China’s economy is moving from contraction into slow, steady, collapse.

Despite all the optimistic projections about the “second half” of 2023, China’s economy has been getting gloomier and gloomier in the first half of 2023. The stagnant global economy has only made matters worse by helping to trigger steep plunge in exports during May.

China’s exports fell in May for the first time since February, adding to concerns that growth in the world’s second-largest economy could be faltering.

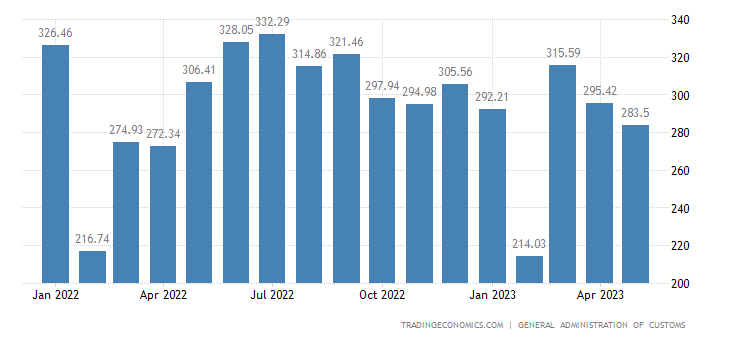

Exports fell 7.5% year-on-year to $283.5 billion, customs data showed Wednesday, far worse than the 0.4% decline predicted by a Reuters poll.

How bad is a 7.5% decline? It’s bad enough to put China’s exports at their second lowest level over the past twelve months. What is even worse, however, is that it is the continuation of a downward trend that actually began last July.

Even with a presumed resurgence during the first quarter after Zero COVID finally came to an end, China’s export levels never reached the levels it did while under Zero COVID.

That’s not a good sign. That’s a very, very, bad sign.

China’s imports have not been any better. While China’s import levels rose in May, the overall trend since last September is still down.

To add to the misery, many of China’s tech manufacturing companies are hurting. Last month Lenovo, the world’s largest PC manufacturer, reported a 75% drop in pre-tax profit during the first quarter of 2023.

The world's largest maker of PCs reported revenue of $12.635 billion for Q4 of its fiscal 2023 ended 31 March, down a brutal 24 percent year-on-year. Pre-tax profit was down 75 percent to $130 million on the back of workforce restructuring charges.

"By the end of this quarter or early next, the inventory digestion will come to an end so that the activation number and the shipment number will be more consistent," said Lenovo CEO Yanqing Yang.

The Intelligent Devices Group – the PC and smart gadget division – was most devastated by shifting buying patterns: revenue fell to $9.79 billion versus $14.69 billion a year earlier, a 33.3 percent decline, and one that may mark a bottoming out of shipments.

Lenovo was not alone. Industrial firms in China reported collapsing profits year on year in April—after suffering collapsing year on year profits in March as well.

In April alone, industrial firms posted a 18.2% drop in profit year-on-year, according to the NBS, which only occasionally gives monthly figures. Profits shrank 19.2% in March.

Overall, profits are down year on year 20.6% for the first four months of the year.

Let those numbers sink in for a moment. In April 2023, industrial profits were 18.2% below where they were during the month of Shanghai’s infamous Zero COVID lockdown from Hell.

April 2023 was a worse economic month for China than April 2022, which even last year was bad enough to confirm Xi Jinping was leading China over a Zero COVID cliff into economic disaster.

These are the months China was supposed to be “reopening”. Company income statements are saying that didn’t happen.

Amazingly, international observers and analysts continue to have a rosy outlook on China’s economic prospects.

According to China Daily, the OECD raised its economic growth projection on China to 5.4% for 2023.

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development rose the economic growth expectation on China again in a report released on June 7 local time to 5.4 percent this year and 5.1 percent next year, deeming that China's economic recovery fuels the global economy, China News Service reported Friday.

For its part, the World Bank projects China’s economy will grow 5.6% in 2023.

The World Bank predicted that China's economy will grow by 5.6 percent in 2023 and the OECD set this figure at 5.4 percent.

Spokesperson Wang Wenbin said that several international organizations and institutions such as the United Nations, the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund have recently raised their forecast for China's growth. Some of them even revised up the forecast more than once.

"It shows their confidence in China's economic prospect. The Chinese economy will continue to serve as an engine of growth and contribute to global economic recovery," he said.

How that is supposed to happen with collapsing exports, slumping imports, and collapsing corporate profits remains a mystery.

Rather, it is a far more reasonable expectation that China will have little to no economic growth in 2023, as the much ballyhooed rebound from ending Zero COVID has clearly passed and just as clearly was never as big as had been hoped.

Factory output and consumer spending revived after controls that cut off access to major cities for weeks at a time and blocked most international travel were lifted in December. But forecasters say the peak of that rebound probably has passed.

Retail spending is recovering more slowly than expected because jittery consumers worry about the economic outlook and possible job losses. A government survey in April found a record 1 in 5 young workers in cities were unemployed.

Factory activity is contracting and employers are cutting jobs after interest rate hikes to cool inflation in the United States and Europe depressed demand for Chinese exports.

China’s own statistics support this view, with virtually every index within the official Manufacturing PMI data showing a peak in February, and an overall decline since.

This view is confirmed by the reality of continuing producer price deflation within the Chinese economy, with the 4.6% decline in May exceeding the forecasted decline of 4.3%.

On the consumption side, month on month consumer price deflation continued for the fourth month in a row

Declining consumer prices month on month translated into an infinitesimal increase in consumer price inflation year on year of 0.2%.

Meanwhile, China’s Producer Price Indices have been contracting since last September.

