Financial markets the world over are highly optimistic over China’s coming economic “rebound”, now that it has put Zero COVID behind it once and for all.

China’s economy will expand by 5% in 2023, Fitch Ratings said in a revised forecast on Wednesday – an improved outlook from its previous 4.1% growth prediction made in December.

Fitch is not alone, with economists from the Wall Street Journal anticipating rising inflation in China, some of which will transmit around the world.

Economists expect China’s reopening to put pressure on prices at home and around the world this year, though the impact probably won’t be enough to prevent a gradual slowdown in global inflation as higher interest rates cool economic growth.

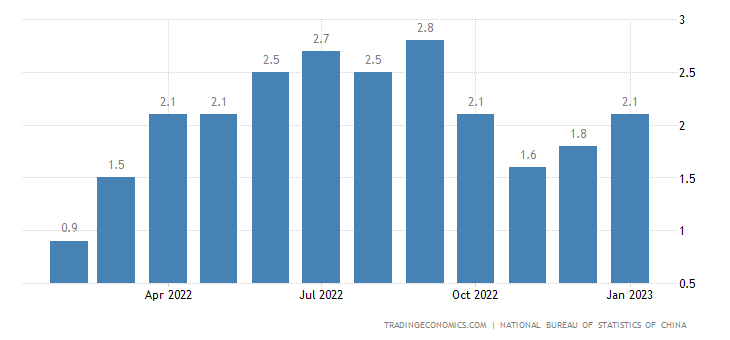

China’s consumer prices in January were up 2.1% from a year earlier, the country’s National Bureau of Statistics said Friday, accelerating from December’s 1.8% annual rate but slightly below the 2.2% expected by economists polled by The Wall Street Journal.

However, Zero COVID was ended at the beginning of last December. Are there any signs that the much-anticipated “rebound” has started?

To be sure, consumer price inflation did rise during January, from 1.8% year on year in December to 2.1% year on year in January.

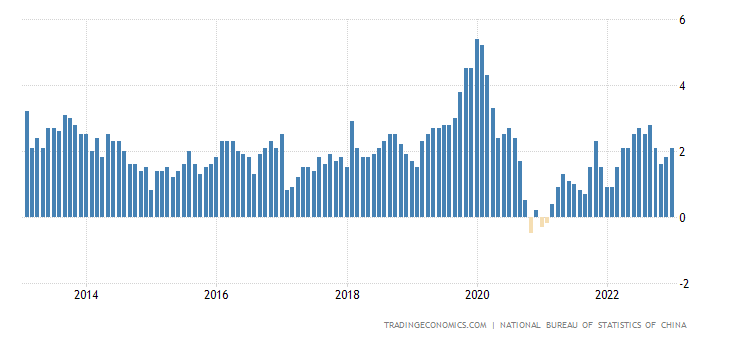

Most economists view rising inflation as a sign of increasing economic activity, which would make the inflation surge for China a good thing. However, it is important to note that consumer price inflation in China has historically oscillated around the 2% mark.

2.1% consumer price inflation, while a significant uptick from December, does not in and of itself reflect an extraordinary surge in consumer activity.

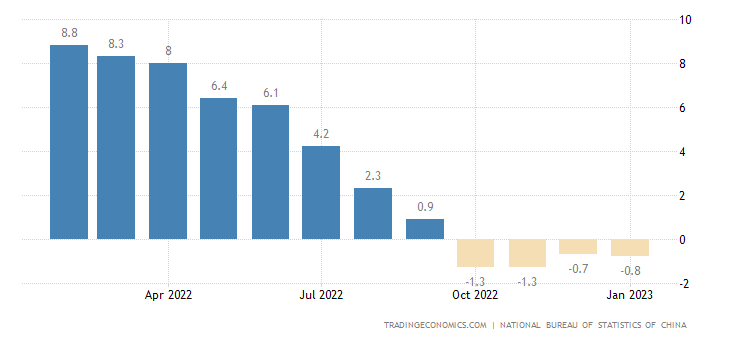

We should also note that, at the same time consumer price inflation rose to 2.1%, producer price inflation continued to fall, printing a -0.8% year on year for January, the fourth straight month of declining prices.

If producer price inflation precedes consumer price inflation, and Japan is showing producer price deflation, the projection would be that consumer prices are not likely to rise much in the near term.

