China's Housing Crisis A Painful Lesson In The Laws Of Economics

The Reality Of Sunk Costs Has Yet To Fully Wash Over The CCP

China’s housing market in August entered its 12th consecutive month of price declines.

New-home prices in 70 cities, excluding state-subsidized housing, dropped 0.29% last month from July, when they fell 0.11%, National Bureau of Statistics figures showed.

This is the worst performance in housing since 2014-2015, when new home prices contracted for 13 months straight.

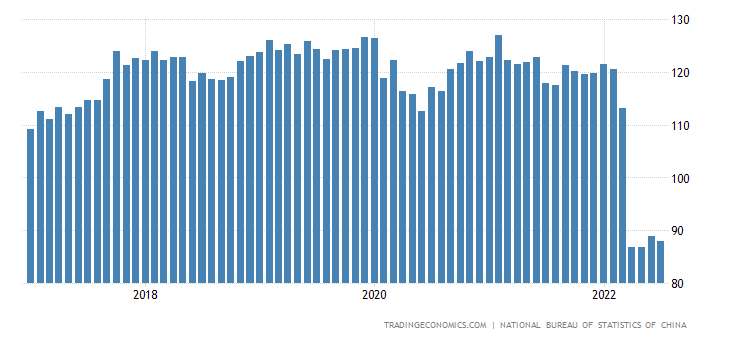

The housing slump is a driving force behind the recent collapse in consumer confidence, which in July dropped to 87.9 (anything below 100 indicates a pessimistic outlook on the future).

Thus China is being taught a brutal lesson in the iron inflexible nature of sunk costs—once you spend money, it’s gone, regardless of the consequences.

Housing Markets Are Collapsing

China’s residential real estate market is one economic sector where the term “collapse” well and truly applies across the board. Over the past couple of years, housing in China has gone from unstable to bad to worse—and there does not seem to be a bottom yet in sight.

The frenetic pace of house building used to be emblematic of China’s rise. Now confidence in the model has collapsed. Buyers are dropping out, borrowers are on mortgage strikes and developers face a liquidity squeeze. In July the value of new home sales fell by 29% compared with a year earlier. Country Garden, China’s biggest developer, has reported that its profits have collapsed and says the market “has slid rapidly into deep depression”.

The rotten foundations of China’s real estate sector were unintentionally revealed when Xi Jinping rolled out his “three red lines” to force property developers to de-leverage, and to end speculative housing purchases. Unfortunately for Xi, when the developers began to deleverage, they suddenly were left without the necessary funds to complete many of their housing projects—projects where the individual housing units had already been sold, with Chinese citizens taking out mortgages (and paying 100% of the purchase price in the process) on homes that had not yet been built.

The three red lines have deprived property firms of the cash they need to finish building flats that they had sold in advance. Delays in finishing past projects have in turn made it harder to sell new ones to disgusted buyers. Weak sales have worsened the cash crunch. And the absence of a coherent bankruptcy process has left firms like Evergrande in limbo.

While enforcing financial prudence among developers notionally seems like wise economic policy, in China it pulled back the curtain to reveal just how corrupt and mismanaged the entire property sector has been all along.

The result is a crunch. China’s developers need to sell homes long before they are built to generate liquidity. Last year they pre-sold 90% of homes. But without access to bonds and loans, as banks cut their exposure to the property sector, and with sales falling, the Ponzi-like nature of the property market has come into full view.

The crux of China’s housing crisis is fundamentally simple: Developers took 100% of the sale price for a new home before it was built, but spent that money on things other than building said home, relying on debt and new sales to keep construction going on previously sold homes.

Regardless of whether that money was spent wisely or foolishly, the money was spent. That money is gone—and the developers have no funds with which to complete homes already sold. Without fresh infusions of funds, those pre-sold homes will not be completed, and not even the omnipotent Chinese Communist Party has the power to command an alternative outcome.

To make the homebuyers whole and deliver the homes they have already purchased, someone is going to have to come up with a lot of money, and it won’t be the developers, because they’ve spent all their money.