With the data this dismal for the first third of the year in China, torrid GDP growth expectations for the rest of 2023 are simply not realistic.

Normally in such circumstances, China at this juncture would unleash a torrent of stimulus spending to goose the economy and artificially inflate its statistics. So far, however, China’s stimulus efforts have been muted, focusing almost entirely on reviving the housing sector.

Such a package is likely to include measures that will help developers improve their liquidity to restore market confidence while boosting demand, especially in China’s core cities, analysts said.

“Regulators will be more serious about rescuing the sector,” said Raymond Cheng, managing director of CGS-CIMB Securities. Lowering down payments from 30 per cent to 20 per cent, reducing mortgage rates and cancelling home purchase restrictions are among potential steps that could revive demand, he added.

There is a simple reason why the stimulus efforts this time are restrained: China is out of money. Specifically, the local governments which deliver most of the actual stimulus spending are already saddled with crushing debt burdens—to the tune of $23 Trillion.

Over the last two decades, local provincial governments in China began to build mega projects, specifically infrastructure, like roads, airports and ports. These projects were debt-financed and as long as the Chinese real estate markets were growing, revenue was getting generated. However, a real estate crisis beginning in 2021 led to a decline in revenue, leading to the current situation of unsustainable debt in the local provincial governments.

The Goldman Sachs Group, a global financial institution, estimates that the total Chinese government debt stands at $23 trillion. This includes debt accrued by hidden financial institutions and companies that provincial governments and cities have set up to fund development over the last two decades.

With nearly all Chinese provinces heavily indebted, rather than engage in further stimulus spending, they are being compelled to cut spending even on essential services just to be able to service their debt.

While the chance of a municipal default in China is relatively low given Beijing’s implicit guarantee on the debt, the bigger worry is that local governments will have to make painful spending cuts or divert money away from growth-boosting projects to continue repaying their debt. At stake for Xi is his ambition of doubling income levels by 2035 while reducing the gap between rich and poor, which is key for social stability as he seeks to rule the Communist Party for potentially the next decade or more.

Meanwhile, major Chinese developers such as Evergrande, China’s poster child for the bursting real estate bubble, are struggling with unpaid bills and debts. Evergrande’s unpaid bills have so far risen to around $127 BIllion.

China Evergrande Group said on Monday evening that its overdue debt, unpaid bills, and payments involved in lawsuits have piled up to nearly 900 billion yuan (US$127 billion), revealing the depth of the debt and legal woes the mainland Chinese developer faces amid its restructuring struggle.

The embattled developer said its overdue debts, excluding onshore and offshore bonds, amounted to around 272.5 billion yuan as of April, according to a Shenzhen Stock Exchange filing concerning its major litigation and failure to repay due debts. Its overdue commercial bills amounted to around 246 billion yuan.

Without fresh financing, China’s developers have little or no chance of getting their stalled projects back on track—essential for reviving once red hot real estate market. Yet the local government debt crisis that was apparent back in March has only gotten worse, with many cities already effectively bankrupt. Without local government spending, developers must rely on Beijing for support, which has been reluctant to do so.

Despite the rosy projections of the World Bank, the OECD, and the IMF, forex markets have recognized the growing debt and deflation crisis in China, and have treated the yuan accordingly.

Not only is the yuan been trending down against the US Dollar, it has actually fared even worse against the euro and the pound sterling.

Even the US banking and liquidity crisis earlier this year provided only minimal support for the yuan.

For all the talk late of “de-dollarization”, forex markets have made one thing perfectly clear: the yuan is not going to step up to be the global reserve currency any time soon.

Even the clearinghouse data from the international SWIFT system makes China’s weakness plain. While China is counted as the world’s number 2 economy, the euro, the pound sterling, and the Japanese yen are all used more often than the Chinese yuan (remninbi onshore).

Additionally, the dollar, the pound sterling, and the yen have all increased as a percentage of SWIFT transactions since April 2021. China managed to overtake the Canadian dollar, but the dollar and the pound especially gained ground on the yuan.

There is no number of optimistic outlooks that can overcome the reality of gloomy data and hard reality.

As I discussed last week, it is now painfully obvious that China has not had any actual “recovery” from Zero COVID, and just as painfully obvious that it is not going to have a recovery any time soon.

The painful reality of China’s economy is that it is now a spent force. With shrinking industrial profits and revenues, with crushing local government debt, and with a currency that has been getting steadily weaker over time, and against more than just the dollar, China’s economy has run out of steam as well as having run out of money.

China is sinking past the point of rescue, and sinking into an economic morass not just of recession, but of deflation and a lengthy period of economic stagnation.

What the world is seeing now is the beginning of China’s coming “lost decade.”

I’m trying to figure out the likely *sequence* of deflationary events in China and in the US. I would imagine that in China, the first part of the economy to show lowered asset values will be real estate, because that’s been in a bubble. After that, the command economy will disrupt normal supply-and-demand mechanisms because, as you’ve wisely pointed out, ‘you can’t push a string’. So their economy might descend in multiple ways, and maybe all at the same time. But in the US, I don’t know which prices will decline first. Maybe we need to have a recession for several quarters first, then layoffs, then rents coming down, then discretionary goods (clothing, sporting goods, etc.) lowering prices, with lower prices on food maybe not coming until a year after the first signs of deflation. During the Great Depression, the economy collapsed into 30%+ unemployment and deflation pretty quickly, but our economy is much different now. There’s unemployment insurance, welfare, bailouts, etc. So I don’t know what the sequence of events in the evolution of a deflationary era would look like now. I’ll bet you have the best insight into this of anyone, Cassandra Kust.

"When everything is heading south there can be no thought of economic recovery by definition."

-Peter Nayland Kust