of delivering last-minute presents and cards.

And NHS nurses and paramedics are also due to walk out for several days, with fears that soldiers will have to be drafted in to cover gaps in care.

Add airports to the growing list of sectors experiencing strikes in the UK.

The Public and Commercial Services Union said its members at Gatwick, Heathrow, Manchester, Birmingham and Cardiff airports would strike for eight days between Dec. 23 and Dec. 31, one of the busiest times of year for international travel.

The common unifying thread in all these strikes: pay, and declining real wages in the face of inflation.

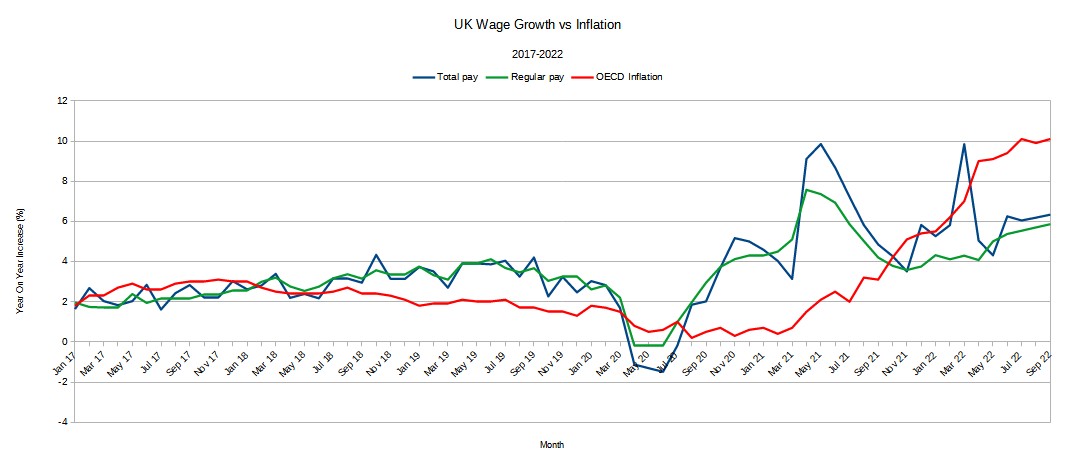

Much like in the US, while wages have been rising marginally during 2022, in real terms British wages have been in steep decline since the beginning of the year.

In “official” real terms, average wages in the UK have been declining by over 2% each month since April, after real wage growth in the UK turned negative the prior month.

In actual real terms, the negative wage growth is far worse, as the differential between the percentage year-on-year increase in total pay and the inflation rate per the OECD has exceeded 3% since April, and in some months has exceeded 4%,

Inflation in the UK, just as in the US, is threatening to undo all the real wage growth workers have enjoyed in recent years, especially just before and just after the 2020 pandemic lockdowns.

British labor is striking because they want this downward trend in their purchasing power stopped, one way or another.

