China’s Bold Trade Move Could Backfire Big

No One Is Likely To Win This Latest Trade War Escalation

While President Trump was basking in the glow of seeming success for having brokered a long-sought ceasefire between Israel and Hamas, Xi Jinping on Thursday decided to rain heavily on Trump’s parade by announcing new sweeping export curbs on rare-earth minerals, products, and related technologies.

China has tightened export controls on rare earths and related technologies while barring its citizens from participating in unauthorized mining overseas, adding fresh strains to a sector central to its geopolitical leverage.

Foreign entities must now obtain a license from Beijing to export any products containing over 0.1% of domestically-sourced rare earths, or manufactured using China’s extraction, refining, magnet-making or recycling technology, the Ministry of Commerce said Thursday.

While this is not the first time China has ratcheted up trade tensions using its dominance in rare earths, in this latest escalation China applied its new export restrictions worldwide.

This is not merely an escalation of trade tensions between China and the United States. China is ratcheting up trade pressure with everybody.

As with all trade pressures and conflicts, China is flexing what Beijing believes is a potent economic muscle. China’s rare-earths restrictions are a play for global trading power and influence in the same vein as President Trump’s Liberation Day tariffs.

Whether this power play will end well for China, however, is far from certain.

Whether it will end well for the United States is equally far from certain.

Next Level Trade Protectionism

When we consider the scope of China’s restriction announcements, we are presented with a new level of trade protectionism from the Middle Kingdom.

China’s rare earths trade flex was executed in two parts.

Announcement 61 from China’s Ministry of Commerce focused on restricting the export of products made in China containing rare earth by any foreign entity.

(a) containing, integrating or mixing items originating in China in Part I of this Announcement manufactured overseas in Part I of this Announcement, and the items listed in Part I of Annex 1 of this Announcement account for 0.1% or more of the value of the items listed in Part II of Annex 1 manufactured abroad;

Announcement 62 placed similar restrictions on China’s rare earths’ refining technologies.

The following items shall not be exported without authorization:

(A) rare earth mining, smelting separation, metal smelting, magnetic material manufacturing, rare earth secondary resource recycling related technologies and their carriers; (control code: 1E902.a)

(B) rare earth mining, smelting separation, metal smelting, magnetic material manufacturing, rare earth secondary resource recycling related production line assembly, commissioning, maintenance, maintenance, upgrading and other technologies. Regulatory code: 1E902.b)

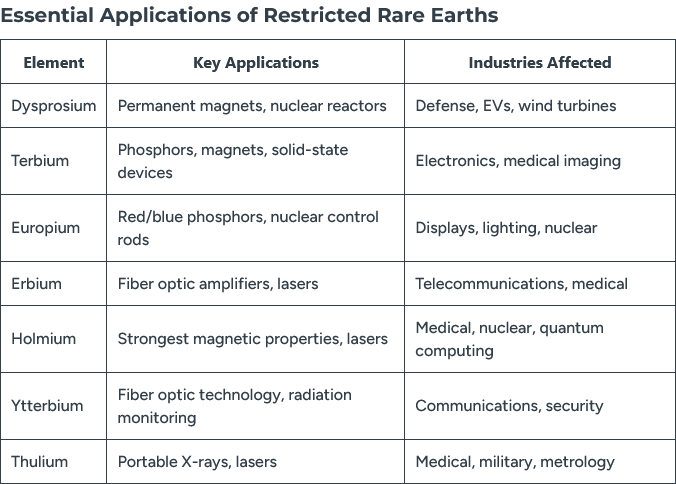

The products and technologies being restricted play key roles in a number of high-tech industries, including the defense sector.

Notably, China is not singling out the United States with these restrictions. The broad language in both announcements gives them global scope. Additionally, China is seeking to limit not just the export of rare earths and products containing significant amounts of rare earths, but also the use of Chinese refining technologies even overseas.

One aspect of this trade flex seems certain: China wants to protect its stranglehold on 90% of the world’s rare earths processing capacity.

The timing of the restrictions presumably is driven by anticipated trade talks with the United States—that is certainly the assessment of many China watchers—although there is no denying that a major bone of contention in trade negotiations between the US and China has been China’s monopoly position.

“From a geostrategic perspective, this helps with increasing leverage for Beijing ahead of the anticipated Trump-Xi summit in (South) Korea later this month,” said Tim Zhang, founder of Singapore-based Edge Research.

The rules give China more control over the global rare-earth supply chain - a major sticking point in recent lengthy trade negotiations with Washington.

China’s trade flex in rare earths, if sustained, is an emphatic exploitation of that monopoly position.

China Denies Restrictions Are An “Export Ban”

Unsurprisingly, Beijing defends the export restrictions as “legitimate”, rejecting US claims of economic coercion and justifying the restrictions as enhancing China’s national security.

