We've Had Food Price Inflation. Now We Get Food Insecurity

Without Fertilizer, There Is Not Enough Food To Feed Everyone

The good news for the world is that global food price inflation is very much on the retreat. Real food price inflation as measured by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization’s Food Price Index has declined for the past six months, with prices for some food categories moving from disinflation to outright deflation.

The FAO Food Price Index* (FFPI) averaged 136.3 points in September 2022, down 1.5 points (1.1 percent) from August, marking the sixth monthly decline in a row. The FFPI's decline in September was driven by a sharp fall in the international prices of vegetable oils and moderate decreases in those of sugar, meat and dairy products, more than offsetting a rebound in the cereal price sub-index. Despite the new decline, the FFPI remained 7.2 points (5.5 percent) above its value in the corresponding month last year.

That’s the good news. The bad news is that the declines are unlikely to last, and the downward trends in global food price inflation are highly likely to reverse and climb even higher than the extremes seen both in early 2022 and early 2021. Barring an agricultural miracle, the stage is set for significant shortages of basic food stuffs worldwide, leading first to extreme food price inflation and then to food insecurity in many parts of the world. Hunger and even famine are not outside the realm of possible outcomes.

Fertilizer Production Is Becoming More Expensive

The key indicator of the future of food prices is the price of fertilizers used to grow crops—and fertilizer is more expensive than before.

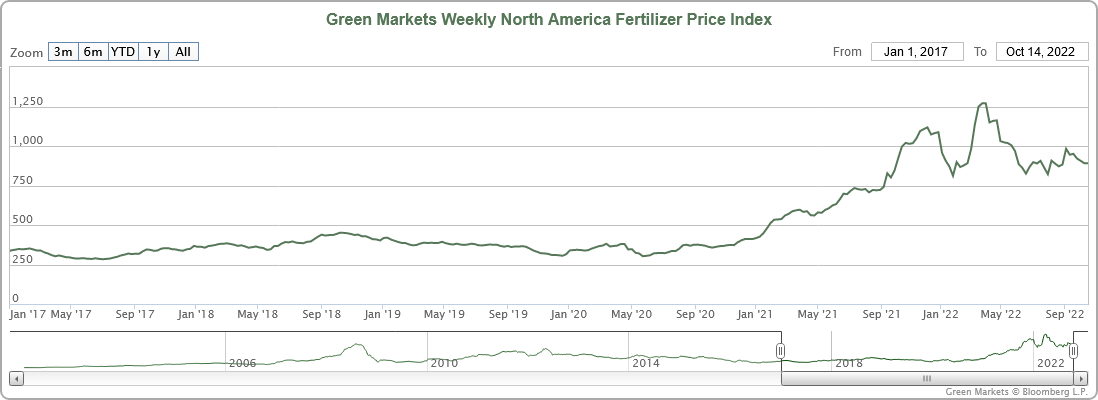

While producer price inflation for fertilizer and fertilizer ingredients peaked in early 2022 and has been in a downward trend since, the reality for the North American markets is that fertilizer prices have more than doubled since January 2021, and the disinflation trend has merely stabilized fertilizer prices at more than 200% of the January 2021 levels.

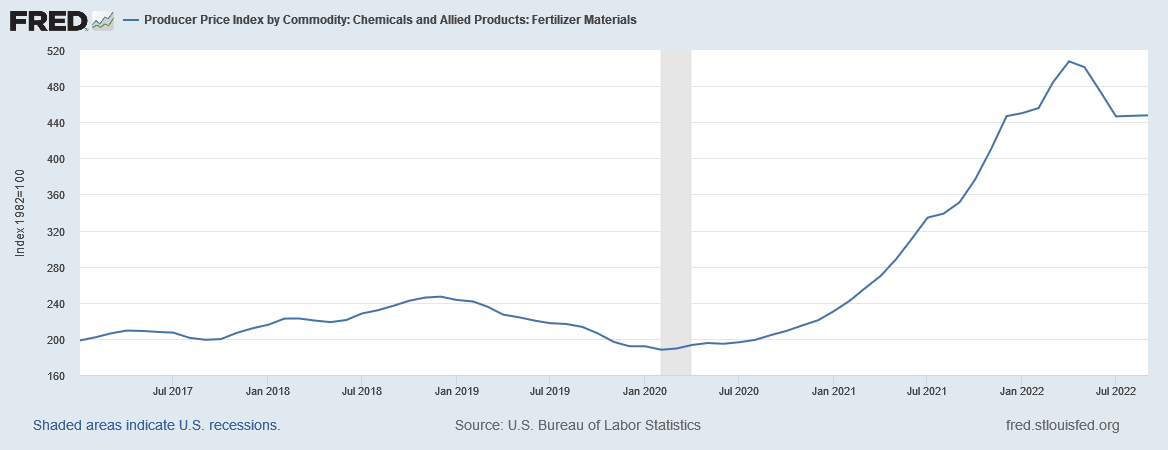

Nor is the price of fertilizer likely to come down, as the producer price index for fertilizer materials has also risen to similar extremes.