China Discovers The Immutable Nature Of Sunk Costs

To appreciate the intractable nature of China’s housing crisis, one has to understand the nature of the term “sunk cost”1.

A sunk cost is a cost that has already occurred and cannot be recovered by any means. Sunk costs are independent of any event and should not be considered when making investment or project decisions. Only relevant costs (costs that relate to a specific decision and will change depending on that decision) should be considered when making such decisions.

The key words in this definition are “cannot be recovered”. In a very real sense, that describes the monies spent (and arguably mis-spent) by developers such as Evergrande, which is plodding through a tortured and complex bankruptcy. Regardless of where the money went, by and large it cannot be recovered and directed towards completing housing projects.

Even when Evergrande assets are seized, such as when its Hong Kong headquarters was reclaimed by a creditor, the assets are going to satisfy outstanding debts from defaulted bond issuances, not fund the construction costs of completing existing housing projects.

Even asset sales are going towards resolving Evergrande’s outstanding debts. Completing housing projects is not part of that.

Evergrande is believed to have amassed more than $300bn in liabilities and it struggling to pay its creditors via asset sales and debt restructuring.

Beijing has made some half-hearted efforts to address developers’ liquidity needs (which are simply funding needs—the cash to build has to come from somewhere), but they have been mostly muddled and have not thus far revitalized the sector. The most significant effort to date has been the somewhat diffident bond guarantee for China’s few healthy developers last month.

But the sales crisis now risks dragging down the good boys of the industry, too. The stocks and bonds of Chinese property developers rallied Tuesday following media reports that the government will guarantee new bond issues from some healthier private developers. Shares of the companies mentioned jumped: Longfor 12% and Country Garden 9%.

By and large, China has left the challenge of finishing housing projects to local governments, which have explored a variety of methods to address uncompleted housing developments.

Local governments, including the central province of Hubei, have taken steps to prop up the property market by setting up local bailout funds.

Zhengzhou was one of the first cities to do so, setting up a bailout fund worth 10 billion yuan ($1.43 billion) in July. The city government has proposed ways to several big developers to resolve the unfinished-home issue, including through loans, mergers and acquisitions, as well as turning the projects into subsidised rental housing, local media have reported.

In every instance, however, the bailout funds and other measures come down to the basic question of who pays to complete stalled housing construction. This much is certain: whoever pays the costs of completing unfinished housing projects, it won’t be the developers (if the developers had the money China wouldn’t have a housing crisis).

Local Governments Don’t Have The Money, Either

While local governments are tasked by Beijing with resolving the issue of stalled housing projects, the blunt reality is that local and provincial governments also do not have the money—they don’t have money, period.

Land sales have long been a key source of revenue for local governments, but the housing crisis has left developers unable and/or unwilling to buy new parcels of land. Increasingly, local governments have resorted to Local Government Financing Vehicles (LFGVs)—special purpose entities created to help municipalities fund various infrastructure and other projects while keeping the government balance sheet officially “clean”—to fill the revenue void.

Since last year, an increasing number of local governments have been trying to fill the hole in their budgets created by the collapse in the property market, which has left private developers unwilling or unable to buy land-use rights at auction. LGFVs have been prodded to step in to bid for the land, but it's left many already cash-strapped vehicles struggling to find the money because they are so heavily indebted.

Many LFGVs take on debt to purchase real estate (which frequently then just sits idle, with no plans for development or other use), in a perverse replay of the same fiscal incontinence that led property developers themselves into their current liquidity crisis. Similarly, just as developers are facing a liquidity crisis and unsustainable debt burdens, so too are the LFGVs, many of which are becoming delinquent on their debts.

At the end of August, 43 LGFVs -- including parent companies and subsidiaries -- had failed to redeem maturing commercial paper at least three times over the previous six months, analysts at Lianhe Credit Investment Consulting Co. Ltd., a consultancy, wrote in a note last week based on data from the Shanghai Commercial Paper Exchange. That's up from 27 at the end of July.

The LFGV credit crisis is made worse by the reality of collapsing tax revenues to provincial and municipal governments from corporations and businesses, and by the added financial burdens created either by the COVID-19 pandemic or the Zero COVID mass testing regimes and other protocols.