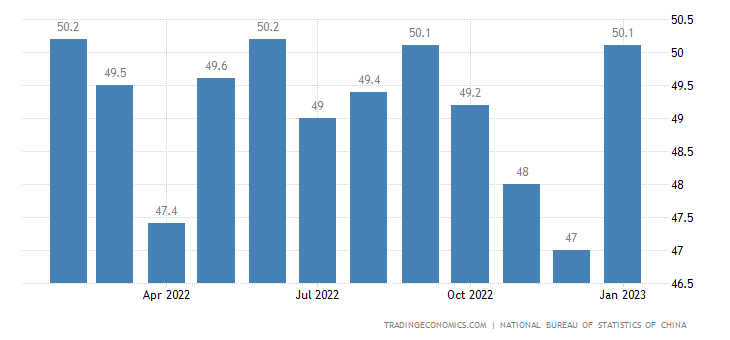

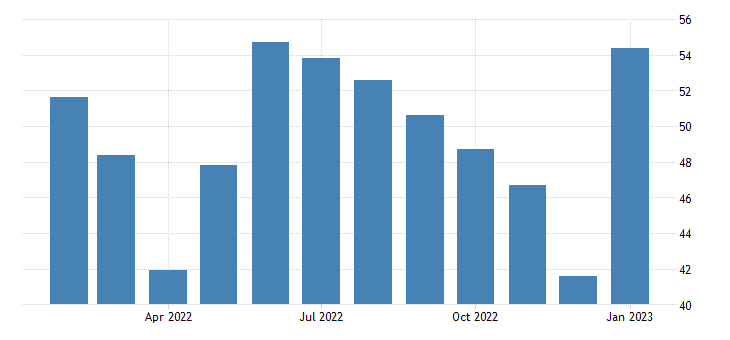

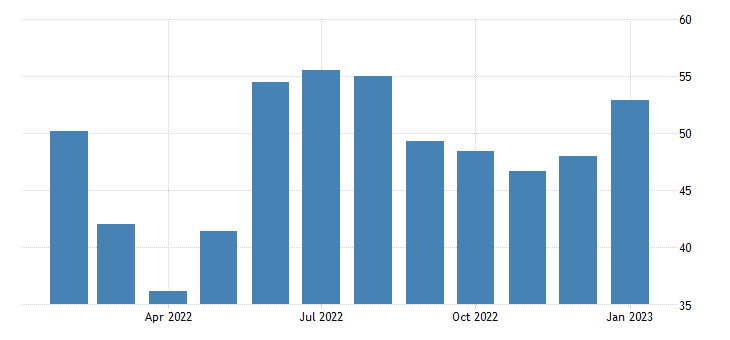

A much more positive sign is China’s official Manufacturing PMI. After spending the past three months deep in contraction territory, the Manufacturing PMI surged back into expansion for January.

The non-manufacturing PMI value was even better, rising up to 54.4 after having been at a glacial 41.6 in December.

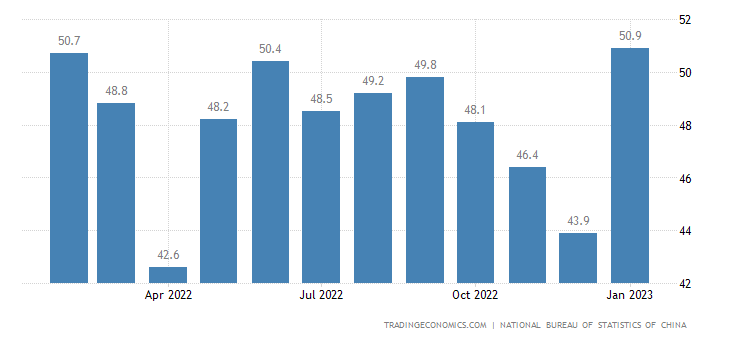

Another promising indicator is the rise in the new orders index, which also moved back into expansion at 50.9.

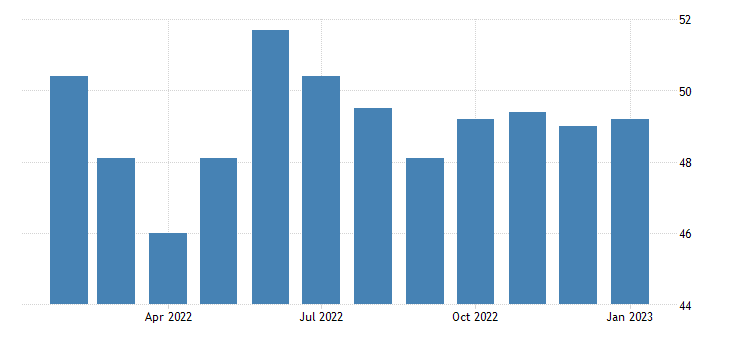

However, not every PMI indicator is as positive. Caixin’s separately calculated Manufacturing PMI still shows China’s manufacturing in contraction, ticking up slightly to 49.2.