The disinflation trend of the past few months, while significant, has still left year on year producer price inflation for fertilizer materials at over 27%.

Nor is it merely the materials exhibiting significant inflation year on year. Fertilizer production has seen extreme producer price increases across the board.

The disinflation trend in nitrogenous fertilizer manufacturing has left producer prices for that industry at 48.6% above year ago levels, and the only reason that represents a steep decline is because producer price inflation for nitrogenous fertilizer manufacturing peaked in April at nearly 120% year on year.

Even fertilizer import price inflation is considerably higher than 2021 levels, sitting at 56% for September after peaking at more than 136% year on year in February.

By every metric, fertilizer is more expensive than before, and all indications are that it is going to stay that way for the near future at least.

Market Prices Agree

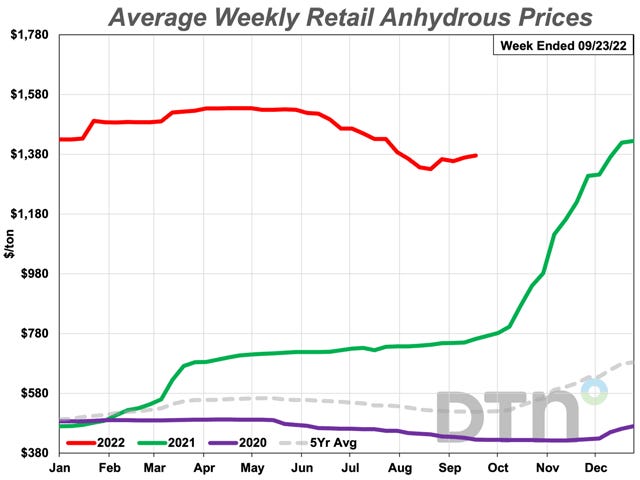

Market prices for fertilizer confirm trend in fertilizer prices. As tracked by data and analytics firm DTN, fertilizer prices have remained at the high levels established in 2021.

Five of the eight major fertilizers were just slightly lower. DAP had an average price of $950/ton, MAP $1,005/ton, potash $875/ton, 10-34-0 $860/ton, and UAN32 $670/ton.

Three fertilizers were slightly more expensive than they were a month ago. Urea had an average price of $811/ton, anhydrous $1,376/ton and UAN28 $578/ton.

Even when specific fertilizer prices move down, they are still well above the five year historical averages.

Between 2021 and 2022, fertilizer prices have nearly doubled.

For some crops, fertilizer prices per acre have more than doubled. In the spring of this year, prices for anhydrous ammonia fertilizers used for corn production hovered at around $250/acre. 2020 prices had been as low as $99 per acre.

Prior to this year, the previous highs were around $160 per acre, observed from 2011 to 2013. After peaking, fertilizer prices slowly adjusted lower to around $99 per acre by the spring 2020. Last year, prices lifted off post-pandemic lows.

Fertilizer prices per bushel for 2022 are estimated to be more than double 2020 levels, and well above previous peaks set in 2011-2013.

As a component of agricultural production—of food production—fertilizers are becoming an increasingly costly ingredient.

Fertilizer Price Inflation In 2022 Likely To Impact Food Production In 2023

Agricultural data firm Farmers Business Network, in their 2022 Fertilizer Transparency Report, is anticipating a surge in fertilizer prices as farmers prepare their fields for 2023 plantings.

As U.S. farmers finish up fall harvest, their attention will turn to fertilizer applications. While fertilizer values have backed off the highs of early 2022, they still remain well above historical norms. Data also indicates that prices may surge even higher in response to strong farmer demand in the coming months.

Because fertilizer production is closely tied to the natural gas industry, and because a number of fertilizer precursors are exported from Russia—and thus enmeshed in the ongoing war in Ukraine—rising fertilizer prices are likely to impact planting decisions and fertilizer application levels (thus impacting crop yields) for 2023.

"With natural gas prices still high and major market disruptions due to the Russia-Ukraine war, we don't expect fertilizer prices to normalize in time for farmers' 2023 crop planning," said FBN Chief Economist Kevin McNew. "The widespread regional variation in fertilizer prices-about twice as much with nitrogen fertilizers as potash fertilizers-could be symptomatic of the same lack of transparency FBN has previously exposed in other input markets such as seed. A lack of price transparency can impact ROI significantly, tighten operational budgets, and make crop planning for next year even tougher for farmers in an already challenging environment."

Nor are the price rises and impacts isolated to North American markets. Fertilizer production is a global industry, and is tied to the global natural gas and petroleum industries. The challenges facing US farmers for 2023, particularly from natural gas price increases, are the same ones facing farmers worldwide.

In the U.S., natural gas prices are up 400% in the past two years. However, this figure pales in comparison to the 3,600% explosion in natural gas prices in Europe.