“These controls do not constitute export bans. Applications that meet the requirements will be approved,” a commerce ministry spokesperson said. “China has fully assessed the potential impact of these measures on the supply chain and is confident that the impact will be very limited.”

Beijing’s new curbs also require foreign entities to obtain a license to export products containing more than 0.1% of domestically-sourced rare earths, or manufactured using China’s extraction, refining, magnet-making or recycling technology. Applications for items that could be used in weapons or other military purposes will be denied.

While the additional export restrictions may not constitute an outright ban on rare earths exports, they also leave no doubt that China is claiming the right to ban those exports whenever it decides to do so, for any reason.

Equally unsurprising is China’s almost reflexive placing of blame on the United States and President Trump’s muscular approach to trade negotiations.

China’s commerce ministry said in a lengthy statement its export controls on rare-earth elements - which Trump on Friday called “surprising” and “very hostile” - followed a series of U.S. measures since bilateral trade talks in Madrid last month.

Beijing cited the addition of Chinese companies to a U.S. trade blacklist and Washington’s imposition of port fees on China-linked ships as examples.

“These actions have severely harmed China’s interests and undermined the atmosphere for bilateral economic and trade talks. China firmly opposes them,” the ministry said.

China’s desire to make the United States out to be the bad actor may be part of Beijing’s rationale for making the export restrictions apply globally rather than just to the United States. The expanded scope of the restrictions over prior maneuvers puts non-US companies potentially in harm’s way. If Washington does not succeed in persuading Beijing to moderate its position, Europe and Canada stand to suffer alongside the United States.

Will Europe pressure Trump to be more conciliatory towards China over trade? Certainly European countries have good incentive from these restrictions to seek a deescalation of trade tensions broadly.

Even as China is escalating those tensions, Beijing also is indicating an ironic desire for reducing those tensions—quite possibly to avoid the United States taking similar actions with other materials essential to the Chinese economy.

Even as it flexes that power, Beijing is signaling interest in cooling tensions. China wants to work with the U.S. to create “export control dialogue mechanisms” to help ensure “security and stability of global industrial and supply chains,” a Chinese Commerce Ministry spokesperson said Thursday.

That may be more than just rhetoric. The Trump administration’s freeze earlier this year on exports to China of ethane — a chemical essential to China’s petrochemical industry — was a reminder to Beijing that the U.S. can also weaponize its exports to inflict pain on the Chinese economy.

The possibility cannot be dismissed that this is a gambit to improve China’s negotiating position with the United States over trade.

What should not be overlooked is the degree to which this is a gambit. While China has certain economic leverage with regards to other countries, its economy is far from the picture of robust health, and the Middle Kingdom’s capacity to withstand a protracted trade dispute is far from certain.

Can China Sustain An Export Ban?

China’s great challenge with trade restrictions is that it is more dependent on exports than the United States for economic growth.

That challenge is exacerbated by the reality that China has not enjoyed an abundance of economic growth recently, which made the outcome of this past spring’s trade tiffs between the US and China quite problematic.