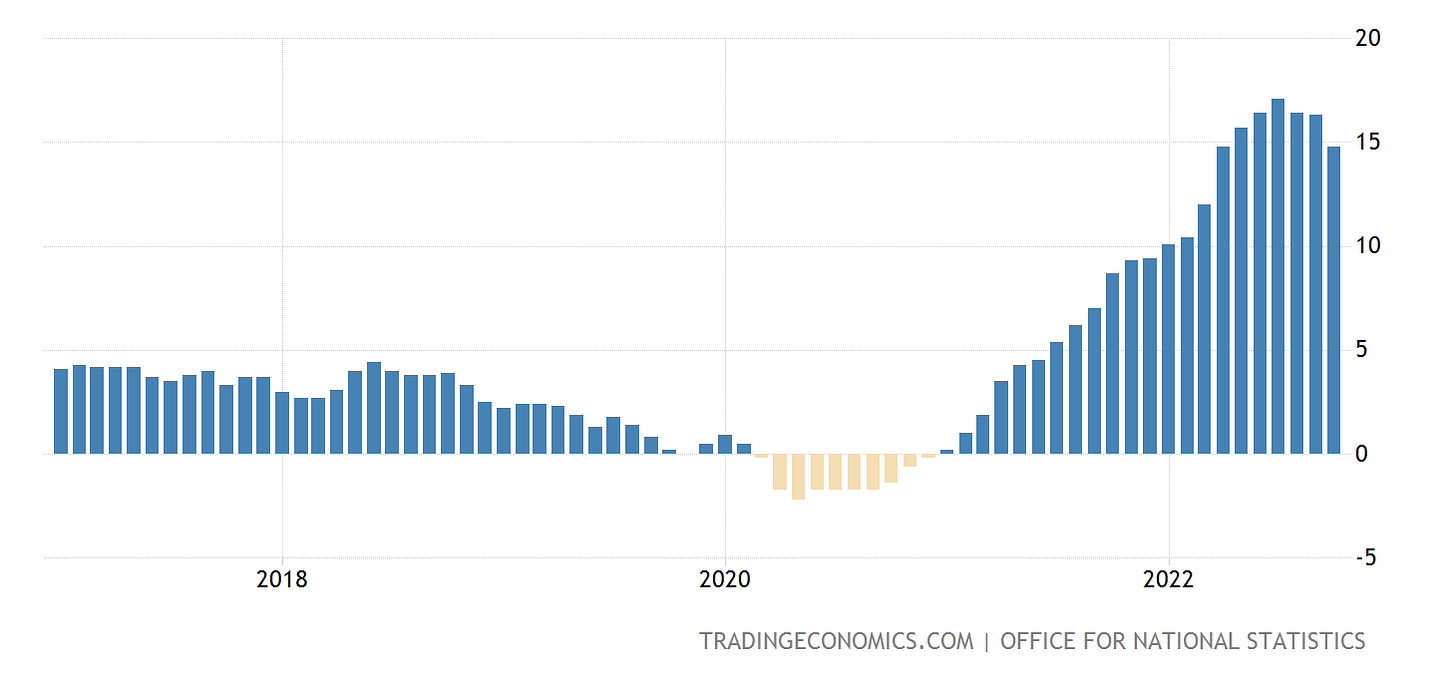

Inflation has been a growing economic problem in the UK since early 2021 (thus proving that the media narrative where all economic ills are blamed on Putin and his war in Ukraine substantially false; the war in Ukraine has been an inflationary factor in 2022, but fully half of the rise in inflation predates Putin’s invasion in February).

As in the US, much of the overall rise in consumer price inflation is attributable to rises in food and energy prices, as the much lower (but still rising) core consumer price inflation rate illustrates.

Food price inflation in particular has been rising steadily since mid-2021, rising faster and higher than overall consumer price inflation.

British workers are feeling the pinch of inflation not just when they fill up their gas tanks but especially when they shop for food, and while core consumer price inflation is showing signs of stabilizing in recent months, food price inflation in the UK is getting steadily worse, with no signs of stabilization within the upward trend thus far.

Already, energy price inflation and food price inflation are combining to alter cooking and eating habits in the UK.

Recent surveys indicate that as many as a third of single parents in the UK, and 14% of UK residents overall are skipping meals due to the runaway cost of living.

Three in 10 single parent households surveyed said they had missed meals as a consequence of runaway food prices. That compared with one in seven parents in couples and an overall figure of 14% in the poll by the consumer group Which?

In a very real sense, the deterioration of the British economy is showing up at dinner tables across the country—and it is not at all a welcome guest.

However, as distressing as food price inflation is, the impacts of producer price inflation on British farmers are potentially more severe, with producer price inflation having outpaced food price inflation up until this past summer.

Agricultural and food production costs have risen faster than farmer have been able to pass those cost increases on to consumers in the form of higher consumer prices.

This disparity is setting the stage for a potentially severe food insecurity crisis, as the rising costs diminish the available supply of several foodstuffs.

Rising costs could result in supply problems for energy-intensive crops including tomatoes, cucumbers and pears – which are on track for their lowest yields since records began in 1985 – and rationing at supermarkets as recently experienced with eggs, the union said.