Because Europe’s manufacturing sector has largely relied on imported natural gas from Russia, that lost supply source has sent natural gas prices soaring to epic heights. Considering that natural gas generally accounts for 70% or more of the costs to produce nitrogen fertilizers, this has had seismic impacts on the nitrogen fertilizer market. Europe is a sizable producer and user of nitrogen fertilizers; the dramatic rise in natural gas has taken many manufacturers offline or deeply diminished their capacities. While the U.S. has sizable natural gas and nitrogen capacity, both are being diverted toward world markets to satisfy huge shortfalls, causing U.S. nitrogen prices to remain elevated.

Fertilizer prices are already seen to be constraining anticipated fertilizer application rates for 2023.

When asked about intentions to change their fall 2022 fertilizer application rates, 74% of farmers said they would stay the same as in fall 2021. For those who plan to adjust, 17% said they would lower their application rates this fall while only 9% would increase application rates versus last fall. This suggests that fertilizer cost increases may be constraining some farmer application rates.

While rising food prices are incentivizing farmers to plant more acreage—plantings for corn, soybeans, and wheat are all forecast to increase in 2023—a reduction in fertilizer application rates suggests that crop yields per acre may be impacted, and the planned increases in planted acreage may not result in similar increases in overall crop yields.

Fertilizer Price Inflation Begets Food Price Inflation Begets Food Insecurity

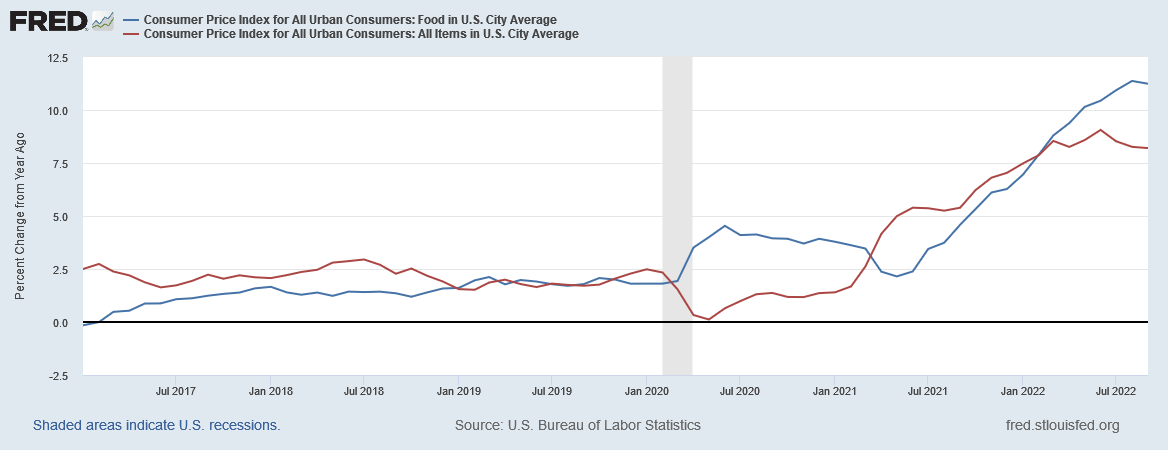

It is important to realize that, on the consumer end of the food production and supply chain, prices are still digesting a variety of supply shocks including an increase in fertilizer prices, with food price inflation as measured by the Consumer Price Index only just in September showing any decrease at all.

It is also important to realize that food price inflation in the US been rising faster than overall inflation as measured by the Consumer Price Index.

With fertilizer prices set to rise yet again, and food prices still absorbing the 2022 price hikes in fertilizer, food price inflation is almost certain to spike even more in 2023 and beyond.

More worrisome is the reality that food is one economic good for which there are no substitutes, nor is food a good that consumers can simply do without. Going without food is called hunger—and lots of people going without food is called famine.

While it would be an extreme and unsupportable interpretation of the data to suggest that famine is imminent in the United States, price and agricultural trends are not limited to the United States. The trends appearing in US agriculture are the trends that are or will appear in agriculture around the world.

That means that fertilizer prices are set to rise worldwide in 2023. That means that fertilizer application rates are likely to decrease worldwide in 2023. That means that crop yields may decrease worldwide in 2023—and that means that food production will suffer worldwide in 2023.

The rise in fertilizer prices and impacts on crops and crop yields is almost certain to produce a renewed surge in global food price inflation worldwide in 2023. For some countries—and even some communities here in the United States—a renewed surge in food price inflation will lead directly to an increase in food insecurity worldwide in 2023. For impoverished nations, the prospect of famine beginning in 2023 cannot be ruled out.

Hunger is coming….

How to stave off hunger: Relax the Renewable Fuel Standard, which diverts something on the order of 40% of the maize ("corn") grown in the USA to the production of ethanol to blend in with gasoline. The EU has similar legal requirements for fuel, although they tend to be more focused on feedstocks for biodiesel production, which generally aren't readily usable as inputs for food production. Still, they could re-purpose the land currently used to grow those crops to growing food crops, or even for the grazing of animals.

Bottom line: This is all manufactured as the elites wish to be rid of the masses.