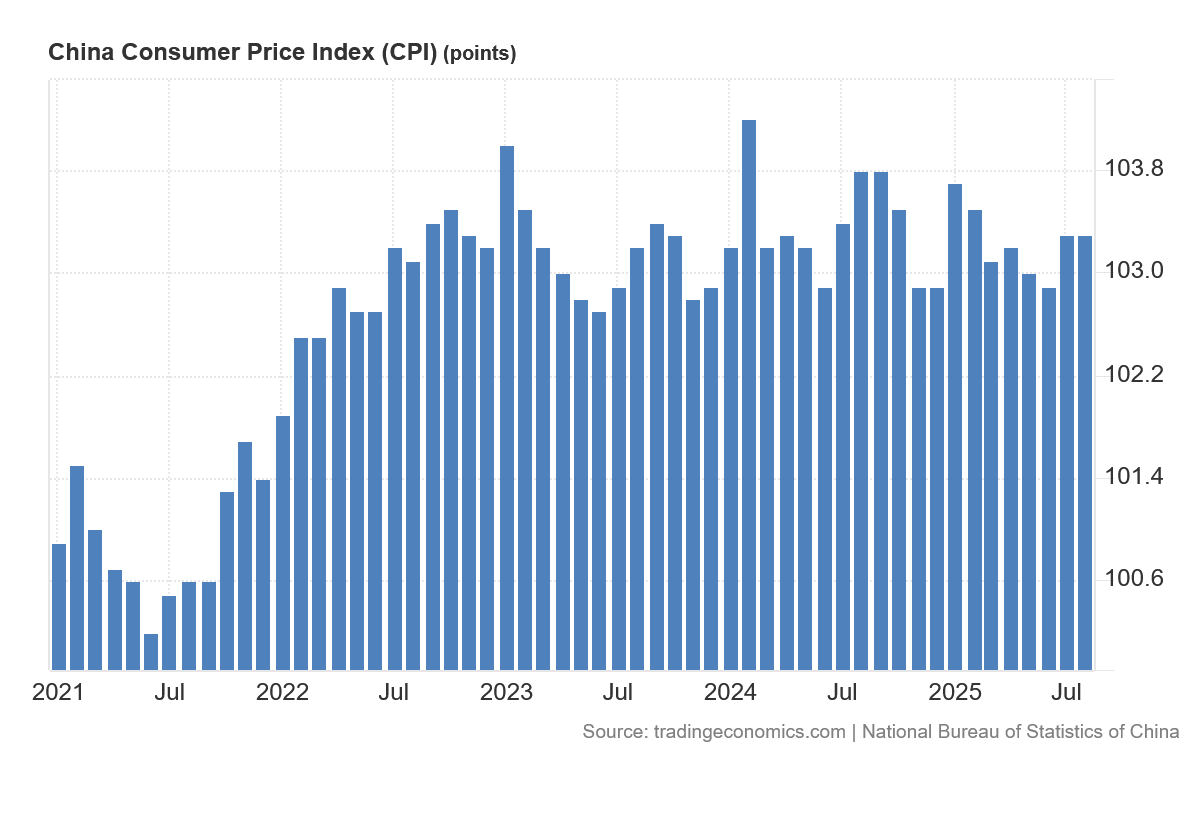

China has been mired in deflation for quite some time. Domestic demand is not something China has had in abundance, and we can see that by looking at their Consumer Price Index data.

China’s Consumer Price Index has not rising appreciably since the spring, indicating that, to date, China has still not succeeded in significantly stimulating domestic demand.

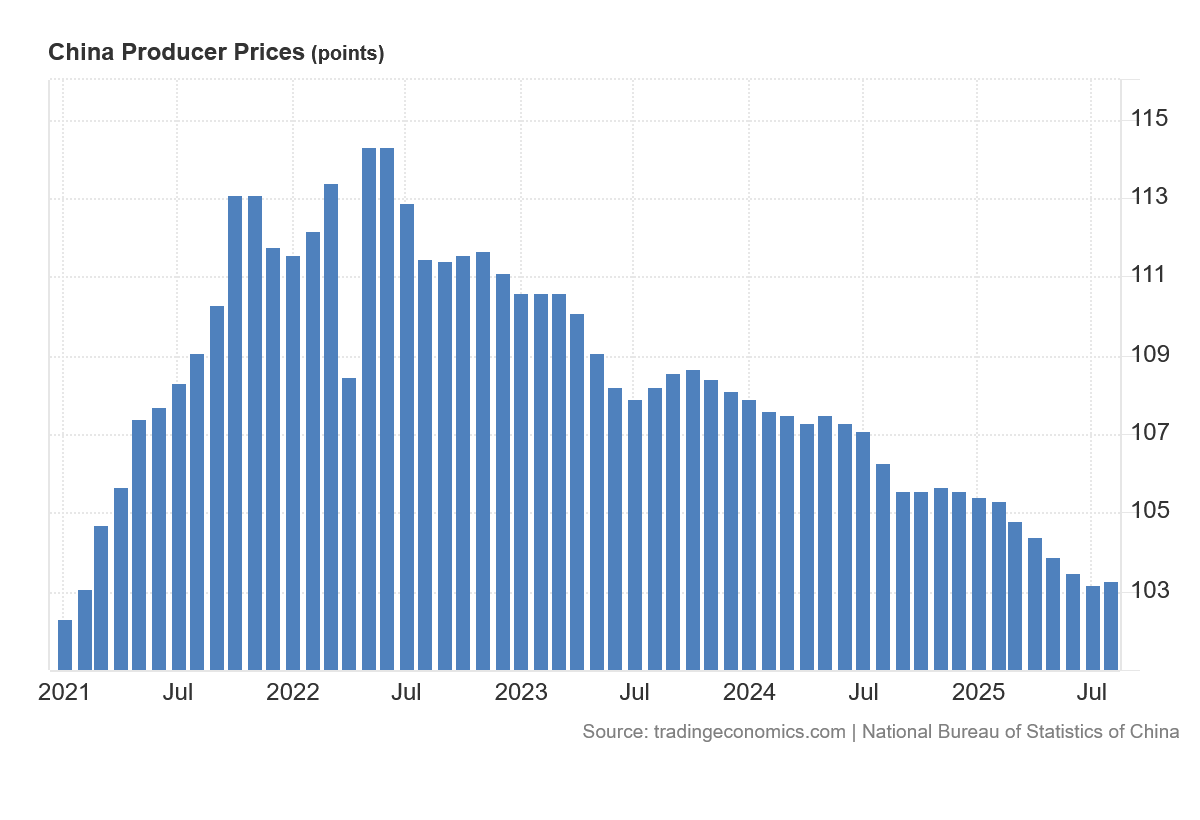

Even more ominous for China’s export prospects, however, is the persistent long-term decline in producer prices.