Caixin did calculate services moving into expansion, with its China General Services PMI printing at 52.9.

Overall, the PMI indicators are showing rising economic activity in China.

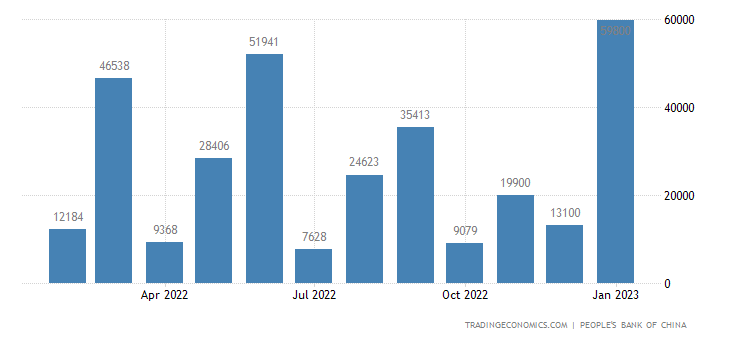

If China’s economy is showing signs of life, it is no doubt due largely to the banks pushing money out the door in the form of new loans to just about everyone. Total social financing skyrocketed to 5.98 Trillion Yuan in January, several orders of magnitude of increase from December’s 1.31 Trillion Yuan.

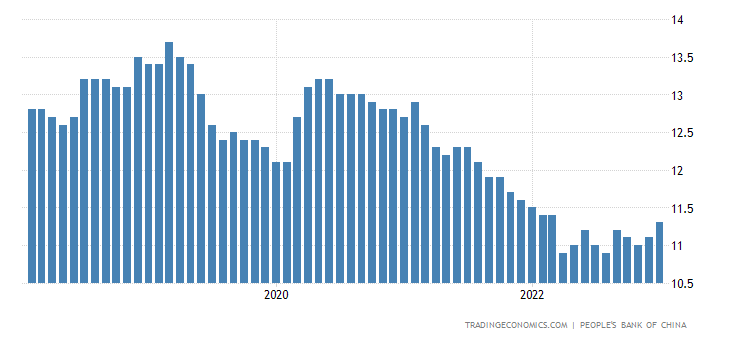

That flood of new loans pushed China’s outstanding loan growth to 11.3% year on year in January. While the rising loan growth is a sign of increasing economic activity, outstanding loan growth is till a fraction of what it has been in recent years.

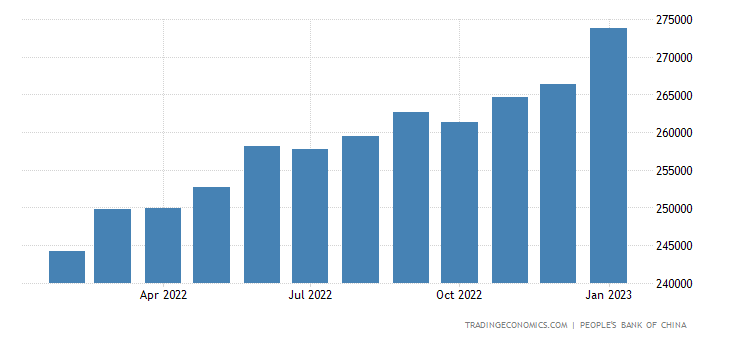

As might be expected with the rising loan activity, China’s M2 money supply metric also surged forward, rising 12.6% year on year to 273.81 Trillion yuan.

Certainly, the money is there for China to resume doing business.

While everything may be primed for China’s grand reopening, it is by no means certain that it is starting to happen as of yet.