The union said milk prices were also likely fall below the cost of production and that beef farmers were weighing whether to cut down on the number of cows being bred for slaughter in light of surging costs.

Supply challenges—including an ongoing avian flu pandemic that has been thinning poultry flocks globally—have already led some UK grocers to limit purchases of eggs to two and three boxes per customer.

Shoppers are being restricted to two boxes of eggs in Asda, and three in Lidl, to ensure availability.

Other supermarkets have not brought in limits but Waitrose said it is "continuing to monitor customer demand".

There's also evidence chains are experiencing limited stocks in some stores, although different factors may be affecting supplies.

Fertilizer prices, while they have stabilized in recent months, remain significantly higher than 2021 levels, raising the specter of reduced harvests in 2023 and beyond, raising the possibility of not just food price inflation but outright food insecurity even in developed nations.

Britian’s National Farmer’s Union is raising an alarm that inflation and soaring energy costs are an immediate threat to food production in the UK this year, with fruits and vegetables—foodstuffs which are particularly energy intensive to produce—on track for poor crop yields this year, not just next.

"Shoppers up and down the country have for decades had a guaranteed supply of high-quality affordable food produced to some of the highest animal welfare, environmental and food safety standards in the world," NFU president Minette Batters told the BBC.

"But British food is under threat... at a time when global volatility is threatening the stability of the world's food production, food security and energy security.

"I fear the country is sleepwalking into further food supply crises, with the future of British fruit and vegetable supplies in trouble."

The official position of the British government is that the UK gets its food from a diverse range of sources, including imports, thus reducing the possibility of major food shortages and food insecurity.

However, the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) said Britain has a high degree of food security which is "built on supply from diverse sources", including strong domestic production as well as imports through stable trade routes.

Still, despite the government’s official view that the UK enjoys high food security, some grocery stores are rationing eggs. That is a reported reality today, not tomorrow or the day after.

Nor is this the first time that various commentators have called attention to potential vulnerabilities in Britain’s food supply chains. In 2019, as the country was working through the tortuous Brexit negotiations, bank analyst David McCarthy noted that as much as 80% of Britain’s food supply is imported.

In a research note to clients dated January 3, HSBC analyst David McCarthy and his team wrote, "It is widely believed that 50% of food is imported into the UK," he wrote. Among Conservative party members, 76% believe warnings about a no-deal Brexit are "exaggerated or invented, and in reality leaving without a deal would not cause serious disruption," according to a recent YouGov poll.

The 50% statistic underrepresents the reality, McCarthy says. In reality, "80% of food is imported into the UK," he wrote. The lower number "defines food processed in the UK as UK food, even though the ingredients may have been imported. For example, tea is processed in the UK, but we grow no tea — it is all imported. When ingredients are counted as imported, the real figure is over 80%."

The recurring theme from the Brexit negotiations then and the inflation crisis now is that Britain’s food supply remains particularly vulnerable to a range of supply shocks, many of which are becoming increasingly likely as inflation and economic deterioration across Europe imperil a variety of UK supply chains.

Moreover, we should never lose sight of the reality that food broadly speaking is a good without any possible substitutes. Everyone needs to eat, and no one has the option of simply not eating when costs get too high or supply gets too low.

Yet food has become more than merely a necessity of living. It is a complete industry unto itself, with its own lengthy global supply chain. Global inflation and a destabilizing global economy present palpable threats to that supply chain, with disruptions and dislocations all too easily predictable. Fertilizer and energy are a vital part of that supply chain, and the availability of both is becoming increasingly problematic in the world.

Food price inflation is a serious problem, for the UK and for the entire world. However, should food supply chains become disrupted, food insecurity in the form of food scarcity will be the crisis of the moment. That inflection point, where food is simply not available at any price, is not nearly as far off for the UK as many would like to believe.

Is this not in sync with global elites’ agenda to hasten depopulation and catalyze civil unrest?