Just as a lack of consumer price inflation indicates a lack of consumer demand in China, a lack of producer price inflation indicates an overall lack of demand for Chinese goods—including in export markets.

Restricting exports at a time when there is stagnant or declining demand for exports is unlikely to be effective at stimulating any nation’s economy.

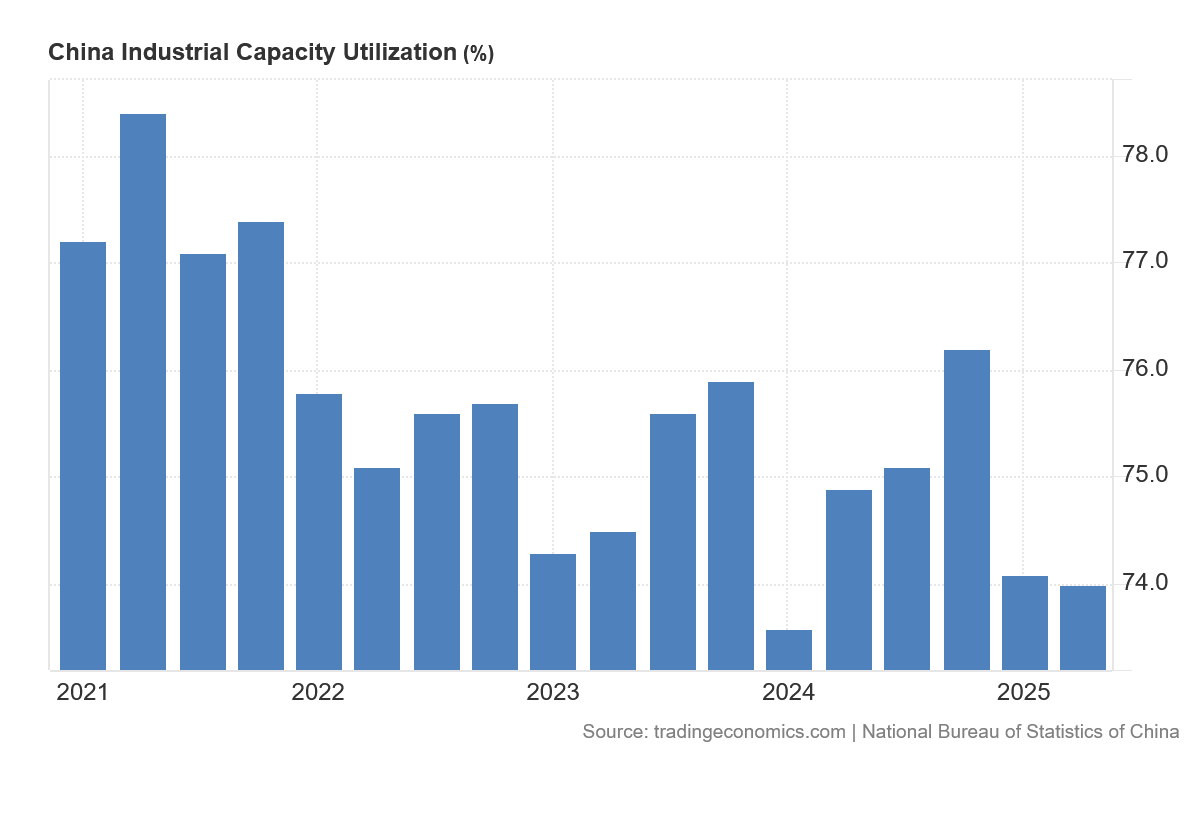

The lack of producer price inflation is reflected in China’s declining industrial capacity utilization.

China, long heralded as the world’s primary manufacturer, is steadily doing less and less manufacturing.