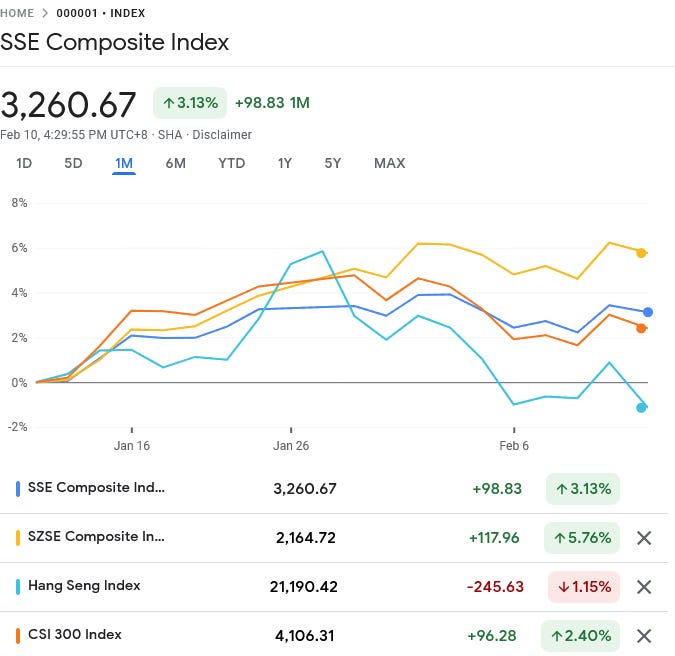

While China’s stock markets have had a positive start to 2023, the major indices have not risen all that much, and even declined during the last trading day.

The stock market increases have had their share of bumps so far this year.

Moreover, commodity prices have not risen, which one would expect if China’s factories were getting back into full swing.

Copper prices peaked in early January and have moved lower ever since.

Iron ore prices rose during January, but have since retreated.

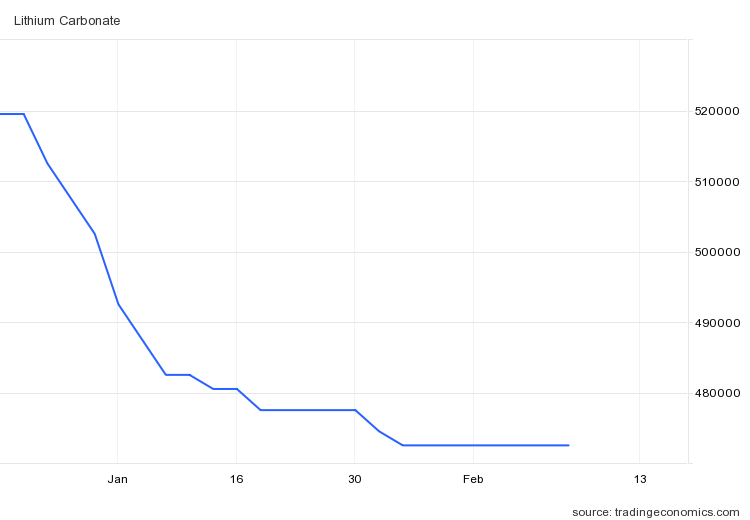

Lithium prices have been dropping since before the new year.

Metals in particular are the raw inputs for China’s factories. Increases in China’s factory activity should, at some point, be reflected in increased demand for these commodities, and thus higher prices for them.

At the present time, that rising demand does not appear to be there.

While the price of crude oil has been rising over the past few days, for most of January Brent crude was drifting somewhat lower.

If China’s economy were expanding at the pace forecast by most economists and China watchers, the price of oil would have been in a steady increase since December. While recent price rises arguably are indicative of a resurgent Chinese economy, those increases have only happened recently, indicating at a minimum that China’s return to economic expansion is still extremely recent.

After three years of Zero COVID economic suppression, there is almost sure to be some above above average growth now that Beijing has lifted its heavy hand off the economy. However, there are no economic magic wands, and Beijing has no capacity to wish the country back to robust economic growth.

It is not unreasonable to anticipate a significant economic recovery in China for 2023. However, the question as to whether that recovery is clearly and demonstrably under way must still be answered “not yet.” Recovery is still very much a future hope for China, not a present reality.

Good overview of the situation. The surge in the money supply is a big tipoff as to the scenario we can expect for the next few months. In standard Keynesian fashion the PBoC is clearly trying to jump-start economic activity by means of the printing press. This may work for some of the bigger businesses (e.g. the over-leveraged real estate developers), but they are not the real drivers of economic growth. After three years of enforced abstinence, most people are certainly eager to get back to work, but it will the micro-damage inflicted on SMEs will not be so easy to repair. A LOT of businesses went bankrupt and many of these will never resume business.

"If China’s economy is showing signs of life, it is no doubt due largely to the banks pushing money out the door in the form of new loans to just about everyone."

Any idea what China's total debt to GDP ratio is? By total, I mean government/public, corporate, as well as consumer, all together.