We do well to remember that, at the beginning of the year, the corporate media was convinced that the end of “Zero COVID” meant that the Chinese economy was set to undergo a major rebound, surging forward by as much as 5% in 2023 alone.

We do well also to remember that the “rebound” has never happened.

These points are relevant to understanding the import of the latest lifeline China is throwing to its Local Government Financing Vehicles in an effort to avoid a catastrophic debt default.

China’s biggest state banks are offering local government financing vehicles loans with ultra-long maturities and temporary interest relief to prevent a credit crunch amid growing tension in the $9 trillion debt market, according to people familiar with the matter.

Banks including Industrial & Commercial Bank of China Ltd. and China Construction Bank Corp. have started to ramp up loans that mature in 25 years, instead of the prevailing 10-year tenor for most corporate lending, to qualified LGFVs with high creditworthiness in recent months, said the people, asking not to be identified discussing a private matter.

Once again, China is turning to its old stimulus playbook and hoping it can borrow its way out of a crisis. Far from the economy experiencing a “rebound”, it is instead spiraling down ever deeper into recession and arguably deflation.

The immediate catalyst for the more generous loan terms is the sobering reality that China’s regional and municipal governments are heavily indebted, and many of them are already technically insolvent.

With the financing entities—notionally separate but implicitly backstopped by the regional governments—in debt to the tune of $9 Trillion, the number of provinces such as Guizhou to arrange last-minute debt restructuring agreements over their LGFV-incurred debts has been growing.

At the end of last year, a LGFV in China’s poor southwestern province of Guizhou announced that it reached an agreement with banks to extend loans of about $2.3 billion by 20 years. In addition, the company will make only interest payment in the first ten years and pay the principal via installments in the following decade.

While the proximate cause of the regional government debt woes is the collapse in land sales—long the “go-to” fund-raising option for regional governments—the debts themselves are a symptom of a much grimmer reality: the ongoing decline of China’s manufacturing and export economic mainstays.

Activity in China’s factory sector contracted for a third straight month in June, official data showed on Friday, signalling a patchy recovery in the world’s No 2 economy as global demand and raw material prices slumped.

Simply put, China is running out of ways to prop up its economy and postpone the economic day of reckoning.

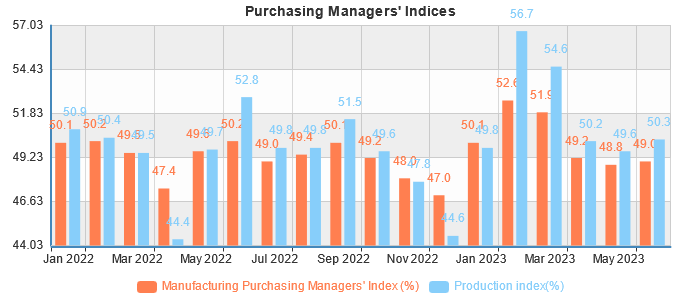

Despite a very brief surge during the first two months of this year, China’s official manufacturing Purchasing Manager Indices are printing lower now than they did under Zero COVID.

The degree to which the post-Zero COVID economy has underperformed the Zero COVID economy in China is easily seen when we compare the June manufacturing PMI numbers for the past three years.

At the most foundational level, there is simply no economic growth taking place in China.

With new orders declining, there is little prospect of economic growth in the near future.

Declining inventories do not add any confidence.

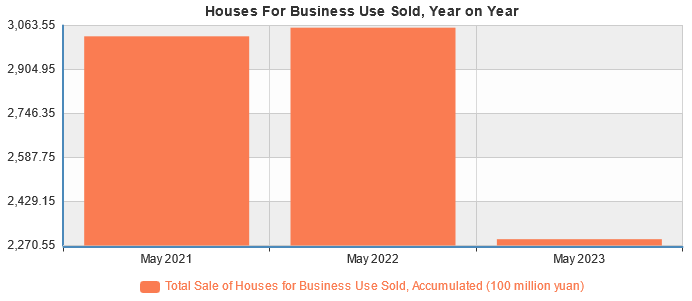

The real estate sector’s continuing collapse only makes matters worse. Year on year sales of houses for business use have plunged.

While the sale of residential buildings by May has increased over May of last year, those sales are a fraction of what they were by May of 2021.

Commercial real estate is likewise stuck in the doldrums.

Residential real estate has fared no better, with housing construction steadily decreasing.

Reversing the construction declines in housing without fresh stimulus is unlikely, as real estate developers are still stuck behind their own mountain of debt—a problem that took on new significance when it emerged that Shimao Group Holdings failed to place a new bond issuance of $1.8 Billion.

Defaulted developer Shimao Group Holdings Ltd. failed to find a buyer for a $1.8 billion project at a forced auction, even at a heavy discount. Sino-Ocean Group Holding Ltd. saw its bonds tumble on news that the state-backed builder told some creditors it’s been working with two major shareholders on its debt load.

They are the latest signs that China’s two-year real estate crisis is likely to remain one of the biggest drags on the world’s second-largest economy. A brief rebound after the nation scrapped Covid restrictions has quickly faded, with home sales resuming declines and property investment worsening, hurting markets ranging from iron ore to high-yield bonds.

If China’s developers are effectively shut out of global debt markets, they are effectively cut off from the funding they need even to just complete previously started housing projects, let alone commence and complete new ones. Not only does this ensure that the collapse of China’s real estate bubble is going to continue for a while yet, it also ensures that contagion from that collapse spreads to commodity markets while undermining the ability of Chinese firms broadly to access global debt markets.

China’s most essential economic sectors are all performing worse now that the Zero COVID protocols have been lifted than when the protocols were in full force. There is no way to interpret such data as signifying anything but economic contraction and decline. While the pace of the contraction is slow enough to make the term “collapse” still seem like hyberbole, the end result is the same: a shrunken dysfunctional Chinese economy with no immediate prospects for generating prosperity for anyone.