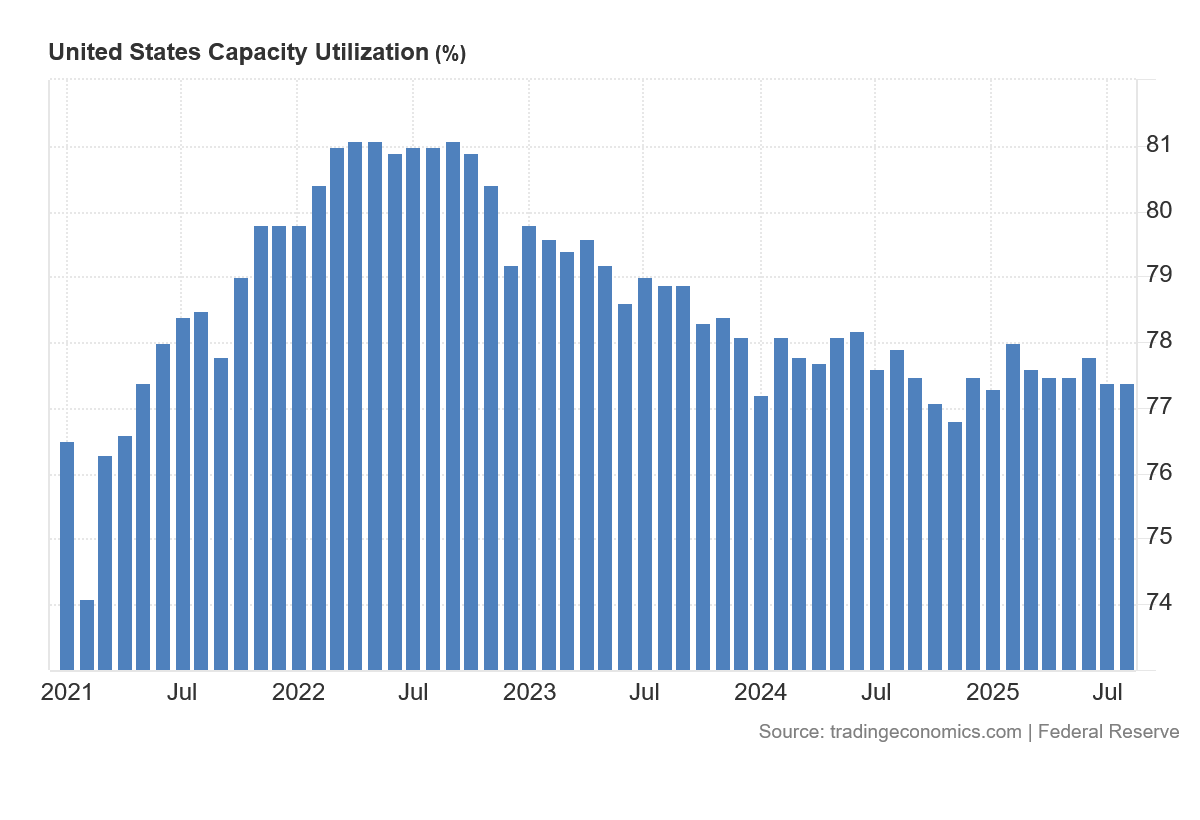

Ironically, at present, even with America’s own manufacturing woes, the US enjoys greater industrial capacity utilization than China, at 77% compared to China’s 74%.