As a grim outlook looms for China’s economy in the face of multiple headwinds, local authorities already stretched thin by the seemingly never ending coronavirus outbreaks are struggling to keep their fiscal balance sheets clean. Revenues fell short of expenditure in all of mainland China’s 31 provinces, municipalities and autonomous regions in the first half of the year.

As China’s economic growth lags, authorities have been struggling with slashed revenues resulting from the property sector slump as well as tax rebates they need to pay as part of efforts to help virus-hit businesses.

They are also struggling under the burden of increased expenditures caused largely by coronavirus-related spending, including the costs of mass testing and social restrictions.

Virtually all of China’s provinces and municipalities experienced a revenue shortfall this year, and many have resorted artificially induced property sale revenue via their LFGVs to fill the widening finance gap. At the same time, the regular funding transfers from Beijing to local governments for the entire year has already been largely spent—and money spent is always money gone.

Meanwhile, this year’s central government transfer quota to local authorities has almost been used up, along with the quota for special purpose bonds dedicated to fund infrastructure projects, meaning Beijing has little more help to offer.

“Local governments should tighten their belts, put existing assets to better use, maintain a balance between revenue and expenditure, and guarantee fiscal spending to ensure people’s livelihoods,” Premier Li Keqiang said in a meeting last month.

Local governments that do not have the revenue streams to pay their existing debts incurred via the LFGVs also do not have the revenue streams to take on the financial burden of completing housing projects whose units have already been sold, meaning there is little or no additional revenue to allow anyone to recoup the cost of the additional financing.

Local governments, by and large, simply do not have the money to fund completion of stalled housing projects any more than debt-laden developers do.

Money Spent Is Money Gone

Whether the debt financing is being done by property developers or by the LFGVs, the Ponzi-like nature of real estate finance in China is still the same: debt is being raised to cover non-capital spending. While the developers took the revenue from pre-sales of homes and spent it on things other than construction of said pre-sold homes, relying on debt markets to generate the funding necessary to pay for that construction, LFGVs are now relying on debt markets to make up for revenue shortfalls for local governments. Servicing all this debt leaves little money left over for actually funding construction of pre-sold housing.

Money raised by property developers in China’s bond markets and spent on anything other than construction of pre-sold housing is money that can never be spent on construction of pre-sold housing. That money is gone.

Money raised by LFGVs and spent on anything other than construction of pre-sold housing is money that can never be spent on construction of pre-sold housing. That money is gone.

Yet money is what is needed. Without money to pay for construction costs, stalled housing projects cannot be completed. Without direct intervention from Beijing, it is uncertain where this money will be found.

What is certain is that, to a large degree, none of the entities tasked with finding that money—property developers and LFGVs alike—have the revenue streams or the fiscal purse strings to supply it. Resorting to China’s debt and bond markets merely reduces Xi Jinping’s “three red lines” regarding leverage to an anachronistic absurdity, and yet adding leverage is at all levels the only option available. The very thing which created the housing and debt crises is the only thing Chinese officials have available to stop them.

One of the iron laws governing economics everywhere is that money spent is money gone. No matter how necessary or justifiable an expenditure, once money is spent on any expenditure, it cannot then be spent again on any other expenditure. Money raised for real estate development and then spent on anything but real estate development can never be spent on real estate development. Not even an edict from Xi Jinping can alter this reality in the slightest degree.

That reality, in a nutshell, is the crux of China’s housing crisis. The challenge China faces now is how to replace that money without taking on further unsustainable and unamanageable debt burdens.

So far, neither the developers nor provincial and municipal governments have found the solution to that challenge.

CFI Team. Sunk Cost. 20 Feb. 2022, https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/knowledge/economics/sunk-cost/.

"Developers took 100% of the sale price for a new home before it was built, but spent that money on things other than building said home, relying on debt and new sales to keep construction going on previously sold homes."

They likely spent at least some of the money from new buyers building units for earlier buyers. This works pretty well as long as the number of new buyers keeps increasing.