The massive indebtedness of China’s LGFV’s comes at a most inconvenient time: China’s traditional response to economic malaise has been massive spending driven by loans to the LGFVs. That is simply not an option for China this time around. The existing debt load is too great.

According to Bloomberg, without including bank loans to local government financing vehicles (LGFV), China’s total debt reached 279.7 percent of GDP in the first quarter of this year. This was an increase of 7.7 percentage points from the previous quarter, the biggest jump in three years. Goldman Sachs Group Inc. estimated that China’s total government debt is about $23 trillion if LGFVs are included. In 2022, S&P Global Ratings found that corporate debt in China reached nearly $29 trillion in the first quarter, the highest in the world and roughly equivalent to the size of the U.S. government’s total debt. Economist Ma Guonan has argued that China is “the most indebted emerging economy.”

With the LGFVs already having difficulty servicing existing debts, piling on additional debt becomes a recipe not just for economic crisis but economic catastrophe.

While debt can be an issue, previously many analysts assumed that Beijing would be more afraid of the potential social instability caused by a high unemployment rate. In fact, Liu He, former vice premier and one of China’s chief economic architects, apparently gave a clear answer a few years ago that the leverage issue, rather than unemployment, is more crucial for China. “Even if the economy is experiencing a significant downturn, employment can remain generally stable… However, the issue of leverage is different… Poor control over leverage will lead to a systemic financial crisis and negative economic growth, even causing ordinary people to lose their savings. This will be disastrous.”

Simply put, encouraging massive borrowing and stimulus spending by heavily indebted LGFVs carries an extremely high contagion risk, where a wave of LGFV defaults becomes a debt crisis for the Chinese banking system, sparking a replay of the 2008 Great Financial Crisis but with Chinese characteristics.

The usual economic palliative of fiscal stimulus is also blocked by the mundane reality of all debt: interest payments. No matter where the debt is carried, at the local, regional, or national level, so long as the debt is on someone’s books there is an interest expense which must be covered to avoid debt default. That interest expense is for China large and getting larger.

China’s provincial governments are facing unprecedented debt burdens following a collapse in land sales, a slowing economy and increased spending on Covid testing and lockdowns over the years.

Investors are becoming increasingly worried about the massive debt pile, which Goldman Sachs Group Inc. estimated this week has reached $23 trillion — or 126% of GDP — if off-budget borrowing by local governments are included. Curbing local debt risks was also highlighted by President Xi Jinping as a key challenge officials must tackle this year.

To reduce the massive debt and thus trim the interest expense, China’s regional and local governments must restructure and reform their bureaucracies—the sort of cost cutting measures normally associated with the austerity programs countries endure once they’ve defaulted on their debts as penance for daring to default. While such reform measures are hardly new even in China, laying off government workers and selling off government assets to generate cash for debt retirements will further suppress domestic demand, which is the polar opposite of what Beijing needs.

Rounding out the ways which China is trapped by prior economic policies is the reality that even monetary stimulus is likely not an option at this point, as it has already been deployed with minimal effect, according to the analysts at China Beige Book.

It suggests rate cuts by the People’s Bank of China in August may have had limited effect in spurring growth, and throws doubt on whether the latest round of rate cuts in mid-June will be effective.

“For months, analysts have pumped the idea that Beijing has little choice but big-bang monetary easing,” said Leland Miller, chief executive of China Beige Book. “The PBoC started its push some months ago, and the string didn’t move.”

Even the PBoC must adhere to basic principles of both physics and finance, the most basic of which is that you cannot push a string—a principle I’ve highlighted before in discussing the shortcomings of other central bank actions taken to goose other economies in the world.

Far from experiencing any sort of post-Zero COVID rebound, or staging any meaningful recovery at all, China’s economy is slowly but steadily spiraling down into not just deeper recession, but deflation—and Beijing has, by all outward appearances, run out of ways to halt the decline.

Without the availability of either fiscal or monetary stimulus to generate new momentum in either manufacturing or housing, China’s economic contraction is fated to continue until a bottom is finally reached, and a new natural equilibrium established. While such a bottoming out would have the decided benefit of giving China a solid foundation for economic growth going forward, it is an open question whether the economic decline necessary for achieving that solid foundation can be endured without catalyzing broader societal and political crises.

This is not idle speculation either, as economic stress was a major contributing factor in Xi Jinping’s abrupt decision last fall to terminate Zero COVID entirely.

Economic turmoil contributed to societal turmoil which threatened to produce political turmoil if something was not done to pacify an increasingly restive Chinese populace. Soothing the people this far has already forced Xi to reverse all his signature policies of recent years.

It is far too soon and far too presumptuous to say that China’s current economic woes mean the inevitable demise of the Chinese Communist Party. However, we have already seen the current economic decline lead to real declines in CCP influence and control—an authoritarian does not surrender his pet policies without surrendering a measure of his power and his clout as well. To extrapolate further waning of CCP power and influence from further economic decline is merely to extrapolate the recent past into the near future.

With no end yet in sight for China’s ongoing economic decline, how far can the CCP afford to fall without falling from power at last? Does this downward economic spiral mean the ending of the CCP will come not with a bang but a whimper? I suspect the answers to these questions will not be long in coming.

You are right. The CCP must continue, till it doesn't.

Donald Trump's election can't be allowed to go forward. This bears a poor prognosis for his future, but he has tagged his with the American people's.

The next year may prove critical, for us and the CCP. Or will it simply continue, many people are expecting something dramatic, but I caution them, it hasn't gotten this way by chance, this is being directed, and not by those fools at the WEF.