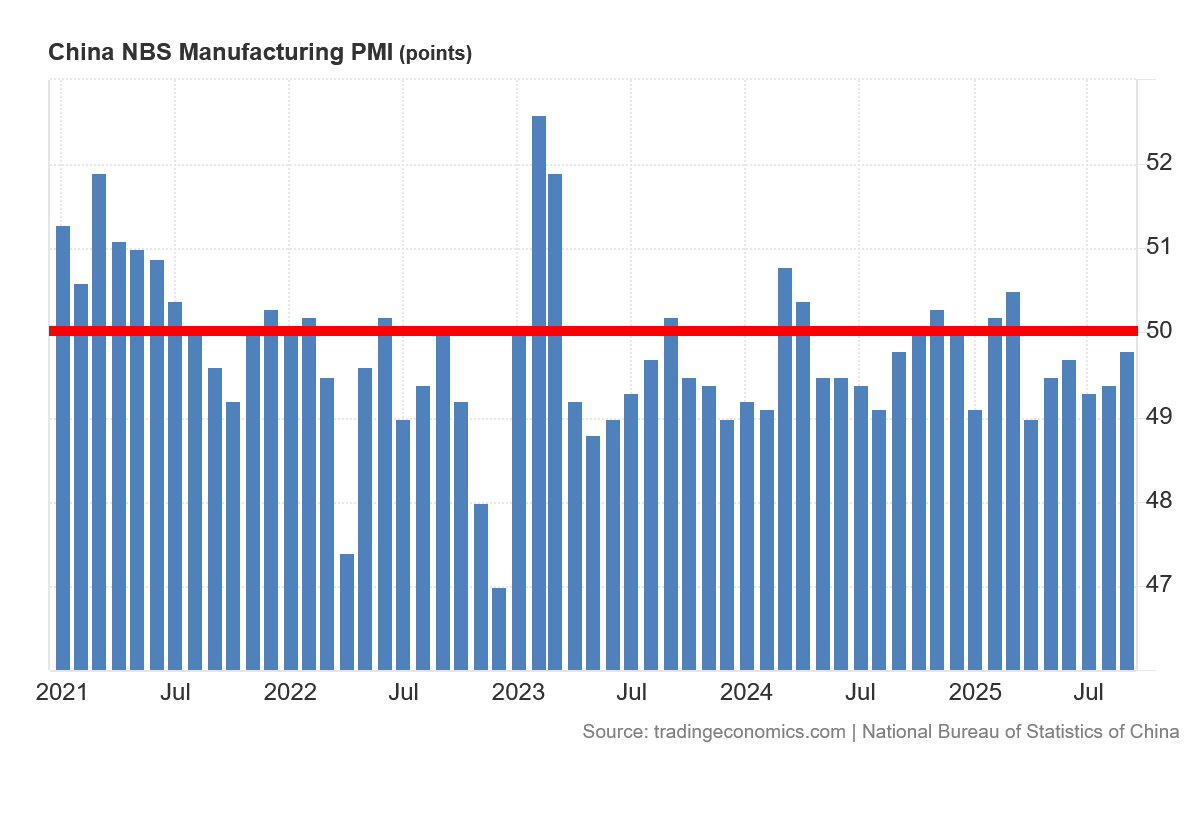

China’s manufacturing weaknesses are underscored by their own self-reported and ongoing contraction of their manufacturing sectors.

A shrinking manufacturing base is not a foundation upon which sustained export growth can occur, and by China’s own PMI data, manufacturing has been generally contracting since mid-2021.

Manufacturing decline carries another problem for China—unemployment. Both China’s general unemployment rate and youth unemployment rate have risen sharply in recent months.

It is hardly surprising that China’s stock markets responded to the export restriction announcements by shedding significant market value.

Will China’s need to export whatever it can to elevate its economy overall trump its desire to maintain control over global rare earths markets?

Only time will tell the answer to that question, but there is no denying that China’s rare earths gambit revolves around precisely that question.

Can The US Survive A Potential China Export Ban?

After China announced the trade restrictions on rare earths, President Trump responded with the bombast and counterpunch that has by now become a Trump trademark.

Given China’s aforementioned stagnation particularly in manufacturing, Trump’s response is a rational one: China is trying to hit the US where it will hurt the US, and so Trump is responding by trying to hit China where it will hurt China.

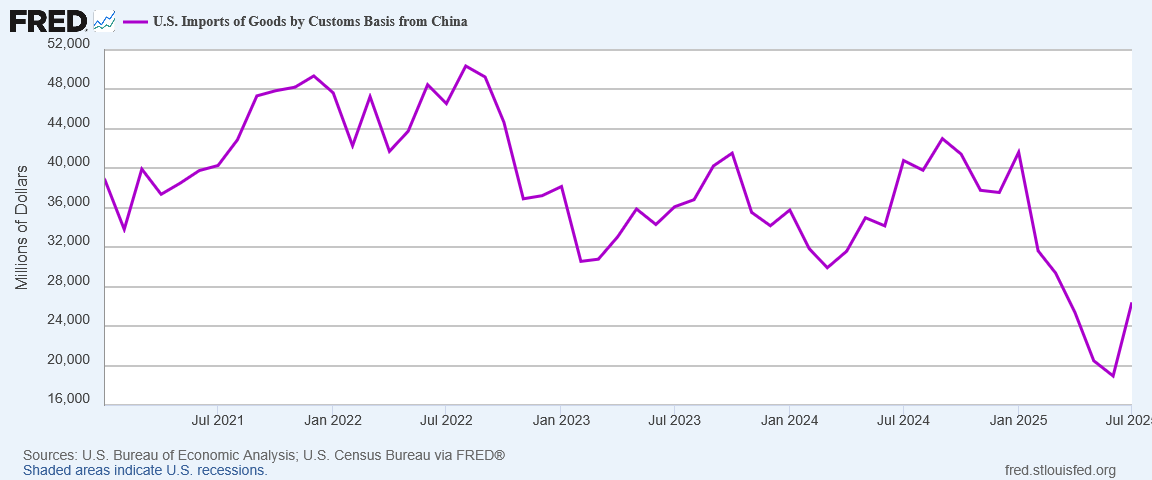

While the Liberation Day tariffs have thus far been a non-factor within consumer price inflation for the US, it is difficult to see how an additional 100% tariff on all Chinese imports would not be disruptive to the US economy, which still imports over $24 billion worth of goods from China as of July.

A 100% tariff is sure to push that level of imports down significantly, and that means that goods must either be sourced from other countries, sourced domestically, or substituted however imperfectly. All three scenarios involve a reordering of US supply chains.

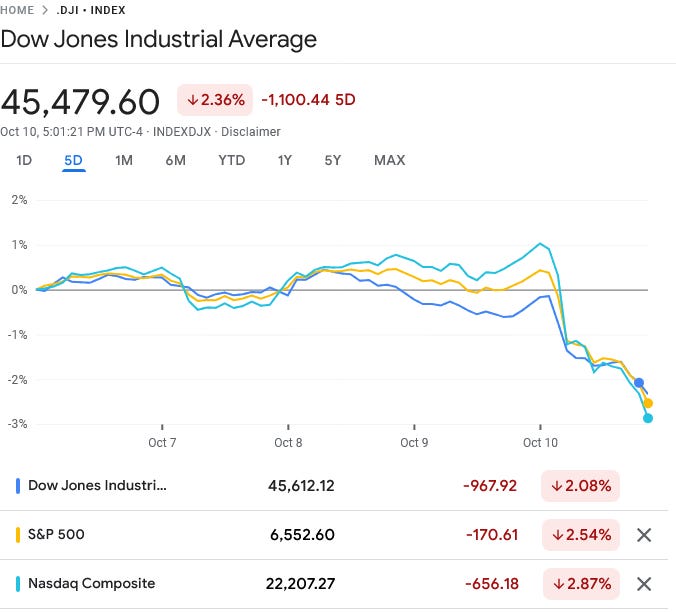

We should not be surprised that Wall Street responded to this latest tit-for-tat round between Donald Trump and Xi Jinping by taking a nosedive to close out the week.

Equally unsurprisingly, the tech sector was among the hardest hit—because that has the greatest exposure.

Shares of tech stocks with the most to lose from souring trade relations with China led the rapid sell-off Friday. Nvidia lost about 5%, while AMD dropped almost 8% and Tesla shed around 5%. Meanwhile, U.S. crude oil fell as investors grew increasingly concerned that higher tariffs might ultimately weigh on demand.

“It’s not surprising to see technology related stocks down the most today as they have significant exposure to China in both manufacturing and as a large customer,” Art Hogan, chief market strategist at B. Riley Wealth, told CNBC. “Clearly, our relationship with the second largest economy in the world just got more difficult,” he said.

In forex markets, the Dollar Index surrendered all of Thursday’s gains in response to Trump’s tariff announcement.

Right or wrong, Wall Street is not confident the US can prevail in this latest trade dispute with China.

A chief concern over the trade restrictions is their impact on the defense sector. Virtually all military technologies are heavily dependent on rare earths. China disrupting US supply chains for rare earths has some significant ramifications for US military readiness both now and in the future.

The newly announced restrictions represent China’s most consequential measures to date targeting the defense sector. Under the new rules, starting December 1, 2025, companies with any affiliation to foreign militaries—including those of the United States—will be largely denied export licenses. The Ministry of Commerce also made clear that any requests to use rare earths for military purposes will be automatically rejected. In effect, the policy seeks to prevent direct or indirect contributions of Chinese-origin rare earths or related technologies to foreign defense supply chains.

While the Trump Administration is already pursuing alternative supply chains for rare earths, building those supply chains out to fully replace US demand for Chinese-supplied rare earths will take time.

With neither the US nor China having an unassailable economic position, and both the US and China having significant capacity to inflict economic pain on each other, the outcome of this latest escalation is far from certain. The United States could easily find itself on the losing side.

Yet we have been here before, and quite recently. It was just this past spring, on the heels of the Liberation Day tariffs, when China announced export restrictions on rare earths targeting the United States. Eventually, both China and the US ratcheted down the trade war rhetoric and eased off both tariffs and trade restrictions.

Will that happen again? It could. On Sunday, President Trump was sounding more conciliatory towards China, posting on Truth Social that Xi Jinping just “had a bad moment.”

This morning, heading into the opening, Wall Street was feeling guardedly optimistic, with stock futures moving higher.

Whatever the impetus, Trump’s softening tone is seen by some on Wall Street as creating space for de-escalation, just as happened earlier this year.

“As we saw earlier this year neither side can tolerate such high tariffs for long and the comments from President Trump over the weekend again point towards a path for de-escalation,” MUFG strategist Lee Hardman said.

Whether China will respond favorably to President Trump’s de-escalation signals rather than leaning into his earlier bombast is as of this writing an open question.

Long-Term Outlook Does Not Favor China

Certainly, China has reasons of its own to look for an off-ramp away from trade warfare.

While the US and China ultimately agreed to tone down their trade rhetoric back in April, the G7 nations also began developing plans to “de-risk” their rare earths exposure. By June, the “G7 Critical Minerals Action Plan” was drawn up. Although the plan does not mention China, there can be little doubt that its objective is for the G7 countries to wean itself off Chinese rare earths.

We, the Leaders of the G7, recognize that critical minerals are the building blocks of digital and energy secure economies of the future. We remain committed to transparency, diversification, security, sustainable mining practices, trustworthiness and reliability as essential principles for resilient critical minerals supply chains, and acknowledge the importance of traceability, trade, and decent work in contributing to our economic prosperity and that of our partners.

China, by targeting countries besides the US, has only added impetus to the G7 building global supply chains which do not involve China. China might be able to flex on rare earths in the near-term, but only at the expense of its long-term dominance.

Moreover, China is already paying a high environmental cost for its pursuit of rare earths dominance. Lacking the stringent environmental regulation that is the norm in the G7 countries, China’s rare earths mining and processing operations have resulted in considerable environmental damage.

But for decades in northern China, toxic sludge from rare earth processing has been dumped into a four-square-mile artificial lake. In south-central China, rare earth mines have poisoned dozens of once-green valleys and left hillsides stripped to barren red clay.

Achieving dominance in rare earths came with a heavy cost for China, which largely tolerated severe environmental damage for many years. The industrialized world, by contrast, had tighter regulations and stopped accepting even limited environmental harm from the industry as far back as the 1990s, when rare earth mines and processing centers closed elsewhere.

Rare earths pollution has inflicted demonstrable harm on local Chinese populations, as well degrading Chinese farmland—a decided problem for a country for whom food insecurity has been an omnipresent threat for centuries.

Once China loses its dominance in rare earths and the attendant economic leverage, it will also lose much of the economic capacity to deal with the lingering environmental effects from its pursuit of that dominance. An unnecessary trade war along the way only magnifies the problem.

Even without an immediate loss of rare earths dominance, China’s slowly stagnating economy is both a long-term problem and an immediate concern. The ugly economic truth for China is that it has for years been the “sick man of Asia”, and current economic trends do not show any improvement from that.

What was true this time last year remains true today: China is mired in deflation, and there still is no clear way out.

A protracted trade war with the world over rare earths is only going to exacerbate China’s economic pain and suffering, making economic recovery that much more difficult.

There is no aspect of a trade war which works either to China’s short term or long term benefit.

For Both Sides, Only A Pyrrhic Victory

Even if China should succeed in compelling President Trump to retreat on tariffs, that victory is almost sure to be of a Pyrrhic variety. Not only will China’s economy have suffered in the short term, but the G7 plan to shift rare earths supply chains away from China has received new impetus and urgency, courtesy of Xi Jinping. Given that there are alternate sources of rare earths, the G7 effort to wean itself off Chinese rare earths production and processing will eventually succeed. Far from securing China’s economic dominance over rare earths, these latest trade restrictions will, over the longer term, work to end that dominance permanently.

At the same time, President Trump compelling Xi Jinping to retreat on rare earths is equally likely to be a Pyrrhic victory. As we have seen repeatedly in recent years, supply chains, once disrupted, do not recovery quickly. If the tariffs go into effect, and remain in effect for any length of time, the US economy is certain to suffer significant damage no matter the final outcome of this latest dispute.

As with so many geopolitical conflicts, both economic and otherwise, we should not fall prey to the trap of oversimplification, looking for either China or the US to be the clear winner in their ongoing trade tensions. Both nations have the capacity to inflict significant economic damage upon the other, and both nations have significant vulnerabilities the other can exploit.

To what extent these latest trade maneuvers represent committed escalations of trade conflict as opposed to mere jockeying for better negotiating postures in preparation for new rounds of trade talks remains very much an open question. As we saw in the last round of escalation and negotiation, both China and the US have identifiable interests in de-escalating the conflict as quickly as possible. The longer any round of escalation continues, the worse the outcome for both countries, no matter which side is eventually seen as either “winning” or “losing”.

The best outcome for both China and the United States is a trade agreement that is fair to both countries. Both countries stand to benefit from a trade agreement that is a net positive to both countries, that stimulates economic growth for both countries.

In order to get to such an agreement, it is all but certain that China’s rare earths trade restrictions and the United States’ 100% tariffs on Chinese imports will not endure, but will be negotiated away. If that is the plan in both Beijing and Washington, this latest round of trade war tension will last only as long as it takes for both sides to find an achievable common ground, just as has been done before.

Will that take long? I hope not, but nobody knows that answer.

Good article, Peter. Linking it today @https://nothingnewunderthesun2016.com/

Another good one that I will be linking as well is by Nomi Prins - "🔥 Rare Earths War is Heating Up" - https://prinsights.substack.com/p/rare-earths-war-is-heating-up-bigtime

You and/or your readers may be interested in reading it also.

Rare earths were part of the reason Trump was interested in Greenland, correct?

Also, do you think the Chinese will press to ease US export restrictions on AI chips?